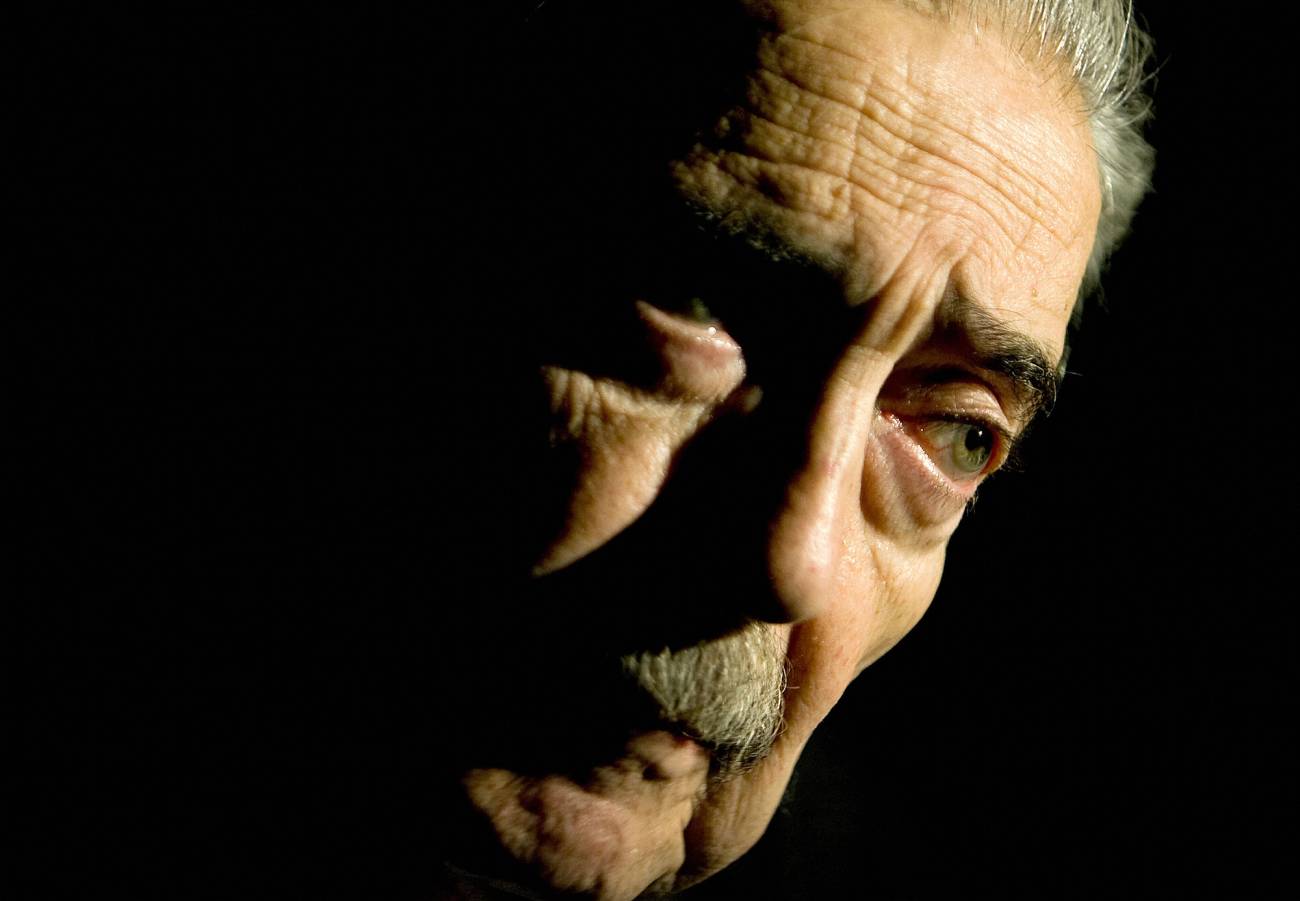

Juan Gelman: Four Ladino Poems

A new translation

Alfredo Estrella/AFP via Getty Images

Alfredo Estrella/AFP via Getty Images

Alfredo Estrella/AFP via Getty Images

One of the most distinguished Latin American poets of the 20th century, Juan Gelman (1930-2014) is an emblematic figure connected with the Dirty War. A Yiddish speaker from birth, Gelman became a left-leaning journalist whose voice antagonized Argentina’s military junta. He was forced into exile around the time his son and pregnant daughter-in-law were kidnapped by the police. They are among the 30,000 desaparecidos, a considerable number of whom were Jewish.

In exile (Spain, France, Mexico, among other places), Gelman, an agnostic, found out that his daughter-in-law had given birth in captivity to a child who had been adopted by a military family. He found solace in the biblical prophets, the Hekhalots, the medieval Spanish poets Samuel Hanagid, Solomon ibn Gabirol, Yehuda Halevi, the work of Spanish crypto-Jewish mystics Santa Teresa de Ávila and San Juan de la Cruz, and the verses of kabbalists like Isaac Luria. Confessedly, what attracted him to all of them wasn’t their theological worldview but the genuine, heart-felt explorations each of them made of exile, both physical and spiritual.

Soon after, as a way to cope with his ongoing displacement, Gelman, from the 1980s onward, rewrote scores of these sources in his own style. He wasn’t interested in translating them; his objective was to flat out appropriate them, projecting their echoes into our modern sensibility. He also taught himself Ladino in order to write a full-length volume, which he called dibaxu, a Ladino word meaning “under.” In this task, his inspiration was Clarisse Nikoïdski, a novelist in French and poet in Ladino, whose poems remain unavailable in English.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I too experienced exile from my own daily circumstance, like millions of others around the globe. To cope, I delved into Gelman’s Ladino poetry and was quickly intrigued by his recreations. The result are my own archeological translations in Otrarse: Ladino Poems of Juan Gelman, due out this November from University of New Mexico Press with an introduction by Ilya Kaminsky.

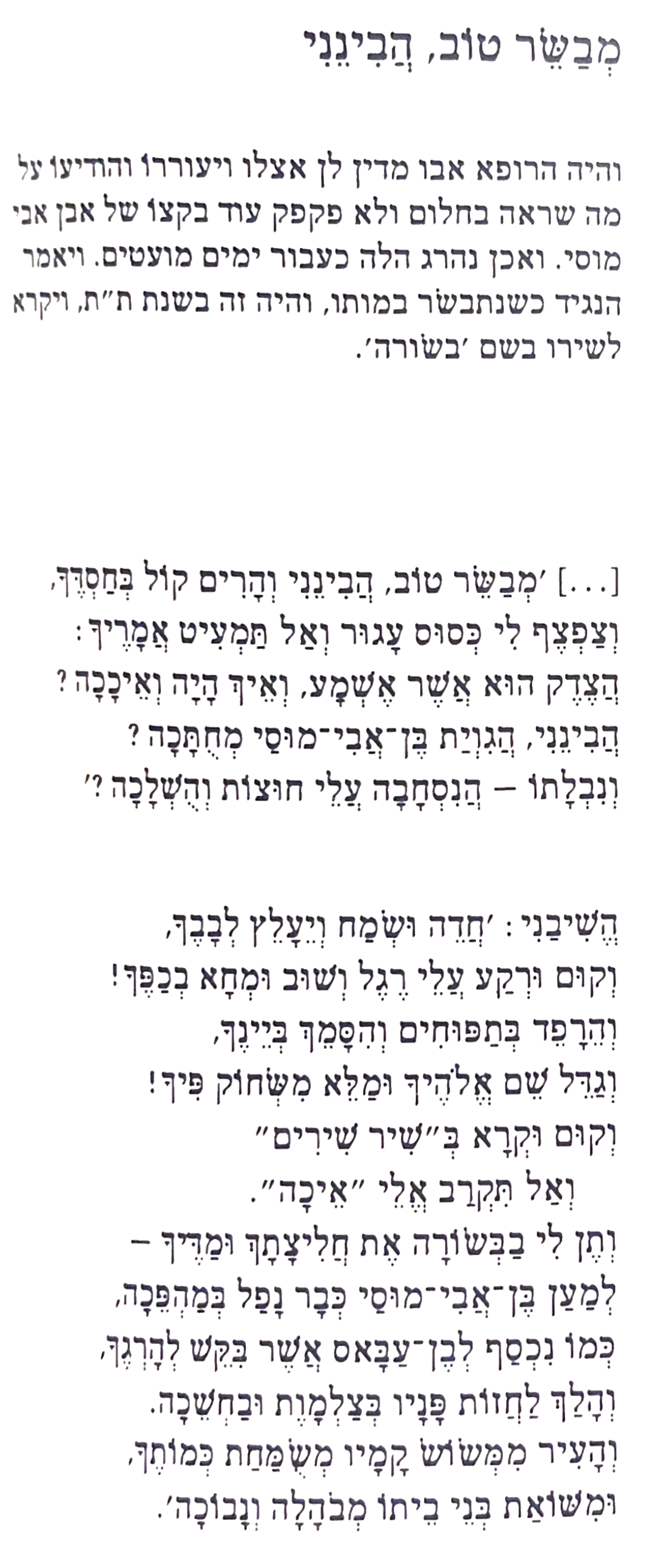

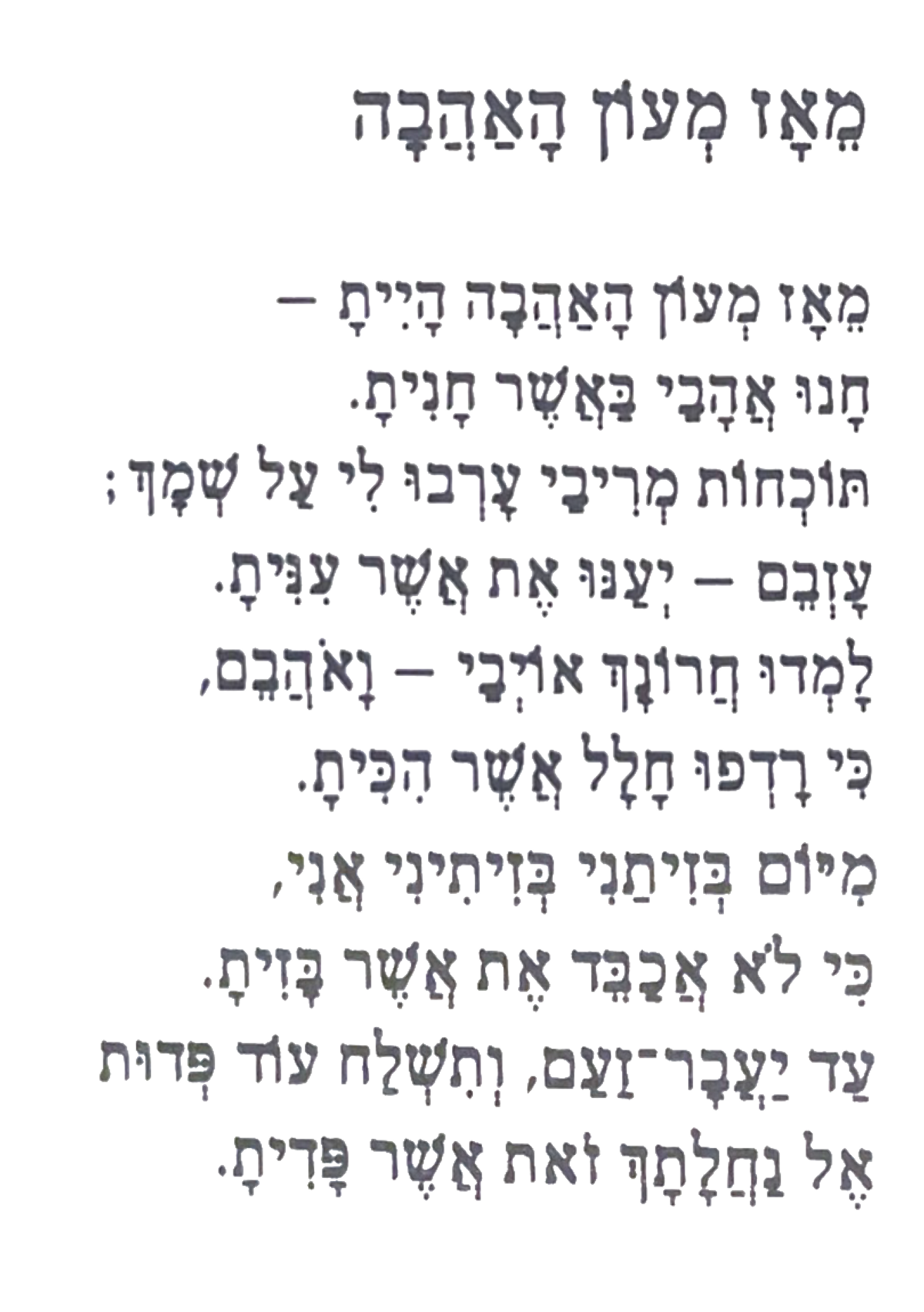

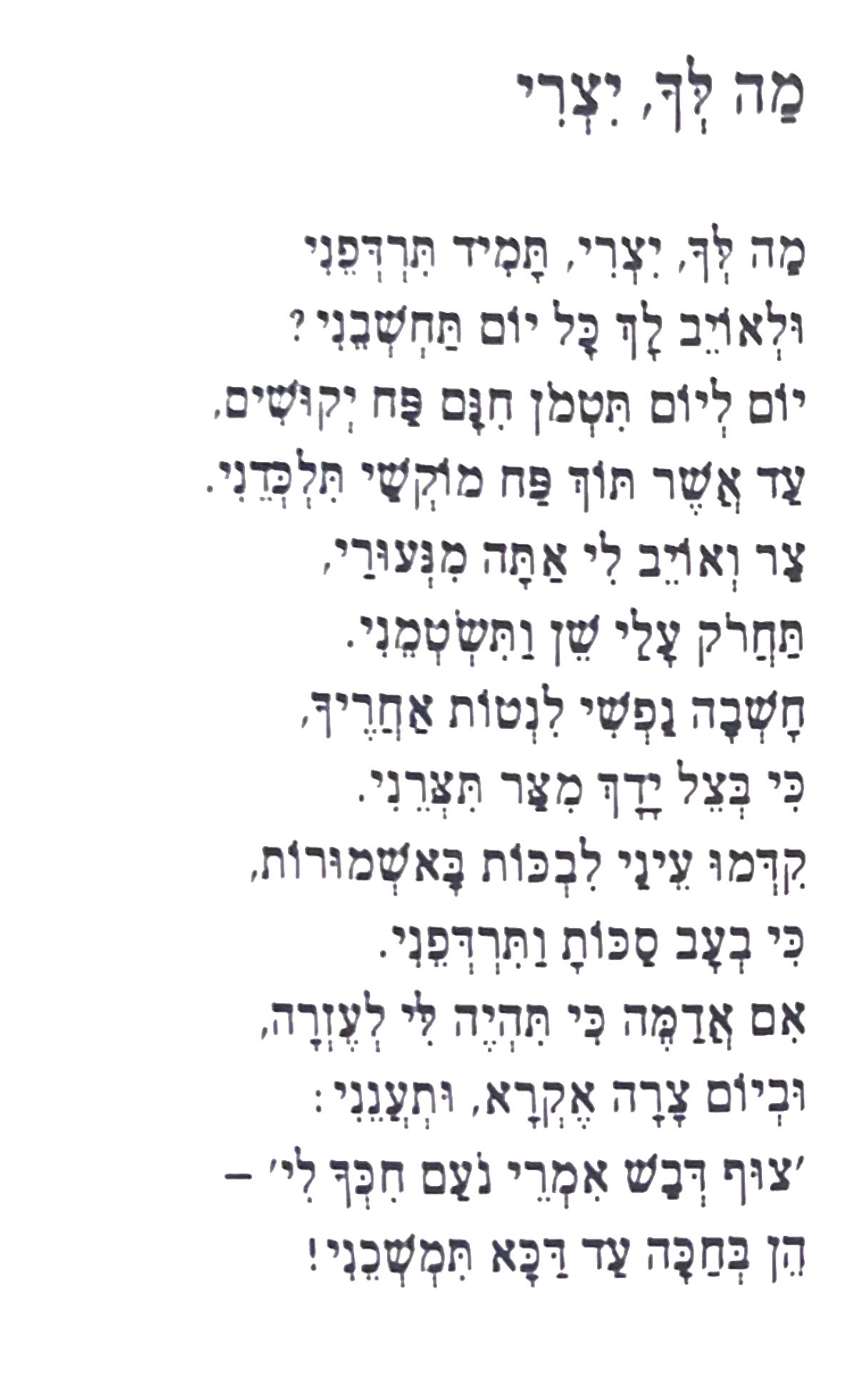

Here are four sample translations. One poem refashions an elegy by Samuel Hanagid (“On Learning of His Enemy’s Death”), another reinvents a poem by Yehuda Halevi (“The Home of Love”), and a third re-imagines a eulogy by Isaac Luria (“To His Self”). The last one is poem X from dibaxu. My English translations are accompanied by Gelman’s Spanish original and the Hebrew source in the first three cases (T. Carmi’s The Penguin Book of Hebrew Verse, 1981), and by Gelman’s Ladino in the fourth.

Juan Gelman received the prestigious Cervantes Prize in 2007. —I.S.

I dreamt your death/later on

dreamt at your death/ibn abi musa:

you fulfilled my two dreams!/

did they mutilate your body/did they

drag your fresh corpse through the streets?/

my feet dance and my hands clap/

I celebrate with apples/with wine

I rinse the roof of my mouth/my old wound/

did they torture you/destroy

your soul with

the scraps of the mangled flesh?/

today I will not read the lamentations/

today I will read the song of songs/

the bride’s sudden appearance/

beautiful like the moon/

radiant as the sun/terrifying

as an army ready to battle/

I am removed from your face/blurred/sinking/

I drink in your bride’s cups/

her breasts of inextinguishable liqueur/

I kiss the wheat growing in her womb

surrounded by white lilies/while you/

ibn abi musa/

visit the stench of the tomb/

you discover the night in the pit/

you have only the hissing of serpents

for company in your journey to ashes/

I am here/I put on perfume/change

into festive cloths/recalling

the fortress in ruins

where I once thought about the generals/

soldiers/builders/

ravishers/slaves/masters/

the powerful/beggars/

hired mourners/the newly wed/

parents and offspring/

who once inhabited

the earth/now housed

under the ground/they passed

from elevated light to dust/like you/

ibn abi musa/

like I will pass/

like the hatred that bound us/

its rages/its terrors/

yo soñé con tu muerte/después

soñé en tu muerte/¡ibn abi musa:

mis dos sueños cumpliste!/

¿mutilaron tu cuerpo/arrastraron

tu ya cadáver por las calles?/

mis pies danzan y mis manos aplauden/

me corroboro con manzanas/con vino

baño mi paladar/mi vieja llaga/

¿te torturaron/te

destrozaron el alma con

las dos miserias de la carne rota?/

hoy no leeré los lamentos/

hoy leeré el cantar de los cantares/

la súbita aparición de la esposa/

bella como la luna/

brillante como el sol/terrible

como ejército en orden de batalla/

me aparta de tu rostro/oscuro/hundiéndose/

bebo en las tazas de la esposa/

sus pechos de licor inextinguible/

beso el trigo que crece en su vientre

rodeado de azucenas/mientras vos

ibn abi musa/

visitas el hedor de la tumba/

te enterás de la noche del pozo/

sólo un silbido de serpientes

acompaña tu viaje a las cenizas/

yo estoy aquí/me perfumo/me ciño

las ropas de la fiesta/pienso en

la fortaleza en ruinas

donde una vez pensé en los generales/

los soldados/los constructores/los

destructores/los esclavos/los amos/

los poderosos/los mendigos/

las plañideras/los recién casados/

los padres y los hijos/

que alguna vez se alojaron encima

de la tierra/y se alojan ahora

en la tierra/pasaron

de la alta luz al polvo/como vos/

ibn abi musa/

como yo pasaré/

como el odio que nos ató/

con furias/sus terrores/

you became my nest of love/and my love

lives where you live/the enemies

tormented me/let them be/ let your ire be/

as long as I don’t find my path to you/

my bones tremble embracing a stranger/

the foreigner of his own skin/

let it be/

as long as you don’t absolve my pain/

seat me/redeem me/

rescue me from myself/

tu hiciste nido de mi amor/y mi amor

vive donde vivís/los enemigos

me atormentan/que sean/sea su ira/

mientras no encuentre mi camino hacia vos/

mis huesos tiemblan sosteniendo a un extraño/

al extranjero de tu piel/

así sea/

mientras no absuelvas mi dolor/

me sudes/me redimas/

me rescate de mí/

what is the matter? why do you

always pursue me as an enemy?/

you set hidden traps for me?/you catch me in my own snare?/

nail your fever to my flesh?/

my soul dreamed of following you/

in sheltering in the shade of your hand/still/saved under the shadow

by your hand/but eyes awoke

before the night watch/you call me

nothing and I become nothing/

I/who is destined to the sweetness

of your words/I am an orphan/

witness how fast I shall sleep in the dust/

you will not find me when you look for me/

who will then throw your bait?/

hooking his palate/

you will push him into his fate?/

if I lie down/I ask

when shall dawn come/

if I rise up/I ask

when shall night arrive/

I hurry time to see you/

exiled from myself/

like the Creator of all creation/

¿qué pasa?/¿por qué cada día

me perseguís como a enemigo?/

¿me tendés trampas?/¿me acosas?/

¿clavás tu fiebre en mi carne?/

mi alma soñó en seguirte/

en quedarse a la sombra de tu mano/

quieta/salvada de dolor

por tu mano/pero me hacés llorar

ante el guardián nocturno/me llamás

nada y en nada me convierto/

yo/el destinado a la dulzura

de tus palabras/soy el huérfano/

mirá que pronto dormiré en el polvo/

cuando me busques no me encontrarás/

¿a quién arrojarás tu anzuelo entonces/

le engancharás el paladar/

lo tirarás a su destino?/

si me acuesto/pregunto

cuándo la autora llegará/

si me levanto/pregunto

cuándo la noche llegará/

apuro al tiempo para verte/estoy exiliado de mí/

como el Creador de todo lo creado/

you utter words with trees/

they have singing leaves

and birds

gathering sun/

your silence

awakens

the world’s

shrieks/

dices palabras con árboles/

tienen hojas que cantan

y pájaros

que juntan sol/

tu silencio

despierta

los gritos

del mundo/

dizis avlas cun árvulis

tenin folyas qui cantan

y páxarus

qui djuntan sol/

tu silenziu

disparta

lus gritus

dil mundo/

Ilan Stavans is the Lewis-Sebring Professor of Humanities and Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College, the publisher of Restless Books, and a consultant to the Oxford English Dictionary. His book Sabor Judio: The Jewish Mexican Cookbook (Ferris & Ferris, co-written with Margaret Boyle), will be out in October.