Jewish Rap Kingpins and the Politics of Musical Identity

Campus Week: Your guide to today’s leading Jewish rappers, and where they started from, and now they’re here

This article was originally published on September 12, 2016.

Any Jewish rapper working today owes an enormous debt to Def Jam Records founder Rick Rubin and the troublemakers he released upon the world—Michael “Mike D” Diamond, Adam “Ad Rock” Horovitz, and Adam “MCA” Yauch. From the day Licensed to Ill (1986) dropped, the Beastie Boys—that rollicking, nasally, raunchy trio of New York Jews—has been unapologetically themselves, in all their irreverent glory.

Rubin and the Beastie Boys created a space for themselves in popular music that hadn’t existed in a meaningful way since before World War II: a space for Jews to coexist with black music, while also distinguishing themselves from “whites.” The Beasties meant to offend, meant to subvert assumptions—and their way of achieving that (besides giant inflatable penises on stage) was to not only behave in a manner oh-so-unbecoming of well-to-do New York Jews, but to create some of the most enduring rap albums of the era while paying proper homage to the African-American artists who created the genre in which they worked. Their 1988 album Paul’s Boutique remains one of the greatest rap albums ever made, and essentially set the stage for the sample-heavy magpie sensibility that has ruled the genre off and on ever since.

The Beasties expressed their own sense of their musical place on “Shadrach,” one of the tracks on the seminal Paul’s Boutique. The title comes from a story in the Book of Daniel, which goes as such: King Nebuchadnezzar, perhaps a little bored, commissioned a golden image to be constructed in a local plain. All Babylonian officials were required to bow down before the image, and all who failed to comply would come to a fiery end. Word got to Nebuchadnezzar that a trio of rogue Jews (Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego) had refused to take a knee, and Nebuchadnezzar called the three before him. Aware of the punishment that loomed, the boys told Nebuchadnezzar that God would be with them. They were thrown into a fiery furnace, but rather than burn to a crisp, they stood in the fire, a fourth figure apparently visible alongside them. Nebuchadnezzar ordered them out of the fire, whence they emerged unharmed. The king declared that any who spoke against the God of these Jews would suffer a fate worse than death.

The self-mythologizing of “Shadrach” by a trio of rabble-rousing Jews is unmistakable. The three rappers were thrown into the fire of moral judgment (presumably, Rick Rubin was the mysterious fourth man), refusing to conform to the dominant social mores of white Christian America. But instead of accepting a promotion from their captors, they flip ’em off and chant their strange names at the top of their lungs for the chorus, “Shadrach, Meshach, Abednego!” (The use of this biblical story throughout the history of black American music is well-documented: Louis Armstrong and Sly and the Family Stone, among others, wrote “Shadrach” songs.)

Though the Beasties were rarely so explicit about the politics of musical identity in their lyrics, they were blatantly Jewish, from their nasally delivery to their penchant for performing in Orthodox Jewish garb. Judaism wasn’t always a part of their actual lyrics, but it was the defining characteristic of who they were: They were New York Jewish kids, and they flaunted it, even after they moved to L.A.

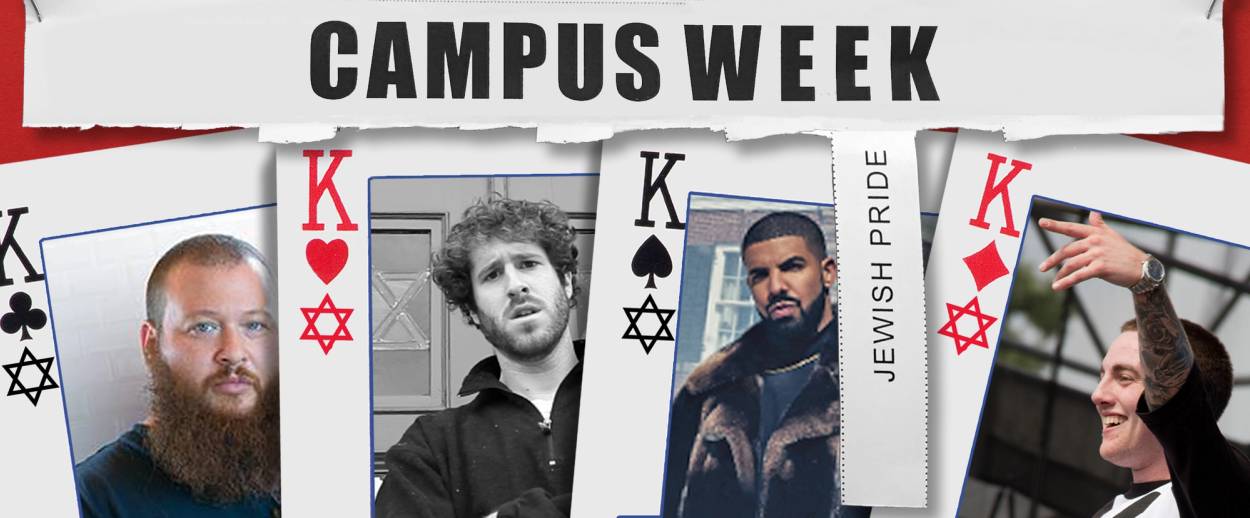

So, how do today’s Jewish rappers stack up against the Beastie Boys? For your listening pleasure, here are the four most prominent Jews in rap* today, with an exploration of which flavor of Jewish they are and how they walk the walk and talk the talk. Headphones recommended.

*Apologies to Hoodie Allen, Socalled (strongly recommend watching this music video), Asher Roth, and Shyne.

Action Bronson

Bronsolino was raised Muslim, but since his first mixtape, Bon Appetit … Bitch (2011), the Flushing rapper has always peppered his rhymes with Jewish references (though according to Bronson: “Anything that has to do with pig, I’m eating”). Born to a Jewish “free-spirit hippie” mother (his words) and an Albanian immigrant, Arian Aslani, aka Action Bronson, is a mountain of a man who sports a frizzy red beard that makes his head seem even larger than it is, and at around 300 pounds, he’s got the type of heft that gives him an almost regal bearing; to watch him sample haute cuisine in his Vice eating series, Fuck, That’s Delicious, is what I imagine watching William Taft eat must’ve looked like.

The “haute” part matters deeply to Bronson. Directionless and otherwise engaged in petty crime in his 20s, he decided to attend culinary school, where—well, here he is in a 2013 interview:

“That school was where everything popped off,” he says. “I met the mother of my children there. Fucked her in the locker room. And then we went back, and I think we made filet mignon that day.”

He spent a few years in New York as a chef, and today, Fuck, That’s Delicious episodes see Bronson traveling all over the world with his entourage (usually another rapper named Big Body Bes) and ordering one of everything in restaurants where you typically don’t see 300-pound tatted-up Albanian-Jewish hybrids rolling through, reeking of weed.

As a rapper, the love of fine food is the basis of his persona. It’s reminiscent of MF DOOM’s Mm…Food (2004) in that consumption and the way in which we choose what we put into our bodies defines us, the difference being that DOOM was talking about a spiritual hunger, whereas Bronson seems, like, legitimately famished. But still, he insists on the best. Here he is on “Twin Peugeots,” from Blue Chips 2 (2013):

My dad was right when he said I was a strange, fuck

Now every meal is calamari and boudin blanc … Eggs Rothko

The handmade suit cloth I got the sports coat

And lest you think Bronson’s songs are nothing but a laundry list of expensive foods and quick reviews of five-star New York restaurants, rest assured that he also douses every song in references to obscure New York athletes from the 1980s and ’90s (Randy Velarde, Marty Janetty, and Clarence Weatherspoon, to name a few). Gifted with a distinctly New York flow (he’s been accused of imitating Ghostface Killah in the past, a charge that has some merit), Bronson can comfortably snap from a pleasant sing-song cadence to a rapid-fire delivery. It helps, of course, to work with producers who use outside-the-box samples for an outside-the-box rapper; at various points, frequent collaborator and Brooklyn producer Party Supplies has thrown in samples from Peter Gabriel, Tracy Chapman, and Turkish rock band Mazhar-Fuat-Özkan.

Bronson makes party music you can listen to anytime, a guy who’s having (admittedly misogynistic, materialistic) fun and just wants to tell you about it. Blue Chips (2012) and its successor are prime examples of a kind of joyous raucousness that’s tough to fake, and his latest album, Mr. Wonderful (2015), for all its faults, is in that same vein. He’s a throwback in that way, as a lot of New York rappers are: Throw on a beat, and the bars will come. It’s refreshingly unpretentious, even if the cover of Saaab Stories(2013) rightfully makes you queasy.

Jewishly speaking, that part of his identity is more punchline fodder than anything. Songs like “Steve Wynn,” “Falconry,” and “Morey Boogie Boards” are chock-full of lines like this:

So wake up early, hop off the shitter

Employ a lawyer that’s been bar mitzvahed

Never trust goyim, see me sippin’ spritzer

Hookers with Spitzer

Bronson is a man of multitudes; like Milo Yiannopoulus, he seems to be Jewish when it’s convenient for him, just as he’s Albanian when it’s convenient, Muslim when it’s convenient, and so on. Issues of identity aren’t terribly central to his act. He’s an original American hybrid.

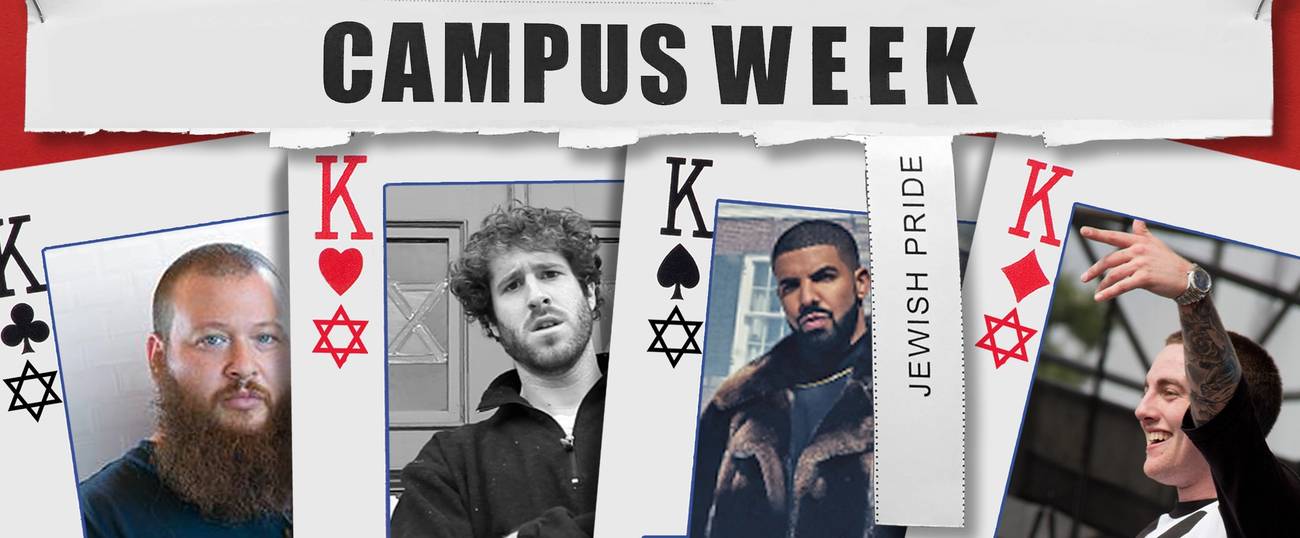

Mac Miller

“My name Mac Miller/Who the fuck are you?”

The Pittsburgh-born rapper and self-described “bad little Jew” doesn’t mince words and, like Bronson, he’s spent a good chunk of his career pigeonholed as a college-radio rapper. Unlike Bronson, Miller seems to have designs on something beyond that disdainful label, and if his last album, GO:OD AM (2015), is any indication, he’s well on his way.

Miller was born Malcolm McCormick, the son of a Jewish mother and a Christian father. He was raised Jewish, had a bar mitzvah and, according to Miller, his favorite holiday food is his grandmother’s noodle kugel, which he lovingly describes as “fuckin’ awesome.” Scrawny, tatted up, and often clad in some sort of Pittsburgh sports attire, Miller’s been releasing music since he was in high school. At 24, his rise from indie king to major-label signee has been nothing short of meteoric.

Miller’s early high school mixtapes featured the rapper using the embarrassingly cheesy moniker Easy Mac, so for his sake and ours, we can skip over his (literally) sophomoric attempts. During his senior year of high school, Miller signed with the Pittsburgh-based indie label Rostrum Records, joining Wiz Khalifa, who’d rise to prominence right along with Miller. With mixtapes like K.I.D.S. (2010) and Best Day Ever (2011), Miller began to make a name for himself as a hyperactive braggart with an affinity for weed and the Steelers (he’s certainly the only rapper to describe his income as “Willie Parker money,” as he does on “Good Evening”). And, of course, “Donald Trump,” the first single off of Best Day Ever, went platinum at a time when Trump was shorthand for nothing but obscene wealth, introducing Miller to mainstream audiences.

The song’s also the most succinct summation of his early career ambitions. In the video for “Donald Trump,” Miller, he of the runty frame and retroactively horrible chinstrap beard, raps: “That’s the way it goes when you party just like I do/ Bitches on my dick that used to brush me off in high school/ Take over the world when I’m on my Donald Trump shit.” Rappers have been using a chip on the shoulder as a motif for as long as the genre’s existed (and beyond the point that any of their doubters can possibly remain) but for Miller and other white rappers, it’s the bedrock of their personas—white rappers are, fairly or not, regarded skeptically outside the mainstream (see: Macklemore and Kendrick Lamar, 2014 Grammy Awards). Miller, perhaps sensing this, built up cred as a producer under the name “Larry Fisherman” as he improved as a rapper, working with everyone from Vince Staples to Schoolboy Q (Rick Ross, on Miller’s “Insomniak”: “Mac Miller/ My real n—a”); consequently, he’s appeased the tastemakers that have so much to do with what succeeds and what doesn’t in the rap world. But it’s not just likability that’s elevated him to these heights.

If those Rostrum mixtapes were high school escapism, then his first studio albums (also with Rostrum), Blue Slide Park (2011) and Watching Movies With the Sound Off (2013) were his intro-level college courses. The production value skyrocketed as Miller moved beyond simple hedonism, musing on everything from his drug addiction to the trappings of mainstream fame. Here he is on “I’m Not Real,” with Earl Sweatshirt:

Allowing birds to fall to their death before they even fly

He and I are not the same

Doctor, doctor, please prescribe me something for the pain

Money in machines, those will make you change

Blue Slide Park was also the first independent album to debut at No. 1 since 1995 (the last album being Snoop Dogg’s Dogg Pound). And yet, Miller didn’t really garner widespread critical acclaim until last year’s GO:OD AM, his first album for a major label, where he finally synthesized the sense of fun of early work with his personal demons to create thoughtful, world-weary songs that were eminently catchy. “Weekend” still gets huge radio play:

What hasn’t changed is Miller’s use of his Judaism, which is similar to Bronson’s. It’s used to invoke his nerdy side, a method of self-deprecation (“I always do it big like a Jewish nose”) that’s immediately followed by a reminder of how successful he is. Jewish is shorthand for nebbishy, essentially.

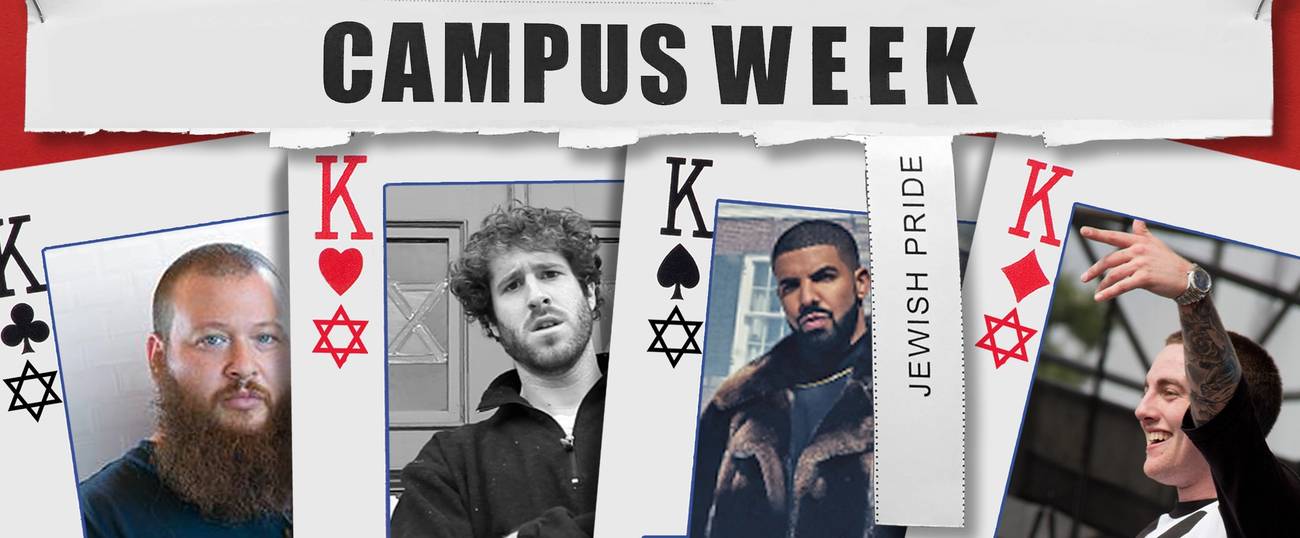

Lil’ Dicky

No mainstream rapper has ever been as openly, deliberately Jewish as Dave Burd, aka Lil’ Dicky. His first mixtape, So Hard (2013), features Burd standing in the middle of a gigantic, flaming Magen David, and the first track, “Ham,” starts with “Whoa, so hard/ Jews is never supposed to go ham, but fuck it.” It’s a joke, but on another level, it’s illustrative of the struggle at the center of Dicky’s persona—the tug-of-war between Dave Burd, the nebbishy Jew who openly wishes he “could just say black things,” and Lil’ Dicky, the brash, confrontational rapper who goes clubbing with Snoop Dogg and Fetty Wap.

Dicky’s said he felt he “misrepresented” the preeminence of Judaism in his identity in So Hard, and yet, his first studio album, Professional Rapper (2015), released after he made that statement, continues to invoke his Jewishness as central to the persona he’s constructed. On “Parental Advisory (Interlude),” his mother reminds him to get to bed early the night before a show, and when Dave chafes at being lectured (Did Puff Daddy have to deal with this, he wonders?), she tells him, “I’m trying not to be a Jewish mother here, but I really think you’re underestimating this.” He continues to weave “kike” into his rhymes with abandon, a way of identifying himself as Jewish while also distinguishing himself from the type of Jew who’s so stuffy as to take offense at a Jew using that word.

Even though Dicky sees himself as fundamentally apolitical (“I don’t even know the first thing about what Obama do/ I’m better off telling y’all what LeBron been doing”), the particulars of the way he deploys Judaism—as central to Dave, but punch-line material for Dicky—speak to a very specific modern Jewish philosophy. Dicky tries to hold Judaism and what it represents in his music—as something unbecoming of a rapper with aspirations like he does—at arm’s length, while also being unable to escape the way it shaped who he is (see: “$ave Dat Money), and owning that.

The complexities of that identity struggle aside (to say nothing of his relationship with blackness), Dicky’s actually a bit of a throwback. Whereas the next wave of rap seems like it’s going to skew toward the trap-house sensibility, Dicky’s philosophy seems to be couched in a more classical form: good beat, well-constructed concepts to drive each song, and punchline after punchline. Like Bronson, it seems to come from a deep appreciation for his predecessors and the more lyrically focused corners of the genre. He’s new-school in a lot of ways (he came to prominence on YouTube, his lyrics directly address the metatextual aspects of his career more than most rappers care to, his Curb Your Enthusiasm-inflected brand of humor), but when it comes down to the technical aspects of his work, it’s usually as simple as hopping on a beat and letting the bars fly. Which is something he seems to be preternaturally gifted at doing.

Dicky is reflexively self-conscious, which is interesting to a point, but after a while it starts to come off as narcissism; on the outro to Professional Rapper, he describes this point in his career as “the moment when Truman hits the wall,” referring to Truman’s revelation of a life outside of himself in the movie The Truman Show. Except Dicky seems to interpret that moment as when Truman recognized his own importance, which speaks to the ego it takes to rap with the confidence that he does. Dicky pines to be “one of the greats”; at 28, with a No. 1 rap album under his belt, it doesn’t sound so ridiculous right now.

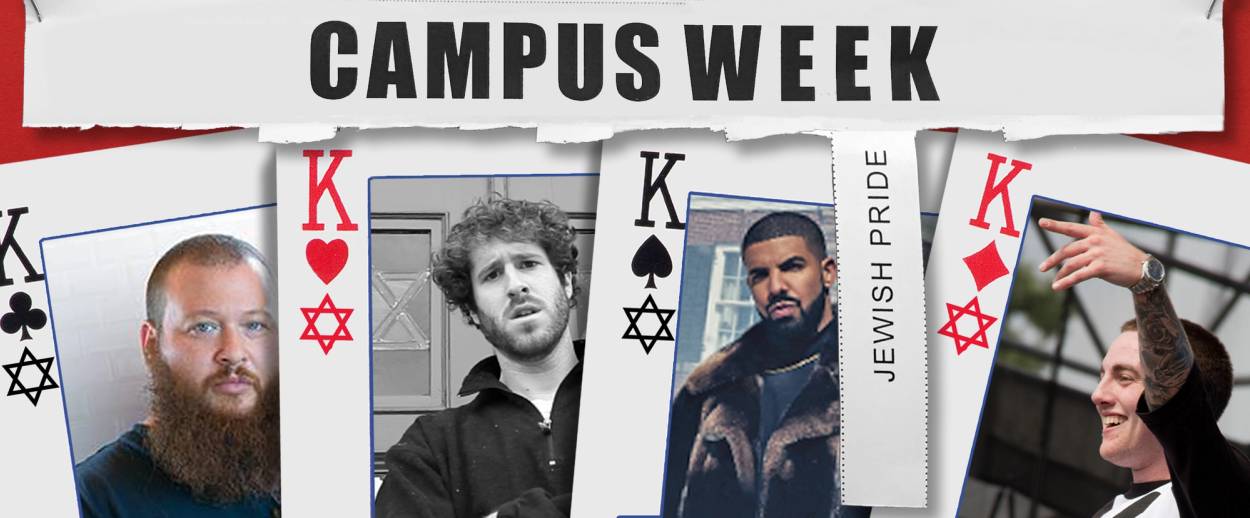

Drake

As it stands, there is no rapper on the planet more popular than Drake. He’s the most streamed artist in Spotify history, his last six major releases have all gone No. 1, and a Drake feature can put a lesser rapper on the map. Between the release of his masterful If You’re Reading This, It’s Too Late (2015), his public beef with Meek Mill, and the cultural event that was the video for “Hotline Bling”—about to reach a billion views on YouTube any minute; embedding it here seems practically redundant—it’s fair to say that Drake owned 2015. The release of Views (2016) kept the momentum going.

A gifted rapper and singer, Drake has cemented his place in the mainstream by attaching himself to producers with great pop sensibilities; meanwhile, he’s able to maintain his status as a critically acclaimed rapper by innovating not only in a lyrical or musical sense but in what it means to be a rapper in the public eye.

Make no mistake: Drake’s early mixtapes are unlistenable. Room for Improvement (2006) is about as easy of a setup as you can ask for, and Comeback Season (2007) only reaffirms the sentiment of the first attempt. Recorded at the tail end of his Degrassi days, they’re empty boasts, overproduced, and not really representative of his later music. The only thread he’s maintained since those days is the emotionality of the music.

With the release of So Far Gone (2009), Drake, who was starting to make a name for himself after signing to Lil’ Wayne’s Young Money Entertainment, not only fully shed his Degrassi label, but truly dropped one of the best mixtapes of the 2000s. As has become his trademark, he apologized to past loves for his callousness and lack of restraint, all the while plotting his next conquest. For So Far Gone, Drizzy worked with producer Noah “40” Shebib; 40, as he’s known, bonded with Drake over their appreciation for Kanye West’s 808s & Heartbreak (2008), a dark, textural album heavy on pathos and liberal (perhaps too much so) with autotune. Drake’s sound now—heavy, nocturnal beats that are as suited to his crooning as they are to sneering, vicious bars—is in its infancy on So Far Gone, but even then, it’s spectacular.

After that, everything he touched turned to gold. His debut studio album, Thank Me Later (2010), cemented his status as one of the preeminent rappers in the world, embracing the rapper/businessman model of Jay Z and Diddy with the way it elevated his personal record label, OVO. Yet he was still dogged by accusations of being “soft,” which he didn’t seem to mind; in one of his characteristically mysterious interviews, he referred to his detractors, saying, “You notice they don’t criticize the music itself, though. … I’m OK with that.”

Since then, Drake’s career has seen nothing but overwhelming commercial success, along with serious artistic achievement. Take Care (2011), the follow-up to So Far Gone, was a sprawling, thoughtful meditation on his new fame, less boastful than his past work. “Headlines” and “Make Me Proud” remain some of his most popular songs, while tracks like “The Real Her,” “Lord Knows,” and, especially, “Marvins Room” are perfect snapshots of the Drake aesthetic—dark, brooding, and petty. The central motif of “Marvins Room” is Drake calling up an old girlfriend, telling her she could “do better.”

Nothing Was The Same (2013) was yet another step up, and with the depressive Take Care in the rearview mirror, Drake talked shit on a level he couldn’t before. “Worst Behavior” and “Started From the Bottom” are two of the most fun songs he ever recorded, and “Pound Cake/Paris Morton Music 2,” with Jay Z, features a beat that lesser rappers would kill for. Drake’s so good on the song, he overshadows it.

Following the surprise releases of If You’re Reading This, It’s Too Late and What a Time to Be Alive (2015), his two most straightforward rap albums, the stage was set for Views, an album he’d been teasing for years. Meanwhile, he’d escaped a beef with Meek Mill over ghostwriting accusations that he should’ve lost, and started to make noise as an anti-internet rapper. “Fuck going online, that ain’t part of my day,” he said on “Energy,” and yet, his meme-ability, frequently updated Instagram account, and domination of online hip-hop gossip say otherwise.

Views had insurmountable hype. Of that, there’s no doubt. But still, the album didn’t live up to his past work, and even though it still debuted at No. 1, Drake’s insistence on delving deeply into his psyche had started to grate.

Drake has straddled his given identities like very few rappers do. His father was black, and he comfortably uses the n-word; however, his mother was white and Jewish, and even though being black and Jewish isn’t a contradiction in any way, it still is perceived that way in the mainstream. He’s embraced it, though. Though his Judaism is usually manifested in punchlines (“Bar mitzvah money like my last name Mordechaiiii”), he still posts Passover pictures on Instagram, and “You and the 6,” addressed to his mother, is as good as a year’s worth of phone calls. And of course, the music video for “H.Y.F.R.” is the greatest moment in Jewish hip-hop history. What other rapper could pull off a bar mitzvah-themed music video with Lil’ Wayne, DJ Khaled, and Birdman?

***

To read more from Tablet magazine’s special Campus Week series of stories, click here.

Jesse Bernstein is a former Intern at Tablet.