In Praise of Nat Hentoff

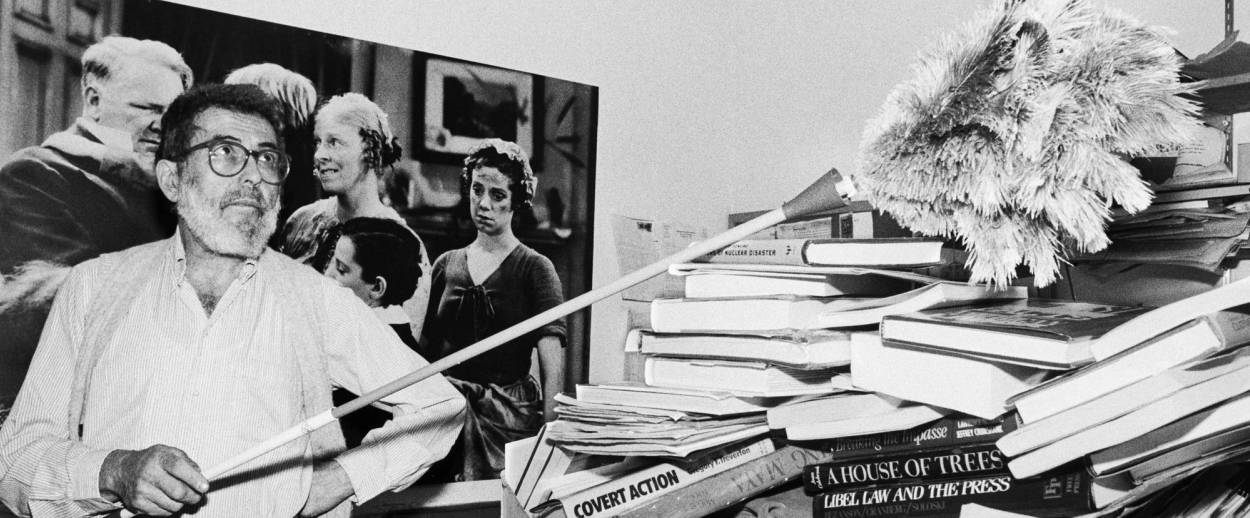

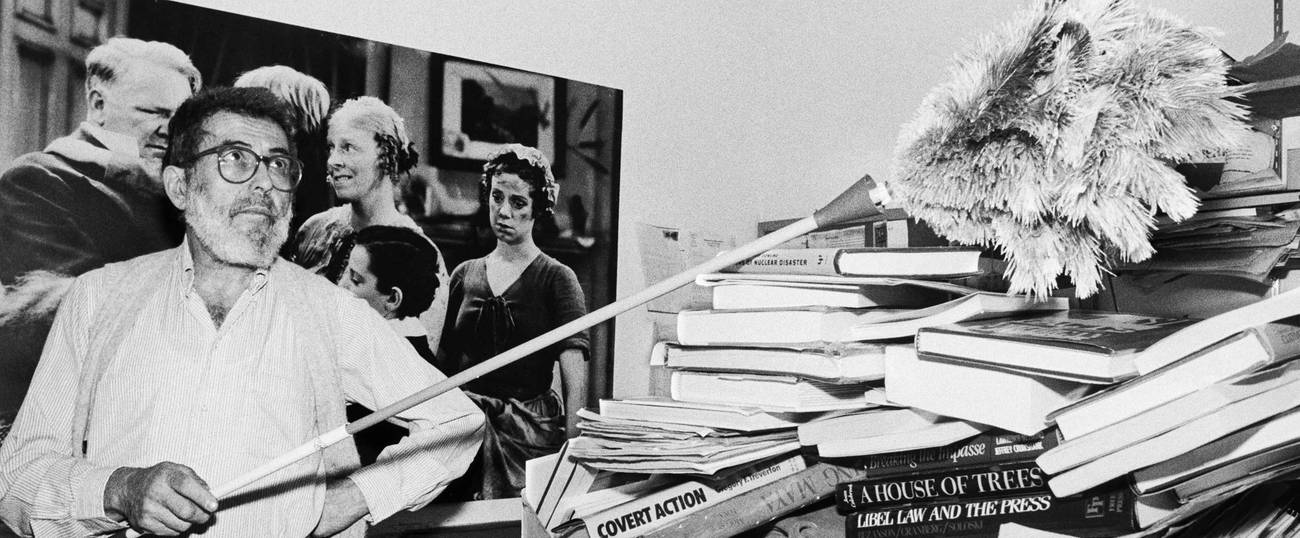

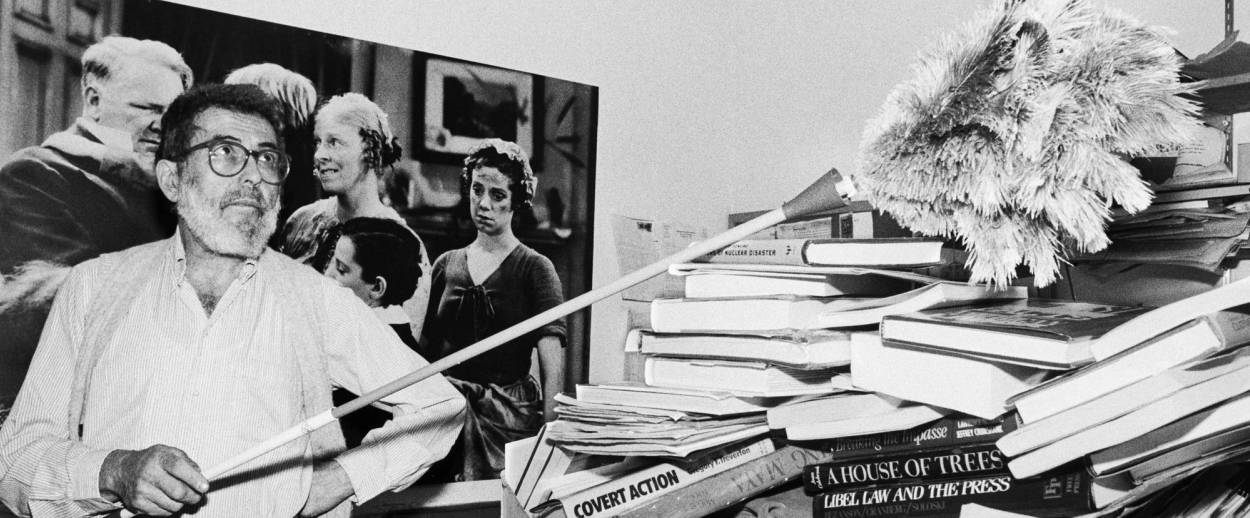

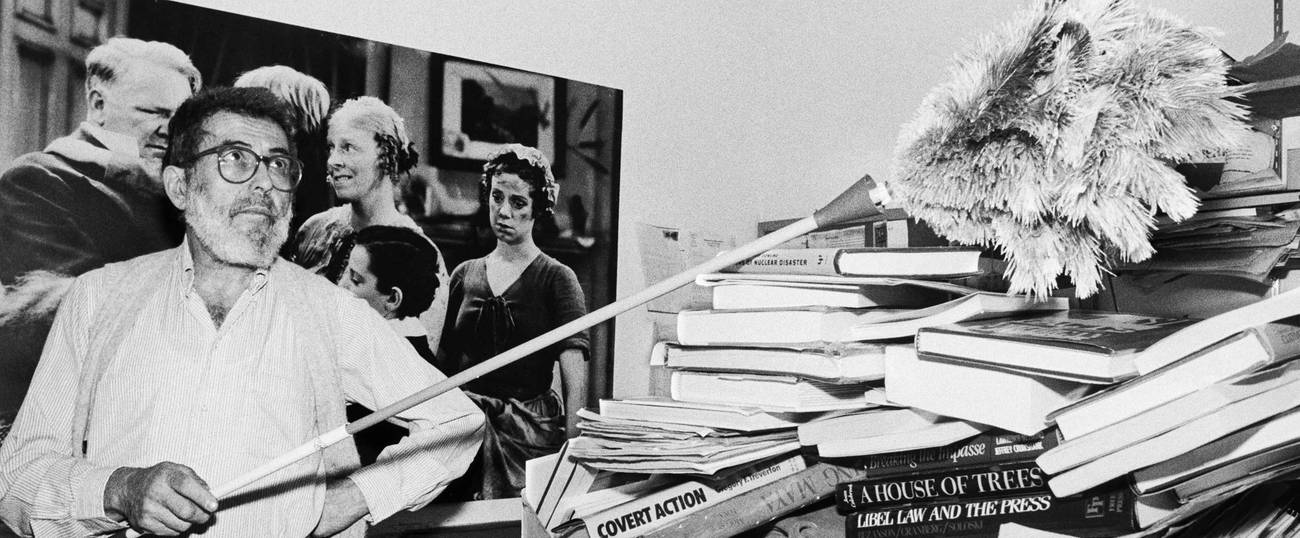

The influential ‘Voice’ critic died Saturday at age 91. His bohemian fearlessness became a popular culture.

It is always said in praise of Nat Hentoff that he radiated integrity, and the unpredictable nature of his opinions added up to a living display of prickly individualism, and it did not really matter if you agreed with him on any given point. You noted his opinion, and you noted the predictable quality of your own opinions, and you felt inspired to stand up a little straighter. Sometimes he was convincing, too. To read him was therefore always beneficial. He improved your opinions, or, if not, he improved your character. In my own case, he improved my journalism. I toiled shoulder to shoulder with him for a dozen years at The Village Voice in the prehistoric era when journalists still had to come into the city room with their copy, which meant that he and I crossed paths twenty times a week. And every time that I appeared to have come under siege from my outraged readers or from some other writer, which was not infrequently, Nat would emit a quiet and appreciative chuckle and continue on his way. He was good for the morale, which made him triply beneficial.

His embodied a certain grandly raffish culture of the past, and this was ultimately his greatest virtue, in my eyes. The Village Voice was founded in 1955 and flourished quietly for ten years or so before everyone discovered that various attitudes and styles from the Voice had taken root on a national scale, and people were reading the Voice in more than a few places around the country, and in some of those places were founding new “alternative” weeklies of their own, on the model of the Voice. That was a marvelous development, and yet, under the pressure of success, something in the presiding spirit at the Voice itself and at some of the other weeklies began to grow a little coarser, without anyone taking note. The coarsening was a product of the transition from the bohemian and downtown non-communist left of the 1950s and early ’60s to the vast and national New Left that followed, which was a mass movement. And it was a product of the transition from the downtown avant-garde to the counterculture of the late ’60s and ’70s and later, which became a popular culture. The older audiences were coteries, the newer ones were publics. The older spirit was anti-conformist, the newer spirit lent itself sometimes to groupthink. Nat remained a man of the older spirit. He expressed it in his unrelenting hardline campaign for free speech. And he expressed it in his memoir Boston Boy, about growing up in knockabout Jewish Boston, persecuted by Irish anti-Semites and admiring the jazz world; and his books on jazz; and his pioneering biography of A.J. Muste, the leftist and pacifist—maybe the biography, especially.

Muste was his hero—Muste, the original great churchman of the 20th-century American left, a Congregationalist minister who somehow ended up a labor leader; then a labor educator; then a Trotskyist; then an appalled ex-Trotskyist; then the leader of a tiny circle of pacifists and leftists who exercised a huge influence on the Civil Rights revolution, in its early stages; and ultimately the principal leader of the mass anti-Vietnam War movement in the mid-’60s. He was, in short, a man of power, capable of shaping the political imagination and actions of masses of Americans—who, ever faithful to his own conscience, never thought of himself as a man of power. He was Edmund Wilson’s leftwing hero, which was fitting, given the cantankerous quality of Wilson’s individualism. And Nat’s admiration of Muste was likewise fitting. It is true that, as the decades wore on, the downtown and intellectual left that revered people like Muste gradually faded, which left Nat feeling a little stranded, I think. But that was to his honor.

At the Voice in its years of greatest glory Nat and Jack Newfield were a magnificent duet, with a third voice in the harmony added by Jules Feiffer. Newfield, the muckraker, knew how to thunder. Every year he labored over his blockbuster articles, the “Ten Worst Landlords,” or the “Ten Worst Judges,” or something of the sort, and he brought an emotion to his exposés; and he took delight when, as a result, some of his targets were dragged away to jail, as did happen from time to time. Feiffer, by contrast, a man of the arts, was (and has remained) unfailingly elegant and wry, as if singing melodic tenor to Newfield’s thundering bass. And Nat sang baritone in the middle, a good prose stylist, always intellectually curious and broad, always wondering out loud, even if he expressed his wonderings in the confident tone of a man who has made up his mind.

I enjoyed watching Nat on the occasion of a birthday celebration of Newfield, at the Village Gate on Bleecker Street. Newfield had turned himself into a power of sorts in the New York City Democratic Party, and a variety of politicians and trade-union people showed up at the Gate to give him an applause, or to stay on his good side. Nat stood at the microphone to deliver his own salutations, and, in the course of his speech, he launched a few sallies at the governor of New York, who happened to be in the audience. This was Mario Cuomo, who listened for a few moments and then, having had enough, walked up to the stage and literally shoved Nat off the platform. It was funny. It was oddly affectionate. Nat seemed surprised to be shoved off. But he also seemed willing to be shoved off, and why not? He was not in the business of maneuvering among the powers-that-be, not in the way Newfield did. He was not someone who could order the State Police to go make arrests, the way Governor Cuomo could do. He was a man who spoke his mind—to Cuomo’s face, if need be, or to anyone’s face—and he could dish it out, and he could take it, too. So he took it, and in a good spirit he returned to his seat, and he appeared to be splendidly and appealingly pleased with himself.

***

To read more of Paul Berman’s political and cultural criticism for Tablet, subscribe to our print magazine.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.