Innocents Abroad

Jerry Herman’s musical ode to the land of milk and honey

It was in a Manhattan grocery store that Jerry Herman, the composer and lyricist behind such musical megahits as Hello, Dolly! and La Cage aux Folles, felt his first jolt of success. The year was 1961 and Herman, then 30 years old, was shopping with his friend, the actor Charles Nelson Reilly. As Reilly tells it in Words and Music by Jerry Herman, a documentary by Amber Edwards slated to premiere on PBS on January 1, they both started screaming the moment they realized what was pouring out of the store’s Muzak system: “Shalom, shalom, you’ll find shalom the nicest greeting you know.” It was the opening song of Herman’s first Broadway musical, Milk and Honey, an upbeat comedy about a pair of middle-aged American tourists who meet in Israel and fall in love with each other and with the 13-year-old Jewish state.

The show had recently opened at the Marvin Beck Theater (now the Al Hirschfield), and within a few short weeks that lilting triple-time tune extolling the multipurpose Hebrew word had waltzed its way not only onto supermarket soundtracks, but also onto the roster of pop standards. (Eddie Fisher recorded a hit version.) It would even reach the American heartland—or at least the students at my Hebrew school in a Chicago suburb. At a special Friday night service where our class sang a few songs to round out the Union Prayer Book’s dry offerings, we warbled gamely about the word that “means a million lovely things / like ‘peace be yours’, ‘welcome home.’” Also on the program were two rousing anthems: Milk and Honey’s peppy title song—“This is the place where the hopes of the homeless and the dreams of the lost combine / This is the land that heaven blessed / And this lovely land is mine”—and “Anu Anu HaPalmach” (“We are the Palmach”), the assertive march of the pre-state Israeli army. That a couple of show tunes could make their way into a suburban shabbos in the early 60s, alongside a musical military boast, reflects not so much the profound Jewish connection to the genre of the Broadway musical (that’s a different story), but the cheery mainstream Zionism that was beginning to take root in America. Milk and Honey is a sweet show in the old romantic mold of The King and I or My Fair Lady, but it’s most worth remembering today for the innocent way in which it captured the naïve and celebratory foundation of many American Jews’ love affair with their putative homeland.

Even before the Six-Day War widened and deepened much of Jewish America’s sense of connection to—if not necessarily their knowledge of—the young state, an idealistic and heroic image of Zionism had already lodged itself in American consciousness through Leon Uris’s novel Exodus. The hardcover edition, published in 1958, held a spot on the best-seller list for more than a year; for 19 weeks it was number one. By 1965, the paperback had sold five million copies—its sales no doubt helped by the blockbuster film adaptation, released in December 1960 to become one of the five top-grossing movies of 1961. Starring Paul Newman as the brave and sexy sabra Ari ben Canaan, it borrowed the sweeping visuals and providential sensibility of popular Biblical epics like Cecil B. DeMille’s Ten Commandments (1956), and Ben Hur (1959): This was a narrative of just inevitability, of triumph amid toil and tragedy, of courageous Jews and inexplicably hate-filled Arabs, all presented in the cinematic splendor of Technicolor. In no time, according to the author Edward Tivnan—writing in his 1987 book The Lobby: Jewish Political Power and American Foreign Policy (a critical analysis as hard-hitting as last year’s infamous Walt-Mearsheimer report)—Exodus had become “the primary source of knowledge about Jews and Israel that most Americans had.”

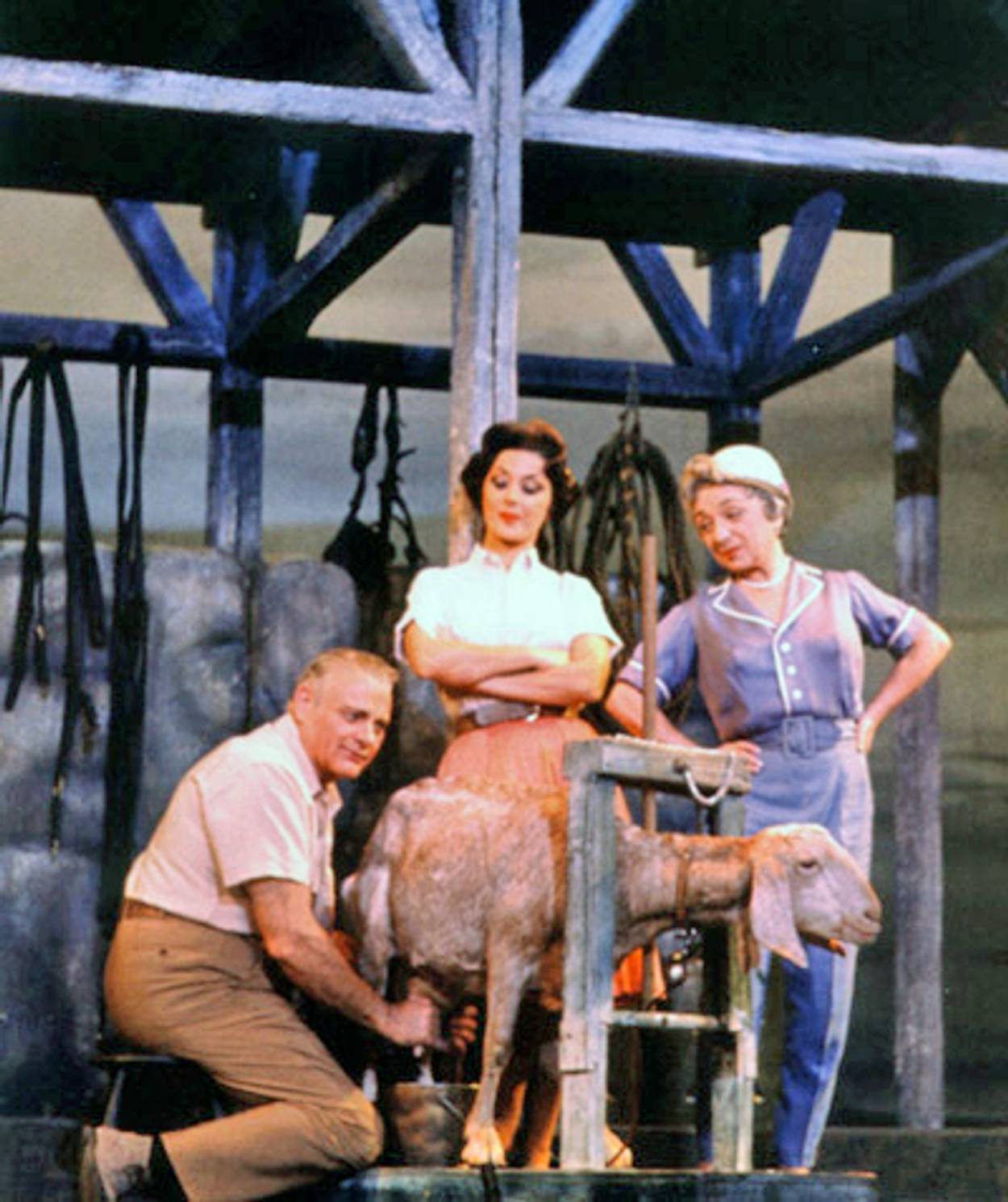

Milk and Honey, set a dozen years after Exodus, expressed a similarly jubilant and righteously proud attitude toward Israel—while remaining true to its own genre of the romantic book musical. In place of the film’s vast panoramas, suspenseful standoffs, and action-filled battles, Milk and Honey featured elaborate dance numbers, songs you could hum, multiple love stories, broad comic turns, and the colorful spectacle of a Jewish-Yemenite wedding. The plot centers on two middle-aged Americans, Phil Arkin and Ruth Stein (played by Metropolitan opera veterans Robert Weede and Mimi Benzell) who fall in love during trips to Israel—estranged from his wife, Phil is visiting his daughter, who has married a sabra and moved to a moshav; Ruth has come as part of a tour group of widows on a quest for new husbands. (The tour leader was played by Molly Picon, the great star of the Yiddish screen and stage; in her show-stopping song, she asks her dead husband Hymie for permission to remarry). In fact, “Shalom” is a little Hebrew lesson Phil provides when he and Ruth meet.

Most reviewers, however, found the setting far more compelling than the bittersweet love story. As Richard Watts put it in the New York Post, “it never seems nearly so important whether [Phil and Ruth] get together or not as it is that the deserts of Israel should flourish so gloriously.” One critic after another adopted the vision and vocabulary of the Zionist dream—images of the “people without a land” making the deserts of the “land without a people” bloom. Praising Milk and Honey’s “heartwarming integrity,” the New York Times reviewer wrote that “The [show’s] brighter flame is fed by the spirit of affirmation represented by Israel and its dedicated people, who are working to make real the ancient dream of a land flowing with milk and honey.” The Morning Telegraph applauded the way show honored “the zeal and hard work of the people who have transformed a drear and forbidding desert land into an Eden of green and prosperity.” Women’s Wear Daily promised that “for a few hours” viewers would “get the vicarious thrill of living in the colorful and phenomenal new land of Israel.”

In his 1996 memoir, Showtune, Herman writes that Milk and Honey was conceived as a “very happy and very positive” depiction of the country, meant to fan American affection. The initiative came from the real estate mogul Gerard Oestreicher, in his first foray as a Broadway producer. Oestreicher, who went on to produce such shows as Gigi, Sweeney Todd, and Starlight Express, had enjoyed Herman’s 1960 off-Broadway revue, Parade, but wondered whether Herman could “handle something ethnic.” Herman touted his credentials as a nice Jewish boy from New Jersey whose mother taught Hebrew songs as part of the music classes she gave at their local YMHA, and Oestreicher soon paid for Herman and the show’s librettist, Don Appell, to fly to Israel on the eve of its 13th Independence Day celebration.

The festivities produced an early scene in the show featuring an ecstatic, intricate hora. But, hosted by an official state representative, Appell and Herman quickly realized that they were being taken on what Herman calls a “propaganda tour,” meant to show off only Israel’s most glorious achievements; they broke out on their own to visit border towns in hopes of getting a more complicated picture—though they apparently never spoke with any Arabs. The chorus of “Milk and Honey” avowing “this lovely land is mine” (echoing the lyrics Pat Boone sang on the Exodus soundtrack asserting “This land is mine, God gave this land to me”) had no verses noting that there were, by the way, some other folks who also felt the land was theirs.

Herman encountered another obstacle on the tour: Soon after landing in Israel, he realized that “there was no such thing as a ‘musical heritage’ for a country that was only thirteen years old.” He told a New York Times reporter in 1962 that he established an “Israeli” sound by basing his score on “the kind of music Americans think of as Israeli—Ukrainian and Polish czardas rhythms, like the song Harry Belafonte made popular, ‘Hava Nagila,’ plus some Arabic wailing.”

In fact, only a couple of Milk and Honey’s tunes sound a little bit “ethnic”—and they’re the dance numbers: the “Independence Day Hora,” a spirited oompah number with lots of brass and hints of klezmer, and “The Wedding,” an overlay of cantorial chanting with Ruth and Phil’s pop love ballad “Let’s Not Waste a Moment” that busts out into yet another hora. For the most part, the show favors the pop conventions of Broadway’s heyday—pleasant, melodious tunes and perky lyrics, evident in the show’s love ballads and marches and in every musical Herman would go on to write.

Still the show bore marks of the surprises Herman and Appel encountered: ham sandwiches served at a Tel Aviv café, goats in the marketplace (in one scene, a real goat was milked on stage), and the eagerness of one sabra, Adi, to leave the toil of his moshav (and his very pregnant girlfriend) for the consumer comforts of America. Played by the Israeli actor Juri Arkin, Adi offers a counterpoint verse in the title song. “The honey’s kind of bitter and the milk’s a little sour / Did you know the pebble was the state’s official flower?” he sings. “How about the border when the Syrians attack? / How about the Arab with the rifle in your back?”

For Herman, these lines functioned to give this “valentine” of a show a “gray shadow that made it truthful” by articulating “the honest ambivalence that many Israelis have about their country.” Yet assigned to a comic character—a “grumbler”—the lines don’t take much air out of the otherwise exuberant show. In the end, Adi joins in the exultant chorus—and heads for the chuppah, the excuse for the Yemenite wedding scene. Closing the first act with a bang, this was a triple wedding noted by reviewers for its elaborate costumes and ritual “authenticity.” Part ethnographic exoticism, part good old Broadway spectacle, the scene begins with candles flickering behind a scrim, then moves from a solemn procession of three brides, three grooms, and their colorful attendants to a post-ritual dance of love in which, as the stage directions put it, “the brides bend to earth in complete submission to their husbands.” The couples are lifted onto chairs and with bright silks flapping, are twirled and bounced around as the curtain comes down.

By all accounts it was Donald Saddler’s energetic choreography—folk dancing, acrobatic workers hoeing and laying pipes, a dramatic solo in which Phil’s son-in-law expresses his love for the land—that most powerfully brought the show’s ideology to life. Reviewers described the dancing as “raw and lusty” and as possessing “vigor” and “majestic virility.”

Whether Herman knew it or not, Milk and Honey expressed the ideal of rejuvenation as envisioned by the early Zionist theorist and activist Max Nordau. The show celebrates not only the renewal of the “barren” land, but also the muscular awakening of the Jewish people by virtue of working that land. For Phil, Israel provides a kind of sexual recharge, the very manliness that Nordau promised Zionism would restore to the weak Diaspora Jew. After what is presumably a night spent with Ruth, Phil sings of how he wakes up feeling like “a young man”: “I will plow the desert in the morning / with the power of a boy / Guard the border if I have to / in the blaze of the sun / I can handle a gun like a toy.”

Audiences, too, responded favorably to this portrayal of Israel as the Jewish people’s political Viagra. A 1962 New York Times story quotes a fan letter Appell received from a Rhode Island woman who commented that it was “such a joy to watch a show about Israel and not see depressed refugees.”

Milk and Honey ended up garnering five Tony nominations (including Best Musical, Best Score, and, for Molly Picon, Best Actress.) But while the show had a respectable run of about 16 months, as well as a successful standard tour (my mother fondly remembers seeing it in Chicago in the early 60s), it has seldom been revived—and when it has been, it hasn’t fared well. Reviewing a 1992 production at the Forum Theater in Metuchen, New Jersey, New York Times critic Alvin Klein called the musical “understandably neglected”; a 1994 revival in New York at the now-defunct American Jewish Theater flopped.

In Showtune, Herman laments that the innocent, romantic book musical has gone out of fashion, supplanted by Sondheim’s brooding seriousness and by mass-market pop music as surely as Justin Timberlake and Beyonce have replaced the American songbook on grocery store sound systems. But the gee-whiz style, coy morality (Ruth and Phil dare not shack up until he tracks down his estranged wife and secures a divorce), and simple plotting aren’t all that make Milk and Honey feel dated. Today, even the most ardent Zionist can’t completely buy its fairy-tale version of the increasingly troubled state. Reality—whether that the vast majority of Israelis never farmed any land, but lived in cities; that the current generation of Israelis does not identify with the jolly idealism of mythologized pioneers; or that a Palestinian counternarrative demands a hearing—has intruded, irreversibly complicating Americans’ understanding of Israel’s past and present.

When Israel has made it to Broadway in recent years, it has mostly come in the form of straight drama with a strong whiff of self-importance: the unfortunate Judd Hirsch vehicle Sixteen Wounded and William Gibson’s hagiographic Golda’s Balcony, for example. And while Hollywood has seen at least one more musical about Israel—last spring’s Oscar-winning short West Bank Story, about a pair of star-crossed lovers, one Palestinian, one Israeli—its filmmaker had to turn to parody to indulge in optimism about that beleaguered land. Clever choreographic and musical quotes from the seminal 1957 Leonard Bernstein-Stephen Sondheim show, along with campy costumes and self-consciously over-the-top performances place West Bank Story firmly within an ironic register, further suggesting that old-style Broadway sincerity can’t accommodate such difficult questions as occupation, terrorism, and factional infighting.

A few years after Milk and Honey closed, Jerry Herman won his first Tony for Hello, Dolly!, the first of what Broadway historian Ethan Mordden would call his “Big Lady Shows” But one can hardly imagine a Golda Meir making the sort of ecstatic, sparkling entrance that announces—and worships—titles divas such as Dolly Levi, Auntie Mame, and even La Cage’s drag star ZaZa.

By the time Meir left office in 1974, the Six-Day War, the murder of 11 Israeli Olympians, the Yom Kippur war, and an occupation that seemed to be taking permanent root had made it nearly impossible to imagine a simple, celebratory vision of the no longer newborn state. But once upon a time, Milk and Honey could represent the shining moment (to borrow a phrase from Camelot, the like-minded musical that played down the street in 1961) when Israel—like Broadway itself—provided a stage for Jewish America’s fondest fantasies.

Alisa Solomon, the director of the Arts & Cuture MA program at the Columbia Journalism School, is the author of Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of Fiddler on the Roof.

Alisa Solomon, the director of the Arts & Cuture MA program at the Columbia Journalism School, is the author of Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of Fiddler on the Roof.