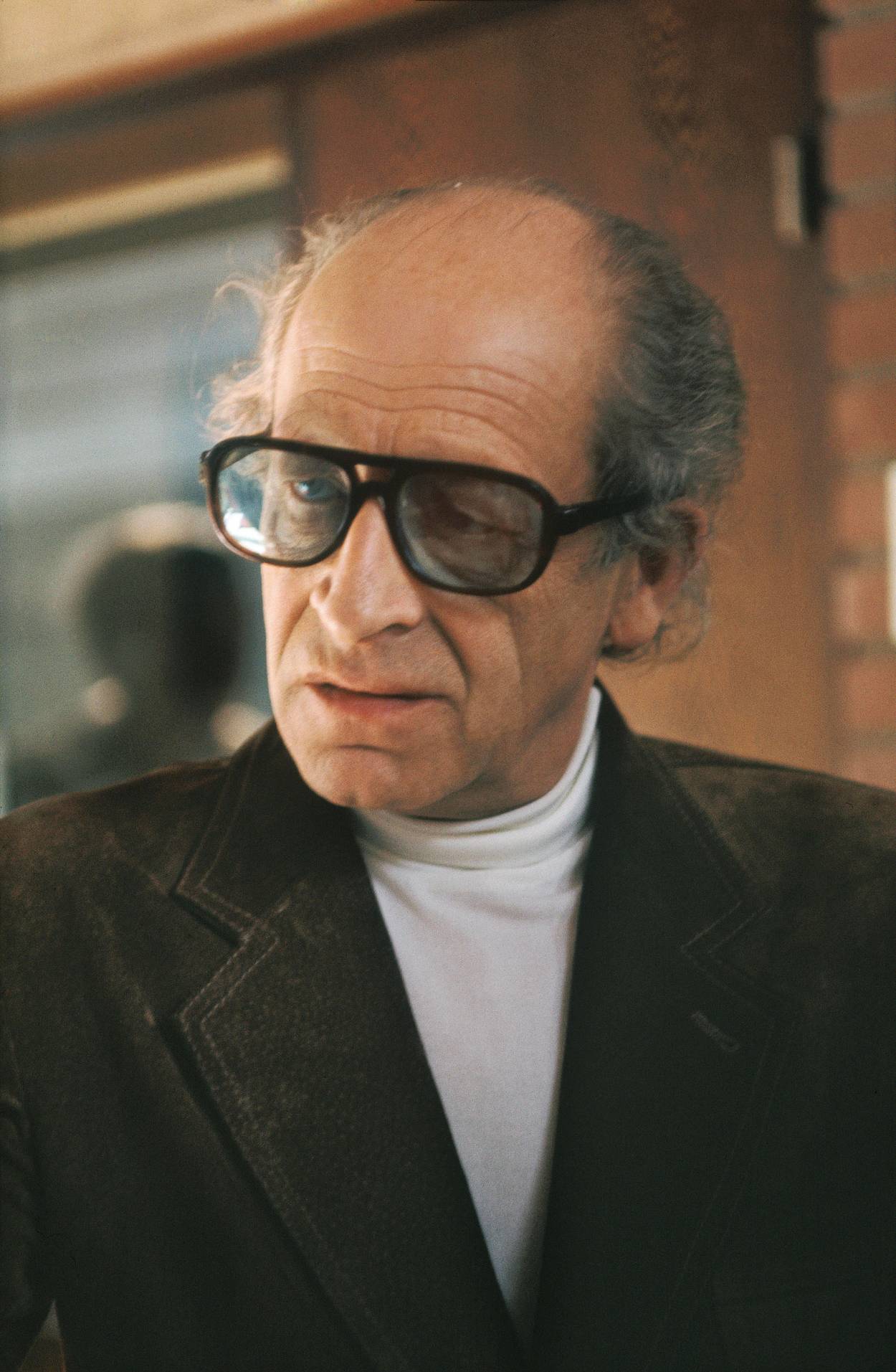

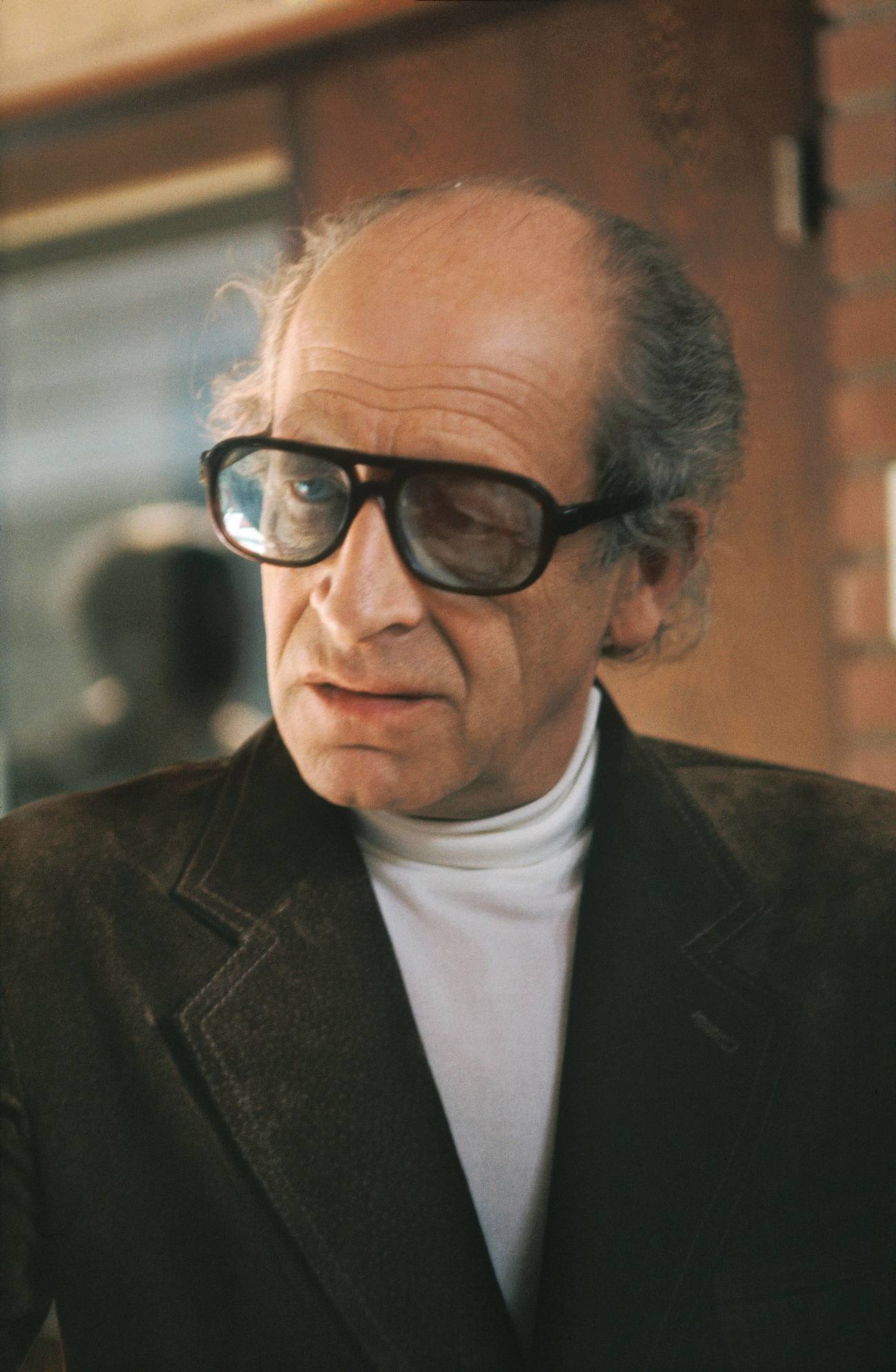

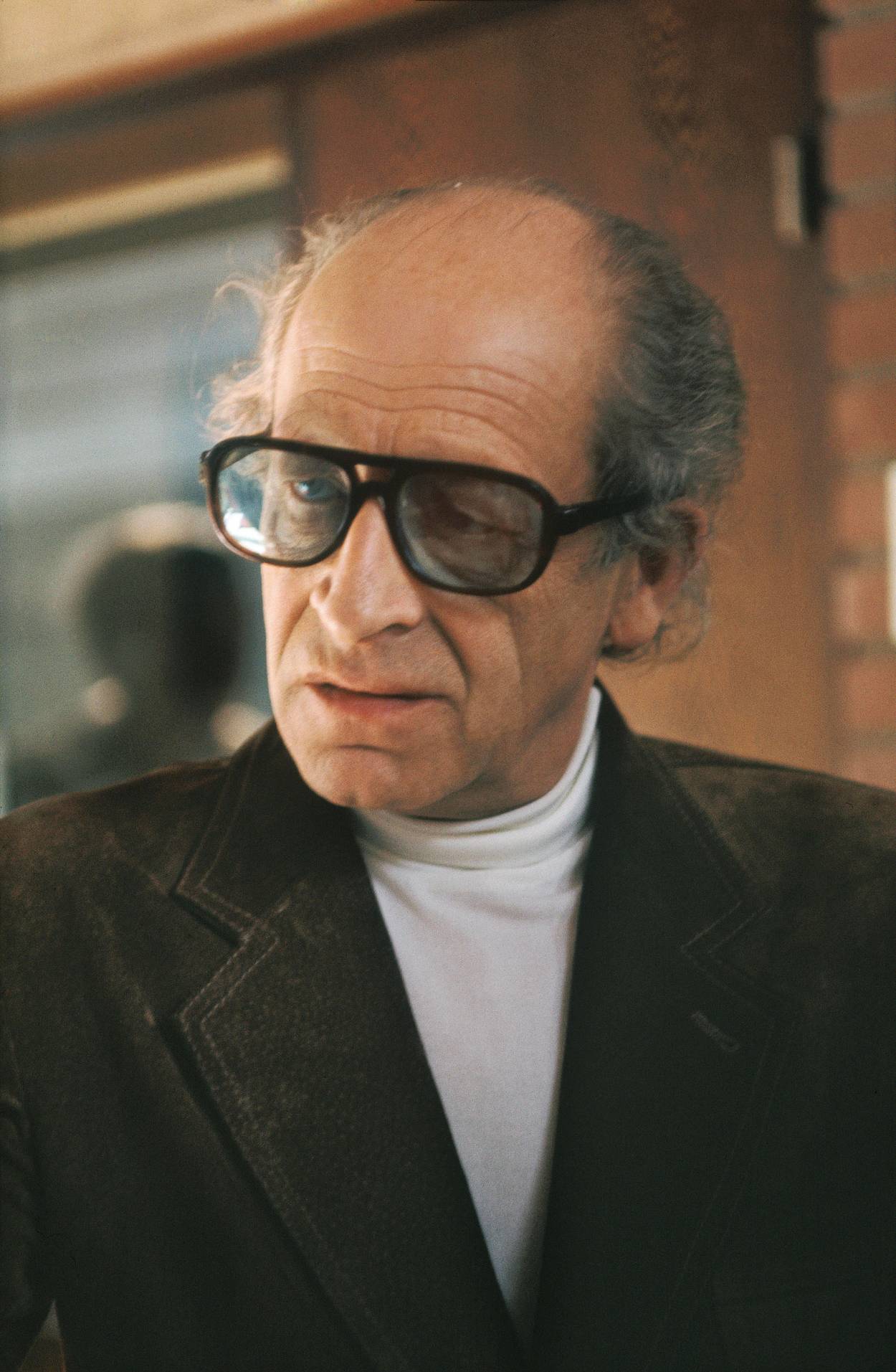

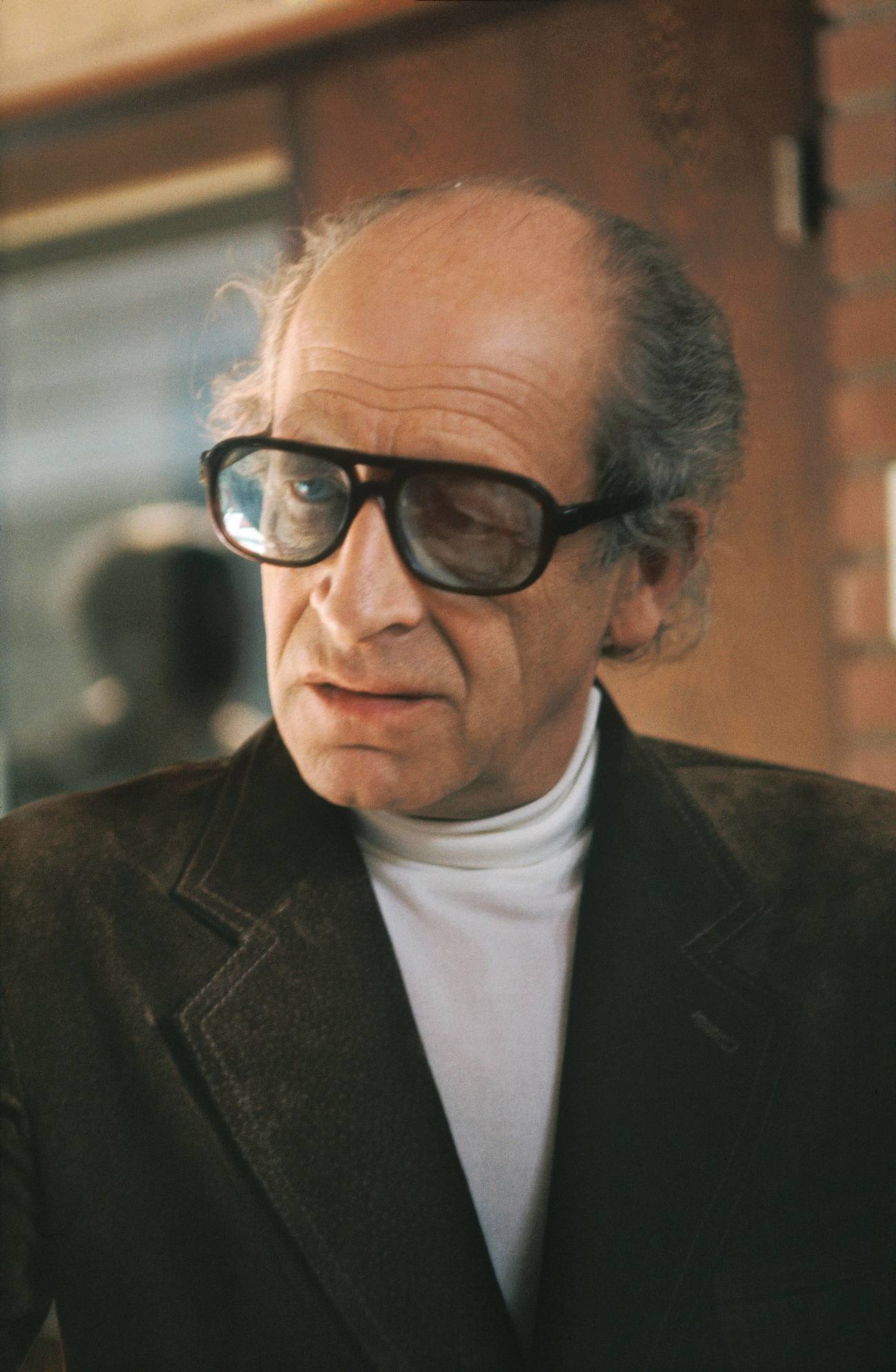

The Horrible and Enlightening Life of Jean Améry

In an age of easy antisemitism, the Austrian Jewish Holocaust survivor’s work remains bitter, resentful, and hauntingly pro-Zionist

Hans Mayer, a Jew from the Austrian countryside, was in love with the solitary woods, the streams, and the mountains of his native land. In 1934, when Hitler had been German chancellor for over a year and Catholic quasi-fascists controlled Austria, he wrote:

There are still tender, sensitive souls in the country ... comfort may still be found in the landscape and in solitude ... Let them be supported by a non-political conservatism. Let them remain quiet, clear, and pure, the quiet country people, for the stridency of those who would improve the world today suits them ill.

Mayer’s trust in “the quiet country people” was misplaced. The Nazis declared him not a native but a foreigner, and marked him for death. After surviving Auschwitz, he moved to Brussels. In 1955, protesting against his Germanic roots, he rearranged the letters of his name and became Jean Améry. (Amer means bitter in French.)

From the late ’60s on, Améry was a frequent presence in Germany’s press and was often on the radio, a living reminder of what so many Germans wanted to repress. Now Indiana University Press has issued Améry’s Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Left, which contains Améry’s polemic for Israel, and against the German left’s endorsement of Palestinian terror. These vital works continue to haunt us, as Améry would have wanted.

Améry spent his childhood in the Vorarlberg, in rural Austria. His Jewish father was killed on the front in World War I when he was 3. His half-Jewish mother was both “excessively affectionate and excessively authoritarian,” Améry remembered, and “if she happened to be furiously jealous, like a deceived lover, she would say bluntly that I would end up on the gallows.” By 8 Améry had read the plays of Schiller, and felt superior to his teachers. He adored going to church, especially on Easter Sunday, he recalled, “and yet I was vaguely aware that ‘in reality’ we were Jews.”

In the summer of 1932, Améry fell in love with a young woman from Graz, a redhead with a “snow-white complexion,” freckles, and “a tiny snub nose,” who wore the traditional Austrian dirndl. He discovered to his shock that she was not only Jewish but religious.

Améry had never thought much about Jewishness, least of all his own. Then came 1935. Améry said, “I read and interiorized the Nuremberg Laws forever. I became aware of my being a Jew.” Now, to say that he didn’t “feel Jewish” would merely be “private gameplaying,” a flimsy attempt to deny reality. He was a “catastrophe Jew,” forged by antisemitism.

During the March 1938 Anschluss, Améry bitterly remembered, Austria threw itself at Hitler “like a bitch in heat.” Jews were publicly tormented, forced to scrub the streets of Vienna. He was now married to Regine, the Jewish girl in the dirndl. A friend in the office of genealogy offered Améry an escape hatch: He could renounce his Jewish wife and swear that he was the product of his mother’s adultery with an Aryan. Instead Améry and Regine fled to Belgium, where he joined the resistance after Germany’s 1940 invasion. Arrested in July 1943, Améry told his wife that he would be back in half an hour. Instead he spent three months in the prison at Fort Breendonk, where he was tortured by the Gestapo.

On Jan. 15, 1944, Améry was deported from Belgium to Auschwitz. Of the 655 people on his transport, 417 were immediately gassed. Améry survived Auschwitz because German was his native language—in June he became a clerk at Buna-Monowitz, where Primo Levi also worked. Améry endured two other camps, Dora-Mittelbau and Bergen-Belsen. When he returned to Belgium, he learned that Regine was dead.

Améry made a living in postwar Brussels by writing books about jazz and American celebrities. Slowly, he started to turn toward his wartime suffering. In 1965 he wrote an essay for the German press about being tortured in Breendonk. At the Mind’s Limits was published the next year, containing the essay on torture as well as his account of Auschwitz.

In “On Torture,” Améry rather drily describes what he suffered under the Gestapo—he was hung from the ceiling, his arms dislocated from their sockets (“and now there was a cracking and splintering in my shoulders that my body has not forgotten to this hour”).

Torture, Améry says, was basic to the world of the Nazis, because in that world “man only exists by ruining the other person who stands before him.”

At the Mind’s Limits is titled in German Jenseits von Schuld und Sühne, “Beyond Guilt and Atonement,” a play on Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil. The book contains an essay in praise of ressentiment, the feeling that Nietzsche found poisonous, since it was the key to the “slave morality” he abhorred.

Nietzsche savages ressentiment, while Améry clings to it. Ressentiment, Améry writes, “nails every one of us onto the cross of his ruined past ... it desires two impossible things: regression into the past and nullification of what happened.” Améry knew that ressentiment “blocks the exit to the genuine human dimension, the future.” Yet he could not break away from it. In an essay on Améry, W.G Sebald remarked that “for the victims of persecution” like Améry, “the thread of chronological time is broken, background and foreground merge, the victim’s logical means of support in his existence are suspended.” Ressentiment is the height of illogic, since it both insists on and rebels against the one terrible fact, one’s “ruined past.”

Améry was a sensitive and ambivalent reader of Nietzsche, who, he said in another essay, “still excites us today ... but also irritates us.” Nietzsche’s “powerful, suggestive eloquence,” he argued,

constantly runs the risk of becoming mere loquaciousness; his inclination to megalomania; the intensity of his style, which always borders on a sometimes rather dubious lyricism; his polemical force, which all too easily obscures the actual meaning of the statement; the specifically Nietzschean misanthropy, which the psychologist may trace to a lack of love (since Nietzsche’s love for others went unrequited); the verbal excess that still today fascinates some thinkers, while others are struck with fear and trembling when they contemplate such intemperateness.

Améry’s characterizations of Nietzsche apply spectacularly well to himself. Like Nietzsche, Améry had polished Old World manners. One friend said he could picture him in a powdered wig, a man of the Enlightenment. But the charm was a cover for the loneliness that haunted Améry as it did Nietzsche. Like Nietzsche, Améry’s eloquence is constantly on the verge of loquaciousness. He is intemperate by nature, and he knows it.

Yet Nietzsche’s case was utterly different from Améry’s. Améry was sentenced to death because he was a Jew. Nietzsche never imagined such a fate, neither for the Jews nor for anyone else. In the camps, death was a banal fact, Améry insisted. There was no place for the yearning, alienated soul championed by German Romanticism.

A self-described man of the left, Améry was appalled that young Germans of the 1970s were taking sides with the Arab forces intent on erasing Israel’s Jews from the face of the Earth. In 1969 Améry wrote about the left’s “virtuous antisemitism,” cloaked (then as now) in the false postcolonial colors of anti-Zionism. “Antisemitism resides in anti-Israelism and anti-Zionism as the thunderstorm does in the cloud, and it has become respectable again,” he commented.

Améry described his own “virtually nonexistent,” yet all-important, relation to Israel thus:

I have never been there. I do not speak its language, how little I know of its culture borders on the embarrassing, and its religion is not mine. And yet, the existence of no other state means more to me.

Every Jew, Améry stressed, “lives off this achievement,” the existence of Israel. “It gives him a proper place in the world, whether he admits this to himself or not,” even if he thinks himself “wholly French or wholly American.” Three months before the Six-Day War, in June 1967, Améry said about himself, “Since there is talk of driving the Israelis into the sea, he is no longer a leftist intellectual but merely a Jew. For Auschwitz lies behind him, and the hoped-for Auschwitz II on the Mediterranean may well lie ahead ...”

Améry would visit Israel once, in 1976. In that year, he argued that the Arab-Israeli conflict “no longer bears the slightest resemblance to “normal” territorial disputes. It is pure Streicher. ... If Israel were destroyed, he asserted, “The world would again react as it did after 1933, when underpopulated states like Canada and Australia closed their doors to the Jews as if they were carriers of the plague.”

Améry’s reminder is timely these days. Anti-Zionism is once again acceptable cover for antisemitism. For strategic reasons, the Biden administration is again pursuing a deal with Iran that will leave that country on the brink of fielding nuclear weapons—making the threat to Israel’s existence greater than at any time since 1948.

In the early ’70s Améry plunged into writing Lefeu, or the Demolition, called an “essay-novel” because the author’s monologues are hard to tell apart from his main character’s. The cantankerous Lefeu is a hard-drinking, chain-smoking painter who refuses to move out of his Paris apartment building, which is going to be torn down. Out of sheer obstinacy, Lefeu, who lives on a shoestring, refuses to market his paintings. Eventually he remembers what he has for many years repressed: that his real name is Feuermann and that his parents were murdered by the Nazis. Lefeu decides to burn down the city of Paris, but instead settles for painting a canvas of Paris on fire. He then burns the painting and has a heart attack. “Survival [is] a contradiction [Widersinn],” he announces—but he survives.

Améry based Lefeu partly on Erich Schmid, a Jewish painter who, like Améry, escaped from Austria to Belgium in 1938, and whose family was killed in the camps. Like Schmid, Lefeu lives while so many others, including his parents, have died. Améry expresses his own survivor’s guilt through Lefeu. He must have felt that a natural death was not his proper fate. Four days after completing the manuscript of his novel, Améry attempted suicide.

Améry’s Lefeu encountered a formidable opponent, Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Like Améry, Reich-Ranicki was a Jew and a Holocaust survivor. He was also Germany’s most influential literary critic, someone who could make or destroy reputations.

In his review, which appeared in the FAZ in June 1974, Reich-Ranicki called Lefeu an “unintentional caricature and parody” of Améry’s essays. Améry was merely “letting himself go,” ranting at will, Reich-Ranicki said, so that he could “give in to his direct impulses and secret desires” and “follow his associations without remorse.” Améry was devastated, even though Alfred Andersch and Elias Canetti had high praise for the book.

In 1976 Améry published On Suicide, his most disturbing book, and his most self-contradictory. He argues against efforts to prevent suicide, which for him is a legitimate choice. He frequently uses the German term Freitod (free death) rather than Selbstmord (self-murder), the usual term for suicide. Killing oneself, he insists, is not just escape, but liberation. The illogic of suicide, like that of ressentiment, lures Améry, and his writing becomes excited, even manic.

Améry turns repeatedly to the misogynistic, self-hating Jew Otto Weininger, who killed himself at 23. In Weininger’s “brain, agitated to death,” Améry writes, “only woman is reflected again and again, the creature he despises yet for whom he is not able to master his desire.” Weininger, as he approaches his death, “constantly sees only the Jew, the most disgraceful and lowest of all creatures, the Jew that he himself is.”

In an essay from his last year of life, “My Jewishness,” Améry spoke ominously of walls closing in on him, the same image that he earlier applied to Weininger:

The four walls are moving in; the room is becoming smaller. My (involuntary) form of being a Jew without Jewishness (which, given my background and environment, I could acquire only at the price of turning my life into a lie) leads to the melancholia I endure every day. While experts would presumably classify it as “neurotic,” it strikes me as the only mood to which I am entitled.

Améry’s final book, Charles Bovary, Country Doctor, which appeared in 1978, hints at his own neurosis through his portrait of Flaubert’s character, who has been ruined forever by the disaster of Emma’s death. Another essay-novel, Charles Bovary is largely an attack on Flaubert for punishing his characters and himself so brutally. Mario Vargas Llosa argued that Flaubert created a “perpetual orgy” in the service of life and desire. By contrast, self-hatred motivates Améry’s Flaubert—“hatred of his class, of which, in his private life, he represents an ideal specimen.” Like Lefeu, Flaubert is a nihilist who cannot stand up to the world, so he substitutes his art for reality. “Defeat he experienced in his very depths,” Améry says about Flaubert. “The great doctor’s son was ‘just a fool, just an artist.’”

Améry wrote in On Suicide that killing oneself is a fact “much too horrible to be lamented.” The horror, he added, resides in a contradiction: The suicide seems to be saying I die, therefore I am. On Oct. 10, 1978, in a Salzburg hotel room, Améry took his own life. He left a farewell letter to his wife saying “I am on the way to freedom.” “I feel, like poor Charles, ‘terrible’ when I think of you, and am wretched,” Améry wrote. “But you have always understood me ...”

Ending his own existence was Améry’s most decisive blow against what the Nazis inflicted on him, since it released him from that trauma, but it was also a blow against himself. His tombstone in Vienna bears only his name, his dates of birth and death, and the number tattooed on his forearm—Auschwitz Nr.172364.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.