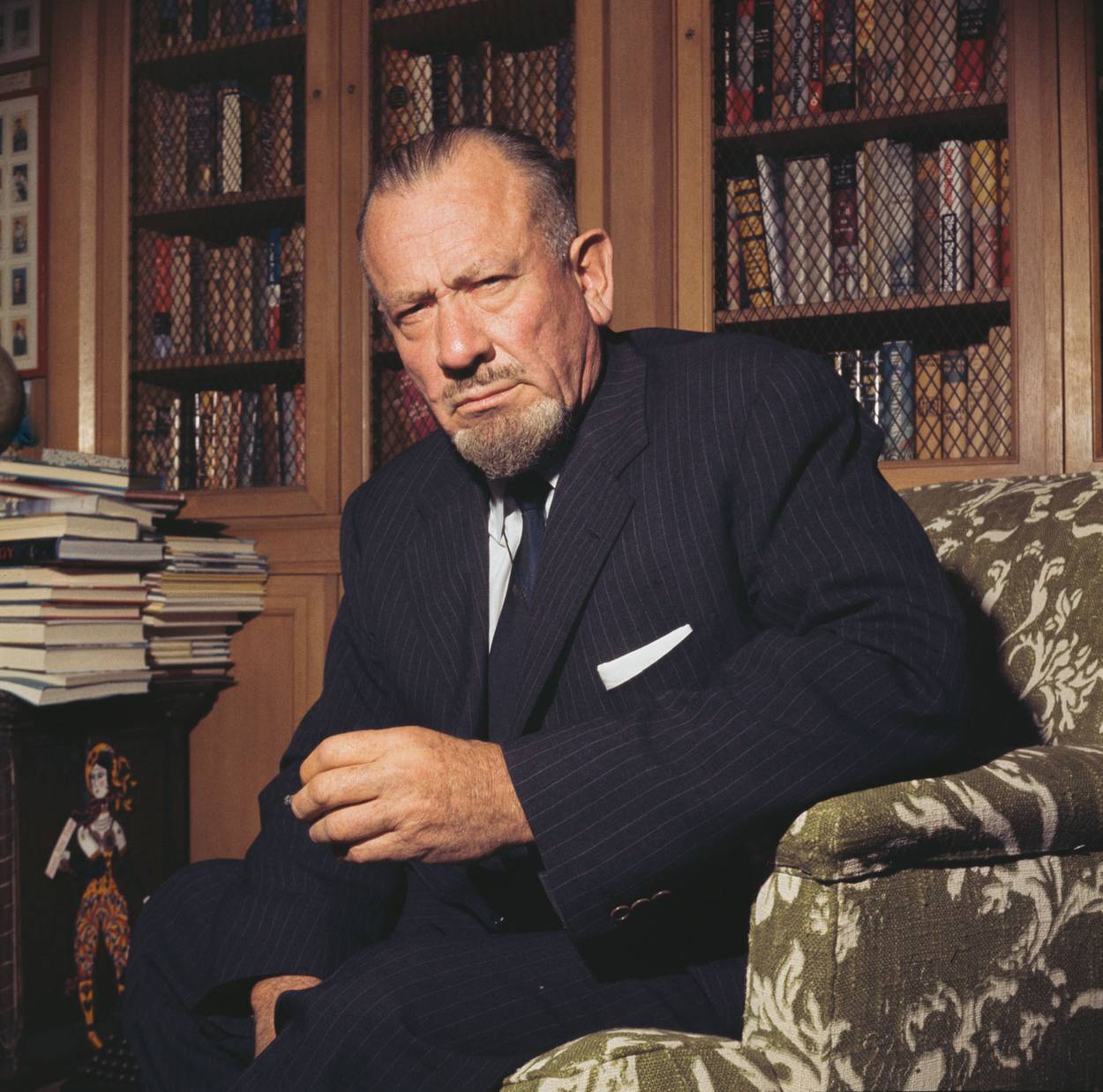

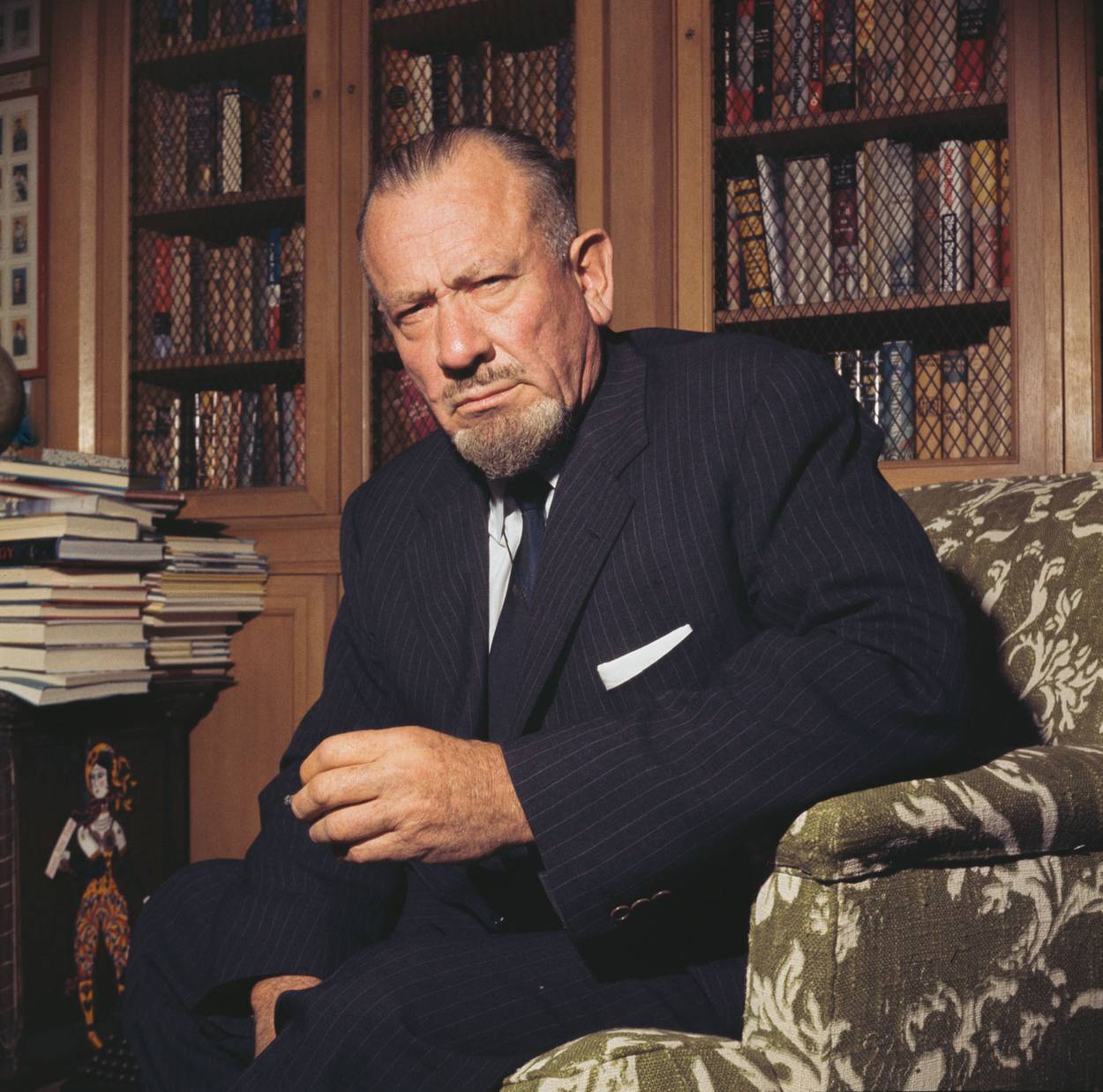

John Steinbeck’s Promised Land

The great novelist’s travels in Israel showed him what America had lost

Rolls Press/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images

Rolls Press/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images

Rolls Press/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images

Rolls Press/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images

Within days of his arrival in Tel Aviv, John Steinbeck, the recent Nobel laureate and one of America’s greatest bards, wrote back to the States singing Israel’s praises. “This country boils and burbles,” he told his editor at New York Newsday, “squirms and gallops with energy. If there is such a thing as a boisterous ferment, it is here. In most countries I have seen and lived in, everything that can be done has been done. In Israel, in spite of its 4,000 years of history, everything is to be done and as though for the first time. It kind of bears out what I have always felt—that only those people who have nothing to do and no place to go are tired. I see no evidence of weariness here.”

In his 1966 jaunt across Israel, Steinbeck found what he felt was lacking back home. He encountered a people flush with patriotism, loyalty, and enthusiasm for military service—a stark contrast to what he saw in the youth of the United States, who, he wrote, were “burning draft cards because war in Vietnam was intolerable.” As Jay Parini, Steinbeck’s biographer, noted, the great novelist “was intent on contrasting Israel’s energetic vision of itself with America’s loss of vision.”

What did Steinbeck see in Israel beyond a country with a vision—a country full of brave and energized young people fighting for their future? In part it was America’s own lost promise. After visiting Israel’s border with Jordan, he noted that “the forest [of Israel] stops at the barbed wire, and beyond is that treeless waste, barren, sullen, intractable.” Here, in the hills of Israel, was that great wilderness that once personified the young and vibrant United States. To Steinbeck, America was no longer such a wilderness—was not a country that bordered barrenness but that had become barren itself.

This sense of American decline permeates East of Eden, Steinbeck’s 1952 masterpiece. The novel takes its title and structure from the story of Cain and Abel in Genesis, a narrative that tells the story of the sons of Adam and Eve. Cain kills Abel for reasons that the biblical text leaves mysterious, and the story concludes with Cain’s departure from Eden. “And Cain went out from the presence of the Lord, and dwelt in the land of Nod, east of Eden.”

Steinbeck’s sprawling, 500-page opus can be understood as an elaborate midrash on this biblical story. In the novel, Steinbeck turns these two competing brothers into two families, the Hamiltons and Trasks of California’s Salinas Valley. After achieving an Edenic life in California’s Salinas Valley, the Hamiltons and Trasks lose their legacies through dissension and bitterness, ultimately reenacting the fall of man and expulsion from Eden.

This bitter legacy of self-doubt and self-destruction is then repeated by the next generation—particularly by the twins of the Trask family, Aron and Caleb (Cal). Aron is the “good son” and Cal the “bad son,” and at the story’s end Cal is made to understand that the family legacy of evil can be overcome by an act of will.

At the novel’s dramatic conclusion, Steinbeck invokes the biblical term timshel, a word that he interprets as the human ability to control our baser nature. The translation of that Hebrew word from Genesis provided Steinbeck with one of the novel’s central themes: the development of “individual responsibility and the invention of conscience.”

Mid-1960s America, in Steinbeck’s view, lacked such timshel totally—was a society in free fall, a country lacking the will to overcome adversity and dissension and act forcefully. Steinbeck supported American involvement in Vietnam but was critical of the manner in which the war was conducted. As Steinbeck grew increasingly supportive of America’s war in Vietnam, he felt increasingly alienated from the student antiwar movement and from most of his literary colleagues—people who, in his view, lacked an inspiring vision of America’s future.

Steinbeck also saw Israel’s military prowess as a challenge to Soviet support for the Arab states, which provided additional motivation for his enthusiasm for the young country. He wrote to Jack Valenti, Lyndon Johnson’s special assistant, that “the Israelis are the toughest and most vital people I have seen in a long time,” and that “[t]heir army is superb.” Israel, Steinbeck believed, should be seen as a crucial ally of the United States. Obvious but unstated in that letter, was Steinbeck’s view that America and its military lacked this toughness and vitality completely.

What did Steinbeck see in Israel beyond a country with a vision—a country full of brave and energized young people fighting for their future? In part it was America’s own lost promise.

Steinbeck’s trip to Israel was the result of a journalistic assignment for Newsday, the Long Island newspaper founded in 1940 and still published today. Steinbeck was a seasoned journalist, and his early reporting on migrant workers during the Depression inspired some of his most successful fiction, including The Grapes of Wrath, published in 1939.

In the early 1960s, Harry Guggenheim, Newsday’s owner, asked Steinbeck to write a regular column for the newspaper. Appearing intermittently from November 1965 through May 1967, these occasional Newsday columns proved a fruitful form for Steinbeck. He was given the freedom to write about subjects that caught his attention during his travels, with no deadlines and no rigid schedule.

In addition to his profound interest in the Hebrew Bible, Steinbeck had a family connection to the history of Israel. Both his paternal grandfather and his great-uncle had been members of Mount Hope, a small group of German and American Protestants that established an agricultural mission near Jaffa in 1853. The Steinbeck men were Germans married to American women. In Ottoman Palestine they hoped to convert local Jews to Christianity.

In January 1858, a dispute with local Arabs over a stray cow led to a vicious attack, during which Steinbeck’s grandfather was killed and his grandmother’s sister and her mother were raped. The attacks caused a diplomatic flare-up, with the Prussian and U.S. governments demanding justice from the Ottoman authorities. Soon after the attack, the survivors of the massacre left Jaffa for America, where they settled first in New England and later in California. In American diplomatic history, this incident is known as the 1858 “Outrages of Jaffa.”

Steinbeck considered this tragic family history a likely source of his initial reluctance to visit Israel. “I’ve started for there several times; never made it,” he wrote. “I wonder if I have an unconscious reluctance because of what my great-grandfather tried to do there in the 1840s.”

During the two months that Steinbeck spent in Israel, he was constantly on the move. He enjoyed traveling through the Negev, which reminded him of Nevada and parts of Texas. On a number of occasions, he met with Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek, who was aware of Steinbeck’s ancestral connection to the “Outrages of Jaffa” incident of 1858, and arranged for the couple to visit the few remaining buildings from the original settlement.

The articles Steinbeck produced from Israel for Newsday showered the country with praise, even while registering its challenging history and the fragility of its very existence. “Israel, this little area of the world, here the incredible texture of human endurance and the tough inflexibility of human willpower was in evidence. You can search the world over and you’ll not find Israel’s equal for a stinking past of heroic proportions. The present is even worse if that is possible: surrounded by enemies dedicated to her destruction.”

And yet, in that terrible past and challenging present, Steinbeck saw nothing but the Promised Land.

Shalom Goldman is Professor of Religion at Middlebury College. His most recent book is Starstruck in the Promised Land: How the Arts Shaped American Passions about Israel.