Mel Brooks Kicks Larry David’s Skinny Ass

Part II in a continuing series on the decline of Jewish vulgarity

The first crass biblical joke was directed squarely against God by Sarai, the mother of the Israelites and the world’s first Jewish stand-up comic, who famously laughs at God’s plan to give her and her husband, Avram, a son. Her point, more or less, is “You expect a 99-year-old man to get it up, and with old shriveled me?” Adonai and his angels—a tough crowd—don’t laugh, but we still do, several thousand years later.

And the jokes continue. Aside from Judaism, it’s hard to think of another religion that specializes in lambasting the master of the universe, a sarcastic form of rebellion that climaxes with the book of Job. Moses’ Israelites are sharply satirical. “Weren’t there enough graves in Egypt? You had to drag us out to this wilderness?” they carp.

The Bible’s crude gibes are equally directed at the dimwitted enemies of Israel. Balaam’s ass thwarts his master, stopping Balaam from prophesying against Israel. The Talmud’s rabbis insisted that when the ass complains “You’ve been riding me all day” this means that Balaam has been shtupping his beast of burden (Sanhedrin 105b). Traditional Purim-shpils endlessly barbecue the hapless Haman, that numbskull who thought he could decimate Jewry.

But there are no better targets for Jewish humor than Jews themselves, especially respectable ones. In one Purim-shpil, Mordechai, the virtuous uncle of Esther, recites a parody of the Yom Kippur confession, the Vidui. Here is the scholar Jeremy Dauber’s translation (capital letters represent the prayer’s Hebrew verses):

FOR

I go gladly with young girls into the stable

THE SIN

Much more gladly to bed

THAT WE HAVE COMMITTED

Even with a widow

BEFORE YOU

Quite quickly I do it

ABRAHAM SINNED

Has a large shop,

Makes all the young girls lame

ISAAC SINNED

His thing is quite sharp,

Makes all the girls witty

Dauber cites Mikhail Bakhtin’s idea that the raucous mockery of authority figures acts as a safety valve, a way of making sure that authority remains strong. Abraham avinu, like the Talmud’s rabbis, is no stuffed shirt, but a man with a penis, like Milton Berle at a Friars’ Club roast. (Yes, penis size is discussed in the Talmud, Dauber informs us.) The same student who recited Mordechai’s mock-Vidui was, in the study hall, earnestly immersed in the Gemara.

Bakhtin’s argument that humor is a means to prop up authority can be sensibly applied to medieval Purim-shpils. But Jewish laughter in the modern age pricks harder. Then it’s not a safety valve but a serious battle with authority. In 20th-century America, the ripest target for Jewish humor was the Jewish claim to respectability, which went hand in hand with assimilation.

In 20th-century America, the ripest target for Jewish humor was the Jewish claim to respectability, which went hand in hand with assimilation.

American Jewish humor at its best asserted the neurotic glory of Jewishness against the white-bread norms of middle-class life. A cookie-cutter existence in the suburbs meant the stifling of any unruly Jewish impulses, in order to swear fealty to goyishe norms of proper behavior and good citizenship. Being calm and neighborly, the gentile ideal, required not getting upset or anxious, two traits that have been closely allied to Jewishness from the start.

Those mostly Jewish gods of modernity, Hollywood’s moguls, with their bad manners and grandiose egotism, produced movies that were the stark opposite of their own florid personalities. During Hollywood’s golden age they ensured that cinema stayed clean and decent—and non-Jewish. The Hollywood musical, especially, presented a never-ending paean to wholesomeness. But by the ’70s Hollywood was spotlighting discontented riffraff like the heroes of Taxi Driver, Midnight Cowboy, and other gritty sagas. Jewishness appeared on the big screen too, in Woody Allen’s cuddly, affected Annie Hall, but there was little attention paid to the Jews’ messy, offensive edge. Until, that is, the advent of Mel Brooks, the biggest source of Jewish vulgarity in movies.

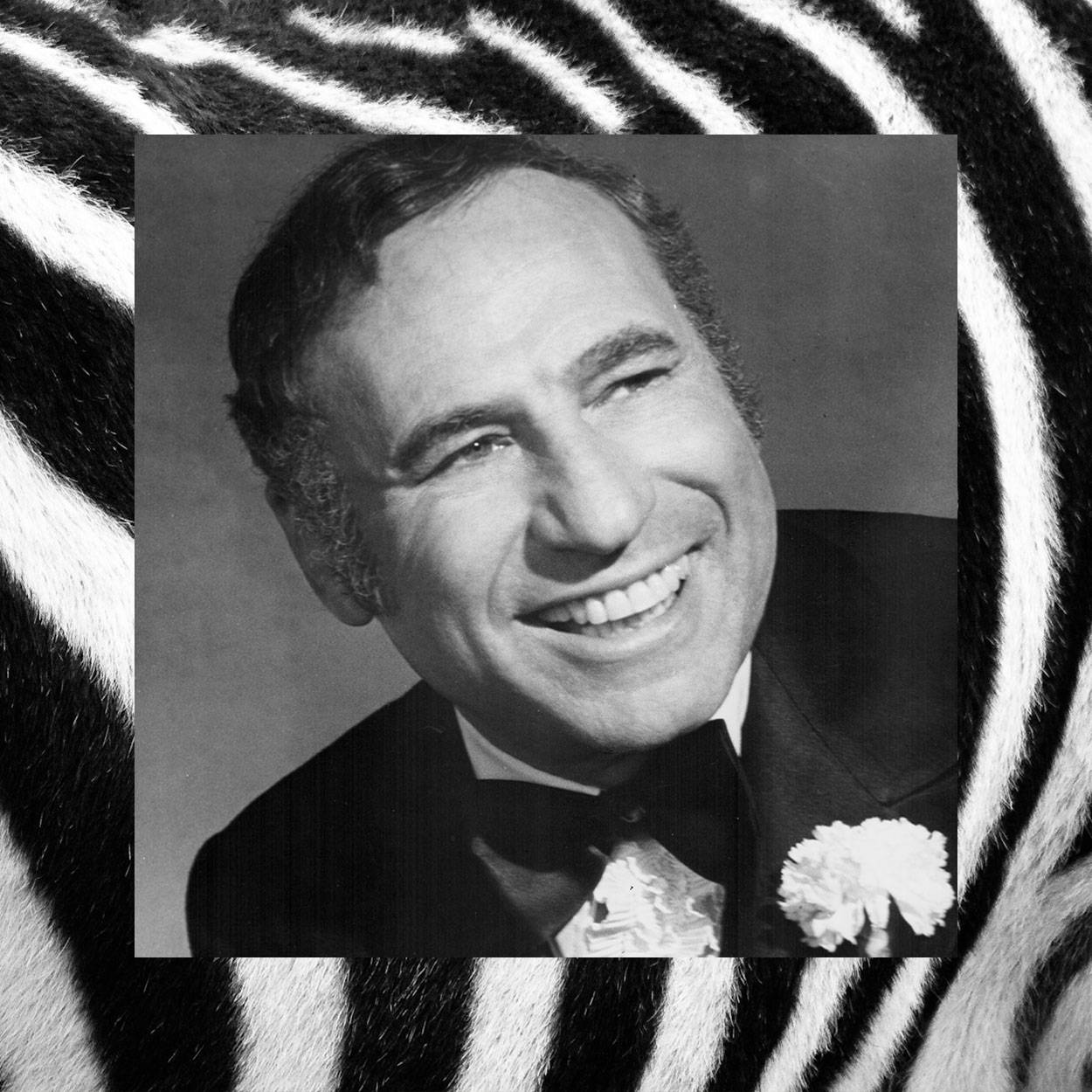

Brooks, who is still alive and kicking at age 96, has had a near-endless comedy career. He began as a tummler in the Catskills, wrote for Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows, and then hit it big with the comedy album he made with Carl Reiner, The 2,000 Year Old Man, which Queen Elizabeth reportedly found quite amusing. (In a sad instance of dynastic decline, Brooks’ partner Carl Reiner passed the comic baton to his son Rob Reiner, aka Meathead, a wan liberal voice of reason.) Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein, released in 1974, became sacred texts for my high school circle of friends, ranking up there with Monty Python. History of the World, Part I, which came out in 1983, is the third member of Brooks’ comic triumvirate. Miraculously, 40 years later, his History of the World, Part II, filmed last year, will be released March 6 on Hulu.

As a kid on the streets of Williamsburg, Brooks told Playboy in 1975, he perfected his “corner shtick”: “You had to score on the corner—no bullshit routines, no slick laminated crap. ... The story had to be real and it had to be funny. People getting hurt was wonderful.”

Brooks’ best in-your-face tour de force was History of the World, Part I, an immortal classic from its opening parody of 2001’s apemen, who salute the dawn of humanity with jerking-off gestures, to the coming attractions at the end. History of the World, Part II, we are informed, will feature Jews in Space, a Viking funeral (complete with horned Vikings, or are they Jews?), and Hitler on Ice, where the Fuehrer executes some dainty spins.

Like the Three Stooges’ Moe (born Moses Harry Horwitz), Brooks will be forever linked to his Hitler parodies. Brooks cut his comic teeth with The Producers, which he wanted to call Springtime for Hitler—a title unimaginable on a marquee, it was decided. Brooks’ producer cluelessly suggested that the film’s sublimely awful musical, put on by Zero Mostel and Gene Wilder, be retitled Springtime for Mussolini, but Brooks thankfully won that one.

History of the World satirizes the Roman empire with sloppy gusto, along with ancien régime France (“it’s good to be the king!”) As David Denby comments, the film is a “celebration of barbarous behavior throughout the ages.” But Brooks’ most stunning sequence is devoted to the Spanish Grand Inquisitor Torquemada, known for burning conversos. Brooks plays Torquemada as a cheerful smoothie, dapper in his red robes, who delights in the tortures he is about to inflict on the Jews. Burning Jews is an irresistible treat, a delighted Brooks confesses. An auto-da-fé is, he sings, what “you know you shouldn’t do ... but you do it anyway.” The Spanish Inquisition was sufficiently remote in time that Brooks could get away with making fun of its brutality, and of the Jews’ sufferings.

With the lavish Torquemada sequence, which cost more than the rest of History of the World combined, Brooks roasted the fantasy purveyed by classic Hollywood’s Jews, who sold the American dream to the masses. Brooks wanted to parody the glossy innocent cheer of a big number in a Hollywood musical, which poured on the spectacle to overwhelm the audience with irresistible feel-good vibes.

“Bring on the nuns!” yells Brooks’ Torquemada, and a line of swim-capped shiksas plunges gracefully into a swimming pool, synchronized as in an Esther Williams musical. In response the hirsute, caftan-wearing Jews plummet clumsily down a water slide. They thrash about, their tangled rabbinical beards floating underwater, while the immaculate goyishe beauties trace acrobatic patterns all around them. These Aryan angels’ effortless smoothness sets off the hairy, awkward Jews’ floundering. Earlier, they have had their balls “pingponged” (as Jackie Mason, one of the victims, puts it), made ready for the auto-da-fé.

Brooks’ Torquemada routine mocks the array of untouchable female gentile flesh put on display in Hollywood musicals by Jewish studio heads. These Jews didn’t allow even the slightest trace of Jewishness into their pictures; Jews didn’t belong in Hollywood’s white-picket-fence America or its sanitized idea of history. But in the real history of the world, Brooks was saying, Jews played an outsize role as buffoons and truth-tellers. Even when they were victims, about to be burned alive by the Inquisition, they preserved their comic chops the same way they held on to their tallis and tefillin. The swimming shiksas were there for decoration, but the Jewish jokes were what really mattered. And so the Torquemada episode ends with the bathing beauties holding up the lights of a menorah, a spectacular finish that could have been designed by Busby Berkeley.

Classic Hollywood was the custodian of gentile American life, which prizes wholesome sex appeal. Brooks’ Inquisition scene reminds us that Hollywood can turn anything into a song and dance full of infectious joy, and also that killing Jews for many centuries offered the world’s best entertainment value, unless you happened to be Jewish.

Even for Brooks there was a limit beyond which bad taste could not pass. He would never have dared satirize a Nazi death camp, since that hellish past was just a few decades gone, and really not gone at all. MAD did a parody of Hogan’s Heroes set in Buchenwald, but that was a single page in a magazine, not a big-screen spectacle. No one I know has ever seen Jerry Lewis’ suppressed Auschwitz movie The Day the Clown Cried, but I suspect it must be full of cringe-worthy schmalz rather than transgressive laughter—a worse sort of desecration.

Brooks came out of the 1950s when vulgar Jews like Lenny Bruce stuck in the craw of mainstream America. But the pull of WASPish assimilation, which Brooks always resisted, started to have degrading effects on Jewish comedy starting in the 1960s. Brooks’ fellow Show of Shows writer Woody Allen moved from the silly vulgar comedy of Bananas to faux-Ingmar Bergman “masterpieces” without a single laugh in them. Philip Roth went from Portnoy’s obscene antics to the cultured Upper East Side voice of the Zuckerman books, geared toward the public television crowd. There were still Jewish pornographers—Al Goldstein, the Powers brothers—but Roth had cleaned up his act. Despite the late-career efflorescence of Mickey Sabbath, Roth for the most part scurried into respectability, telling tales about lonely bachelors ensconced in deepest Connecticut.

Roth loved to battle righteous pricks (as he saw them). The Anatomy Lesson attacked a literary critic named Milton Appel—transparently Irving Howe, who had condemned Portnoy’s Complaint. Appel, Roth wrote, was “frozen stiff” in his “militant grown-upism,” a pompous hawker of “Loftier Values.” But despite his profane flourishes, Roth’s temperament was as stiff as that of his enemies. He substituted the holy cult of writing for the moralist’s sanctimony. Like Swede Lvov, he was a country squire dedicated to his work.

Roth’s heroes tend to be overgrown adolescents whose revolt against staid norms sputters out because they are too stringent and perverse to actually find pleasure in life. These men are wedded to a monotonous promiscuity that feels like hard work, not fun. Sex in Roth often “enslaves and isolates,” as the critic Ross Posnock observes. Getting laid becomes an ascetic endeavor—Mickey Sabbath is “the monk of fucking.”

Roth produced masterpieces like The Human Stain and American Pastoral, but these books also suffer from a pinched will to self-defense. Nearly every protagonist in later Roth is persecuted by someone who claims a moral high ground. Hamstrung by the indignation he felt at the feminists, the rabbis, and the puritanical book reviewers, Roth fell into the trap of claiming his own higher ground, the sacred territory of art. Instead of depicting human comedy with its unpredictable beauty, Roth turned programmatic, intent on showing why the critics were wrong. The rigid moralists he hated could never be upended by a polemic so self-serving and so devoid of wildness. Roth needed more vulgarity, not less.

By the ’90s the once coarse, crass American Jew had been reduced to a ghost in corduroy slacks with blow dried hair, musing about dental floss. Larry David and his partner in tepid comic narcissism, Jerry Seinfeld, presided over the shrinkage of Jewish comedy during the nine-year reign of Seinfeld, which became a zeitgeist show by doling out observational humor baby food and telling audiences that indulging one’s peccadiloes is the funniest thing in the world. Seinfeld coddled its quartet of comic actors, whose every gesture was meant to be hilarious. The show was Friends with chocolate babka, its stars a group of perpetual adolescents who never once uttered anything provocative. Seinfeld’s cushy trivialities went over big in America, where, at our worst, self-involvement is close to a national religion.

David then stepped out from behind the curtain to give us Curb Your Enthusiasm, which revolves around its star’s wish to be liked rather than deemed a jerk, even at his most irritating. Being Jewish according to David means annoying other people because you lack self-doubt. But the truly great comedians dig masochistically into self-doubt (as do some essential writers, like Kafka).

Howard Stern was, for a time, the anti-Seinfeld, his stock in trade the obscene and insinuating, until therapy tamed him. But the grandest vulgarian of them all was that nonpareil aristocrat, Gilbert Gottfried, with his unforgivable 9/11 and tsunami jokes. Gottfried’s strangulated, panicked-sounding yawp restored the honor of vulgar Jews everywhere.

We have to look to the work of Jewish stand-up artists like Gottfried the great, not Seinfeld or Curb Your Enthusiasm, for genuinely uncomfortable jokes. Louis CK and Dave Attell, milking their sad sack gripes, can lash out at themselves and their audience in startling ways. Sarah Silverman’s finest moment, and her most offensive one, was aimed straight at Jewish middle-class respectability. “I was raped by a doctor. Which is, you know, so bittersweet for a Jewish girl.”

It’s impossible not to squirm at this. Truly hard-hitting vulgarity isn’t easy to come up with, but Silverman did it with her rape joke. May we all have our pieties rocked in such a way, and may the grand tradition of Jewish vulgarity continue until Moshiach arrives.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.