The House of Love and Prayer

The passion and death of Rabbi Yidel Glatt

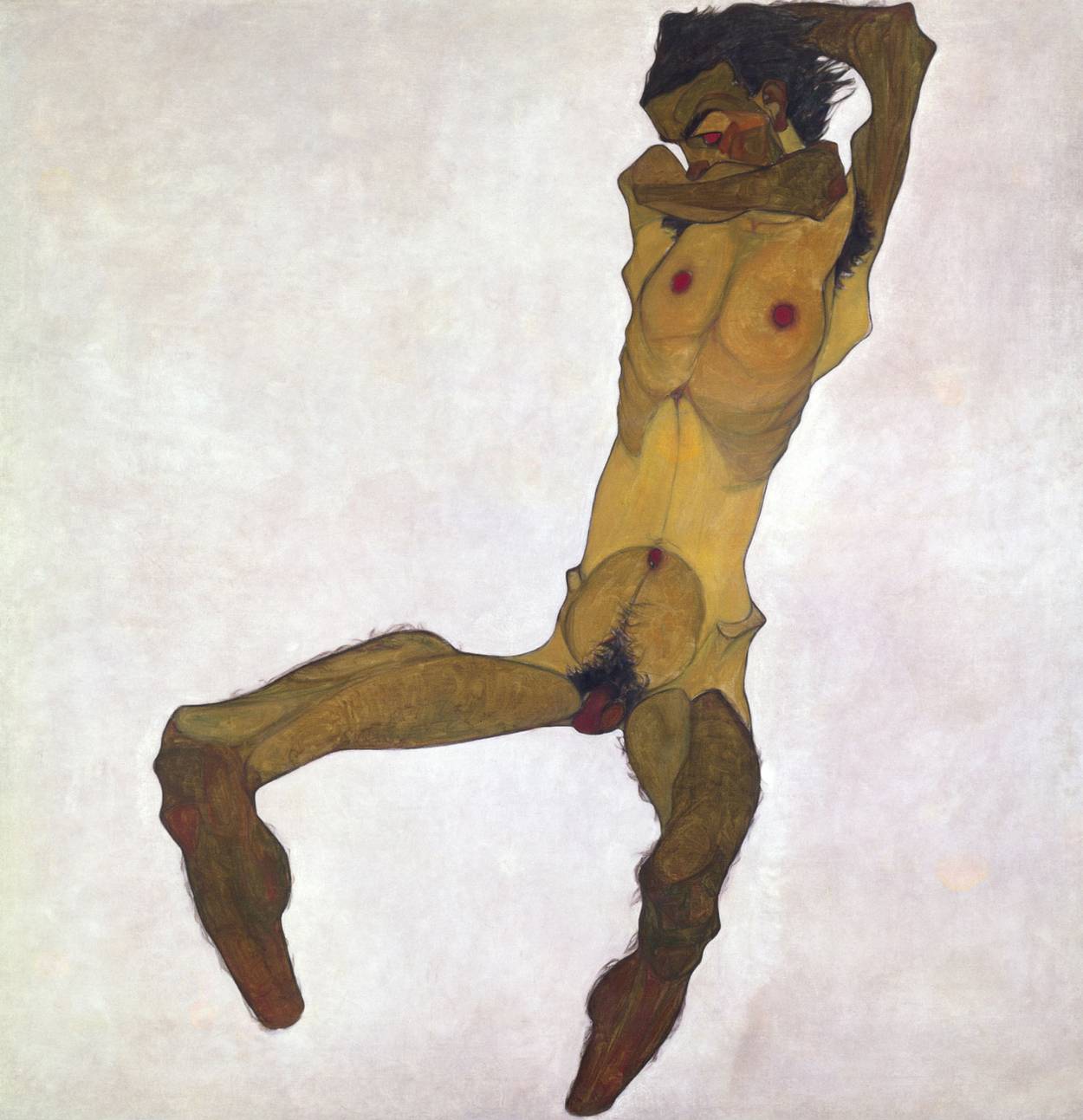

Private collection, Vienna via INTERFOTO/Alamy

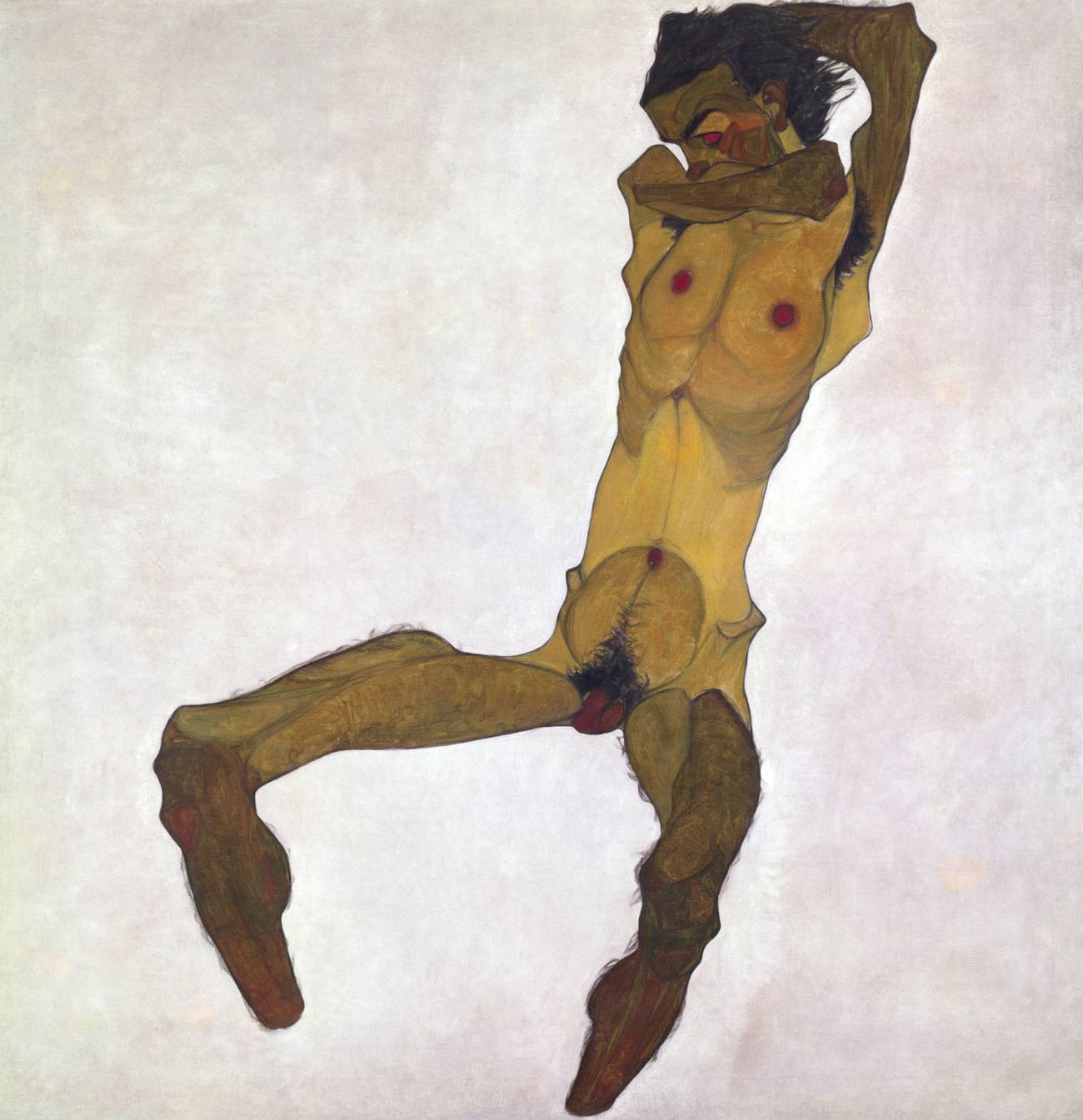

Private collection, Vienna via INTERFOTO/Alamy

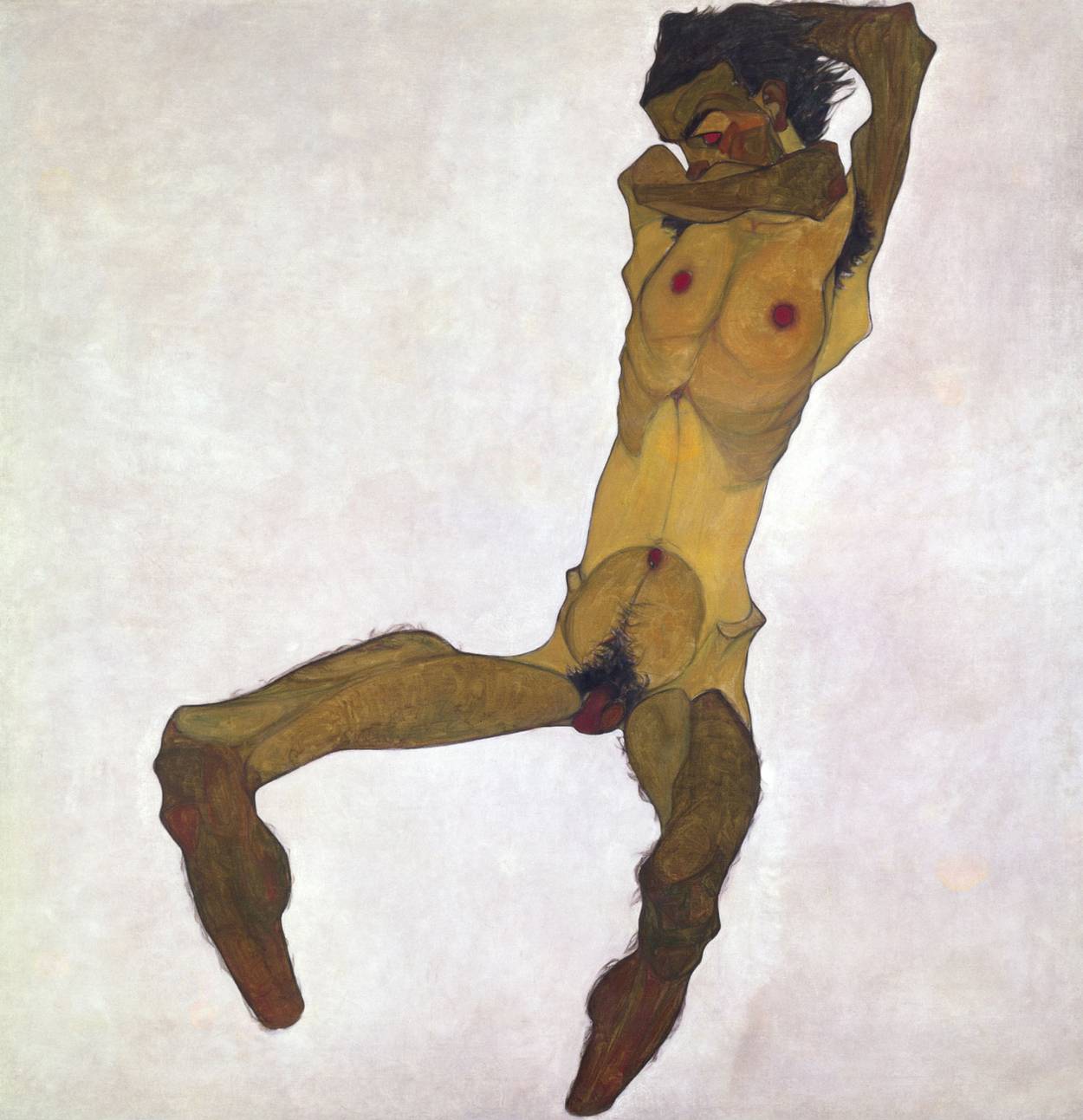

Private collection, Vienna via INTERFOTO/Alamy

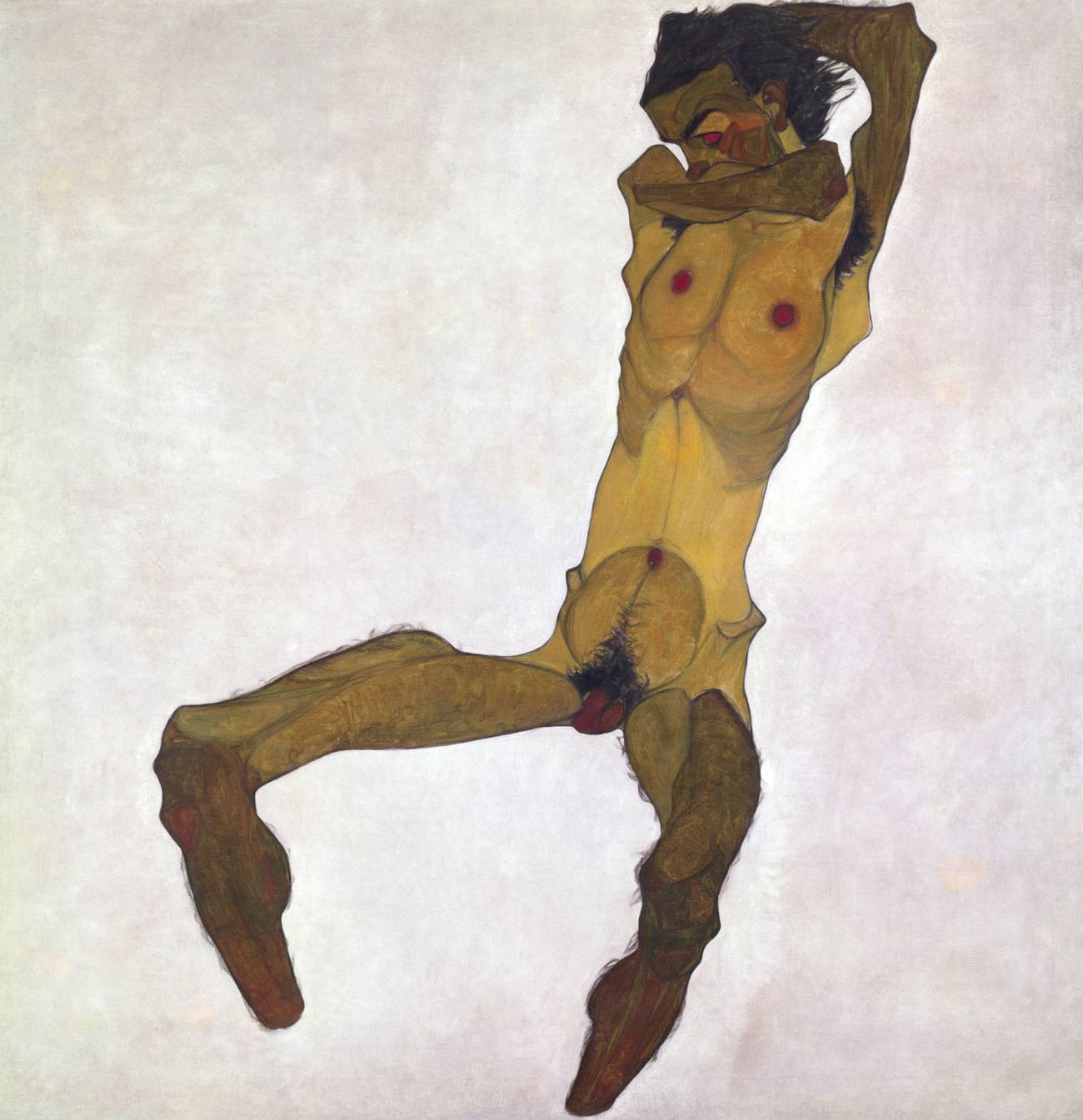

Private collection, Vienna via INTERFOTO/Alamy

Soon after he turned 40, Rabbi Yidel Glatt died of starvation, self-generated. Not that he had gone on a hunger strike, or had deliberately sought out death in some other way, God forbid. It simply came about naturally as an unintended consequence, so to speak, of his ultrarigid adherence to the laws of the Torah, many of which he rightly regarded as taking precedence over the grossness of inserting food into your mouth, especially in public, the unseemly wet chewing noises, the Adam’s apple bobbing obscenely, the whole mess flushed downward through the body’s sewer pipes to its profane end. All of this was a necessary function, of course, and scripturally required to sustain life, but nevertheless simple to expedite quickly and efficiently in most instances by eating the mandated piece of bread the size of an olive (albeit granted that olives can come in a range of sizes), and getting it over with as fast as physically possible. The blessing to be recited before ingesting the olive-sized morsel, on the other hand, and the grace afterward, demanded time and the purest concentration in order to achieve a mystical closeness with God—a closeness, as Rabbi Yidel taught his small but elite group of followers, that in our day and age, bereft as we are of the holy Temple where once we were able to offer our sacrifices directly, can only be accomplished through uncompromising submission to the laws of the Torah, and through undistracted focus on every syllable of prayer, even the tiniest prepositions and conjunctions, only deceptively inconsequential. From the literal to the spiritual, from the finite to the infinite, this was Rabbi Yidel’s mantra. His death set off anguished lamentations among his disciples, who strangely resembled him in their black kaftans and black hats with the extra wide brims from which, like Rabbi Yidel’s in his final year, a black veil fell like a shade to prevent their eyes from inadvertently snagging on something forbidden, as they walked wailing behind his earthly remains tightly wound like a scroll in a prayer shawl and carried aloft on a stretcher. They were all without exception strikingly tall and gaunt like their master, two dimensional, it was as if they were members of the same nearly extinct tribe with a specific body type and a limited life span. They resembled a procession of medieval monks, passing shadows, ghosts. And, indeed, by the turn of the millennium, every one of them had gone to join Rabbi Yidel in the next world, leaving behind numerous orphans, as the positive injunction to be fruitful and multiply is another animalistic bodily commandment that a man could also dispose of speedily, like eating.

Rabbi Yidel Glatt had appeared on the scene in the late ’60s of the last century, full-blown, as if not born of woman. No one knew who he was or where he came from. Later on, when anyone respectfully ventured to inquire, he invariably responded in the words of the sage, Akavyah son of Mahalalel, that he came from a putrid drop. He spoke with an accent of some sort, which grew more or less pronounced depending on the situation, and the needs and level transmitted by his interlocutor, to which he was so sensitively attuned. Most listeners identified this accent as a variation of British or colonial English, though others asserted that it contained the rich inflection and lilt of an educated Middle European, that English was after all his second language. There were even some who claimed to detect in his speech the subtle nuances of a Slav, plucked by the Soviets from the masses at a very early age for intensive training in American English toward a future as a high-powered interpreter or spy, it was conjectured, who, blown away by the 1967 Six-Day War and the discovery of his identity politics, went off course, and for some unfathomable reason was granted special permission as an early refusenik to emigrate, officially to the Holy Land, though as he often lamented, he had not yet achieved the merit to set foot on that blessed soil.

It was said, however, that as he had made his way westward across the American continent in the belly of the Greyhound toward a predetermined destination that had come to him in a vision, he had stopped off for a few months at a chicken farm in Toms River, New Jersey, owned and operated by Rabbi Sylvan Blech, who in addition to marketing his eggs and fowl on weekdays and to his pulpit gig on weekends, significantly increased his income during that turbulent period by training young men of draft age in the laws and techniques of ritual slaughter, after which he ordained them as rabbis by conferring upon them the certificate of smikha as he was entitled to do, which then allowed his protégés as official clergy or divinity to claim the 4-D deferment from military service and thereby avoid early death in the jungles of Vietnam. Those who subscribed to this narrative therefore logically concluded that Rabbi Yidel Glatt was actually an American, and his accent was nothing more than some kind of oratorical enchantment meant to draw in his listeners to the correct path, while the only definitive message others took from tales of his chicken farm sojourn in his wanderings through the wilderness of America was that, if true, it merely served to seal his extreme veganism, and perhaps also, in retrospect, to provide some insights into many of his other food issues which ultimately brought about his death.

It should be noted, though, that the Russia scenario acquired a fresh burst of credibility when further accounts of Rabbi Yidel’s epic crossing of the face of the American continent placed him for a period of time in Boulder, Colorado, where, according to reliable sources, he underwent the ritual of circumcision. With regard to these reports, the American-origins camp, while of course insisting on respecting Rabbi Yidel’s privacy, asserted that as the son of militantly secular pseudo-sophisticated Jewish intellectuals who disdained what they regarded to be a primitive and barbaric rite and believed they knew better than generations of their forebears, either he had not been circumcised at all, or due to the health benefits circumcision is alleged to possess, the procedure was performed on him by a medical provider soon after birth as nothing more than routine minor surgery, therefore making it necessary for Rabbi Yidel to reenact it as a brit milah by extracting the requisite drop of blood from the tip of his dedicated organ, collecting it on a white napkin of some sort, and displaying it to three witnesses. The Russia camp, for its part, hammered in the point that Jews from the rabidly anti-religion Soviet state were almost universally never circumcised, and though Rabbi Yidel Glatt might have been one of the earliest to be let out from that dark side, this fact was confirmed again and again over the next decades, as Russian Jews poured into the luminous free world lugging their musical instruments, including pianos. Thanks to the benevolent outreach of so many good and charitable organizations, thousands upon thousands of circumcisions were performed on these newcomers, who voluntarily came forward to offer themselves up on the altar of their recovered faith, even men with organs that had seen so much action in that sexually permissive, secular state, so much wear and tear over their average life expectancy span of 59 years. The model, after all, was Father Abraham, the first man to enter the covenant, 99 years old at the time of his brit, according to the Hebrew Bible.

Rabbi Yidel, for his part, was not yet 25, a thumb-sucker by comparison, but still he was fully entrenched in the tradition of Father Abraham, and like Father Abraham, he is said to have circumcised himself. There were only two other men present in the room, the mohel wielding the knife and a witness, a quorum of 10 circumcised males was not required for such late initiation into the covenant, so the report of what transpired within those four walls must have been leaked by one of those two, certainly not by Rabbi Yidel, who was meticulous in his personal reserve and discretion. And who could blame them? It must have been a gevaldig moment, tremendous, the need to tell somebody must have been intense. Suddenly, Rabbi Yidel lurched out of the chair of Elijah, properly zealous to perform the mitzvah, the sooner the better, as our sages encourage us. He grabbed the knife from the mohel’s hand and, without the benefit of any anesthetic other than the high of his personal fervor, made the cut himself before either of the two men realized what was happening or could do anything to intervene. Then he folded himself over at the waist like a pita, so flexible and supple was he thanks to the absence on his long, lean frame of even an ounce of extra flesh, placed his own mouth on the sacred crown of his covenant, and personally performed upon himself the mezizah, sucking up the blood. Afterward, he stretched out his hand, and the mohel, weeping loudly along with the witness at this overwhelming display of extraordinary righteous ardor, as if under a spell, docilely handed him the instruments to sew the sutures necessary on a mature organ. Rabbi Yidel did an excellent job, according to insider reports, it came out looking like a proper yarmulke with perfect stitching on the rim. When it was all done, he didn’t coddle himself for a minute, but shot up again out of Elijah’s chair, seized the hands of the mohel and the witness, and all three men danced around in a circle singing ecstatically the words intoned at the circumcision of an 8-day-old boy, May this little one become big, ya-ba-bum. It is also reported that before parting, they drank a celebratory glass of schnapps and ate a piece of matjes herring off a toothpick topped with a red cellophane frill, but this detail is very hard to believe as Rabbi Yidel was by then already 100% vegan.

Without sparing himself a minute, Rabbi Yidel accepted a ride with the mohel from Boulder to the Greyhound terminal in Denver, where he boarded the bus to San Francisco which was just about to pull out, but instead, thanks to personal divine intervention, paused, dipped courteously, opened its doors and welcomed him in. After two days in the belly of the dog on harrowing grinding roads, like the prophet Jonah tossed about in the belly of the great fish, he arrived limping in San Francisco and made his way to the legendary synagogue and hostel, the House of Love and Prayer, located in the orbit of the hippie Haight-Ashbury mecca, in order to carry out his mission of speaking his prophecy to its inmates that they must change their ways at once lest the whole edifice come tumbling down on their heads. There, still tender and aching but never complaining, the hand of God displayed itself to him once again by causing the door of the House of Love and Prayer to be opened by a complete stranger, Terry Birnbaum, known as Tahara. She had been waiting for him as he had been journeying toward her the whole time—she had prepared herself for his arrival by purifying herself in the ritual bath as her name implied, while, for his part, the mark he had made upon his own body was also meant for her. When they saw each other they both accepted this truth instantly. They were manifestly each other’s destiny, there was no other explanation and no escape, it was God’s will.

She was 18 years old, from a bagels-and-lox family on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, who had dropped out of NYU after only one month spent mostly sleeping all day and sitting all night stoned at the feet of Reb Lionel Ziprin, kabbalist and mystic, breathing in his poetry and songs in his mother’s Lower East Side apartment smelling of old age, where he presided. On her last night in Reb Lionel’s force field, he zoomed in on her perched there swaying on the carpet sucking on a joint and said as if in a prophetic trance, “Go west, young lady, there you will find what you are seeking.”

That, at least, was how she told the story to her 11 children and countless grandchildren years later. The next day she bundled some stuff in a madras cloth, tied it into a knot, slung it over her shoulder, and set out hitchhiking across the land. The many adventures she encountered as she made her way across the wild frontier toward the setting sun was something she would never detail to her children, it was enough for her to warn them that her own heart would crack in pieces if any of them tried a stunt like that and followed in her footsteps; she had been a tiny girl in those days, not even 5 feet tall and no more than 90 pounds, with long black hair parted in the middle flowing straight down her back and so fresh and pretty, if she must say so herself, no shoes on her feet and no money in her pocket, evil people took advantage, outlaws and bandits and desperados and other assorted bad guys, that was as much as she was willing to share. By the time she reached the House of Love and Prayer in San Francisco and the door was opened to her by its center of gravity, its guru, Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach himself, troubadour, minstrel, and pied piper, she was seriously damaged, polluted, filthy. “Oy, do you need a fixing,” Reb Shlomo said, after taking one look at her. He asked her name. “You no longer will be called Terry,” he intoned in his Teutonic singsong. “From this day forward, your name will be Tahara”—and he sent her off with one of the women to be ritually purified in the mikvah.

The next months she passed awaiting the arrival of Rabbi Yidel Glatt, though of course she understood this only retrospectively. She spent her days studying the healing arts, holistic medicine, acupuncture, wellness, massage, macrobiotic diets, organic farming, the power of crystals and stones and beads, mushrooms and cannabis, and so on, and at night she gathered with all the other lost souls at Reb Shlomo’s feet, getting higher and higher on his songs and streaming on his stories so that it was nothing less than an honor in those pre-dawn hours when the heart is clamped with dread to be the girl summoned to his chamber for warmth and further instruction. When she opened the door to Rabbi Yidel that day, he so tall and she so small, it was palpably and undeniably clear that she was his missing rib, she had been created to complete him. At last she understood the true meaning of the oracle pronounced by the holy fool, Reb Lionel, she knew why she had to come so far through such treacherous and alien territory, everything was clarified. A week after they met at its door, Tahara and Rabbi Yidel Glatt were married at the House of Love and Prayer in a wedding so fabulous it spilled out into the streets and lasted for three days and three nights of rejoicing, it was the mythic rave party that wouldn’t stop climaxing.

Those paying attention, however, could not help but notice that although the marriage ceremony itself took place under the stars in front of the House of Love and Prayer, Reb Shlomo’s turf, Reb Shlomo himself was not the one asked to officiate, nor was he included among the distinguished rabbinical personages called up to stand under the wedding canopy and offer one of the seven blessings, or, for that matter, was he given any honor at all. All of these honors were bestowed on rabbinical figures with credentials for the strictest observance and piety imported by Rabbi Yidel Glatt to San Francisco from Los Angeles, where contrary to popular preconceptions, such people truly could be found, they exist, they are not actors. Reb Shlomo and his inner circle of sinners were unqualified to perform his wedding, this was Rabbi Yidel’s absolute conviction, by no stretch did they live up to his standards. For the sake of drawing in all of those turned-off spoiled Jewish kids, and of capturing the souls of the whole congregation of Jewish losers, they took license to indulge all their evil inclinations, they were sinners in all their appetites, above the waist and below. Their participation in his marriage, other than as ordinary guests, would render it 100% pasul, unkosher, invalid, according to Rabbi Yidel Glatt.

Within an hour after he had sealed his betrothal with Tahara, following which they did not see each other again until their wedding itself, Rabbi Yidel Glatt stationed himself immediately inside the House of Love and Prayer, his back to the door, and he boomed out, “Don’t give me your New Ageism, your Interfaith Dialogue, your Jewish Renewal, your tikkun olam, your Holocaust idolatry, your self-indulgent practice, your lax observance, your counterculture, your HinJew, your JewBude, your two-state solution, your final solution, or whatever other solution your sick minds can cook up. If you don’t change your ways immediately, if not sooner, your whole House will come crashing down, the ravenous earth of this pagan city named for a gentile so-called saint will open up its ugly maw and swallow you up, like Korah and his gang of sinners.”

After that he shut down, entering into a fast of silence as well as a fast of eating for the entire week until his wedding day, parking himself those full seven days and nights like a Standing Baba on his spot right inside the House of Love and Prayer, a tall shockingly slender tree blackened by the fire of faith, the top of his black hat almost grazing the ceiling, his arms raised to the heavens as if in prayer like the arms of Moses our Teacher overlooking the plain of the wilderness below as the Jews battled the Amalekites. For seven days Rabbi Yidel Glatt stood there, transforming himself into an obstacle, an impediment, anyone who wanted to enter or leave had to factor him in, to take him into account, to consider him and what he stood for literally and figuratively in order to get around him and get past him. He broke his fast of what went into his mouth under the wedding canopy with a sip of the blessed wine, and of what came out of his mouth with the words he pronounced to Tahara without looking at her, behold you are consecrated to me, and so forth. On the seventh day after their wedding, her shaved head bound up in a turban woven from azure Indian silk shot through with gold thread, Tahara set out from the House of Love and Prayer, this time under the protection of the looming scythe-like figure of her husband, Rabbi Yidel Glatt, hitchhiking back eastward together across the fruited plain. By the time they reached Brooklyn, and settled in their tiny apartment with a fire escape over a ritual bath, prophetically called Mikvah Tahara, on 43rd Street in the ultrareligious Borough Park neighborhood, she was already noticeably pregnant with her first.

As the babies came, one after the other like clockwork, Rabbi Yidel Glatt, who earned a small income teaching in the apartment, was forced to move his classes out to the fire escape when the weather cooperated. There he could talk Torah in peace and quiet among the pots in which his wife Tahara grew her herbs and God alone knew what else, which, according to their landlady, Mrs. Bella Cohen, was also against city codes—to clutter the fire escape with junk—they were in violation on at least two counts, she would have to talk to them, give them a piece of her mind. Mrs. Cohen was completely unmoved by the fact that Rabbi Yidel Glatt refused to charge for his teachings in accordance with the injunction of the sages against using the Torah as an ax to chop with, meaning, bottom line, as he interpreted it, that it was forbidden to make money from the Torah. As far as Mrs. Cohen was concerned, business was business; whatever this meshuggeneh guru chose to do was his own private business, he personally did not need to eat at all it seemed, even if his children starved. Without a doubt his Hasidim left money for him somewhere on the fire escape when he held his classes up there, Mrs. Cohen figured, probably under the pots. The little wife would go out afterward to search, it was her job to hunt for the treasure, that way her holy husband’s hands stayed spotlessly clean, untainted, glatt kosher, ha ha, the money would just drop down like manna, like a miracle from heaven, the sin would not fall upon his head. Naturally his Hasidim gave him money, it goes without saying, Mrs. Cohen maintained, he was their rebbe, their master, that’s how it was done the world over, that’s how rebbes got their Cadillac limos and their first class plane tickets to Israel and their top-of-the-line sable Davy Crockett hats.

In cold weather, or in the pouring rain or snow, Rabbi Yidel delivered his teaching in the back room of Butch Pincus’ shop, known as TattJoos, on the fringe of the neighborhood. He had run into Butch in the lot on 18th Avenue where he and his Hasidim would gather each month to bless the new moon, the closest a person could come to the Divine presence, as Rabbi Yidel taught. Butch was a regular in the darkness of that lot, though it was known to be not such a safe place, filled with hungering souls prowling among the garbage and the rats, the used syringes and the used rubbers. One night, as Rabbi Yidel and his boys came out to greet the new moon, to sing directly into the ear of God under the open sky, pouring their hearts out like water in gratitude to Him for the light of this monthly renewal, Butch joined them in prayer, chanting flawlessly word for word from memory. It was clear that here among them was an authentic insider who had lapsed, strayed—the former BenZion Pincus, a descendant of certified rabbinical royalty no less, Rabbi Yidel soon discovered, who, as was well known in this Brooklyn ghetto, had gone seriously beyond the pale of settlement, straight into hell’s kitchen, bringing shame and grief to his illustrious family—in the excremental language of the written law, trafficking in the ka’ka business, this Pincus, tattoos, which as Rabbi Yidel knew, the Torah forbids 100%.

‘Don’t give me your New Ageism, your Interfaith Dialogue, your Jewish Renewal, your tikkun olam, your Holocaust idolatry, your self-indulgent practice, your lax observance, your counterculture, your HinJew, your JewBude, your two-state solution, your final solution, or whatever other solution your sick minds can cook up.’

Butch invited them into his parlor where he proceeded to spin his case for the legitimacy of tattooing despite the seemingly stringent prohibition against such forms of so-called self-mutilation as expounded in the book of Leviticus. “What is circumcising the flesh of your foreskin if not the number one tattoo in the history of mankind?” Butch insisted. “What does it mean to set a seal upon a heart? To place totafot between your eyes? Don’t give me that bullshit about the image of God, the sanctity of the body,” Butch declaimed. “Where was God with His sanctity when the murderers tattooed us in the death camps? Now by freely choosing to tattoo ourselves we turn anguish to joy, mourning to holiday, we adorn ourselves in the spirit of renewal, we resanctify our bodies, as we resanctify and renew our moon each month.” He, Butch Pincus, specialized in Jewish tattoos, he could show them some designs, they could choose if they were so inclined, or they could go creative and custom design their own, or they could just stick with the basic model already cut into their flesh, the mark of their covenant hanging there plain and forlorn between their legs if that was their preference, no pressure. Meanwhile, they were welcome to use the backroom of his tattoo parlor for their meetings when the weather was inclement, free of charge except for regular cleanings of the premises, maybe by one of their wives.

For this cleaning job, Tahara received no direct payment since it was effectively a swap, but here too, in Pincus’ shop, among the needles and inks and the sinister devices, she found in hidden places the bills that Rabbi Yidel’s followers left for their master so as not to sully him by depositing payment directly into his hands. Her other cleaning job, one that Mrs. Cohen had offered her in exchange for a reduction in the rent, was at the mikvah, to keep the place immaculate, wash it down every day—a sanitary, hygienic bathhouse was priority number one, absolutely nonnegotiable. For an added discount, Mrs. Cohen also called upon Tahara regularly to supervise the immersions of some of the ladies, in particular those who asked for her by name, more and more customers as time passed, she was still so tiny, though maybe not so svelte like she used to be due to all those babies, she was no threat at all, such a cute little roly-poly doll—the place, after all, was called Mikvah Tahara, it was only right, she was a terrific draw, very good for business and, bottom line, it was also a very good deal for that woman of valor, the Rebbetzin Tahara Glatt, whose rent bill in the end came down to bubkes, as Mrs. Cohen noted.

So it was not at all surprising that when Rabbi Yidel Glatt entered the mikvah for the last time on that warm spring night, he found his wife on duty. In truth, she was working there almost full time by then, while their eldest, Sora Malka, 15 years old already, looked after all the other children upstairs in the apartment. Though Rabbi Yidel knew very well that the nights were reserved for immersion by wives under the cover of darkness for the sake of privacy with regard to their monthly cycles and conjugal rhythms, the need to purge himself had suddenly gripped him overwhelmingly and would not let him pass. His black rubber glove, as if concealing a prosthesis, glistened under the newly blessed moon as he stretched out his hand to open the door with his personal key, his tense shallow breaths fluttered the veil rippling down from the halo of his black hat.

He encountered her instantly, in the waiting room, straightening out a pile of glossy magazines devoted to the Jewish woman and the Jewish home. She gazed at him, this was her husband, so tall and wasted, like a long dried-out reed that could snap at the slightest breath, and without uttering the words, her eyes spoke—What are you doing here? You know it’s ladies’ night. He thought maybe business was slow, he said, maybe there was a chance he could have a dunk. She had made a big pot of soup with kasha, strictly vegan naturally, she told him. Go upstairs and eat something, she said. He wasn’t hungry, he replied, he didn’t want to think about food, food interfered with his spiritual quest, it clogged his passageways, it came between him and God. Why was she bothering him with food at such a time?

Instead of answering, she rummaged in the pile of magazines, pulled one out, and held it up straight in front of his face, almost grazing his nose, she pushed it so aggressively close he could barely make out the words, the letters merged into a mushroom cloud. Anorexia Nervosa, he read finally the bold headline on its cover, An Epidemic in Our Community, and the background picture was of religious Jewish women of all ages, their faces blotted out for reasons of modesty, the outlines of their blurred bodies nevertheless visible even under their shapeless wardrobes, emaciated like classic concentration camp inmates, like scarecrows. It has nothing to do with God, she was telling him, bent on administering a therapeutic dose of tough love, so stop blaming God already. It’s an eating disorder, what you have, a body image thing, she said—it’s not just women’s troubles, she said, men get it too, like breast cancer.

He bowed his head and nodded. It was true, he was privileged to be suffering from women’s troubles, he granted her that, though he doubted she could penetrate the full depths of his holy affliction. In the most mystical of texts forbidden to almost all eyes, it was revealed that the messiah would be born not from a woman but from the bowels of a man, which despite the presence of waste matter was infinitely preferable to the blood-soaked womb and the polluted canal, even of a virgin. He was pregnant with the messiah. He longed to share this news with Tahara, but held back. Still, it remained his responsibility to limit the intake of food even more strictly, in order to keep his entrails as clean as possible, out of respect for the gestating deliverer. All this was information she was not yet spiritually ready to receive, he recognized. Instead, he ventured only to ask her to do him a kindness now, to enlarge the rear portion of his black trousers by sewing in a sac or a pouch of some sort, for the sake of comfort and modesty was what he told her, but in truth to catch the messiah, should he unexpectedly slip out, lest the holy redeemer fall to the ground and injure himself, God forbid, when he comes blinking into this world in a good hour.

It was as if his words entered the atmosphere and vaporized, they passed her by categorically, she blocked them so completely. “Why do you have that shmatteh flapping from your hat, covering up your whole face?” she only went on demanding. “And what’s this business now with the glove? Is this normal?” Stricken with pity for her limitations, Rabbi Yidel Glatt answered with head bowed, his voice barely audible, reminding her that Moses our Teacher also wore a veil, after sitting with God on the mountaintop for 40 days and 40 nights, eating no bread and drinking no water, God’s beams were imprinted on his face, the light was too much for ordinary mortals to bear.

He left the mikvah and climbed the stairs up to their apartment to complete the work of his dying, which took about a week. One by one, all of his systems and organs shut down from the consequences of starvation, until finally his heart gave out. Out of pity for the mother who bore him but whom she had never known, Tahara tended to him faithfully day and night throughout his dying—palliative care, home hospice she called it approvingly. He sat as if propped up in a wooden straight-backed chair, fully dressed like a Russian who having completed the preparations for a long journey, sits down and pauses to reflect before setting out, in his black kaftan and rope belt, his hat with the black veil firmly on his head and the black glove still sheathing his left hand. He refused to allow Tahara to remove any of his clothing, wrapping his withered arms around the jutting ribs of his hollow chest and shrieking horrifyingly whenever she ventured to loosen even a button. His followers, also in their long black kaftans and black hats with their veils attached, kept vigil in the hallway outside the apartment, on the stairs, and throughout the building including the mikvah, to the annoyance and frustration of Mrs. Bella Cohen—but unfortunately, there was nothing she could do about it, she was stuck. The man, after all, was dying.

The final agony lasted over two days of fierce suffering with no relief, until Rabbi Yidel Glatt’s soul visibly left his body through his mouth and out the open window in a long translucent rope, like intestines unraveling. It was only when the agony began to consume him that Tahara, with the help of her daughter Sora Malka, was able to lift him up out of his chair, he was so shrunken, practically weightless, as if he had been completely emptied out, and to lay him on his bed. Only then was Tahara able to take off his outer garments for the sake of easing his passage to the next world.

As he gasped for breath nonstop over the two days of the death rattle, hyperventilating desperately in shrill grating whistles and terrible dry cries scraped up from the depths of his cavernous being that shook the walls of their building and spilled out into the streets, Tahara sat at his side and kept watch. Now that his outer garments had been removed and he lay there like the excavated remains of a rare prehistoric creature, she could see at last how he had achieved the momentous permanent binding to the Divine for which he had so fervently longed and so obsessively striven all the years she had known him. Spiraling up his left arm and wrapped around his head were tattooed the black straps of a full set of phylacteries, the two black tefillin boxes with their parchment verses also visible gashed into his flesh, one on his inner arm pointing toward his heart, the other on top his head, totafot tattooed between his eyes. He had cut God into his own flesh, incised God as a permanent sign upon his own body, slashed God’s words into his heart and brain in uttermost subjection to the commandment. This was the reality to which Tahara now surrendered herself and accepted, but there were those outside their sphere who could never comprehend, she knew, it would look to them like transgression not longing, blasphemy not devotion, madness not passion. She made a mental note to herself that after it was all over, his followers, surely marked as he was by Pincus the tattoo artist, must be the ones designated to carry out the ritual known of all things as the tahara—they alone must be the ones to privately perform the purification of the body for burial, she would insist on that. Any other member of the community, the regulars of the holy burial society, simply wouldn’t get it, they would see what Rabbi Yidel had done to himself, misinterpret it as a form of idolatry, maybe even seek to block his interment in the cemetery, it would be an intolerable end to his story that she could never sit by and allow.

Thirty days after his passing, it began to be heard all around that Rabbi Yidel Glatt was, after all, not even Jewish. At first it seemed like nothing more than a spiteful rumor, but it didn’t fade away like an ordinary rumor. To the contrary, it grew and deepened and spread like a malignant plague—a Jew-impersonator in our midst of the most extreme and grotesque type, a caricature, a self-created stereotype, the worst kind of antisemite—so that the day soon arrived when the head of the board of the cemetery in which Rabbi Yidel Glatt was buried came to Tahara and requested that the body be removed with a full refund, not because of the tattoos, no, the rejection by a Jewish cemetery of a tattooed Jew was just an urban myth like crocodiles swimming among the turds in the sewers of New York City. It is simply because in accordance with our bylaws, the chairman of the board advised Tahara, non-Jews are forbidden an eternal resting place within the walls of our cemetery.

In the darkness of a moonless night, overseen by the widow, Rabbi Yidel Glatt’s followers went in and disinterred him. Those who glimpsed his remains asserted that he did not in death appear in any way different from how he had looked in life; it was the sign of a true holy man, they said. He was reburied elsewhere, to this day no one knows the exact spot, lest people come to worship at his gravesite, like Moses our Teacher who also wore a veil to shield onlookers from his radiance. In time, whether true or not, without benefit of any further proof, it became universally accepted as common knowledge—Rabbi Yidel Glatt was a gentile. For those for whom he had officiated as rabbi in such matters as conversion, marriage or divorce, the consequences were shattering, catastrophic, rendering all of his pastoral interventions invalid, all subsequent marriages and remarriages null and void, and all of the children from those marriages bastards and mongrels born in sin banned from admittance to the assembly of the Lord even to the 10th generation.

“The House of Love and Prayer” is the title story from Tova Reich’s new book, “The House of Love and Prayer and Other Stories,” recently published by Seven Stories Press.

Tova Reich is the author of The Jewish War, My Holocaust, One Hundred Philistine Foreskins, and other novels. Her most recent novel, Mother India, was a finalist in fiction for the 2018 National Jewish Book Award, and was longlisted for the South Asia Literature Prize.