Karl-Heinz Hoffmann’s Secret History Links Neo-Nazis With Palestinian Terror

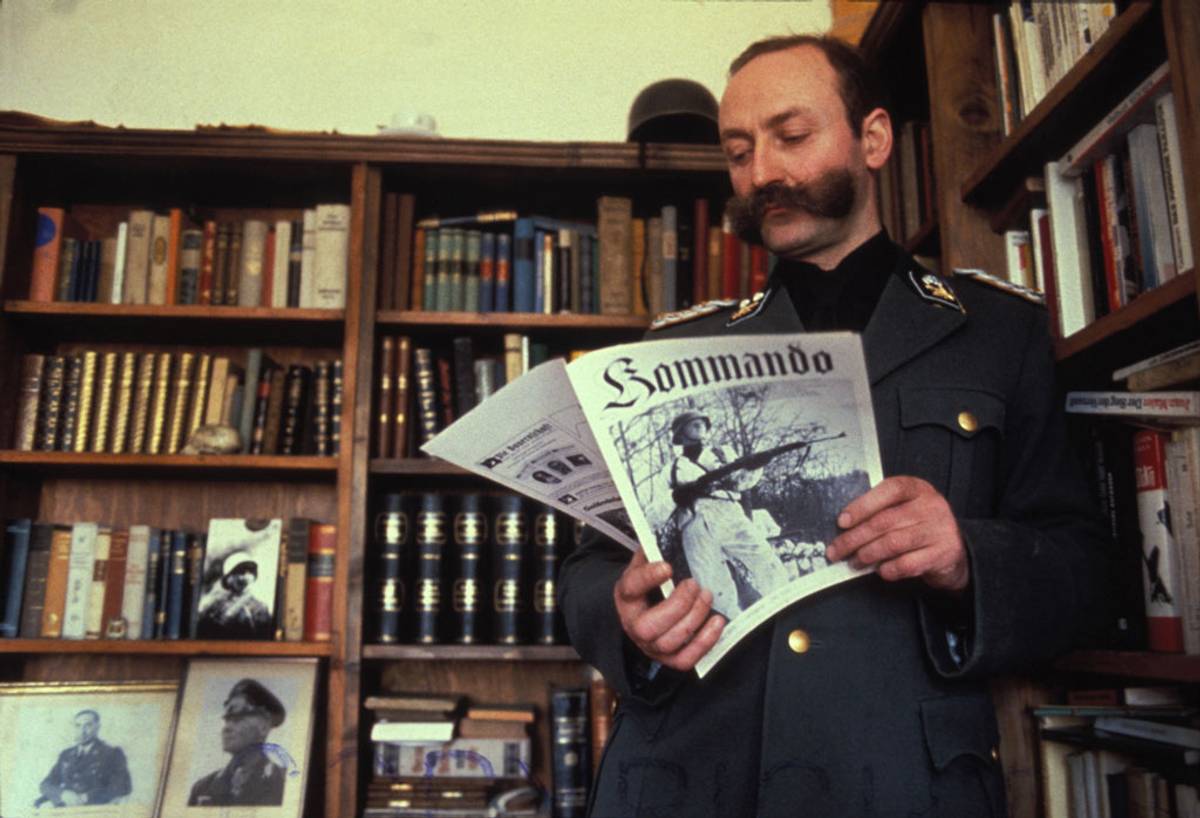

A neofascist lives on in his Bavarian castle

Last month, one of Germany’s most notorious neofascists, Karl-Heinz Hoffmann, made what he said would be his final public appearances, to discuss, “Judaism on German Soil Since Roman Times to the Enlightenment,” “The Anti-Jewish Jews” and/or “The Political Meaning of Islam.” Hoffmann is often portrayed in feature stories as something of a retired eccentric, residing with his wife, Franziska Birkmann, in Bavaria’s Ermreuth Castle, where he holds court and offers his perspective on a variety of issues, including social media, the abolition of churches and unions, and the “complete transformation of the economy.”

Rarely discussed outside German media is the neofascist group that Hoffman founded—the Wehrsportgruppe Hoffmann (Hoffmann Sports Group). While the group’s possible connection to the Oktoberfest bombing of 1980 is common knowledge in German political circles, recent publications rarely reference Hoffmann’s more notorious activities, including his alleged facilitation of a working relationship with a group of Palestinian terrorists in Lebanon—part of a network that terrorized Western Europe throughout the 1970s and ’80s. A review of Hoffmann’s activities and associates reveals a tangled web in which violent neo-Nazi organizations on the far right made common cause with Palestinian liberation groups who were heroes of the far left.

Little of what is known about Karl Heinz-Hoffmann’s early years suggested that he would become a leading neofascist. He was born in Nuremberg in 1937, but later relocated with his family when Allied bombing raids targeted his city. In his early adult years, he trained as a porcelain painter, and attended school to become a graphic artist. Later, in the 1950s, he became involved in the German art scene. He then traveled extensively, and took an interest in cultural studies of Eastern countries.

The first indication that Hoffmann held radical views occurred in the 1960s, when Hoffmann began speaking publicly about history and politics and reportedly expressed admiration for Adolf Hitler. Later, he was refused entry into Austria for advocating the reunification with Germany (which had last taken place during the notorious Anschluss in 1938) and for supporting the ideas of National Socialism.

In 1974, despite fairly strict laws that prohibit Germans from forming or joining the Nazi Party or openly promoting Nazi philosophy, Hoffmann founded the Hoffmann Sports Group, one of several, private, paramilitary organizations that sprouted up in Germany in the generation after WWII. Hoffmann’s group soon had some 400 or so members who became known for sporting Nazi-like uniforms and practicing paramilitary maneuvers deep in German forests.

In the latter part of the 1970s, German government officials began to consider Hoffmann a potential threat. Since 1978, Hoffmann had been training his neofascist organization at Ermreuth Castle, which had already seen service as a training school for the Nazi SS. A raid on his compound in January 1980 turned up guns, bayonets, gas masks, an anti-aircraft gun, a 12-ton armored car, and, in the basement, a puma. The discovery of this mixed arsenal led to an official ban on the Hoffmann Sports Group by the West German government.

Today, it is easy to wonder why a heavily armed neofascist organization was not taken more seriously; at the time, the West German government considered left-wing terrorism the greater threat. In the 1970s, hijackings, hostage-takings, and the storming of embassies by left-wing groups were routine, so Western European governments largely saw far-right groups such as Hoffmann Sports Group as oddballs or hooligans.

A series of devastating terrorist acts linked to right-wing organizations soon caused European governments to take right-wing extremism more seriously. In August of 1980, a bomb exploded at a railway station in Bologna, Italy, killing 85 people. It was believed at the time to be the worst act of violence in Europe since the end of WWII. Just weeks later, in September of 1980, a bomb exploded at the Oktoberfest beer festival in Munich, Germany, killing 13. The following month, in October, a synagogue was bombed in Paris, killing four. And on Dec. 19, 1980, Jewish German community leader Shlomo Levin and his friend Frieda Poeschke were gunned down in their home. In each case cited above, official investigations concluded that far-right individuals and/or organizations were responsible, although explanations for some of these attacks remain controversial.

As far-right terrorism exploded in intensity and frequency, intense scrutiny of Hoffmann Sports Group led the West German government to suspect that the organization may have been tied to one or more of the 1980 terrorist attacks. For example, the main suspect of the Oktoberfest bombing, Gundolf Koehler, had been a member of Hoffmann Sports Group. Koehler died in the explosion, and thus could not be questioned. Hoffmann and several members soon were arrested in connection with the bombing but were released for lack of evidence directly implicating them.

The double murder of Levin and Poeschke also raised suspicions. A pair of glasses belonging to Franziska Birkmann, Hoffmann’s then-girlfriend and owner of Ermreuth Castle, was found at the scene of the murder. Der Spiegel reported that a 1976 police raid on Hoffmann had discovered beretta submachine guns with soldered barrels, and a forensic analysis found that the gun used to murder Levin and Poeschke was a beretta whose barrel had once been altered.

According to data from the Global Terrorism Database, in 1973 there were 326 terror attacks total in France, United Kingdom, Spain, and Italy. In 1979, there were nearly three times as many. A RAND study concluded:

Although from 1973 onwards there were sporadic attacks on Jewish persons, synagogues or cultural centers … these were infrequent … But during the first ten months of 1980 alone, French police recorded 122 incidents of violence and arson perpetrated by neo-fascists and another 66 “serious threats and acts of vandalism.” A week before the Rue Copernic bombing, five Jewish institutions in Paris (including a synagogue) were sprayed with machine-gun fire by FANE/FNE (far-right) terrorists.

Noting the terror wave sweeping Western Europe, a journalist named Claire Sterling questioned the prevailing theories on terrorism and its causes. In her 1981 book, The Terror Network, Sterling asserted that fascist, leftist, nationalist, and religious terror groups were all connected through illicit networks, and that the Soviet Union and other key instigators were indirectly facilitating attacks against democracies by providing these groups with arms, money, and training. Sterling’s view of terrorism as a sort of worldwide crime network contradicted popular theories of terrorism as principled and organic resistance to oppression.

According to Sterling’s findings, terrorist groups that did not necessarily share ideologies nevertheless often worked together. Her logic, as presented, was that maintaining the arms, finances, and communications necessary to conducting terror attacks while thwarting law enforcement incentivizes militant groups to cooperate on some level. Furthermore, both far-right terror organizations, like Hoffmann Sports Group, and far-left groups shared a desire to weaken the hegemony of the United States and its allies. The far right’s aim was to rid their countries of what they saw as excessive and unwarranted foreign influence from both the Soviet Union and NATO; in some cases they mimicked the language of Third World liberation movements, whose aims and methods could seem inseparable from their own.

***

Shortly after Claire Sterling’s book was published, an event in Lebanon involving Hoffmann seemed to vindicate the journalist’s then-controversial theory of organizational links between far-right terror groups and liberation movements favored by the left. The Phalangists, a Lebanese Christian militia, presented four members of the Hoffmann Sports Group, and held a press conference, accusing the Palestinians of cooperating with neofascists. The Palestinians quickly countered by presenting in a press conference two Germans, Ulrich Bauer and Hans Eckner, who they claimed had defected from the Phalangists. However, Bauer and Eckner could not correctly describe the Phalangist symbol when challenged, and Eckner was identified as Uwe Berendt—the main suspect in the Levin double murder. Hoffmann had been suspected by West German intelligence of collaborating with Palestinian militants, but this incident was one of the most direct pieces of evidence to date that those accusations were true.

Hoffmann’s initial connection to the Palestinians was likely through Udo Albrecht. Albrecht was a German freelance criminal who fought with the Palestinians in the 1970 Black September uprising in Jordan against King Hussein, leading a militia of neofascists called the Freikorps Adolf Hitler. Sometime in the late 1970s, Albrecht introduced Hoffmann to Abu Ayad, a senior officer in the Palestinian Liberation Organization, and Hoffmann began to supply secondhand German vehicles, such as military trucks and Mercedes sedans to Palestinian militants in Lebanon. In the 1970s, Lebanon was a hub for international terrorist activity, hosting a diverse array of right- and left-wing groups from France, Germany, and Japan.

For a German neofascist leader like Hoffmann, cooperation with Palestinian militants was not an entirely foreign idea. The relationship between Hitler and Al-Husseini is well known, and there was further collaboration between the European far right and the Palestinians even after WWII. The Swiss financier Francois Genoud, who worked with the Nazis during WWII, was a major financial supporter of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), as well as a close friend of its founder, George Habbash, and of Black September founder Ali Hassan Salameh.

Near the end of his life, Genoud further confirmed suspicions of his involvement in terror activity, revealing to French journalist Pierre Péan that he had personally delivered the ransom letter to Lufthansa after Palestinian militants hijacked Lufthansa Flight 649, which had Joseph P. Kennedy II (former Massachusetts congressman and son of Robert F. Kennedy) on board. Lufthansa paid the $5 million ransom in full, without bargaining.

At times, German neofascists directly aided Palestinian terror attacks. For example, Der Spiegel revealed in 2012 that two German neofascists, Willi Pohl and Max Abramowski, aided Black September in the Munich massacre of 1972 by transporting the terrorists and helping them acquire passports. Like Hoffmann, Pohl’s initial connection to the Palestinians was through selling secondhand vehicles to them in Lebanon. In 1985, English skinhead Michael Davison and two PLO terrorists murdered three Israelis on a yacht near Larnaca, Cyprus.

In 1981, Hoffmann Sports Group began to unravel. Four members escaped a PLO camp and began cooperating with authorities against Hoffmann, complaining of hideous mistreatment, torture, and exploitation. Then in June 1981, Hoffmann was arrested in a Frankfurt airport, en route to Damascus, and put on trial for the murder of Shlomo Levin and Frieda Poeschke. The court ruled that it could not prove Hoffmann and Birkmann were involved, and Hoffmann accused his associate, Uwe Berendt, of committing the murder. Berendt had allegedly committed suicide in a PLO camp in Lebanon, and thus never stood trial. In June 1986, Hoffmann was sentenced to nine and a half years in prison relating to his neofascist activities and mistreatment of comrades in Lebanon. Birkmann received seven years in prison for her involvement.

Despite the Hoffmann Sports Group’s disintegration, other connected groups carried on its destructive legacy. A German neofascist named Odfried Hepp, a former member of the Sports Group, reportedly traveled to Lebanon to receive training in terrorist activities by PLO members. After the breakup of Hoffmann’s group in 1982, Hepp and a fellow neofascist, Walther Kexel, founded the Kexel-Hepp Group, and for a year, carried out deadly bombings against NATO military bases throughout Germany. After being arrested in 1983 and subsequently escaping, Hepp was rearrested in 1985 by French authorities while entering an apartment belonging to a member of the Palestine Liberation Front. Palestinian hijackers demanded Hepp’s release during the Achille Lauro cruise ship hijacking on Oct. 7, 1985—the same hijacking that led to the murder of Leon Klinghoffer, a disabled Jewish American and World War II veteran, whose limp body was hurled overboard along with his wheelchair.

By 1986, both Karl-Heinz Hoffmann and Odfried Hepp were in prison but not for long. In 1989, a German court ruled that Hoffmann had plausibly shown that he renounced his past and he was released. Four years later, Hepp completed his sentence and was released.

***

Since his release from prison, Hoffmann has publicly occupied himself in a number of activities, including real estate development and breeding the rare wooly Mangalica pig. He even set up a cultural foundation with the help of 130,000 euros from the Free State of Saxony at an estate called Kohren-Sahlis, which he put up for sale online in 2016 at an initial asking price of 666,666 euros.

Hoffmann continues to maintain his and his wife’s innocence in connection with both the Oktoberfest bombing and murder of Shlomo Levin. He expresses his ideas and muses on his past at public appearances throughout Germany, in regular blogs posted on a self-managed website, and on his YouTube channel, which he updates fairly regularly with help from his wife and cameraman, who shoots the videos in their Ermreuth Castle home where he trained his neofascist paramilitary group. One video even featured Odfried Hepp as a special guest.

One would hope that Hoffmann Sports Group and the neofascist terror network would be an artifact of the unique political situation of their time; however, connections between the European far right and Middle Eastern terror groups persist. In 2017, a delegation of the German far-right Der Dritte Weg party (The Third Way) met with Hezbollah in Lebanon.

The Jerusalem Post later revealed that Hezbollah and the Assad regime had a joint PayPal account with Der Dritte Weg party, linked to the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement. While PayPal shut down the account in January 2019, this did not end the relationship. In March of 2019, a delegation of European far-right politicians traveled to Beirut and met with Ammar Al-Moussawi, Hezbollah’s foreign affairs chief. Delegates stressed the need for stability to prevent an influx of refugees into Europe, echoing the desire for separation and isolation between Europe and the Middle East.

While it can be difficult to navigate the complex ideology and motives that cause far-right and neofascist Europeans to simultaneously despair of Middle Eastern immigration to Europe and cooperate with extremist groups from the Middle East, Karl-Heinz Hoffmann and his Sports Group show how interests between these two groups can converge in bloody ways. Both Hoffmann and Hepp’s groups and the Palestinian extremists they trained with sought to rid their countries of what they saw as excessive foreign influence. Using the language of liberation from foreign “occupation,” today’s alt-right, neofascists, and Middle Eastern extremists seek to rid their countries of what they see as a rootless global liberal hegemony while looking backward toward an idealized ancient past, which they hope to achieve through radicalization and terrorist violence.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Sam Izzo is a J.D. candidate at the USC Gould School of Law.