Judaism vs. Cubism in Paris

Was being a ‘Jewish painter’ detrimental or ‘limiting’ to an artist’s work and reputation? The case of Chagall, Modigliani, and Picasso.

Marc Chagall’s first teacher was Yehuda Pen, a well-trained academic artist, who later on had a habit, especially when exasperated, of calling Chagall’s modernist art “Shagalovshchina,” which can be roughly translated into English as “Chagallesque,” except the suffix in Russian is much more derogatory. Even when Chagall was a small boy, ogling Pen’s paintings at the artist’s studio in his native Vitebsk, Belarus, he had apparently already decided that his future teacher’s superrealistic style was not his cup of tea. What strongly appealed to him, however, were Pen’s depictions of their town and its unabashedly Jewish characters, which the boy tried to reproduce in his own drawings. Chagall’s early worship of his teacher is made clear in his 1923 autobiography, My Life: “How many times I was ready to beg him standing on the threshold of the school: ‘I don’t need fame, only to be like you, a modest craftsman, or to have my pictures hang like your pictures, on your street, in your house, next to yours. Just let me!’”

For the rest of his life Chagall, like Pen, remained defiantly Jewish in his choice of subject matter. As one of his biographers, Jonathan Wilson, aptly put it, he simply “continued to paint in Yiddish.” And yet, the same biographer revealed a deep critical unease about how this Yiddish character of Chagall’s paintings may have affected the artist’s overall standing and legacy. “Chagall’s brilliant harnessing of his Yiddish past to modernist techniques could have only a restricted influence because his subject matter collected around beautiful losers in a dying culture,” Wilson wrote. “Chagall, whether he believed that he was doing so or not, sneaked Yiddish culture into twentieth century painting through the back door. … Sadly, Chagall’s genius spawned a host of artists who specialized in Jewish kitsch, whereas Picasso’s had an impact on almost every great painter who came after him.”

Wilson’s assessment is eerily reminiscent of one of the earliest judgments on Chagall rendered by Anatoly Lunacharsky, who would become the first Bolshevik commissar of education. Writing for a Kyiv newspaper in 1914 about Russian painters in Paris, he described Chagall as “a young Hoffmann from the Vitebsk slums” and “an interesting [but] sick soul, both in his joy and his melancholy.” “The genre he chose for himself,” Lunacharsky declared, “is madness. ... All the elements of his fantasy are borrowed from the boring, repressed, clumsy life of poor Litvak Jews.” While admitting that the young painter was nevertheless worth following, Lunacharsky hastened to add that Chagall was doomed not to have any followers: “For others to follow in the same path would be a disaster.”

In other words, according to the future commissar of education, having flying Jews was crazy both because they were flying and they were Jews, but Chagall could somehow pull it off because he was an artist with a poetic soul. Furthermore, Lunacharsky warned, Chagall’s impact on other artists would always be not just very limited but also quite calamitous. Since then, this somewhat contradictory sentiment has become the common critical marker of anxiety among Chagall scholars and biographers, helped along, no doubt, by influential cultural trendsetters like Robert Hughes, who undercut his own sizable admiration of Chagall, in his tribute written soon after the artist’s death in 1985, as “the quintessential Jewish painter of the twentieth century” by rebranding him some two decades later the “Fiddler on the Roof of Modernism.”

Yet I would strongly challenge the oft-stated popular wisdom that being a “Jewish painter” is detrimental or “limiting” to an artist’s work and reputation. On the contrary, in Chagall’s case, I believe that his Jewish identity was precisely what cemented his reputation and influence and allowed him to compete with the likes of Picasso and Matisse at a time when very few artists could. In order to prove my point, I will compare Chagall’s earlier years in Paris with those of Amedeo Modigliani, a contemporaneous and wildly talented Jewish painter who was not from the Pale of Settlement and who did not have the same option of being able to capitalize on his “otherness.” It is impossible, of course, to imagine what would have happened in the long run if Modigliani, like Chagall, had been fated to live a much longer and much healthier life. And yet, looking at the two artists side by side during the years they rubbed shoulders in Paris as two young and evolving painters is very telling.

Modigliani was born in 1884; Chagall three years later. Chagall’s family in Vitebsk was quite poor. Modigliani’s family in Livorno used to be reasonably well-off but was impoverished by the time of his birth. Vitebsk, in the Russian Empire’s Pale of Settlement, was largely Jewish: According to the 1897 Census, out of the total population of 66,000, Jews accounted for roughly 52%. Most of them were religiously Orthodox and spoke, almost exclusively, Yiddish. In the early 1800s Livorno had one of the more vibrant Jewish communities in Italy, but by the turn of the 20th century the Jewish population of Livorno had dwindled to about 3,000 out of 100,000 inhabitants. Some Sephardic Jews still spoke Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) at home, but most, like Modigliani’s family, spoke Italian. Unlike their Eastern European counterparts, Jews in Italy in the second half of the 19th century enjoyed the same rights as their gentile peers, and there were no pogroms.

Critic Robert Hughes undercut his own sizable admiration of Chagall as ‘the quintessential Jewish painter of the 20th century’ by rebranding him two decades later the ‘Fiddler on the Roof of Modernism.’

Modigliani’s assimilation is constantly stressed by his biographers and other art scholars. The traditional critical narrative about the difference between being an Eastern European Jewish painter and one from Western Europe usually also emphasizes the personal and professional benefits of assimilation. Typical in this respect is the assessment offered by one of Modigliani’s biographers, Jeffrey Meyers: “The eastern European artists—Chagall, Zadkine, Lipchitz, Paskin, Kisling and Soutine—were thought of as Jews rather than Bulgarians, Lithuanians, Russians or Poles, but Modi was always considered quintessentially Italian. … Assimilated Italian Jews felt equal to or even intellectually superior to their Christian neighbors, while poor eastern European Jews, confined to the ghetto, living in remote villages or shtetls, and victims of persecution often felt distinctly inferior.” Meyers then, quite predictably, given his positive bias toward assimilation, goes on to warn us that it is erroneous “to claim (and limit) Modigliani as a Jewish artist.” And yet, as we will see, Modigliani himself appeared at times to strongly disagree with this assessment.

Modigliani and Chagall came to Paris when they were roughly the same age: Modigliani in 1906, when he was 22, and Chagall in 1910, when he was 23. They both first settled in Montmartre and then moved to Montparnasse. Two years after he moved to Paris, Modigliani painted his only known portrait where the sitter is directly identified as Jewish—“The Jewess” (“La juive,” 1908).

It is one of Modigliani’s most ambiguous, in-the-eyes-of-the-beholder, paintings, as is obvious from contradictory descriptions offered by his various biographers and art critics. Thus Meryle Secrest in Modigliani: A Life calls it a “curious work … on the verge of caricature.” “Its title and the manner of its depiction,” writes Secrest, “would suggest that some self-loathing was involved.” Similarly, Jeffrey Meyers, in his biography, labels it “ugly and repulsive” and likewise states that it smacks of “Jewish self-hatred.” On the other hand, Mason Klein, in Modigliani: Beyond the Myth, finds the face of the Jewess to be “solemn” and “haunting,” while Tamar Garb, in the same volume, describes the portrait as “a fin-de-siècle fantasy of rouged lips, sultry sensuality, and fashionable femininity in keeping with contemporary cultural stereotypes and ethnic assumptions.”

As Jeanne Modigliani, the artist’s daughter, points out, Modigliani was, in fact, “enormously attached to this picture,” making it even less likely to be, in his mind, a self-loathing caricature. From what we know, Modigliani often introduced himself to new people by emphasizing his Jewishness, often with the declaration “Je suis Modigliani, juif.” Anna Akhmatova, a young Russian poet whom he met and became infatuated with in 1910, remembered years later that at some point Modigliani all of a sudden felt compelled to utter: “I forgot to tell you that I am Jewish.” Though not Jewish, Akhmatova, interestingly enough, possessed an irregular beauty quite reminiscent of Modigliani’s “Jewess.”

The critic Mason Klein goes as far as to suggest that while Modigliani employed different strategies from Chagall to reveal his Jewishness, his need to do so was in essence almost as powerful as Chagall’s: “Instead of expanding his range of subject, he restricted himself to portraiture; rather than assimilate, Modigliani ‘unmasked’ his Jewishness by assuming the ideological position of the pariah.” Klein then goes on to compare Chagall’s and Modigliani’s portrayal of Jewish (or Jewish-looking, in Modigliani’s case) musicians—Modigliani’s “The Cellist” (1909) and Chagall’s “Green Violinist” (1923-4). He writes: “While Chagall presents us with a musician whose exuberance exclaims a visual liberation, Modigliani’s somber cellist conveys the artist’s reflective connection to music, and perhaps the nostalgic silence just as the bow finishes its chord.”

The two musicians are a perfect metaphor, it would seem to me, for Chagall’s and Modigliani’s senses of themselves as Jews. While the cellist may be a Jewish pariah he is still located within the established Western tradition of classical music. Chagall’s violinist, on the other hand, is an unabashed Jewish fiddler who is playing, and often improvising, original Eastern European Jewish music—klezmer.

Modigliani seems to have been well aware—and in fact quite jealous—of this distinction. His closest friend in Paris was another Belorussian Jew whose native language was Yiddish, Chaim Soutine, and he often hung around other Jewish artists from the Pale. Meyers, who worries about “limiting” Modigliani by referring to him as a Jewish painter, provides in his biography of the painter a striking glimpse of what sounds like “Yiddish envy,” when Modigliani—apparently with the beforehand help of a friend who had translated and transliterated the Yiddish text for him—one evening “took a newspaper out of his pocket … [and] read, in Yiddish, an article praising him.” According to Léon Indenbaum, another Jewish artist from Belarus who apparently witnessed it, Modigliani “was visibly moved.”

Jeanne Modigliani tells us that soon before he died, her father visited a friend, “asked for something to drink and then began to cry, singing under his breath a Jewish song.” She suspected that it was “probably the Kaddish, the prayer for the dead.” And yet, by comparing Modigliani directly to Chagall and Soutine, Jeanne Modigliani also drew a sharp distinction between: “Chagall and Soutine, whom even the most convinced ‘Judaizers’ admit with no hesitation, had a completely different quality, both in their way of living and their way of painting.” The difference was, according to her, that Modigliani was, after all, “a Mediterranean Jew.”

***

What Modigliani envied, Chagall had in spades. While in Paris, he mentally and artistically never moved out of the Pale in general and Vitebsk in particular. In his first year in Paris, Chagall painted “The Wedding,” depicting a young Jewish couple in Vitebsk accompanied by their families, rebbes, and klezmer musicians while a female storekeeper is trying to entice them to step into her “lafka.” In the span of the next three years came his three other early masterpieces—“I and the Village” (1911), an earlier version of the “Green Violinist” (“The Violinist,” 1913), and “Over Vitebsk” (1914).

It is crucial here to understand the larger artistic principle that Chagall and Modigliani shared: Unlike many of their peers, neither one wanted to be associated with any of the contemporaneous “isms,” including cubism. Pablo Picasso had preceded them to Paris by several years; he was just three years older than Modigliani, and six years older than Chagall, but in terms of his established reputation and following he was light years ahead of them both. Modigliani’s fight for his artistic independence from Picasso was more personal than Chagall’s, since he and Picasso knew each other quite well. In Artist Quarter: Reminiscences of Montmartre and Montparnasse, Charles Beadle, who socialized with Modigliani in Paris, remembered the artist’s vehemence about staying unique: “Once when I asked him what he called his ‘manner,’ he retorted haughtily: ‘Modigliani! When an artist has need to stick on a label, he’s lost!’”

While often critical of cubism, Modigliani nevertheless considered Picasso not just a mentor of sorts but also a measuring stick. One of his other friends remembered that once, when Modigliani did not like a painting he just completed, he lamented: “Ah, that’s no good. … Just a misfire. Picasso would give it a good boot if he saw it.” Picasso liked some of Modigliani’s work and purchased several of his paintings, which he was not above covering with his own thick oils when he ran out of clean canvas.

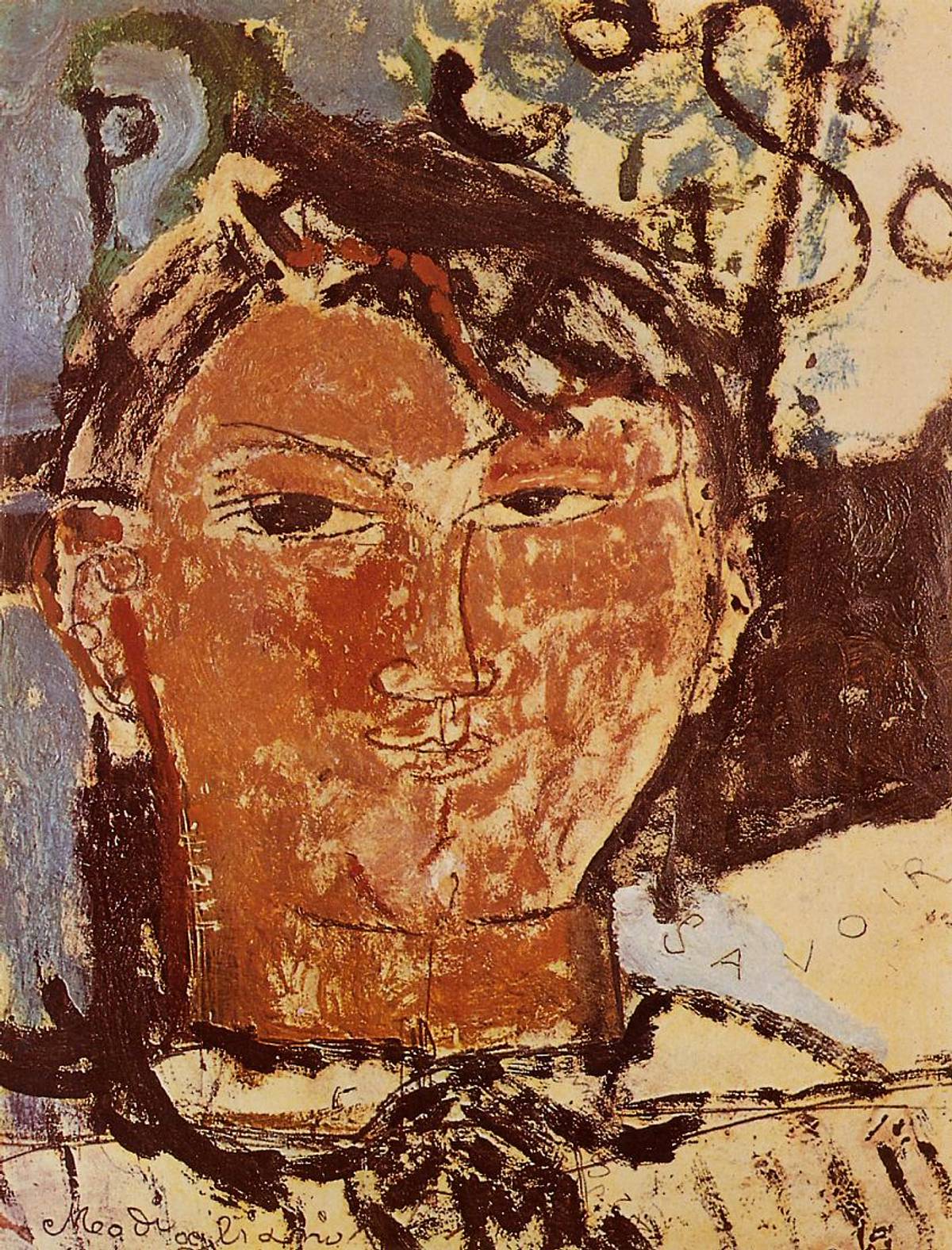

A portrait Modigliani painted of Picasso in 1915 seems to have reflected his complicated feelings toward the founder of cubism—and may, unlike his “Jewess,” actually border on caricature. On it, the word “savoir” (to know; knowledge) is scratched to the right of the painter’s neck in a possible dig at Picasso’s self-assumed superiority and omniscience.

In order to establish his own artistic voice, Modigliani went back and forth between painting and carving sculpture in stone, hoping to find a medium and a form where he could be unique. He also reached out to many other cultures, among them, as pointed out by Kenneth Wayne in Modigliani and the Artists of Montparnasse, “African art, Cambodian art, Egyptian art, Roman art, Greek art … the kabala and Jewish mysticism.” Modigliani’s experimentation with the “otherness” is of course quite reminiscent of Chagall’s except that, in Modigliani’s case, none of this “otherness” was quite his own.

Modigliani did manage to bravely remain “a pariah” by sticking to his own artistic principles, and, yet, as Meyers succinctly concludes, he and Picasso were destined forever to remain “unequal rivals”: “Modi could not compete with [Picasso’s] protean changes in style and his overwhelming genius.”

Chagall of course also competed with Picasso and, likewise, enjoyed undercutting the more famous Spaniard and his cubism. In Chagall’s 1923 autobiography he remembers thinking when in Paris: “Let them eat all they want their square pears on their triangular tables.” (His most biting quip about Picasso himself—“What a genius, that Picasso. It’s a pity he doesn’t paint”—did not occur until already after WWII, by which point their relationship was also colored by their contrasting attitudes toward the Soviet Union.) While in Paris in these early years Chagall, unlike Modigliani, never actually socialized with Picasso; but Picasso was still constantly on his mind. In 1914 Chagall even made a drawing that included the following text in Russian: “I am tired of Chagall. Thinking Picasso.”

That Picasso loomed so large in Chagall’s psyche should not come as a surprise. Like Modigliani, Chagall was undoubtedly painfully aware from the start that in his competition with Picasso, the Spanish painter would probably always hold sway. And yet, unlike Modigliani, he had unique tools at his disposal to become more than just a proud pariah. By emphasizing his strong identification with his native Yiddish culture, Chagall appears to have hit upon a very astute—albeit to some counterintuitive—understanding of what could best place him in a position to even compete with Picasso. Judaism was Chagall’s “ism”: Being a quintessentially Jewish/Yiddish artist while at the same time a daring non-realist made him in many ways as path-breaking and original as the pioneer of cubism.

This is not to suggest that his choice was largely pragmatic. Chagall obviously had an utterly genuine obsession with all things Yiddish. When Lunacharsky kept asking Chagall in Paris why he was painting the way he was, Chagall kept insisting that he simply “could not help it,” “could not do otherwise,” “absolutely had to do it this way,” as if, like a romantic poet, he was guided by divine artistic inspiration, the force of which he could not resist. Given the dreamlike nature of his early paintings, some readers of his conversation with Lunacharsky may have also detected Freudian notes in these responses. His son-in-law, Franz Meyer, while acknowledging that “Chagall took no interest whatsoever in Freud at that time,” remembered the artist actually saying that “psychoanalysis was the scientific parallel to his early works.” In his 1923 autobiography, Chagall underscored how spontaneous and “soulful” his art was in words that smacked of both the “divine” guidance and psychoanalysis:

I, personally, am not so sure that any theory is such a great thing for art. Impressionism, Cubism, they are equally alien to me. I believe that art is first of all how your soul feels. And one’s soul is sacred in all of us walking on this sinful earth. One’s soul is free; it has its own sense, its own logic. And only there no falsehood exists where the soul, by itself and organically, achieves the stage which in literature is commonly called irrational.

Chagall’s love for all things Yiddish also stemmed from him being an unabashed “nationalist,” proud of what Jews had contributed to civilization. “If I were not a Jew … I wouldn’t have been an artist or would have been a different one,” he declared in 1922. “I personally know well what my people are capable of. It’s not a joke when you think what my people have created. … They so wished and produced Christ and Christianity. So wished, and gave us Marx and socialism. Is it possible, therefore, that they will not present the world with their own painting? They will!”

Far from considering the culture of his youth “dying,” he indeed believed that the next step would be the creation of a particularly Jewish movement in painting. In 1935 Chagall elaborated further on developing all aspects of Jewish art: “We, Jews, do not have our own Baudelaire, Theophile Gautier, Apollinaire. We do not have the kind of a personality who with a powerful hand would forge the artistic taste and modern criteria. How can I help here?” All this strongly signals that Chagall wished to be not just a proud—and limited—Jewish pariah but, like Picasso, an almighty forger.

When, a year after the Revolution, Lunacharsky, now already the Bolshevik commissar, asked Chagall to open the People’s Art School in Vitebsk, the painter jumped at the opportunity, gratified that it was not just he but his native town, “forged” by him as the subject of his very Jewish art, that were so honored. “My eyes excitingly glistened,” he remembered in his 1923 autobiography. “I was all consumed by my new organizational activities. Around me were swarms of pupils, youngsters whom I intended to turn into geniuses in twenty-four hours.”

It did not end well, and Chagall left Russia for France again. By then, he was already the painter that we know now. That many considered Chagall’s beloved Yiddish culture to be “dying” only strengthened his zeal to keep it alive through his art. And that culture, indeed, still lives through him, just as he still lives through it.

Galya Diment is professor of Slavic languages and literatures at the University of Washington, Seattle.