In Memory of Milan Kundera

On the passing of the great Czech writer and dissident

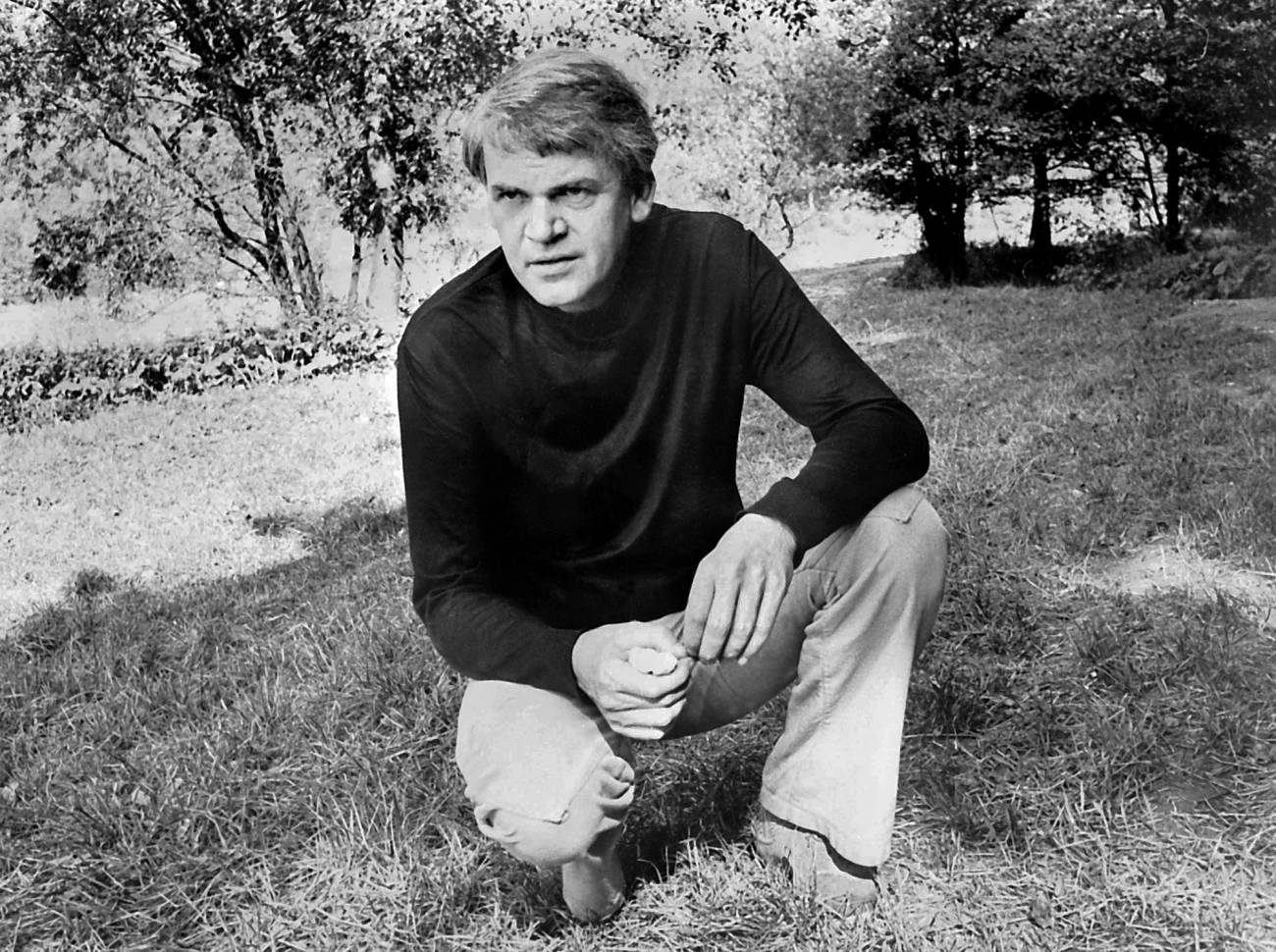

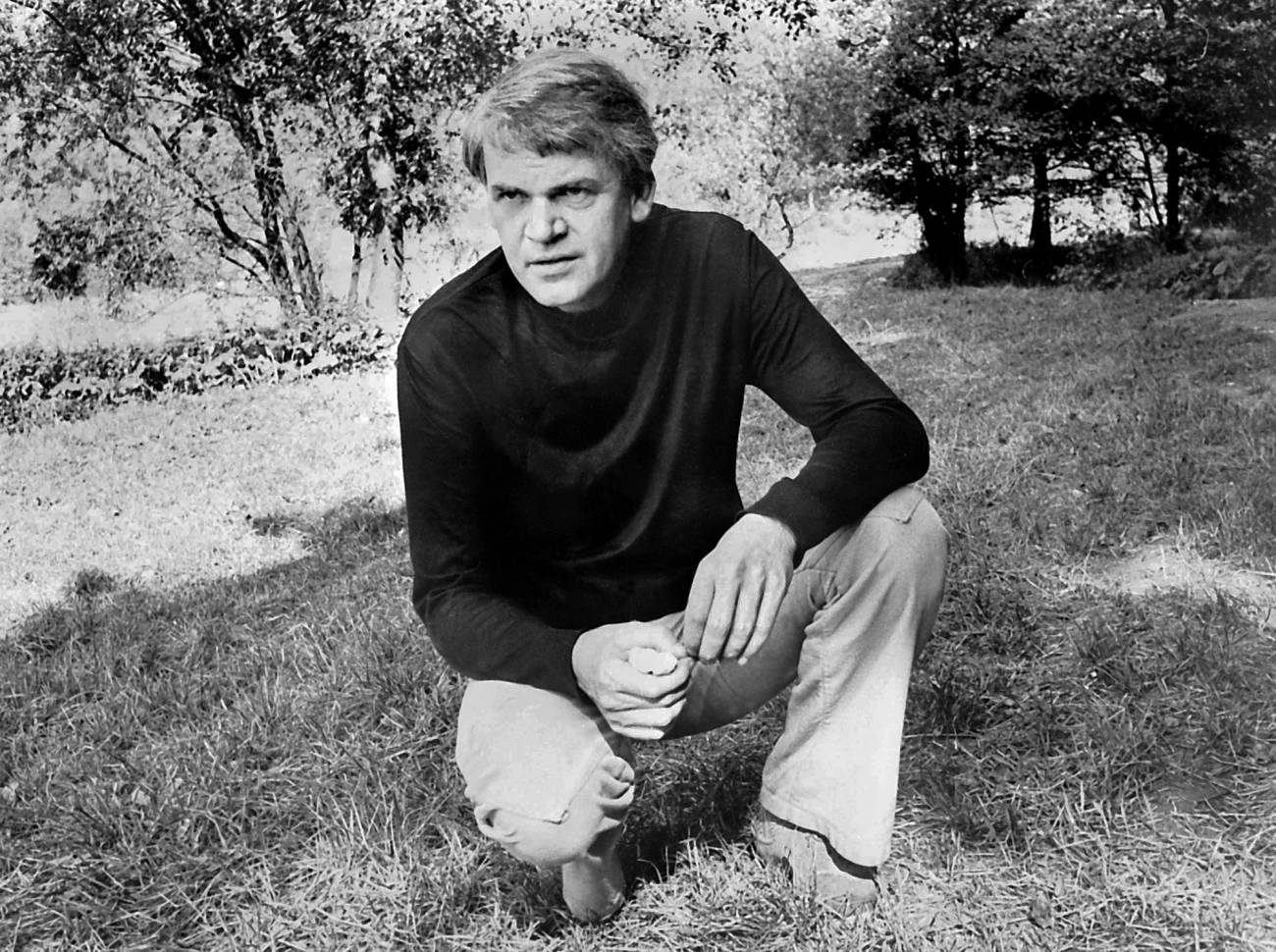

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

In the spring of 1993, I was working at the Slavonic Library in Prague with the remains of the rich collections of the former RZIA (Russian Historical Archive Abroad), which the Soviet liberators had pillaged back in 1945. Every day I would take a long lunch break and wander around the old city, stopping now at a wine bar, now at a secondhand bookstore. Once, in the middle of May, I came upon a copy of Milan Kundera’s 1961 poetry collection, Poslední máj (The Last May). The title of Kundera’s collection was a doleful homage to the long romantic (and to some, Byronic) poem “Máj” by Karel Hynek Mácha, an icon of Czech national culture then bursting through the Habsburg seams. But Kundera’s title could also be read as a gesture of melancholy—mourning the Prague Spring and the parting with the poet’s homeland—well in advance of 1968 and the Soviet tanks rolling through the streets of the city of Golem.

Kundera’s collection was inscribed to an unknown Czech lady—almost like a Prague-set novella that Stefan Zweig had forgotten to write. I purchased the volume, and it now occupies a place of honor in my rare books collection alongside the Nabokovs and Bunins and the other spoils of expatriate writing from Eastern and Central Europe. As I think of Milan Kundera’s passing in Paris at the age of 94, I remember my first encounter with his work back when I was a 19-year-old Moscow refusenik, and the shock of discovering that such a literary sensibility could actually emerge directly from the Soviet system.

In June and July of 1986, I participated in an expedition that took us, a group of university students and faculty, from Moscow across the south of Russia to the Caucasus and the Black Sea. On July 17, 1986, we left the Black Sea and traveled, with an overnight stop somewhere north of Rostov-on-Don, to the eastern corner of Voronezh province. Throughout the expedition we would spend long hours on the bus, especially when we were making blitz drives between major sites. For instance, between Krasnodar province and Voronezh province we covered over 500 miles. By the standards of Soviet road travel at the time, these were supreme distances. There was only so much sightseeing one could do through dusty or mud-splattered windows. While in transit on the bus, I would chat with my peers and also catch up on sleep and reading. Not surprisingly, given the double life I was living, refusenik affairs were outside the circle of our many hours of conversations on the bus while in transit. I remember this well because of the two forbidden books I was reading during the expedition. One was a wry literary critique of the Soviet bloc, the other a Jewish love story set on the eve of the Shoah. I never got to tell my peers what I was reading; they sensed something forbidden and didn’t ask.

Both books were carefully wrapped in Soviet newsprint, for preservation and to conceal their covers. Both were English translations published in the United States, and the origins of the authors lay within the confines of what in 1986 was still Soviet-controlled space. A visiting American couple had given us these books in Moscow not long before I took them on the road. One was Shosha by Isaac Bashevis Singer, and the novel transported me to pre-World War II Jewish Warsaw. Hasidic Jews were only vaguely known to me at the time, and I must have been reading Singer less as fiction or poetry of imagination and more as history or truth. It was a novel about the destroyed world of East European Jewry. I read Shosha as a 19-year-old refusenik on a bus traversing the plains of southern Russia, without being able to share my impressions; the place and manner of reading made the sense of Jewish loss ever more acute. The other paperback was The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera. I must have since reread the novel 10 times while teaching it to American college students in my course on exile. I’m a 56-year-old immigrant as I write these lines, the Eastern Bloc is no more, Russia is fighting a war against Ukraine, and the novel no longer excites me the way it did when I read it for the first time as an impressionable Soviet student and young poet.

And yet, back in 1986, I read Kundera’s novel as nothing short of the manifesto of an Eastern Bloc artist-intellectual. I felt that Kundera had given his reader a grammar of life in which sexually amoral conduct often stood in for political protest against the totalitarian system. At the time, I could have signed my name under each page describing the thoughts of the main character, the Czech surgeon Tomáš. In many ways Tomáš’ thoughts of the totalitarian world—of love and sex, of art and music, conformism and dissent—were also my thoughts. I could have sworn by Kundera’s book, and yet I couldn’t even share my reaction with anyone around me. I loved the book and suffered from the inability to share my love. And I still love it the way one bitterly loves one’s abandoned, disappeared past.

And so on this July morning in 2023 I whisper: Sleep well, Milan Kundera. May your lightness be bearable, your jokes laughable in the worlds to come.

Maxim D. Shrayer is a bilingual author and a professor at Boston College. He was born in Moscow and emigrated in 1987. His recent books include A Russian Immigrant: Three Novellas and Immigrant Baggage, a memoir. Shrayer’s new collection of poetry, Kinship, will be published in April 2024.