If I Must Die …

On the intifada generation that sacrificed its poets

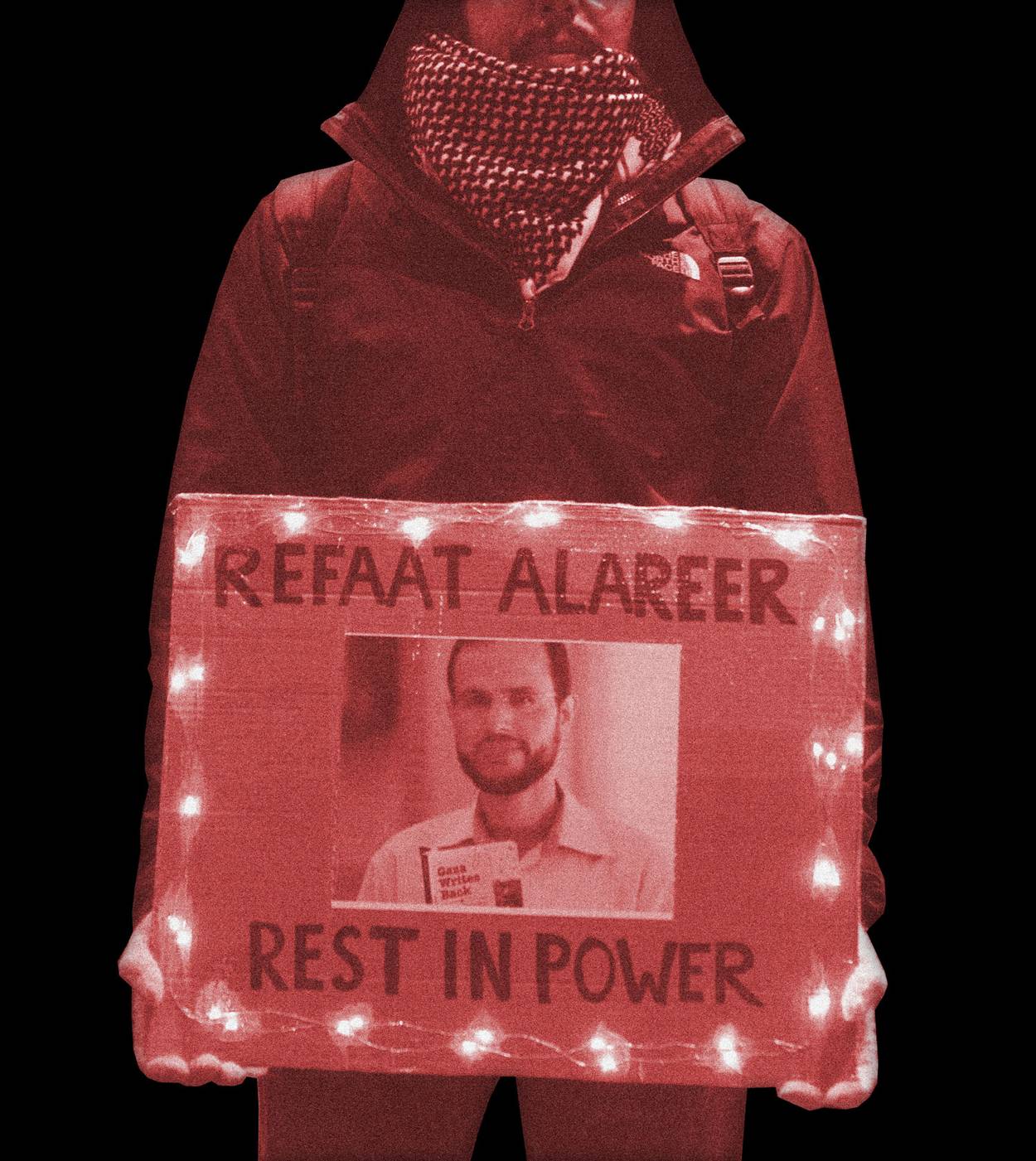

Original photo: Ying Tang/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Original photo: Ying Tang/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Original photo: Ying Tang/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Original photo: Ying Tang/NurPhoto via Getty Images

On Dec. 6, Refaat Alareer, a poet and professor of English at the Islamic University of Gaza, was killed in an Israeli airstrike in Gaza City. He was 44 years old.

Since his death, he has been eulogized the world over. The Scottish actor Brian Cox, who played Hermann Göring in Nuremberg (2001) and Logan Roy in Succession (2018-23), recorded a reading of Alareer’s final poem, “If I Must Die,” that has been viewed more than 13 million times.

As someone who has spent much of my academic and literary career thinking and writing about the destinies of poets in times of war, I am sensitive to accounts of poets’ death on battlefields and in besieged and bombed cities, and thus I was drawn to the reports of Alareer’s death, and his subsequent mourning by the international literary community—a valediction not forbidding Israel-hatred.

What kind of poet was Refaat Alareer?

Alareer was one of the best known representatives of Gazan authors born between the late 1970s and late 1990s, some but not all of them writing in English rather than Arabic, who distinguished themselves by depicting, in plain Homeric language, the existential conditions of writing hopefully against hope. In addition to Alareer, this coterie included Mosab Abu Toha, a favorite of American creative writing programs and literary hubs, who has not condemned Hamas genocidal atrocities even now that he has safely left Gaza for Egypt. Toha lamented Alareer’s death in a Facebook post: “This year, there are no strawberries, no books […], no English literature, no sea, no Refaat. Please Refaat, come back!”

Alareer’s work, tenderly keening at its best and banal and formulaic at its average, relies on strained cultural and historical transpositions. In “Drenched,” Alareer leans on the mythopoetics of the Hebrew Bible, specifically on Psalm 137 (“By the rivers of Babylon …”), to conjure up a climate of internal displacement. In this inapt analogy, the Gazans become the Jews of Babylonian captivity, and today’s Israelis the new Edomites. By implication, Alareer hopes that the poetry he composes is seen as running counter to the stark refusal of ancient Israelites to perform before their captors in Psalm 137. This is the opening of Alareer’s poem:

On the shores of the Mediterranean,

I saw humanity drenched in salt,

Face down,

Dead,

Eyes gouged,

Hands up to the sky, praying,

Or trembling in fear.

I could not tell.

The sea, harsher than the heart of an Arab,

Dances,

Soaked with blood.

Only the pebbles wept.

Only the pebbles.

“All the perfumes of Arabia will not”

grace the rot

Israel breeds.

Toward the end, Alareer looks to Jerusalem as he plants, in the image of weeping pebbles, a reference to an episode in Luke 19, where Jesus and his disciples walk down the Mount of Olives to be confronted by the Pharisees:

And some of the Pharisees from among the multitude said unto him, Master, rebuke thy disciples.

And he answered and said unto them, I tell you that, if these should hold their peace, the stones would immediately cry out (KJV, Luke 19: 39-40).

That this poem is positioned to speak to a broad audience of Anglo-American readers becomes clear in the antepenultimate verse, a direct quote from Macbeth, where in Act V, Scene 1, Lady Macbeth pronounces: “Here’s the smell of the blood still: all the / perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little / hand. Oh, oh, oh!” In this forced parallel, is Lady Macbeth supposed to be Israel, and the residents of Gaza, the murdered King Duncan? Or is the quote from Shakespeare supposed to validate the poet’s roots in an ancient high culture of Arabia?

This poetry forges its meaning and significance by appropriating various other pasts, and most predictably by fashioning its existential condition as a historical reincarnation of Jewish suffering and victimhood, from the biblical times to World War II and the Shoah. Consider the opening of “I Am You,” a longer poem by Alareer, which was recited at vigils by the same young Americans who refer to Israel as an “apartheid” and “settler-colonialist” state and chant for “revolution, intifada”:

Two steps: one, two.

Look in the mirror:

The horror, the horror!

The butt of your M-16 on my cheekbone

The yellow patch it left

The bullet-shaped scar expanding

Like a swastika,

Snaking across my face,

The heartache flowing

Out of my eyes dripping

Out of my nostrils piercing

My ears flooding

The place.

Like it did to you

70 years ago

Or so. […]

Very much in the tradition of Soviet anti-Zionist propaganda (which is presently at the service of anti-Zionist groups from Jewish Voice for Peace to Students for Justice in Palestine), Alareer portrays Israel as a new Nazi state, and Gazans as that state’s victims. The poem’s rhetorical structure makes today’s Jews, in Israel and in diasporic communities, the “you”—the addressee of the poem.

Could the “you” be aimed more directly at today’s Jewish poets or dialogue with Jewish poets who lived and died during World War II and the Shoah? In some of its Jewish readers, Alareer’s poems may provoke a reaction of shame. To this reader, his poems mainly reveal the crooked seams of their construction.

Alareer’s work, tenderly keening at its best and banal and formulaic at its average, relies on strained cultural and historical transpositions.

In November 2021, Patrick Kingsley profiled Alareer for The New York Times. Alareer, whose own doctorate dealt with John Donne, was praised in the article for teaching modern Israeli Hebrew poets like Yehuda Amichai and for emphasizing the Jewishness of Shylock (of The Merchant of Venice) and Fagin (of Oliver Twist). The profile was later appended with an editorial note, the Times admitting that their complimentary portrayal of the poet was at odds with some statements Alareer made in a taped lecture in 2019. “[H]e called [Yehuda Amichai’s] poem ‘horrible’ and ‘dangerous,’” the Times stated, “saying that although it was aesthetically beautiful, it ‘brainwashes’ readers by presenting the Israelis ‘as innocent.’ He also discussed a second Israeli poem, by Tuvya Ruebner, which he called ‘dangerous,’ adding ‘this kind of poetry is in part to blame for the ethnic cleansing and destruction of Palestine.’”

And yet I admit to being moved by Refaat Alareer’s poetic last will and testament, “If I Must Die.” Posted on X, just weeks before his death, it has since been translated into many languages and viewed almost 30 million times.

If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story

to sell my things

to buy a piece of cloth

and some strings,

(make it white with a long tail)

so that a child, somewhere in Gaza

while looking heaven in the eye

awaiting his dad who left in a blaze—

and bid no one farewell

not even to his flesh

not even to himself—

sees the kite, my kite you made,

flying up above

and thinks for a moment an angel is there

bringing back love

If I must die

let it bring hope

let it be a tale.

The poet’s instruction to his heir(s) to “sell my things” strangely guided me to recall the requests my parents and I made to refusenik friends who remained behind the Iron Curtain as we packed our bags to leave Russia forever in 1987. As for the overall thrust of the Gazan poet’s testament, I read it as straddling the line between self-mythologization (a common feature of this Horatian tradition) and self-martyrdom (a common aspect of Hamas culture). A child “somewhere in Gaza” who “look[s] heaven in the eye” and “await[s] his dad who left in a blaze,” what does this child see? A civilian victim or an Islamic martyr? The deliberate ambiguity festers at the heart of the poem.

As I reflected on the rapidly expanding mythology surrounding Refaat Alareer’s death, a mythology fraught with false pathos and forged hyperbole, I thought of the lives of Jewish poets during World War II and the Shoah. The late 1930s and 1940s added a new chapter, both tragic and inspiring, to the history of Jewish poetry. These were poets born between the late 1890s and late 1920s who wrote mainly in Yiddish, Russian, and Polish, and who all gained or regained their Jewish voices during the Nazi onslaught and the annihilation of European Jewry.

The Jewish poets who gave voice and form to Jewish victimhood and valor included Boris Slutsky, Yan Satunovsky, and Ion Degen, all of whom spent 1941-45 in Soviet uniform. Ilya Selvinsky, a major modernist voice, volunteered in 1941, served as a military reporter and political officer, and became the first poetic witness to the Shoah.

It was Selvinsky who, in January 1941, in the poem “I Saw It,” spoke of an urgent need to create a new poetics for writing about the murder of Jews:

No, for this unbearable torment

No language has been devised.

While the survivalist in Selvinsky didn’t avoid Stalinist dithyramb, the Jew in him kept rebelling against Stalinist antisemitism and obfuscation of Jewish victimhood. That was his poetic imperative, Soviet, Russian, and Jewish all at once.

The ghettos of Eastern Europe also birthed profound Jewish poetry of love, anguish, and resilience. The Yiddish poet Avrom Sutzkever and the Yiddish (later Hebrew) poet Abba Kovner escaped from the Vilna Ghetto in 1943 and fought in Jewish partisans units; after the war, both made Israel their home. Kovner, one of the organizers of the Fareynikte Partizaner Organizatsye (United Partisan Organization), later commanded the Nokhim (Avengers), a Jewish partisan unit. Vengeance was a leitmotif of Sutzkever’s work, such as this piece composed in the Vilna Ghetto:

My every breath is a curse.

Every moment I am more an orphan.

I myself create my orphanhood

With fingers, I shudder to see them

Even in dark of night

(translated by Barbara and Benjamin Harshav).

The Warsaw Ghetto, too, had its poetic chroniclers and avengers, among them Itzhak Katzenelson, who participated in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943 and later perished in Auschwitz in 1944. Władysław Szlengel, another Warsaw poet-fighter, was killed by the Nazis during the uprising. And there is a rich history of Jewish poets’ participation in the anti-Nazi underground in the occupied countries of Europe. Such was the case of the Bessarabia-born Dovid Knut, who was active in the Zionist resistance and rescue organization, Armée Juive, in Toulouse, and survived by escaping to Switzerland after being pursued by the Gestapo. Knut died in Israel in 1955.

And yet, the story of the Jewish poets’ valor, death and survival during World War II and the Shoah would not be complete without an acknowledgment of poets who weren’t naturally given to donning uniforms or fighting in the underground. The examples of both Raissa Bloch and Paul Celan offer precious evidence. Bloch, a St. Petersburg-born Jewish poet and medievalist, emigrated to Berlin, moved to Paris after the Nazis came to power, attempted to escape from France to Switzerland, was returned by the Swiss border guards, and died in Auschwitz in 1943. Paul Celan, a native of Czernowitz, lost his family in the Shoah, survived, became one of the defining voices of postwar German-language poetry before killing himself in Paris, in 1970.

In positioning themselves as poetic voices of the beleaguered Gaza, Refaat Alareer and his fellow Gazan poets have repeatedly drawn from this Jewish literary tradition, and have not hesitated to appeal to the historical memory of the Shoah or liken themselves to dwellers of the Jewish ghettos. Of all the comments Alareer made following Oct. 7, his BBC interview has received the most criticism for its pernicious comparison of the Hamas attack on Israel to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Such deeply ahistorical canards, seeking to draw a parallel to the Shoah and to Jewish resistance—false analogies that are also present in Alareer’s poetry—throw in sharp relief the fallacies of the poet’s historical imagination. Alareer and other Gazan poets simultaneously engage in appropriation of Jewish victimhood and adoration of anti-Jewish violence. In the finale of his poem “To Ghassan Kanafani,” featured in his collection Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear: Poems from Gaza, Mosab Abu Toha writes:

Shrapnel was the tattoo

marking your bodies

for the ghetto

of the Dead.

In 1972 Ghassan Kanafani, author and PLO functionary, was assassinated for his role in the deadly terrorist attack on the Lod (now Ben-Gurion) Airport.

While it is probably a futile task to disentangle such comparative knots, this much bears mention. During World War II and the Shoah, Jewish poets lived and died in different countries and under different historical circumstances, from the occupied European countries to European countries that were Nazi allies. Many of them, especially Soviet Jewish poet-soldiers, were people of multiple allegiances and had varied relationships with political ideologies, religious beliefs, and national cultures. Yet almost all of them were not only voices of Jewish resistance to Nazis and their accomplices, but also voices of Jewish rebellion against tyranny.

In contrast, poets of Gaza are voices of Israel-hatred by choice, and channels of antisemitism by default. I would love to see some evidence to suggest otherwise or at least to complicate this judgment. While the poets of Gaza may not have joined the Hamas battalions, they did not resist the rule of Hamas or condemn it, and in many cases they also sang from the song sheets of Hamas propaganda. While it’s probably too much to expect that poets living in a society ruled by such extreme totalitarianism would resist, I think it’s not too much to ask that the poets of Gaza acknowledge their predicament and blame not Israel but their own fanatical regime.

In order to unravel the internal conflicts and external tensions that fueled the poetic engines of Refaat Alareer, I examined his recent discursive public statements. More disturbing—and also more symptomatic—is Alareer’s assessment of the Hamas attack, in the aforementioned BBC interview, as “legitimate and moral.” On Oct. 29, responding to reports that on Oct. 7, an Israeli baby was found baked in an oven, Alareer tweeted the following horrendously cruel joke: “With or without baking powder?” I imagine Holocaust-deniers trading such jokes in their dark chatrooms.

On Nov. 29, Alareer tweeted: “When Israel ran out of lies, it regurgitated the rape and sexual violence lie. The first to get the Zionist marching orders is this UN racist Antonio Guterres. ALL the rape/sexual violence allegations are lies. Israel uses them as smokescreens to justify the Gaza genocide.” A few days later, he tweeted: “We could die this dawn. I wish I were a freedom fighter so I die fighting back those invading Israeli genocidal maniacs invading my neighborhood and city.”

It is quite impossible to separate what Alareer said in public statements, in his state of rage and distress and in anticipation of death, from what Alareer the poet put in verse. Impossible, not only because he speaks as a Hamas fighter who has not (yet) put on a uniform, but also because his two sides, discursive and poetic, are so synchronized.

I imagine it is no easier—at least for the younger crowd in the West now lionizing Alareer—to make these distinctions. A recent survey of college students by the political scientist Ron E. Hassner revealed deep ignorance about the basics of the Arab-Israeli conflict. The current wave of anti-Israel activism betrays a romantic notion of Hamas as an anti-colonial resistance force rooted in the traditions of the international socialist movement. Nothing could be further from truth, and yet this embellished, poeticized perception of the mission and methods of Hamas obscures much of what goes on in Gaza and what emerges from Gaza, including poetry.

Perhaps what Alareer’s death conjured up for me most powerfully was Roman Jakobson’s mournful essay, “On a Generation that Squandered Its Poets,” written in response to the suicide of Vladimir Mayakovsky, a peerless voice of the revolutionary avant-garde. On April 14, 1930, Mayakovsky committed suicide, no longer capable of bearing his own complicity and compromise with the Soviet—Stalinist—state. I thought of Jakobson’s essay not because Alareer, a conventional nationalist “poet under fire,” was anything like the cosmopolitan genius Mayakovsky. Rather, I remembered Jakobson’s essay because it articulated with ruthless precision how a poet’s death betokens not only his disappearance from a cultural generation but also what’s wrong with the generation itself: “Sheer grief at his absence has overshadowed the absent one. Now it is more painful but still easier, to write not about the one we have lost but rather about our own loss and those of us who have suffered it.”

Poets dwell in a state of acute intimacy with language. Yet some poets choose to live in a state of denial that this acute intimacy with language also makes them, whether they like it or not, instruments of violence and intolerance. I’m saddened by the death of a poet, any poet, but I also know that some poets choose to die as agents of intifada, not prophets of art’s healing powers. And I also know that the Hamas regime would rather see its poets murdered and martyrized than evacuated and saved. Such was the short, turbulent life of Refaat Alareer, teacher of Shakespeare’s sonnets, poet from Gaza whom his own society sacrificed on the altar of Israel-hate. May he rest in peace, when peace reigns again in Gaza.

Maxim D. Shrayer is a bilingual author and a professor at Boston College. He was born in Moscow and emigrated in 1987. His recent books include A Russian Immigrant: Three Novellas and Immigrant Baggage, a memoir. Shrayer’s new collection of poetry, Kinship, will be published in April 2024.