Is This Story Real?

A manuscript of a Holocaust tale published in France roped scores of people into a mystery. Including me.

It is evening at the Brasserie Lipp, on the Boulevard Saint-Germain in Paris.

The fall after-theater crowd shrugs off furs and foulards, as waiters take balletic strides in ankle-length black-and-whites, balancing plates of choucroute, andouille, and Bismarck herring. Signs warn against feeding les chiens at the table, or expecting to pay by check. Painted angels on the ceiling, yellowed from ancient smoke, watch over Art Deco ceramic panels of cockatoos frolicking in palms and prickly pears. Flouting the rules, a lapdog pants on the red moleskin banquette. Everything is multiplied in wall-sized mirrors, such that among the thin columns and glass dividers, there is almost nowhere to look chez Lipp without seeing some version of yourself.

Lipp’s regulars have included Chagall, Camus, Sartre, and Simone de Beauvoir. French Presidents de Gaulle, Pompidou, and Mitterand (and his extramarital daughter) were all regulars. The tables—in one of three sections, known (never out loud) as purgatory, the aquarium, and paradise—have hosted Bergman and Rossellini, Jagger, Madonna, the archbishop of Paris, and France’s most offensive pornographic filmmaker. Ex-President Bill Clinton was denied Coca-Cola on the terrace, because Lipp does not serve Coca-Cola. A Moroccan nationalist was lured here to be “disappeared.” Ernest Hemingway loved Lipp: “The beer was very cold,” he wrote, “and wonderful to drink.” Another habitué, French aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, creator of The Little Prince, crashed his prop plane in the Egyptian desert attempting a Paris-to-Saigon speed record in 1935, but five days later, as the legend goes, thought lost forever, he walked through Lipp’s revolving wood-and-glass doors to astonished cheers. The owner poured free champagne until 3 a.m.

Or so they say. That’s the kind of place Lipp is—a place of a thousand stories—and has been for 135 years.

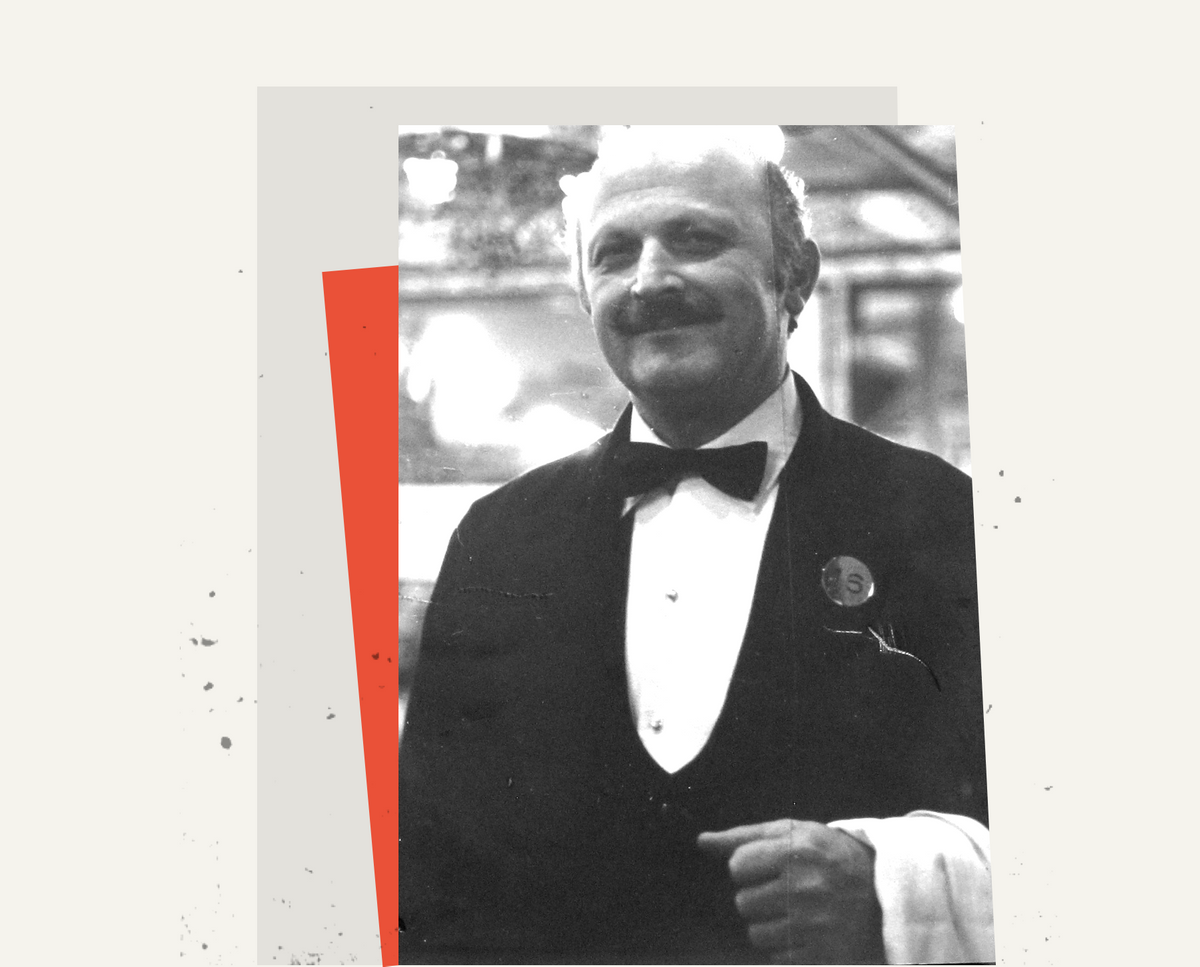

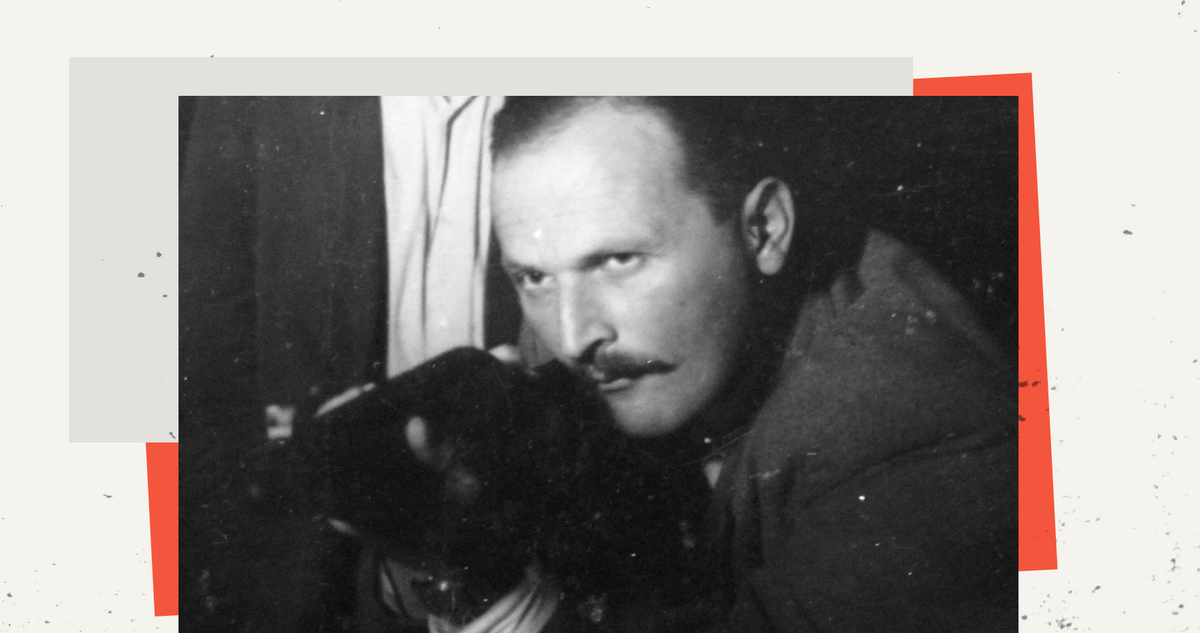

Monsieur Serge, as he was known, was for most of his adult life a waiter chez Lipp. In his late 30s, already bald save for a horseshoe-shaped tonsure, he wore an elegant mustache, pointed at each end, that echoed the faint trace of the Eurasian steppes sharpening the corners of his eyes. He was broad-shouldered, handsome, and a hard worker, capable of long stints of physical activity without rest. Polite and courtly, he delighted in the electric atmosphere of Lipp’s self-infatuated dinner theater—but with Gallic discretion, he never fawned. He engaged his clients with a lilting foreign accent that seemed to come from everywhere and nowhere. Everyone loved Monsieur Serge. No one knew him.

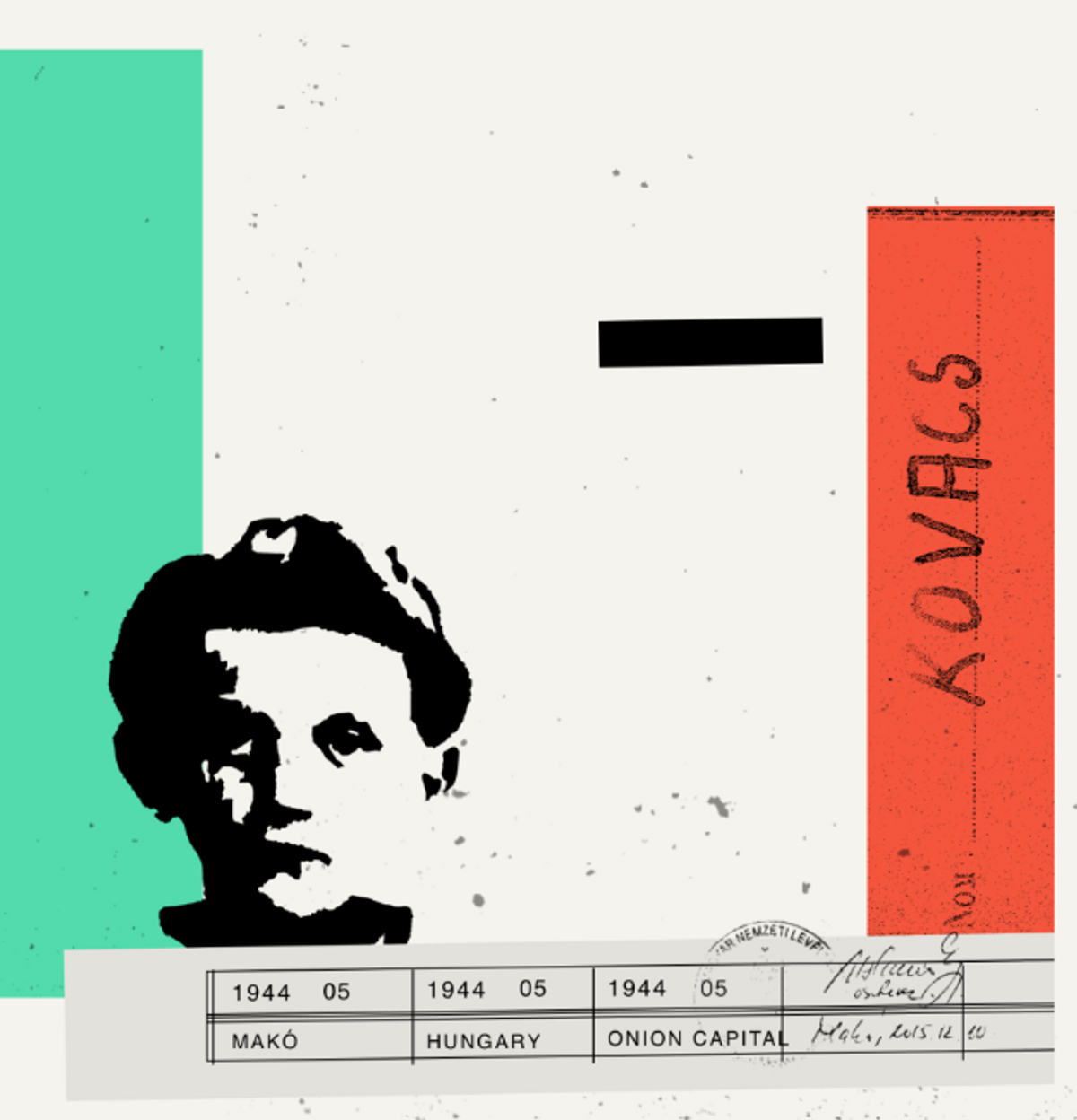

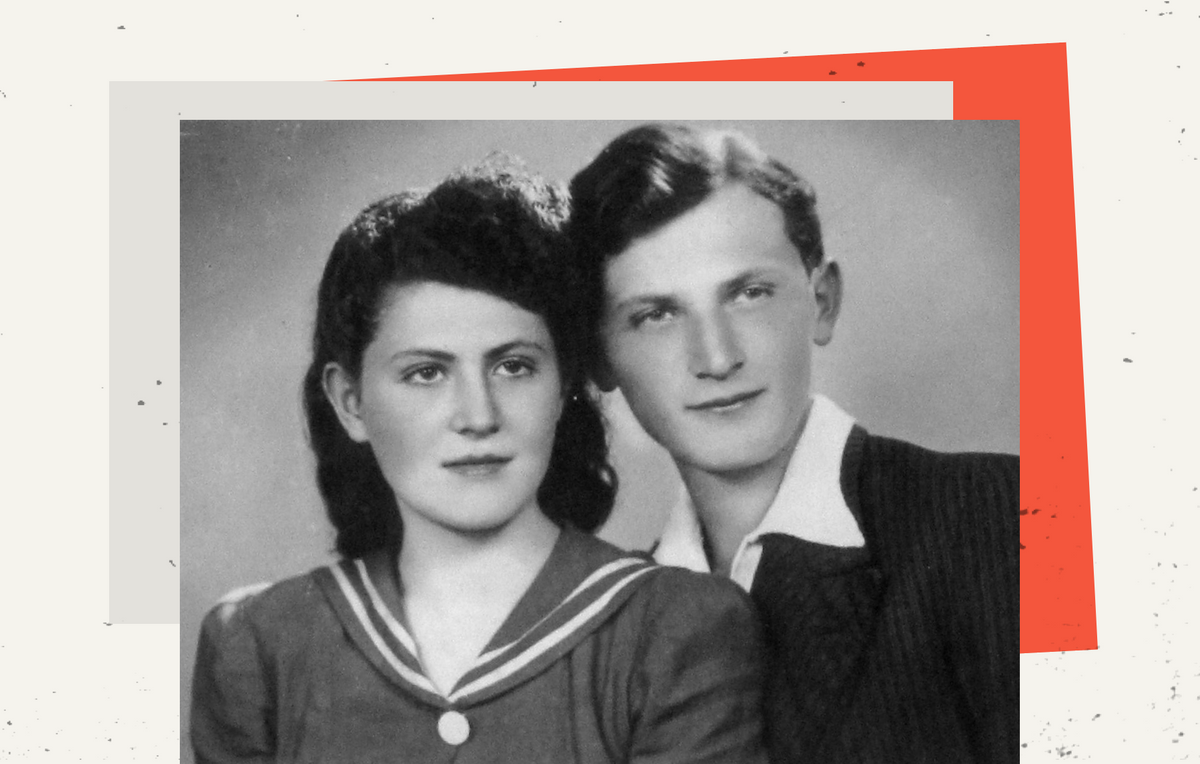

That’s because Monsieur Serge kept his private life to himself. Some of his co-workers in 1960s Paris gathered he was a Hungarian Jew named Imré Kovács, born in 1926 in Makó, a small town not far from the Romanian border. The vague outlines of his past life circled as rumor: He was raised a peasant, along with his sisters Klari and Margit and his half-brother Laszlo. His father was a veteran of the Great War. His mother, Ilona, was a devoted housewife. They were not deeply religious, but they were Jews, and that, as much as anything, determined their fate. That much was known.

What his colleagues at Lipp didn’t know was that as a young man, Imré Kovács had escaped the Hungarian fascists. How he had done this was not something he seemed to be interested in boasting about at work. Unlike Lipp’s patrons, the staff there inhabit a great anonymous dignity. They are given numbers one to 25, which they wear pinned to their lapels. The career garçons come from demanding apprenticeships or Lipp lineage, or else they have bought their way in to what is a lucrative job for the field. They handle their clients with unobtrusive hustle, hauling trays up 23 cramped steps from the basement kitchen. Equal parts stagehand and Greek chorus, they spend their days and nights asking how everyone is doing, never to be asked it in return.

Had anyone broken through Monsieur Serge’s defenses, though, they would have heard an amazing tale about infiltrating the 26th Waffen-SS, the 2nd Hungarian Division of the German elite fighting force. He might have told them about surviving a brutal Soviet POW camp and spying there for an international Zionist intelligence ring. Or about joining the armed resistance in Palestine and seeing the birth of the State of Israel. Or he might have talked about tracking former Nazis in Indochina and Algeria after the war, meting out vengeance through assassination plots in the French Foreign Legion. But that was Imré Kovács. Monsieur Serge was a man with a wife and eight children in Paris, a waiter chez Lipp.

In some ways, each of these creations invented the other.

In September 2003, Serge Kovács, Imré’s eldest, received a phone call telling him in halting French that his father had died. It had been years since they had seen each other. As a parent, Imré had been a reserved and mercurial man who worked late nights and weekends and left his children to fend for themselves. Still, Serge felt his filial duty and a great loss. He flew to Budapest, and then made his way to Orosháza, where his father had decided to spend his last years.

Imré had died at home. Responding to complaints of a stench, the local police had subdued his two famished dogs and broken in the door to find him face down in a pool of blood. The cause of death was thrombosis. He had been rotting for four days. With no family nearby to claim him, Kovács had been buried in an unmarked grave.

To locate insurance and pension records, Serge had to rummage through the disorganized papers of a demented old man. Among the clutter, in Imré’s bedroom, there was a wooden Hungarian armoire, rustic and worn. A mirror inside the door reflected Serge as his father might have seen him: 46, divorced, and now orphaned. On the shelf, he found an orange folder with elastic bands that contained about 100 pages of photocopied typescript. Distracted by his guilt and grief, Serge decided to bring it home with him to Paris, along with the Hungarian death certificate, to coordinate matters with his siblings.

In France, Serge sat down to read the unfamiliar text from his father’s closet. Within a few pages, he realized that he held his own father’s life story, which Imré had probably set down two decades before. The epigraph, from Leviticus 19:34, read: “You shall treat the stranger who sojourns with you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.” The need to write down his wartime experiences had never left him, Imré explained in his typescript, but time had to pass for his wounds to heal.

It was not a ragtag tale of survival but an epic, full of amazing exploits.

“It was a miracle that any Jews survived,” he wrote, “but each miracle was different for each survivor. Most of the victims, especially those who were the strongest believers, have become atheists. For my part, the contrary happened: Ever since, I am certain God exists.”

As if in a trance, Serge read it in one sitting. It revealed a father he had only the smallest hints ever existed—nothing like the carefree Parisian bistro waiter. Some of the episodes were vaguely familiar, but much of it was a revelation. Like many children of Holocaust survivors, Serge knew merely the rough outlines of his family’s history. At home, the subject had been taboo. But here in his hands was all the missing detail that his father had never opened up about. And it was not a ragtag tale of survival but an epic, full of amazing exploits.

Serge was stunned. My father, a Hungarian Jewish peasant—could it all really have happened like that? The stories seemed incredible. But there it was. Serge understood that he would have to publish his father’s account of his life.

The first chapter, “The Orphan of Makó,” begins with Imré’s mother Ilona calling three of her four children to dinner: “Klari! Margit! Imré!” We are in the onion capital of Hungary, a prelapsarian idyll of happy Jews before the war. “My mother,” Imré writes, “I can hear her like it was yesterday.”

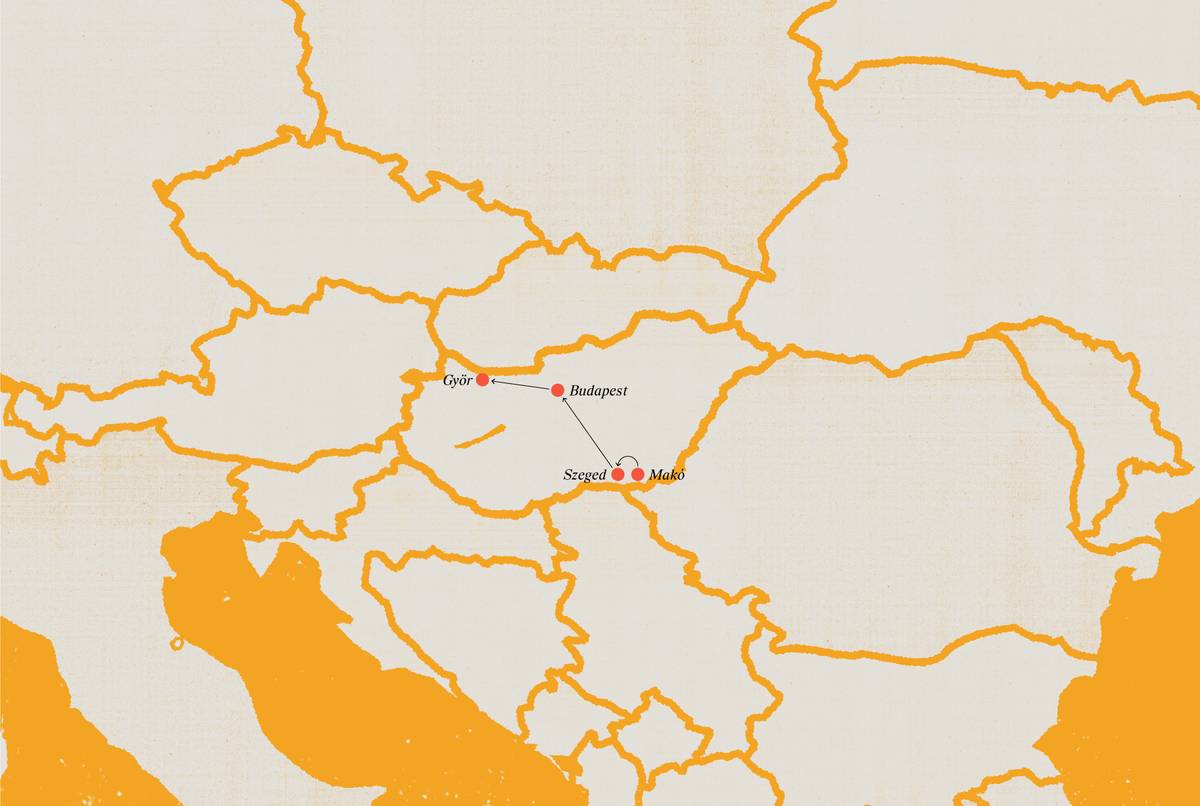

By May of 1944, Imré Kovács needed underwear. His family’s sudden forced removal to a Jewish ghetto in Szeged that month left him without his things. On orders of the German occupation government, thousands of Jews have been confined to a few city blocks in Budapest and in the provincial capitals. In Szeged, Ilona finds a small room and learns to barter for smuggled rations. She cuts a pillowcase and lovingly sews the pieces into something Imré can wear.

It’s a confusing and shocking turn from the modest comfort Imré knew as a child in the 1930s. Sure, word had trickled in even to his family’s small farm that, to the north, in Poland, the mass deportations and killings had blossomed into a full-blown extermination campaign, but he and many other Hungarians remained incredulous, or stunned into inaction, or otherwise helpless.

The war came to Hungary with breathtaking speed. In just two short months after March of 1944, German troops occupied the country and propped up the puppet fascist Ferenc Szálasi in Budapest, who in turn deployed the murderous Arrow Cross paramilitary. By April, Imré and his sister Margit—way out in rural onion-growing territory—had been arrested for refusing to wear the yellow star identifying them as Jews. By May, mass deportations had begun. Within 56 days of occupation, 440,000 Hungarian Jews would be sent to Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen

In Szeged, Ilona is ordered to the train station.

She turns to her boy, 18 at the time, still fit from farm labor, and asks, “Imré, you love me, don’t you?”

“Yes, Mother,” he answers. “You are the dearest thing in the world to me.”

“Then promise me you’ll use all your strength, your whole life, to help the weak, the small, and the oppressed,” she says.

“I swear it, Mother,” Imré says.

He does not want to leave her, but he knows he must, if he is to escape.

This late stage of the war’s Eastern Front is a race. On one side, the retreating Nazis, trying to deport and exterminate as many Jews as they can—a madness of ruin. On the other, the Russian Red Army, surging across Romania like a rising tide, washing over the chaotic Hungarian border in pursuit of the increasingly bedraggled and outmanned fascists. Once a prosperous land of onion farmers, the region is now a hectic morass of soldiers, villagers, and desperate citizens with nowhere else to go, packing what they can and beating a path back to Budapest. To get there, the refugees must cross the plain between the Tisza and the Danube rivers, where wild horses run and where a mirage known as fata morgana makes cowherds appear to float upside down on the summer horizon.

Out of the ghetto and having said farewell to his mother, Imré tracks down a farmer with a horse-cart, which he shares with Mátyás Gajdács, a young architecture student at Budapest’s beaux-arts school. But then Gajdács remembers that he left some important things with his aunt on the other side of town. The Reds are bearing down on them, so Gajdács agrees to ride his bicycle to a rendezvous point near a bridge. Tragically, he is cut off by a turn in the battle, and never arrives.

Kovács and the farmer decide to press on to Budapest without Gajdács but are stopped at the Danube, where all the bridges have been blown out. Ferries are pressed into service, but people jump into the river and drown rather than wait to be strafed or bombed by Soviet aircraft. Those who survive the passage arrive at a Hungarian capital convulsing under Szálasi’s reign of terror. His Arrow Cross paramilitary squads are rounding up Jews by the thousands to be sent in cattle cars to concentration camps. Fascist sympathizers are shooting Jews in the streets and throwing the bodies into the river. Checkpoints blanket the city. Hearing of this, Kovács grabs Mátyás Gajdács’s papers and assumes his identity.

Kovács and the farmer are pressed onto an Austria-bound military train by a Hungarian officer. Heading north, Kovács witnesses lines of Jews deported out of the ghettos, marching to their certain deaths in the cold and snow. Is his mother among them? As he tells it, a mysterious bloodstain appears on the underwear she’d made for him. He takes this as a sign she is lost to him forever.

Győr, near the Austrian border, crawls with German and pro-Nazi Hungarian soldiers. The walls are plastered with posters of wild-eyed Bolsheviks with knives in their teeth and patriotic appeals to join up to defend the country from the Communist invader. Kovács takes shelter there with a family and befriends the 20-year-old daughter of the house, Ilonka, whom he gallantly escorts home from work.

Later, whiling away the hours in Győr, Kovács comes upon a magnificent neo-Gothic synagogue, much larger than any he has seen. It is closed: Thousands of Jews have already been deported from the region. But with his borrowed papers, Kovács has little to fear. He seeks a way in, when suddenly the temple door swings open.

“Sir, are you looking for someone?”

The speaker is a man in his 20s, not Hungarian at all. Kovács says he isn’t looking for anyone in particular. He wonders, though: What has become of the Jews of Győr? And Makó?

The man asks in Hebrew: Are you Jewish?

In his telling of it, Kovács doesn’t hesitate to answer yes, despite the obvious risks. Kovács is invited inside. He says he is from Makó, has seen the doomed Jews, suspects his mother is in Germany or worse, and wants to find her. Thanks to his false papers, he declares he has some freedom of movement.

The man says his name is Yossef. He says, “There is something you can do. But be warned: It’s extremely dangerous. If you are found out, there will be no saving you.” He goes on: In town there is a recruitment post for the newly formed Hungarian divisions of the German SS. The commander is Hungarian, but the men wear German uniforms, and many boast German ancestry. They are to bring glory to fascist Hungary and the Reich, a gift from Szálasi to the Führer. Kovács listens. Yossef continues, explaining the value of a mole for the Jewish resistance. “Tomorrow, you will go to the bureau,” Yossef tells Kovács. “You will sign up.”

Nervous young men fill the Nazi recruitment office in Győr. None are more nervous than Imré Kovács. His papers identifying him as an architecture student have served him in the current chaos, but they can do nothing to grow back his missing foreskin. One by one, the youths are called up for their physicals. Leaving now would only be suspicious. With each called name, Kovács’s fear grows. As it grows, so his sex retreats and shrinks until it can barely be seen. A miracle! His circumcision goes undetected. He is to report to the train station the next day as an enlisted member of the Waffen-SS.

Determined to bring his father’s story to the world, Serge Kovács set about finding a publisher. An old university classmate of his named Frédéric Ploquin brought Kovács’s manuscript to his editor, the French titan of letters Claude Durand, who championed Solzhenitsyn and first introduced magical realist Gabriel García Márquez to French readers in his own translation. Though Durand was amazed at the heroics of the placid waiter from Lipp (where Durand often lunched), he had reservations. Was it a fantasy or a true account? Durand suggested that a story about Hungarian Jews might be too obscure for his readership, so he agreed to consider the manuscript on the condition that Ploquin and Serge find evidence for all the claims and that they write interstitials and introductory material to situate the rough-hewn, naïf tale in the historical context of the Second World War.

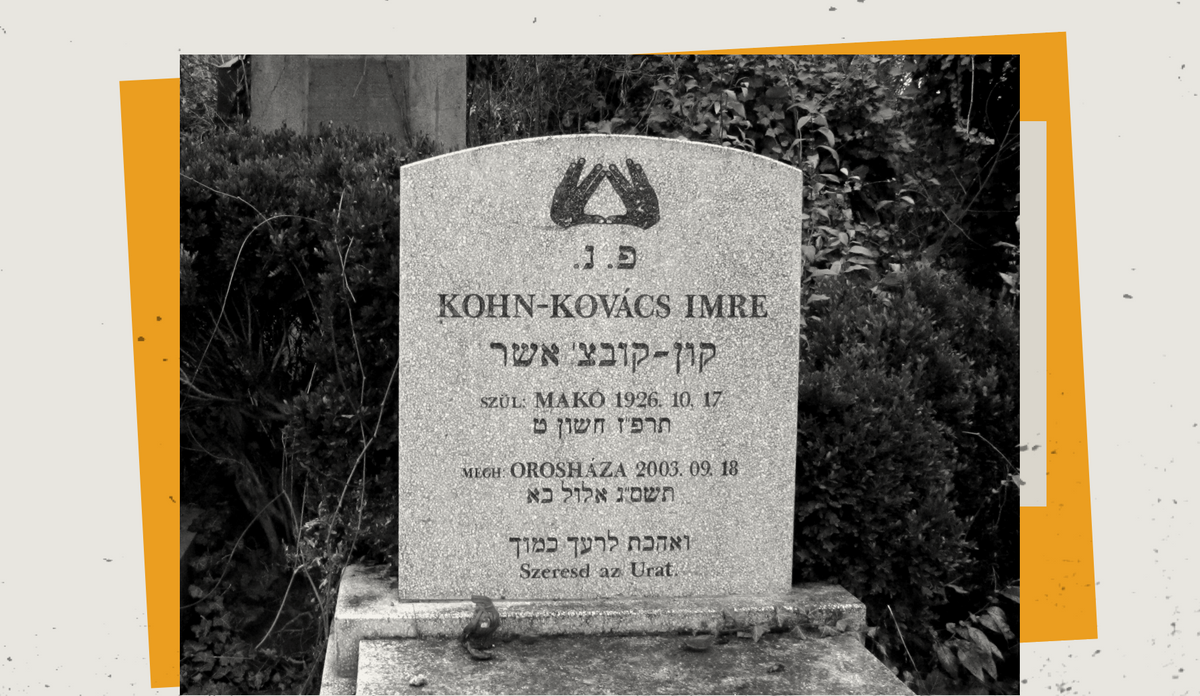

Ploquin and Serge would get 4,000 euros in advance and split the royalties. But Serge hesitated. Should they wait out a year of shiva, in the Jewish tradition of grief, before launching something so important to his father’s legacy? Financial pressures nudged things along. Imré’s neighbor in Orosháza, Erzsébet Boldog, called to say she had sold all the furniture: What was to be done with the house? It would shortly be foreclosed on. Meanwhile, Imré Kovács still had no tombstone, and Serge had no money to pay for one. So Serge went back to Ploquin and said, “OK, let’s do it,” using the advance to fly to Hungary, sell the house, and track down a marble worker in Makó willing to trace Hebrew letters out of a Bible—and etch the hands raised in blessing that symbolize the Jewish priestly clan, the kohanim—for a gravestone. A rabbi from nearby Szeged would officiate at a proper Jewish funeral.

Back home, on Durand’s orders, Ploquin and Serge hunted for evidence of Imré’s many adventures. Serge checked place-names and returned to Hungary to try to pry open local archives that had for years been closed to the public. Hungarian names turned out to be German names for Polish locations. Anachronisms complicating the plot had to be untangled. Ploquin, meanwhile, wrote about the village of Orosháza, where the typescript was found, and set up the broader tale. As best he could—admittedly no historian—Serge described the state of Jewish resistance in 1942, the movement of Soviet troops across the Eastern Front, the fall of Berlin and the liberation of the camps, and the catastrophic loss of Hungary’s Jews. (Churchill would come to call the persecution of Hungary’s Jews “probably the greatest and most horrible crime ever committed in the whole history of the world.”) He wrote about the Mandatory Palestine to which his father emigrated after the war and described the French Foreign Legion of the 1950s and its quagmires in Indochina and Algeria. And Ploquin rounded it out again with a meditation on Hungarian complicity in the war and the nature of unfinished justice.

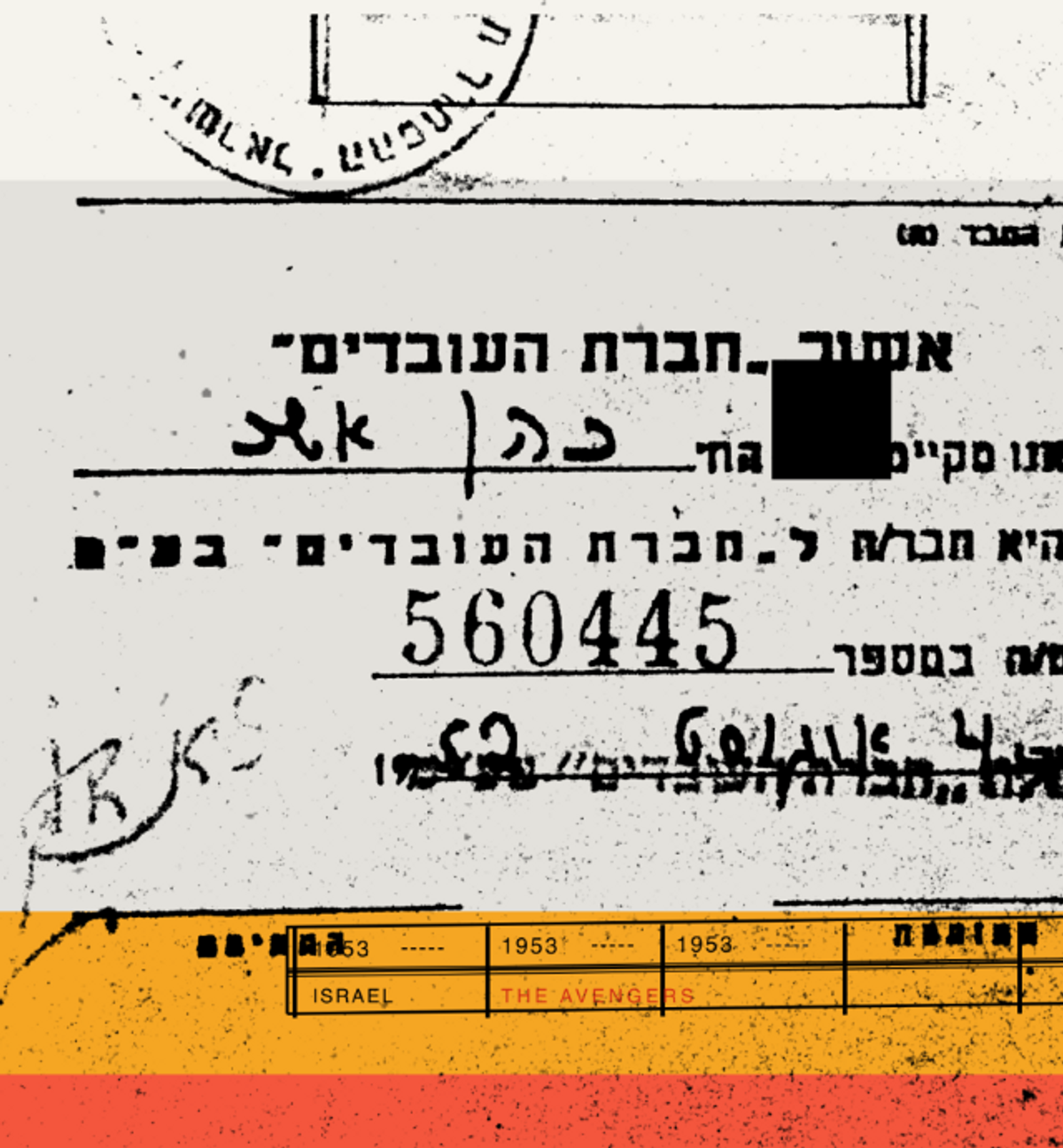

Serge wanted to title the book “Le Justicier” (The righter of wrongs), but Ploquin and Durand both thought their best chance at sales was to call it Le Vengeur (The avenger), highlighting Kovács’s pursuit of “les criminels nazis”—a small part of the book—over his less exciting adventures as a refugee and prisoner of war.

Kovács’s story can be read as a universal fantasy of power and revenge, a pleasing revisionist view of the war, in which Jews are no lambs to the slaughter.

When the book came out, Serge showed it to his brothers and sisters, who had left him in charge of estate matters, largely out of indifference. Their reaction was not good. A number fairly wondered why they had not been consulted. One sister complained that Serge had sold the rights for too little. Another questioned why Ploquin had to be involved. Ploquin traveled to Nice, where Serge’s sister Nathalie lived, to try to convince her otherwise. A third sibling, upon hearing that a Hungarian film company was interested in making the book into a movie, sued the editorial house to get the rights back. Ploquin, embroiled in the family drama, fell out with Serge. The crux of the argument, besides money, was this: Did Imré ever want to publish his manuscript? Did it reflect on him well? Was it true? Serge believed his father’s story was true, and believed he wrote it in order to publish it, not to leave it in a closet. At least one brother strongly disagreed; Serge and he no longer speak.

When Fayard published Le Vengeur in 2006, the critical response, though not broad, was wide-eyed: How could such a heroic figure have passed unnoticed among us? (“The French elite”—meaning Lipp’s regulars—“couldn’t imagine that ‘M. Serge,’ the longest-serving waiter at Lipp, was a former Nazi hunter,” read one review.) But sales were modest.

In print, Kovács’s story isn’t just his own personal fantasy of Jewish heroism and daring; it can be read as a universal fantasy of power and revenge, a pleasing revisionist view of the war, in which Jews are no lambs to the slaughter. Kovács’s exploits were the hidden secret of a mild-mannered waiter, an affable but otherwise unremarkable bon vivant. Maybe elsewhere in France, with its dark history of capitulation and collaboration, there were other secret heroes

When I met Frédéric Ploquin at Le Nemours, a café in Paris, on a rainy December evening, I asked him about the book: “Is it true?” Ploquin’s manicured look did not betray any of the fearlessness he had shown in writing several highly acclaimed exposés of organized crime and jihad. He pursed his lips into a pout and sucked air through his teeth: the French equivalent of a shrug. Then he reached across the table and pointed to the back-cover blurb he had written 10 years before. Le Vengeur is a temoignage, or “testimony,” not a history or report or investigation. “If Serge’s father made things up,” he said, “those are the dreams and nightmares of the Holocaust survivor. It might be fantasy, but those fantasies still tell us something.”

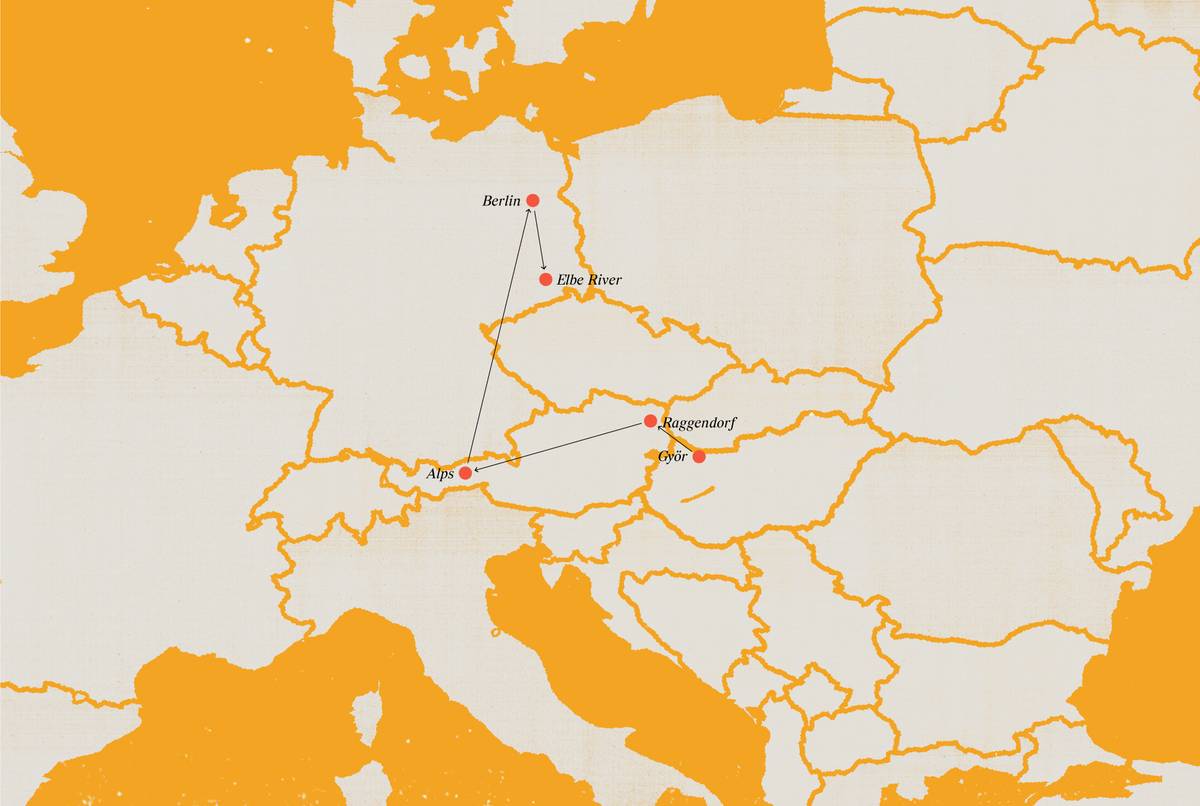

In Raggendorf, over the Austrian border, Imré Kovács dons the uniform of the 26th Hunyadi Division: an eagle on the chest, death’s head on the cap. The other 16- to 18-year-old fascist recruits proudly display their new finery in town that night, while Kovács, still under the alias Mátyás Gajdács, uses the password Yossef has given him to contact another Zionist operator there, Isaac. The secret-agent ring Kovács has happened upon is international, and this agent is a sabra, born in Palestine. They have come to save Jews and fight the fascists. They are masters of falsifying papers, and of stealth, protected by Protestant clergy. How did they get here? They know a lot about the SS but need Kovács’s intelligence, now that on their orders he has infiltrated the Nazi guard.

Strong and fit, Kovács is sent into an elite alpine unit of the SS in Austria, where he trains for several weeks. On a free day, he uses a password at a Protestant church to meet Ygal, who connects him with Haya, at his next posting in the Alps. Kovács skis in the morning, manipulates explosives in the afternoon and, whenever he can, jarringly, claims to court a beautiful young Austrian Zionist rebel in the nearby town. She wants to know more about the high command, and so Kovács gets himself hired as the aide-de-camp to the Obersturmführer Schroeder, who takes a liking to his obedient valet. Thinking that his name is Mátyás Gajdács, Schroeder calls Kovács King Mátyás, in honor of the large nose he shared with the great 15th-century unifying Hungarian ruler of the same name.

Abruptly, the narrative jumps to Berlin, January 1945. Kovács wanders the city in his SS uniform, and stops at a department-store Fotomat for an admiring self-portrait in his sheepskin jacket over Nazi black cloth. The city is in partial ruins after repeated bombings. Hitler has retreated into his Führerbunker with Eva Braun. Sirens go off, and ragged German servicemen get what pleasure they can as the Red Army marches west. Schroeder and Kovács are given R&R passes to the Ballerina nightclub, where the evenings begin with a striptease followed by a dance. For a fee, patrons can take girls upstairs. The brothel is the same place, as it happens, where a Zionist agent named Sarah is stationed. Though the club is dry (save for weak lemonade), Schroeder encourages his faithful servant to indulge in the lascivious offerings. Kovács tells the madam he’ll have no other except Sarah, whom he claims to know. But Sarah is … occupied. So he waits.

At midnight, the blue-eyed, dark-haired female spy approaches. She’s not a day over 22. “Do I know you?” she asks. “Yes,” he says. But she doesn’t appear to believe him. She’s seen many men, too many to know them all, and anyway the fee has been paid. She takes Imré upstairs to her small room, lays down seductively on the bed, and beckons to him.

“I’m not here for that,” he says. “Haya sent me.”

Once over her shock, Sarah tells Kovács that they cannot stop the Germans from finishing their secret weapon, the atomic bomb. The only thing they can do is help speed up the meeting of the Soviet and American fronts to end the war first. The exhausted Germans are throwing their fresh young Hungarian divisions at the most important battles, she says: Any information on the whereabouts of those troops will be invaluable to the Allies.

Kovács sees the logic, and the danger to himself, of delivering his camp’s positions to Allied bombers. Sarah does, too, and, being the older and more daring of the two resistance fighters, reassures Imré Kovács of the worth of his sacrifice. As Kovács tells it, fateful and full of abandon, they fall into a bout of passionate lovemaking.

Those are the dreams and nightmares of the Holocaust survivor. It might be fantasy, but those fantasies still tell us something.

Not long after, Kovács—an alpine chaser and SS machine gunner using the name Gajdács—is caught in a shallow trench on the bank of the Elbe River with a dozen other Waffen-SS. Gunfire echoes in from the nearby village, where Communist partisans have holed up. Bullets ricochet off a milestone pointing to Prague. A radio call for reinforcements goes unheeded: The nearest division is in combat with the Red Army. Trapped, the SS squad leader decides to risk a quick retreat to the opposite bank, across a bridge, behind a dike. The first to run takes a bullet through his stomach. His guts explode. He screams, “Kill me!” A last leftover smoke bomb misfires, so the Nazis’ only hope for cover is to launch rockets.

Dudás, an SS soldier, jumps up to throw a grenade and ducks back down into the trench. Kovács braces for the explosion that doesn’t come. He sees then that Dudás is still clutching the grenade.

“What are you waiting for?” Kovács cries.

Dudás rolls over to reveal a stream of blood on his forehead. He has been shot—but by some grace, he has not had time to pull the pin.

Imré Kovács realizes the direness of his situation in the exposed trench and prepares for his early death, when, pressing his ear to the ground, he hears the rumbling of German reinforcements behind him. A tank! It aims its cannon at partisan headquarters in the village. The enemy waves white flags. One of Dudás’s friends coldly plugs a bullet into the head of a partisan, declaring things even. The other SS loot the homes and finish half-eaten meals abandoned in haste; Kovács changes into fresh stolen underwear and keeps a wristwatch. The rest of the villagers and fighters—60 of them by Kovács’s count—are herded into the town square. SS soldiers set automatic weapons at the four corners, and massacre them all.

Eventually, Kovács is caught by the Russians as the war comes to an end. He discards his former SS identity, taking back the name Imré Kovács. He is marched, along with other Hungarians, four days and four nights to Wrocław, Poland, where a co-religionist from Makó puts Kovács in touch with a sympathetic Soviet camp officer. Kovács asks about his mother. He’s told that most Hungarian Jews were sent to Bergen-Belsen, now destroyed by the Allies.

“The war’s over,” Kovács says bitterly. “Let me go back to Hungary.”

“I can’t and furthermore don’t wish to liberate you,” the officer says, after hearing some of Kovács’s recent exploits. “For us, the Jews, the war is not over. The Nazis who committed unspeakable crimes like the one that ended your mother’s life must be tracked down and punished, one by one, in the name of all dead Jews.”

Naively, Kovács asks what he could do.

“You will be a friend to the Soviets. You must stay with the prisoners. That is your calling. And when the time comes, I will contact you.”

Passed by cattle car from camp to camp, Imré Kovács, now a prisoner of the Soviet Union, crosses Transylvania and Moldavia, battling dysentery. He lands in labor Camp 6, in the Black Sea port of Odessa, where he’s put to work breaking down the remnants of destroyed ships. The Soviets are eager to find the war criminals hidden among the ranks of the captured. In the camp yard, naked prisoners are made to stand with their hands on their heads, to identify former SS by the blood-type tattoo under their left arms.

Like the others, Kovács is interrogated. He bravely decides to tell the truth about his Jewish espionage, which somehow leads him to another spy handler, who enlists Kovács for his next task: to sniff out the untattooed later recruits to the Waffen-SS as well as the rearguard killers who organized the deportation and extermination of Jews—hiding now as simple German soldiers unlucky enough to be prisoners of war. Kovács is sent to a labor camp in a quarry, a brutal, harsh, cold place. His assignment is to listen for confessional remarks or signs, to spot the criminals as they reveal themselves through trust or carelessness. Eavesdrop, he’s told. Locate the worst commandos of the concentration camps. Where had they really worked? What had they done? All this information was to be gleaned by subterfuge, camaraderie, and close contact in the camp, where Kovács would have enough of a struggle just to survive. To maintain his cover, Kovács must not be treated differently from his fellow prisoners.

Isolated on a frozen high steppe hundreds of miles from Odessa, Kovács and the other POWs in four barracks cut and shape 26 stone blocks a day to earn a ration of 50 grams of bread, half a teaspoon of sugar, and a meager ladling of rotten potato gruel. As the winter of 1945 takes hold, stores become ever more scarce. First the dogs are eaten. Hunger gnaws at the men, and even the cook who bartered extra food for homosexual acts has nothing left to offer. The worst comes in the spring of 1946: The frozen trash heap thaws to reveal potato peelings mixed in with human excrement. Returning from work, the famished prisoners pounce on them and stuff what unclean shreds they can into their mouths before they are beaten back by guards. With no medicine or doctors, 15 to 20 prisoners succumb to typhus every day, their bodies tossed into unused parts of the quarry. By late spring, of the 3,100 prisoners who had departed Camp 6 for the quarry, only 124 are still alive. More die during their transfer back to Odessa.

Why does Kovács survive? It is no coincidence or feat of fitness or guile. God, he writes, has kept him alive—not as a privilege or a mystical expression of good or even evil. He simply isn’t done with Imré Kovács yet.

The freedom to fictionalize is after all one of the great luxuries of life—to invent stories, sometimes about yourself.

Spring rolls into summer. Kovács labors in potato fields and then on brigades reconstructing bombed-out Odessa. He finds ways to steal and barter for tobacco and food, and regains the weight he lost in the quarry.

On labor gangs that season, at a damaged but inhabited apartment building, Kovács falls for a beauty by the name of Natacha, who reminds him of his mother. Natacha speaks four languages and at 18 is already in her fourth year of medical school. He writes that her skin is peachy, somewhere between velvet and silk, and her lips are the clichéd ripe cherries. Her golden hair shines like a field of tall wheat. Demure and angelic, Natacha is also self-aware, just as Kovács’s mother was, perhaps her greatest quality. Imré and Natacha form a mysterious bond, talking about Hungary, art, and culture. The topic of a local opera production of Strauss’s The Gypsy Baron comes up, and they decide it would be fun to see it. But how? He is a penniless prisoner with nothing but filthy work clothes. The arrangement sounds ridiculous, but in truth the postwar border zones were chaotic ruins where captive and guard were largely interchangeable concepts.

Natacha’s father meets the charming if ragged suitor. He promises to speak with the camp commander, a friend, to request leave for Kovács, on his honor, so that they might attend the opera. Natacha arranges for her father to loan Imré suitable costume; as it happens, her father and Imré are the same height and build.

The next evening, Natacha’s father collects Kovács at Camp 6 and brings him home to bathe and change into his eveningwear. Kovács catches himself in the mirror. After years of war, flight, and servitude, he barely recognizes the civilized man he sees there. The company eats a festive meal prepared by Natacha’s mother and head to the show. The Odessa opera hall, now in 1946, is packed with newly hopeful citizens. In their loge, Kovács spends the time admiring Natacha and holding her hand. He can hardly believe it’s all real.

Back at Natacha’s home, Imré and the father have a man-to-man talk over vodka and cigars. Imré tells the father of his serious intentions toward Natacha, a proposal that is met with pleasure. The father happens to be Jewish, though not practicing, but that’s far from the only thing he shares with Kovács. But the hour is late, and Kovács’s permission is expiring. He must return to his prison camp.

“You can find your own way back,” the father says. “I trust you.”

A few more vodka toasts and off Kovács goes, into the late-night empty streets. A half hour later, he realizes he is lost, and there is no one to ask for directions. Down a lane, he spots a building with a light on where he rings the doorbell.

A woman appears in the doorway. She’s sleepy and wearing only a nightgown. Kovács explains that he needs to get back to Camp 6. She tells him—“poor dear!”—he’s much too far in the wrong direction, and that he should come in and stay the night, to catch the first train in the morning—a courtesy Kovács would never have asked for himself.

He is led into a large darkened dormitory, where he senses that others are also sleeping. Exhausted and still a little drunk, he lays gratefully down to sleep. Not long after, he is awoken by a hand on his leg. The hand ranges over his lower parts and then circles ever closer to his sex. Then, in the dark, the owner of the hand quietly crawls into bed, and without preamble or fanfare proceeds to use Imré for her sexual satisfaction.

The act completed, the woman disappears back to her bed, and Kovács falls asleep. But not for long, as he realizes the neighbor to his left has now inched into bed with him for her sexual satisfaction. And then a third female. And a fourth.

At the sixth, Kovács writes, he is exhausted. Dawn reveals the trap he had landed in: an institution for young women!

As for Natacha, a series of unfortunate events conspire against Kovács’s plans to emigrate to the USSR to be with her, and by treachery and bad luck, he also loses the messenger he had been using to communicate with her from his prison camp. In the manuscript, it isn’t long before, without much explanation, his liberation is announced. He prepares his return to Makó, not knowing what he will find there. But before he does, he has one final goodbye with Natacha, who runs to embrace him on the train platform. The steel wheels scream into motion, carrying him away from his first true love. Imré cries, knowing he will never see her again.

The first person to dispute the veracity of Imré Kovács’s published account was László Karsai, a professor of history at the University of Szeged and a respected scholar of the Hungarian Holocaust. In 2007, having read an interview with Imré’s son Serge about the memoir, Karsai got hold of the French text and issued a scathing denunciation titled “‘Avenger’ or Liar?” Citing multiple examples of impossibilities, near impossibilities, and historical inaccuracies in the tale, Karsai took greatest offense at the anecdote of the shrunken member in the SS recruitment office. “If [Kovács] had written that the [SS] doctor was tired or that he never looked at the foreskin, perhaps it would have been a more believable version of this episode,” he wrote, before bashing one of the mysterious meetings with a Zionist agent as wishful thinking. With barely veiled sarcasm, Karsai called Le Vengeur an “incredibly interesting, but also very special memoir” that reminded him of Winston Churchill’s famous aphorism: “In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.”

I decided to visit Karsai in Budapest. Under the reactionary populism of authoritarian nationalist Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, the Holocaust, and Hungary’s role in it, had lately been a subject for debate. Were the Hungarians victims or perpetrators? Who knew what when? A pair of Holocaust museums, one state-sponsored and delayed, the other private, presented competing narratives of the war. The right wing wanted to whitewash the past. The left wanted Hungary to formally face up to it. The battle was best encapsulated in a monument, erected in Budapest’s Freedom Square one night under Orbán, made of a bronze statue of the angel Gabriel, Hungary’s guardian, being tormented by a rapacious eagle, representing Nazi Germany. The inscription above it reads “Memorial for the Victims of German Occupation”—meaning the innocent Hungarians, duped by the Nazis into killing their countrymen, an interpretation that Jewish groups, many Hungarians, and the State of Israel dispute. This explained some of Karsai’s vehemence, and perhaps his lack of sympathy for Serge.

Karsai was willing to show me his research in person, so now, with him as guide and translator, we drove southeast across plains checkered in dormant potato and wheat fields, and yet-to-bloom orchards of peach, apple, and apricot, and on through garlic and onions. Armed with a notarized letter of permission from Serge Kovács, we headed to Imré Kovács’s home region to see if any documentation existed to support the published claims in Le Vengeur. A young Kovács had crossed these same plains, under very different circumstances, six decades before.

At a branch of the Hungarian National Archives in Szeged, in a room down a long darkened corridor decorated with historical maps of Greater Hungary, a librarian showed Karsai and me an official record of Imré Kovács’s birth. It was on the bottom line of page 121 of a frayed blue register labeled “Makó, birth certificates, 1924-1926” and it confirmed he was born in 1926 to a 48-year-old father and 37-year-old mother. Companion documents supported the claim that Imré’s father was a veteran of the First World War and noted official name changes as the family went from Kohn to Kovács to Kohn-Kovács.

Some 50 kilometers away, at the county archives in Makó, a kindly former high school teacher named Zsolt Urbancsok pulled, copied, and stamped what records there were of Imré’s participation in local society before the war. Documents listed his places of residency and his family’s modest personal effects. A police record described how Imré was arrested on April 22, 1944, together with his sister Margit, fined and detained for refusing to wear a yellow star identifying him as Jewish. Urbanscok said the behavior was unusual: Most Jews would have either tried to hide their religion or would have worn the star. To openly defy the order, as he seems to think Imré and Margit did, would have been a dangerous bit of theater. Indeed, Margit, unable to pay the fine, is “taken away to an unknown place,” the local police chief noted, because she “belonged to the Jewish race.” Why Imré was spared isn’t known.

Makó was the center of a thriving allium agriculture that supported a substantial Jewish bourgeoisie before the war. The archivist had written a history of the local Jews, published in Hungarian: a compendium of all that was lost, pieced together from the fragments he watches over from his third-floor municipal office in a former imperial military garrison.

I asked Urbancsok, from what he knew of the history of Makó, could someone like Imré have infiltrated the SS?

“I don’t know,” he said, taking in a breath. “I don’t know the family, I don’t know the circumstances. I can’t answer. It may be possible. Maybe it is absolutely not.”

During the war, Jewish families across Europe were deported, separated, killed, liberated, or hidden, and there was often no way of knowing what had become of them. Survival rates among rural Jews were particularly low. In daily life, dread commingled with expectation, inquiry, euphoria, and false hope. The not knowing was sometimes worse than the news of death. There was little incentive to try to start life over as it was. Return was impossible; home, obliterated.

Before his own wartime odyssey, Kovács had seen his sister Klari marry a Protestant and convert to Christianity. She could still be alive, he realizes in his manuscript—maybe even in Makó. Kovács decides to go there first, as he has no hope of finding any of his Jewish family or friends where he last left them and would at least locate Klari’s husband. In Le Vengeur, Kovács recounts arriving unannounced in the middle of the night, like a revenant. Klari is there, with her kin, alive and well, and overjoyed to see him.

Kovács learns, as he had intuited, that his mother died at Bergen-Belsen. Klari tells him their mother had declared before her deportation, with chilling clairvoyance: “They are taking us away to kill us!” A family that survived the same camp tells Kovács Ilona’s life ended during the Allied liberation bombing, dying not from an ordinance, but out of fear, a heart attack. This makes her a kind of survivor, able to withstand the Germans but just short of fortitude at the cusp of freedom. Did Imré convince himself that such a woman as his mother could not have died of anything less noble than fear—typhus perhaps, so cruel and indiscriminate, or dysentery, or hunger? Her Yad Vashem file, which was submitted in 1993 by her granddaughter Natalia, says bluntly that she was “murdered in the Shoah,” at the age of 52 in Bergen-Belsen, in July of 1944—but even this comes with an institutional disclaimer about the mystery of individual fates:

During the Shoah, Jews were murdered in a variety of ways, among them gassing, shooting, burning, drowning or burial alive, exhaustion through forced labor, starvation, epidemic diseases, deprivation of medical care and minimal hygienic conditions, and more. Some Jews took their own lives in order to escape arrest and further persecution, or to end their hopeless, relentless suffering.

As accessible as the Yad Vashem file is—thanks to the work of thousands of scholars, historians, volunteers, relatives, and witnesses, and the State of Israel—it’s still, on the level of lives like Ilona Kohn-Kovács’s, just the officializing of hearsay. Serge told me a legend that somehow took root that Ilona, being too beautiful, was taken under the wing of an enamored German SS who sequestered her to an anonymous long life in postwar Germany. In Kovács’s version of events, the Red Cross claims his older sister, Margit, is also alive somewhere. And Kovács himself brings news of other prisoners he was with, and through these networks and accounts, people like Kovács tried to piece the events back together, to understand who was gone, here, murdered, lost.

Few of those narratives were linear, sensible, self-contained. They were shrouded by guilt and silence. Most were marked by inexplicable luck or unpredictable intrusions of power: forced out of homes, forced out of the ghetto, separated, forced into labor, forced to sell everything or abandon it, forced to flee just to stay alive. Which of these versions of survival or death is less or more credible than the other?

Back in Budapest after our rural excursion, László Karsai reaffirmed his “100 percent” belief that Imré Kovács could not have been in the SS. He was sipping a fragrant onion soup in a renovated Soviet-era cinema. The capital was humming with Christmas shoppers and smelled of mulled wine and ozone from the electric tram lines. For 600 years, the city had barely had a chance to tidy up before the next revolution or conquest or war had altered its landscape.

Other Hungarian Jews produced memoirs of the Holocaust that didn’t embellish where they lacked information, Karsai said, citing Nicolas Roth’s lucid Avoir 16 ans à Auschwitz (To be sixteen years old in Auschwitz), which appeared in French in 2011 and was presented as the work of a man with an “exceptional memory.” Truthful memoirs aren’t catalogues of heroism and don’t shy away from the worst, Karsai said, citing the example of another Hungarian memoir that unflinchingly describes a prisoner facing the dire choice of partaking in cannibalism or dying from hunger, and choosing the former. Kovács, on the other hand, seems to meet only beautiful women.

“There are a lot of documents about Zionist resistance movements everywhere in Europe, from Istanbul to Stockholm via Budapest,” he continued. But in 33 years of scholarship, “I have never seen documentation of this huge network of Hungarian-German Zionist resistance. No memoirs from members, no files in the Zionist archives in Jerusalem.” If I could somehow bring him a piece of paper from the German Bundesarchiv (Federal Archive) with Imré Kovács’s name and SS recruitment age on it, he’d tip his hat. Karsai insisted that it was impossible for someone’s penis to shrink enough out of fear to not be noticed by a military physician. And yet it is possible, true even, he said, that members of the Arrow Cross threw dead or dying Jews into the Danube.

“Even I can imagine that he was in the SS,” Karsai said, allowing for the war’s insanity. “But not also working for the Zionist resistance.” That, somehow, was too much.

I saw no bridge across this valley of historical memory.

“So why did Imré feel the need to lie, if he did, to make it more amazing than it already was?” I asked.

Karsai put down his spoon. “He hadn’t suffered enough,” he offered. Then he ventured that Imré’s son Serge, the journalist, had either written the whole thing or filled in parts to make it attractive to publishers. Karsai enumerated his evidence. Serge had a motive: He needed money. He had an accomplice: Ploquin. And his actions broke apart his own family, with fights over greed and deception.

Did Karsai have any other examples of survivors’ stories being retold or embellished for them by their children?

“No,” he said. “But why not? This will be a first.”

Later, by email, the Hungarian military archives confirmed there is no record of Mátyás Gajdács, or any of the aliases known to Imré Kovács, having enlisted in the 26th Waffen-SS. Krisztián Ungváry, a leading historian of the SS, went further, saying that there aren’t even any known recruitment directories for the division. The 2nd Hungarian SS barely had time to organize itself, let alone arm. It was made up of mostly paper conscripts and remained a “collection basin for quitters,” he said. From the whole of the European theater, he knew of one single case of a Jew hiding in the SS: the Yugoslav Vladislav Rothbart, who seems to have joined a Hunyadi SS column in their chaotic 1945 retreat from the Eastern Front, but not on the line.

As for the so-called Zionist resistance, it existed. But in Hungary, with the breathtaking speed with which events unfolded there in late 1944 through the summer of 1945, there would have been little time to react and organize. Jews did defy the genocide—in some cases buying time with the approach of the Soviets—using negotiation, bribery, and document forgery, as well as hiding and assisting refugees. But everything about the resistance was complex. The most famous Hungarian case is that of Rudolph Kastner, who negotiated with Adolf Eichmann to allow 1,684 Jews to avoid Auschwitz and instead leave for Switzerland on what became known as the Kastner train, in exchange for money, gold, and diamonds—and, perhaps, his silence about the 12,000 Hungarian Jews a day being sent off to the gas chambers. In Israel, after the war, Kastner was accused of collaborating with the Nazis and was later assassinated by avenging right-wing Zionists. At the same time, many of the people saved by the train went on to lives of consequence. There is also one known photo of a youthful Jewish Zionist resister named Endre Grózs (later known as David Gur) wearing an official full black-leather Arrow Cross uniform in disguise, looking very much like Imré might have in the photo-booth snap of him dressed as an SS.

Which of these versions of survival or death is less or more credible than the other?

István Deák, the eminent 91-year-old Hungarian-American Jewish historian who was born the same year as Imré Kovács and lived through the war in Hungary, told me that, though he deferred to Karsai, he thought it “conceivable but not likely” that Kovács could have enlisted in the 2nd Hungarian SS Division. The conditions at the end of the war were chaotic enough, and the 2nd SS ragged enough, that it isn’t impossible. But, he asked, was Kovács circumcised? I told him the story of Imré’s shrinking member. “That complicates it,” he said. Plus, his neighbors would have known him as a Jew. Like Karsai, Deák wondered how Kovács, an able-bodied 18-year-old, avoided being conscripted into the Hungarian “labor service” battalions required of all “politically unreliable” Jewish men—where Deák himself (in one of the many cruel ironies of the period) avoided deportation to the concentration camps.

“Just imagine the total confusion,” Deák said, recalling his personal experience of Hungary in late 1944 and trying to empathize with Kovács. “A big mass of people moving very uncertainly to the west. The 2nd Hungarian Division was totally untrained and unequipped, a bunch of poor kids with unenthusiastic officers, drafted, living in schoolhouses, doing nothing.”

Why did he think Karsai was so adamant in his incredulity?

“I guess he didn’t experience it,” Deák said. The war made many impossible-seeming things real. “It’s difficult. What do you do? Everything was a risk. One tried this and that, looking for a solution for how to survive.”

One of the most intriguing and troubling episodes in Le Vengeur takes place around Makó. In the book, the war has been over for a year, but the lost and scattered are only just starting to return to see what’s become of their shattered past and fragile future. Kovács himself wends his way to his village from the Soviet POW camp in Odessa, in the company of a fellow Makó native named Jeno Davidovitch.

Now that the war and his imprisonment are over, Imré prepares to depart for Palestine. Unlikely to ever return to the region that destroyed his loved ones, his sister Klari suggests he visit with the relatives he has left in Hungary. He travels to Mezőtúr, some 100 kilometers north of Makó, to see his paternal aunt and uncle. Aunt Pirike is 35, one of few survivors of the deportations. Imré’s uncle, Pirike’s brother, is away selling livestock, together with the uncle’s wife and Pirike’s husband—the extended family lives under one roof. So Imré finds himself alone in the house with his aunt and a maid.

Imré and Pirike stay up late in her rough country kitchen in rural Hungary, 1946, talking by candlelight about their experiences during the war: she of her terrifying deportation and miraculous survival, he of his journeys and suffering.

The hour grows late, but after years apart, the pair still have much to tell each other. Pirike invites Imré into her chamber—to keep from disturbing the maid, she says—and asks the 20-year-old to sit on the bed with her.

In his naïve prose, Kovács explains how the formerly modest Jewish women like Pirike had since the end of the war cast off their strict upbringings and thought only of enjoyment—to forget the gas chambers, the camps, and death. “You see, Imré, you and I are some of the rare Jews who were lucky enough to escape this war,” she says. “Now we must enjoy life.” Young Imré senses the true meaning of her words, as he allows himself to be seduced.

Later, Pirike tells Imré not to worry: If she gets pregnant, she promises to take responsibility for the child. Her husband is selfish and a bad lover, she says—worse, he’s infertile, and Pirike wants children. No, it’s an obligation to replenish the Jewish population, she explains. The incestuous affair continues a few weeks, until Imré seduces a neighboring farmer’s daughter, which sends Pirike into fits of jealousy. The odd domestic idyll turns sour, poisoned by accusations and threats. The uncle, who had delighted in discovering Imré alive, kicks his nephew out of the house. Imré is happy to go anyway: He is headed for Palestine.

According to a footnote added by Serge Kovács in the 2006 publication, a child was born of this incestuous union, and turned over to the maid, to be raised elsewhere. Imré allegedly searched for this lost son in vain—a man who may still be alive, in his early 70s, perhaps in Budapest, ignorant of his extraordinary postwar origins. After the book came out, Serge thought he had found his half-brother, through resemblance, in a famous Hungarian actor. “But who are we,” he said, “to suddenly unsettle a man’s life with the truth?”

In Israel, Imré Kovács is given the codename Asher Cohen, a member of the notoriously disciplined and secretive Zionist paramilitary known as the Stern Gang. Later, Kovács quits the regular Israeli army after a series of disappointing combat experiences in the Golan Heights but then is persuaded to attend officer training instead. Meanwhile, his sister Margit, living in Haifa, introduces Kovács to a dark-haired Hungarian beauty named Martha Weiss, whom he thinks of marrying, until he meets Martha’s friend Esther. All three of the women become infuriated with him for his dalliances. Between more battles and training near the Syrian border, he has another amorous adventure, this time with a married woman, who, at an ultimatum, chooses her husband and son over Imré—a wounding of his pride that leads him to a night of uncharacteristic heavy drinking, which leads him to meet, by chance, with Yair, who informs Imré about the Nakam, also known as The Avengers, a group of former partisans who had organized to retaliate for Jewish death through methodical assassinations of Nazis.

It’s 1953. The war in Israel is over and things appear calm. Yair hooks Kovács up at a Haifa nightclub called The Piccadilly with a representative of The Avengers. Many of the highest-level Nazis have fled to Latin America with their stolen hordes and can’t be tracked, the contact explains. But thousands of the lower-level SS have found refuge in the French Foreign Legion.

Engaged in postcolonial struggles in Indochina and Algeria, the Legion, lacking for men, had recruited in the wreckage of the war, where identity was as fluid as a new set of papers. By some estimates, certain units of the Foreign Legion comprised nearly 45 percent soldiers of German origin. The legion was known to prefer personnel with military experience in their home country—as long as the identification they offered didn’t appear on an Interpol list, they were in. Yair’s contact had a role for Kovács because Imré was 27—most of the secret group’s members were already older than the recruitment age limit of 35. Would Kovács consider enlisting in France to hunt Nazis?

Three weeks and one Piccadilly waitress later, Imré Kovács is the owner of a fresh passport and a one-way boat passage from Tel Aviv to Marseille. Recruitment there goes off without a hitch: France is desperate for reinforcements in Southeast Asia. Kovács, now legionnaire 61-750, signs a five-year contract with minimum two years in Indochina. He is shipped to Algeria for basic training, and after revealing his elite sharpshooting skills (acquired as an SS trainee in Austria), he is promoted in rank. He maintains contact with Yair through encoded post.

On base leave, a few weeks later, he discovers his first Nazi, a German going by the name of Pischler who refuses to eat at a Jewish-owned bistro and, a few beers in, openly longs for the Führer. Kovács eggs him on by admitting to being a former SS himself. Pischler, delighted, boasts of his murderous career in great detail, describing massacres in Warsaw and regretting only that the Soviets arrived too soon to allow him to liquidate more Jews. “One day,” he brags, “when this story is written, you’ll hear about a Müller … and that’s me.” Müller is on the secret list of Nazis to hunt down, compiled with the help of moles at the Nuremberg trials. Kovács sends word to Yair. At the next roll call following another base leave, Pischler/Müller is missing and never heard from again.

On the 28-day passage to Saigon, Kovács is discovered by a co-conspirator, an officer also engaged in the anti-Nazi cause. They make an alliance. At a screening of an American World War II film, a German by the name of Weber begins to complain to Kovács of the failure of the Reich to exterminate all Jews. Weber has joined the French Foreign Legion because he is wanted by the Americans “and all those dirty Jews.” He boasts of overseeing the death of 30,000 Jews in and around Kiev, claiming to have made them dig their own graves before massacring them on the spot because there was neither time nor resources to get them to the concentration camps. Kovács contemplates this horror while leaning on the ship’s rail and watching dolphins play in the wake. He unburdens himself to his new ally, who sympathizes and promises to take care of Weber.

The next day, the cry comes: “Man overboard!” Two hours’ search comes up empty. All hands on deck to identify the missing soldier: It’s Weber.

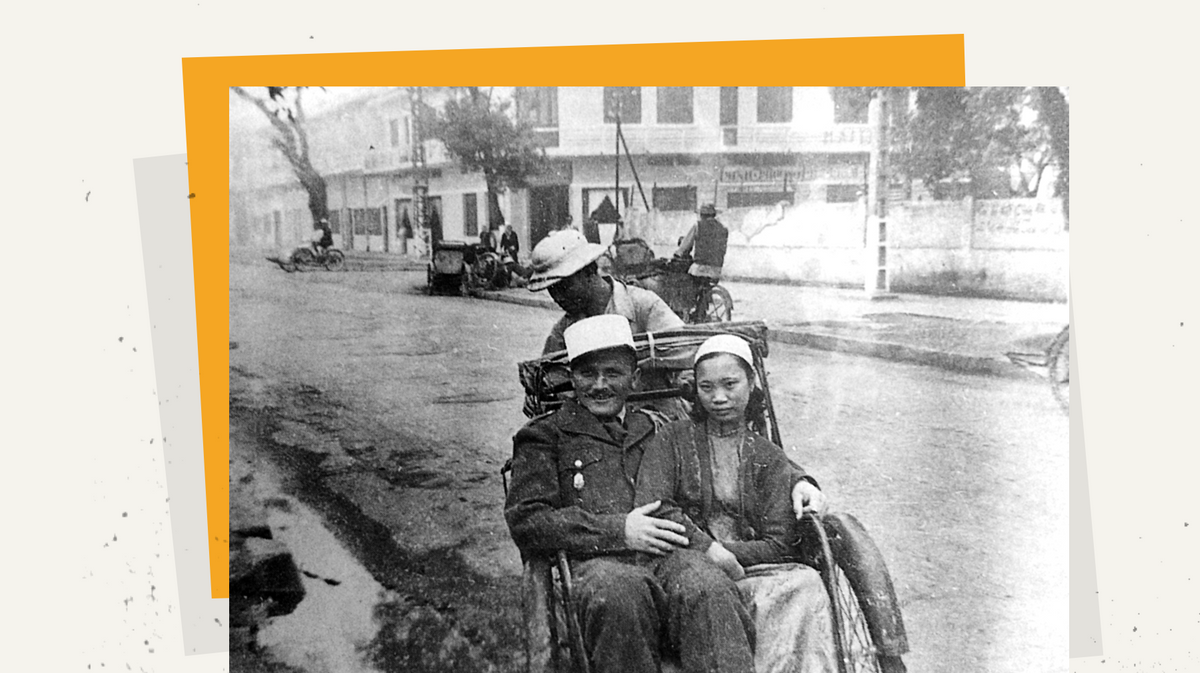

Once in Asia, Kovács’s camp is destroyed by typhoon. He enjoys a Vietnamese massage parlor, meets a Jewish-Hungarian madam at a brothel and takes another “taxi-girl” home (a photo in the book shows him grinning in a rickshaw with a Vietnamese woman on his lap), patrols the jungle, takes grenade shrapnel in his hand, and avoids death with the timely arrival of reinforcements. In convalescence in Haiphong, he takes up dynamite fishing. When he finds the dog tags of dead German legionnaires he can cross off his secret list, he thanks the “Viets” under his breath for doing the job for him.

Through the spring of 1954, Kovács fights at Dien Bien Phu, is taken prisoner, is released in an exchange associated with the Geneva peace accords, and participates in the long slow retreat of French forces. What’s left of his brigade is shipped to Algeria, their morale at a nadir. In the Suez Canal, 26 men jump ship, escaping into the desert and an unknown fate. Among them are two former Nazis.

Once in Algiers, things don’t improve much. Kovács is engaged in the cruel and ill-fated struggle against the guerrillas of Algeria’s National Liberation Front. In rocky Berber outposts, he narrowly avoids death, sees many comrades die, and, worst of all, watches one of his own companions sadistically torture a suspected militant. Desertion, theft, brutality, cruelty, senseless death—Kovács has had enough. He decides to quit the Foreign Legion, no matter the cost.

It is May of 1956. The Second World War recedes into the past. The Cold War rises. Nasser nationalizes the Suez. Rumors flare of an anti-Soviet insurrection brewing in Budapest. But Yair informs Kovács by letter that their work is not done: Many prominent Nazis remain at large in the world, and Paris, capital and crossroads, would see its share. Two months later, Kovács was there.

Discharged from the Foreign Legion, Kovács undergoes psychological and social counseling to prepare his reentry into French civilian life, even though his service does not qualify him for citizenship. He is given a residency permit and paid welfare. After a few false starts, he is connected with a former legionnaire he knew from Dien Bien Phu who sets him up at a hotel restaurant, Kovács’s first paid job since being a stable boy in Makó. But in his telling, Imré prefers to quit rather than rat out a thieving cashier.

Kovács moves on to a larger and more reputable establishment in Paris, where he punches a domineering chef who teased him for his Hungarian accent. When the chef responds by wielding a rolling pin, Kovács knocks him out. Meanwhile, 200 tourists await their meals. The rest of the staff is pleased to see the dictatorial and ill-mannered long-serving cook taken down a rung. When Kovács is fired on the spot—“a waiter is replaceable, but not a chef!”—the rest of the staff go on strike out of solidarity. Either both Kovács and the chef go or neither goes, they demand. The hungry tourists have tickets to Les Folies Bergère, so the owner rehires Kovács and then keeps him on. The bully cook becomes the butt of jokes and loses 40 pounds. Rumor circles back that he had never previously been fired because, as a longtime employee who ran the hotel’s black-market operations during the German occupation, he knew too much.

Kovács is so impressed by the solidarity on display in his defense at the hotel that he decides to live in France. He is 30 years old.

This is where Imré Kovács’s written account leaves off, like a 19th-century novel ending with the heroine’s marriage—in 1961.

But life goes on, beyond the page. Kovács finds a Tunisian-born Jewish bride in a personal ad in Ici Paris and considers that, though plain, she has child-bearing hips, and so will do. His father-in-law helps him purchase the Boulangerie Hongroise, at 5, rue des Blancs-Manteaux, near Les Halles, which he runs until he has a marital crisis and heads south to Cassis to cure his nerves. On his return to Paris, he takes a job at Flambaum, a celebrated Kosher restaurant and banquet hall in Montmartre, near Les Folies Bergère. He bakes Hungarian wedding cakes and charms guests at the front of house, and meets Roger Cazes, who had taken over the Brasserie Lipp from his legendary father, Marcellin. Cazes brings Imré Kovács to Lipp in 1965, and for the next 16 years, that became Kovács’s life.

Why does Kovács survive? It is no coincidence or feat of fitness or guile. God, he writes, has kept him alive.

There, Kovács called himself Monsieur Serge, because his eldest son’s name was easier for his French clients than his own Imré. From Tuesday through Sunday, he labored in his server’s tux and long apron. On Mondays, he tossed some coins and candy at his kids or took them out for a pastry. He had eight Jewish children: Serge; Stéphane; Pierre; Thierry, who died as a newborn; Nathalie; Annie; Esther; and, unexpectedly, Michel. Home was a chaotic free-for-all. Twice, Imré made plans to emigrate, to Australia and Israel, but his wife refused to leave her family in Europe. In the late 1970s, Imré and his wife divorced.

For some 14 years after that, Kovács floated in retirement, living for a few years in the Parisian suburb of Vanves before heading further south to join a former waiter from Lipp in Auxerre, in Burgundy. There, every afternoon, in a small house he bought, he sat down to write what he remembered of his life, chapter by chapter, starting with the sound of his mother’s voice calling out to him for dinner in his Hungarian home village before the war. He then recorded the manuscript on cassette tapes. He approached his son Serge, in journalism school at the time, to see if he had any interest in the project, but Serge declined. Imré’s daughter Nathalie, like any teenager—and like many children of Holocaust survivors—wanted none of her father’s burden.

“My father wanted to talk,” she told me many years later, “but I was not listening.”

Serge connected his father with a girlfriend, who for a fee agreed to type up the tapes. Kovács then approached Jean-Paul Sartre’s postwar journal, Les Temps modernes, to see if the existentialists would be interested in publishing it. Their subject had been the calamity of Europe. Their offices were down the street from Lipp. He was not given the courtesy of a reply. Claude Lanzmann, the French dean of Holocaust memory, director of the nine-hour epic Shoah and a regular at Lipp, sent him packing. Another Lipp habitué, Georges Lambrichs, a celebrated editor at the French publishing house Gallimard, also declined. Eventually, Kovács put the typescript away, and never spoke of it again.

One day in 1995, after a week of living on his son’s couch since selling his house in Auxerre—divorced, sick of France and the French, pining for home, mourning his youngest son, Michel, who had died in Israel the year before, terrified by signs of dementia and unwilling to be taken into supervised care—Imré Kovács took himself to the Gare de l’Est, to board one last train. He rode all the way to Budapest, where he lodged with distant cousins. With the help of a young Hungarian man he met in France, he made his way to the village of Orosháza, a few miles from his hometown of Makó, the onion capital of Hungary. With his savings, he bought a modest house on Csabai Street, large enough for visitors.

Alone there, tending roses, visiting the market, losing his grip on reality, he spent his days waiting for the end. He crashed his car, had his license revoked. Simple things like a bottle of perfume would send him into a paranoid rage. When his adult children visited, he believed they had come to poison him. Then he would calm down and wake up the next day with no recollection of the drama.

For many Jewish survivors, the simple act of living could be hard. Imré’s sister Margit, for example: No one knows how she endured her deportation to Auschwitz. Serge told me of an unconfirmed family belief she may have been raped by an SS officer; when she miscarried, she was experimented on like a lab rat. She eventually landed in Palestine and lived in Haifa, marrying, divorcing, remarrying, divorcing again, but never able to have children.

Nathalie recalled Margit carrying an elegant small handbag that had nothing in it and living in a cockroach-infested apartment there—a confused, lonely woman. Eventually, as Serge put it, “she lost it” and was taken into the care of the Jewish state. She died in 2005, at age 85, and was buried as Margot Kovich in Kiryat Ti’von.

Her sister Klari, who survived the war because she had married a Protestant, lived a simple, rural life in the town of Baja, Hungary, on the banks of the Danube. In the 1960s, Klari renewed her relationship with Imré, and the siblings saw each other when they could. Her children called their uncle Imré bájos, “lovely Imré.” But brother and sister no longer understood each other the way they had before the war.

In 1986, at Imré’s urging, Nathalie organized an encounter between Klari and Margit in Haifa, at the old-age home where Margit was living. The two sisters had not seen each other in 40 years. Unprepared for the depth of feeling, shocked Margit was full of bitter recriminations: Klari had escaped the atrocities Margit had endured. The hoped-for loving reunion instead was a tearful, befuddling disaster. The sisters never reconciled.

I thought of Primo Levi’s painful introspection in The Drowned and the Saved when he comes to the appalling realization that the good were more likely to die in the camps than the “the worst … the selfish, the violent, the insensitive, the collaborators of the ‘gray zone,’ the spies.” To be alive after the calamity was to be counted among those worst. It meant carrying the incomparable guilt of having taken the place of another, perhaps better, human being, who might have had greater purpose in life—and yet to be entirely blameless at the same time.

The cemetery where Imré Kovács is buried sits behind a squat white ceremonial hall with a pair of arched windows. Clipped pines and skeletal fruit trees line the street off the main entrance to Orosháza, and single-story houses under ceramic-tile roofs mutely observe anyone who approaches—which is essentially no one, as the Jewish population of Orosháza, once thriving, is gone. On the day I visited, low grayed-out clouds, like breath mist, dulled the sky.

Nándor Berger, the 68-year-old volunteer who for about $30 a month cared for Orosháza’s Jewish cemetery, stood at the gate. I was the first foreigner since Serge himself to arrive here, he said. He wore a ragged black jacket and a black knit cap in the humid cold, accented by tufts of black hairs in his ears. Though not Jewish himself, he expressed a sad admiration for Jews, whoever he imagined them to be, saying, like a great guilty sigh from his people, “It’s not easy to fulfill the obligations of Jewish life.”

Inside, overgrown and derelict, the cemetery was a tangle of ivy and stone. A passenger train rumbled by along a track laid on a dike, the same tracks that carried Jews by the thousands to their deaths. A monument to locals killed and deported from 1944 to 1945 listed hundreds of names: Sarolta Gelbermann, Magdolna Preisz, Emil Grossman, Jakab Klein, Endre Altmann, too many whose final resting place is unknown.

Down a central alley, between Imré Klein and Lászlóné Singer, is KOHN-KOVÁCS IMRÉ, as his gray tombstone reads. His grave was tidy compared to others, despite the weeds pushing through cracks in the cement walkway. Berger pointed to it and shrugged, before showing us around some of the other corners of the plot, where 1944 and 1945 appear more often than they should.

A few blocks away, Erzsébet Boldog was excited to share the walnuts she had collected from the tree in her courtyard. She was living in a single room of what was once her parents’ house, because it was all she could afford to heat. There was a single bed, a television, a table with a vase of carnations, some hunting trophies on the wall including a gaping fishbone maw and a skittish tabby cat outside. Her son József Attila Boldog would call her every day from Northern Ireland, from the truck he drove there. He left Orosháza, the Boldogs’ native village, at the age of 18, with a visa to emigrate to Australia, but went instead to France, then Italy, then Israel, after rediscovering his Jewish roots. He is what Western Europe calls an economic migrant from Hungary on generous days and a refugee on harsher ones. Boldog, widowed for years, plied her visitors with snacks and peach nectar.

“Imré,” she said, was a “very decent” older gentleman, “a very handsome man,” who lodged with her for a year and then bought a house nearby. Kovács landed here because of his friendship with her son, who thought the village might please him, so close to his boyhood home of Makó. “All Hungarians are the same,” she told me through a translator. “When they get to be older, they want to come home.”

“Did he ever talk about the war?” I asked. “Did you ever hear of a manuscript about his life?”

“No, never,” she said.

“Did he own a typewriter?”

“Yes,” she said. “He had one, an old machine.” Later she said, “He was a very good storyteller.”

Awash in Le Vengeur’s far-fetched descriptions of gallantry, I wondered out loud if my hostess had fallen for Imré’s romantic wiles. From photos his sharp features were still dashing under his cap, even in his old age. And after spending so much time in his fabricated world, I wanted him to have found love. This charming, attractive widow, who swelled with heartfelt affection for him, seemed a perfect match. I pictured Imré tending his roses under her appreciative gaze.

But naturally I had it wrong. “During his last years,” Boldog said with a hint of bitterness, “a gypsy lady moved into the house with him. Her name was Ilona Rácz. She was present during his funeral, and he even bought a house for her. This 28-year-young lady,” she tsked, “she took a lot of money from old Imré.”

So Imré had seduced a woman again, in real life. Or Ilona Rácz had seduced him. His last conquest, half his age but unable to resist him. In truth, she was using him. It was no coincidence that she shared Imré’s mother’s name, the mother he lost in the Holocaust, a murder never forgiven and the driving force of his life. Boldog didn’t like the “gypsy lady,” who she said took everything Imré had and left him to die.

But did he like her? I think he might have. Imré’s daughter Nathalie later told me, “My father was a man who loved women.” Serge conceded the same, when, at his spare apartment outside Paris, I asked him about Rácz. “I don’t know if he slept with her,” he said. “But this girl, even if she exploited him, at least she was there to warm his heart.”

Or maybe she wasn’t. In the end, Boldog said, “Imré was totally alone.”

If he were alive, we could ask Imré if what he’d written was a fantasy, a novelization or as true an account as he could muster. The freedom to fictionalize is after all one of the great luxuries of life—to invent stories, sometimes about yourself. The Holocaust imposed its narrative on Imré and his family; his defiance was to insist otherwise. Maybe in reality he was so wracked by guilt at having survived or had done something so low and debased to have gained that survival that the only way for him to repair the damage was to imagine himself infiltrating the Waffen-SS and hunting down his mother’s killers. Maybe he was inspired by the fantastical world of Brasserie Lipp. It’s hard to know where the real blurred into the imagined. Or maybe it was all just as he said.

“I think we all have secrets,” Nathalie told me. “We all have things that we are proud of. We all have things that we are not proud of. Knowing my father, I suspect that many things in his story are true. Some things have probably been a little bit twisted, but on the basis of true situations. You understand what I’m saying?”

So here are the facts: Imré Kovács was born. He survived the war. He traveled to Palestine and became a legionnaire. He lived in France, where he worked as a waiter chez Lipp, and died in Hungary. A story that was written down in typescript was attributed to him after his death, and published in French. In the Holocaust, millions of Jews died, including Imré’s mother.

Imré Kohn-Kovács is buried in a derelict Jewish cemetery in Orosháza, under the sign of the priestly blessing of the kohanim. That his experience was heroic in some ways, and not in others, is impossible to doubt.

Matthew Fishbane is Creative Director at Tablet magazine.