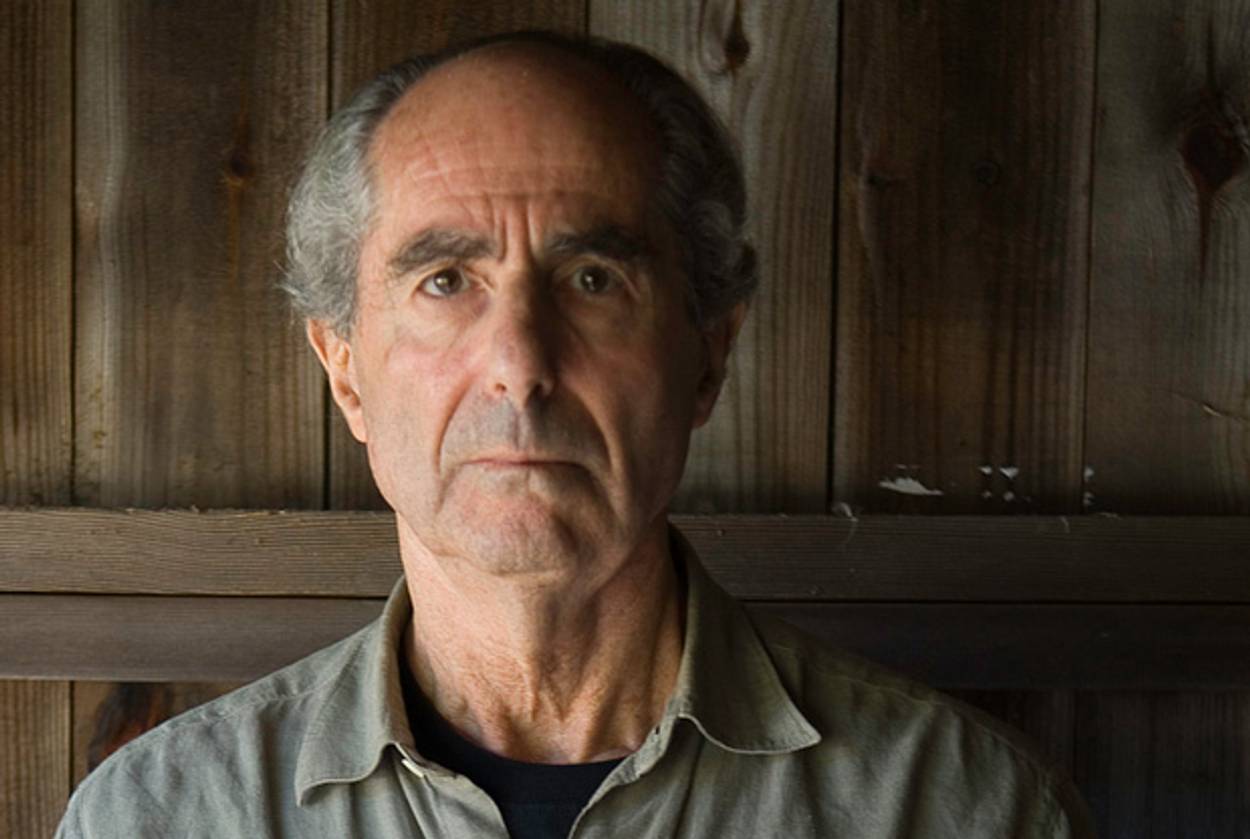

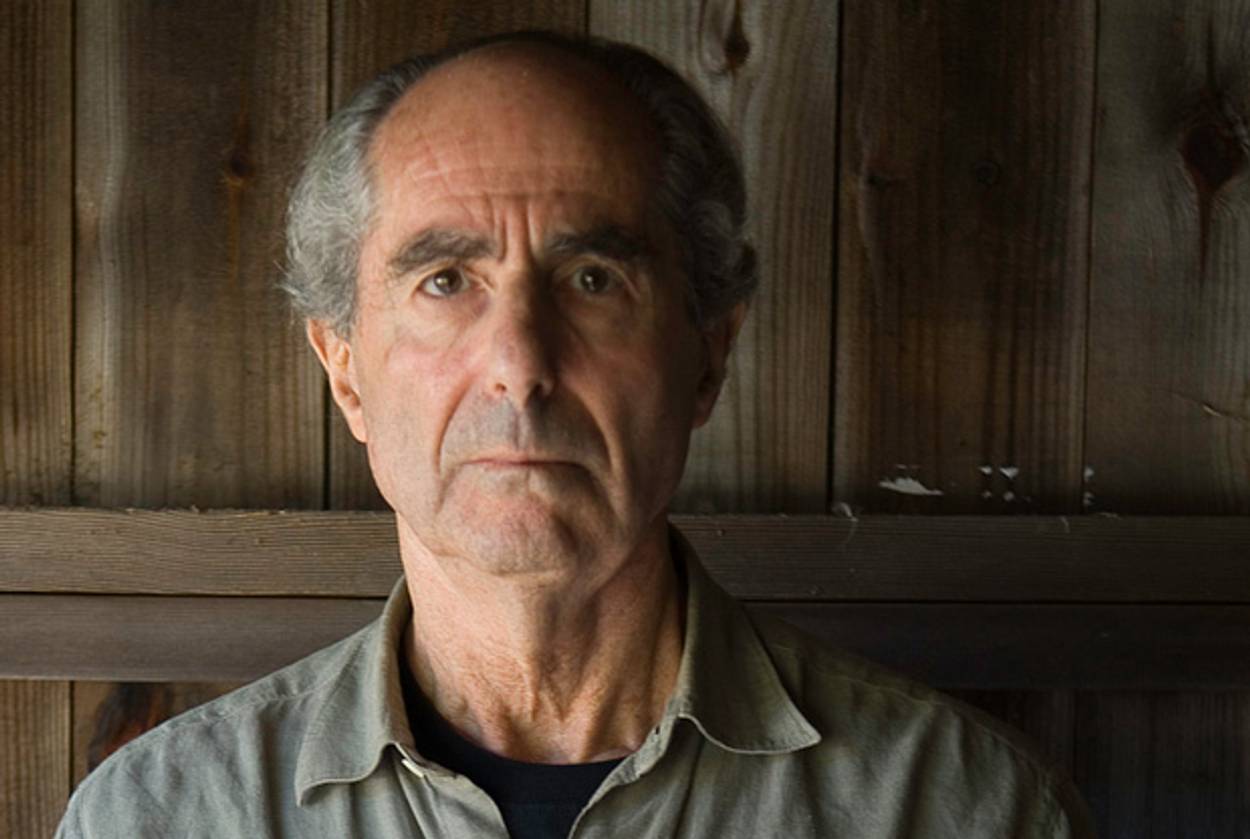

Is Roth Really Done?

After crafting dozens of fictional versions of exits and endings, the writer carefully manages his own

Hearing that Philip Roth is done with fiction was almost like finding his obituary on the front page. As a grad student whose research deals with Roth, I spend a considerable amount of my time thinking about, writing about, and reading the novelist’s works, and it was nice knowing that there were still more novels coming—something nobody has ever read before, to be discovered and understood.

Saddened and startled by the novelist’s announcement that there would be no more novels, I went back to his novels once more. What I found was that Roth has been attracted for a long time to the idea of ending his career on his own volition and not letting death (or illness) do it for him.

The most obvious place to look for hints of last week’s announcement was the last book in the Zuckerman saga, Exit Ghost, published in 2007, in which Zuckerman, Roth’s less successful alter ego about whom he has written nine novels, travels to New York after many years in Berkshires seclusion. Zuckerman shows the ravages of age. He is impotent and incontinent, but what is most detrimental for his writing is that he is losing his powers of recollection at an alarming rate. This loss—the “imp of amnesia”—not only makes him miss meetings. It does not allow him to remember what he has written and what he wishes to write next. In short, good fiction is no longer possible. Though I can’t know if Roth believes that he suffers from memory loss, as Zuckerman does, Exit Ghost makes it clear that Roth has no intention of having his books show signs of mental deterioration, or what Zuckerman calls “a slide into senselessness.”

But it seems that many years before facing old age, Roth was already fascinated by the idea of looking at his career and knowing that it is over. The first of the Zuckerman books, The Ghost Writer, published in 1979, features Zuckerman as a young aspiring writer. Having published a number of short stories, he visits a potential mentor E. I. Lonoff who is at the height of his career. In retrospect, the older Zuckerman narrating the novel can tell us that not many years later Lonoff would die and not publish anything new for a while before his death. Thus, Zuckerman can assess Lonoff’s entire oeuvre, letting us know that Lonoff’s work was nearly done when they met. The young Zuckerman is witnessing a writer nearing the end of his career and asking whether it was worth the effort.

Reexamining a life’s work seems to be exactly what Roth decided to do. Lonoff seems to think that his efforts were futile, but Roth does not share his fictional character’s disappointment. According to a report in Salon, Roth told a French interviewer that when he reached 74 he decided to reread his life’s work in reverse chronological order. Roth said: “I wanted to see if I had wasted my time writing. … And I thought it was rather successful.” In the interview Roth chose to quote the boxer Joe Louis’ “I did the best I could with what I had,” but he could have quoted from the Henry James story that Zuckerman reads twice during his night at Lonoff’s.

In James’s “The Middle Years,” the ailing novelist Dencombe receives a copy of his latest book, which he knows will be his last. He sits down to read it and is pleased with his final effort. The author does not remember the process of writing and is surprised by his own novel: “What he had chiefly forgotten was that it was extraordinarily good.” On his deathbed Dencombe gives a more mysterious account of his his life in words that strangely anticipate Joe Louis’. This passage from James is quoted at least twice in The Ghost Writer: “We work in the dark—we do what we can—we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.” These scenes of an author looking back at his life’s work and knowing that it is over have been a part of Roth’s imagination for at least three decades.

Roth’s fiction shows that he has been thinking about this moment for a while now, so it makes sense then that once he has taken this final decision, he will stick to it. In fact, we are told that he has in fact not written (or read) a word of fiction for the last three years. Yet, there has been already one sighting of Roth the storyteller since then. Last September the New Yorker website published an open letter to Wikipedia. A great example of the famous Rothian diatribe, it was a fascinating and detailed account of his encounters with two men, only one of whom was the inspiration for The Human Stain, and his frustration with Wikipedia for claiming the wrong man as muse. This letter may be just another piece of support for the tired wisdom that there are few things more dangerous (or tedious) than a retiree with a typewriter. It might also be a sign that Roth cannot totally refrain from writing and publishing stories, whatever form his inventions may take.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

David Hadar, a graduate student at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, is a contributor to Haaretz.

David Hadar, a graduate student at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, is a contributor to Haaretz.