LARP-ing at the Crematorium (in a Suburban Hyatt Hotel)

A live-action role-playing game set up a scenario with ‘inmates’ and a ‘furnace.’ What could go wrong?

To be fair, the 40 people who signed up for a bit of costumed fun one July weekend in 2011 did receive advance warning. “This module involves flashing lights, dark spaces, mature themes, horrific visuals, contact boffer [foam] fighting, psychologically unsettling scenarios, and potential scenes of gratuitous violence,” read the introduction to the controversial live action role-play that game designer Michael Pucci had prepped for DexCon 14, at the Morristown, N.J, Hyatt and Conference Center. It continued in all caps: “PLEASE BE WARNED THAT THIS MODULE MAY NOT BE FOR THE SENSITIVE OF HEART, MIND, OR STOMACH. IF YOU ARE UNSURE IF YOU ARE ABLE TO DEAL WITH SUCH SCENARIO CONTENTS, DO NOT ATTEND.”

Shoshana Kessock, 31, was one of the players who had traveled to Morristown from Brooklyn, N.J, that Friday to attend the gaming convention and play Pucci’s shortened sample version of Dystopia Rising, the live action role-play franchise. The game is designed to provide a mixed bag of absurdities: Players, 16- and 17-year-olds with guardians present or adults, engage in improv theater (where they are audience and actors at once) and role-play combat, fleeing vicious human-hybrid monsters and otherwise conniving for their characters’ lives—all while fighting a deadly zombie infection somewhere in the 21st century, after world powers have inadvertently annihilated 95 percent of humankind. With nuclear bombs.

In the game, 14 “strains” of man evolve after “the fall,” including a strain of Pure Bloods who refuse to let go of their memory of pre-dystopian Earth. Others have chosen to follow religions, like the Telling Visions Church, whose adherents worship the mighty “Signal” that was once sent through little black boxes in living rooms, or King’s Court, a music-worshipping cult led by heavy-metal-style priests. To the live action role-play community, known to fans as LARP, Dystopia Rising is a global phenomenon and the peak of the art. LARPing offers adults a break from their mundane societal roles and an intensely intimate community of fellow gamers.

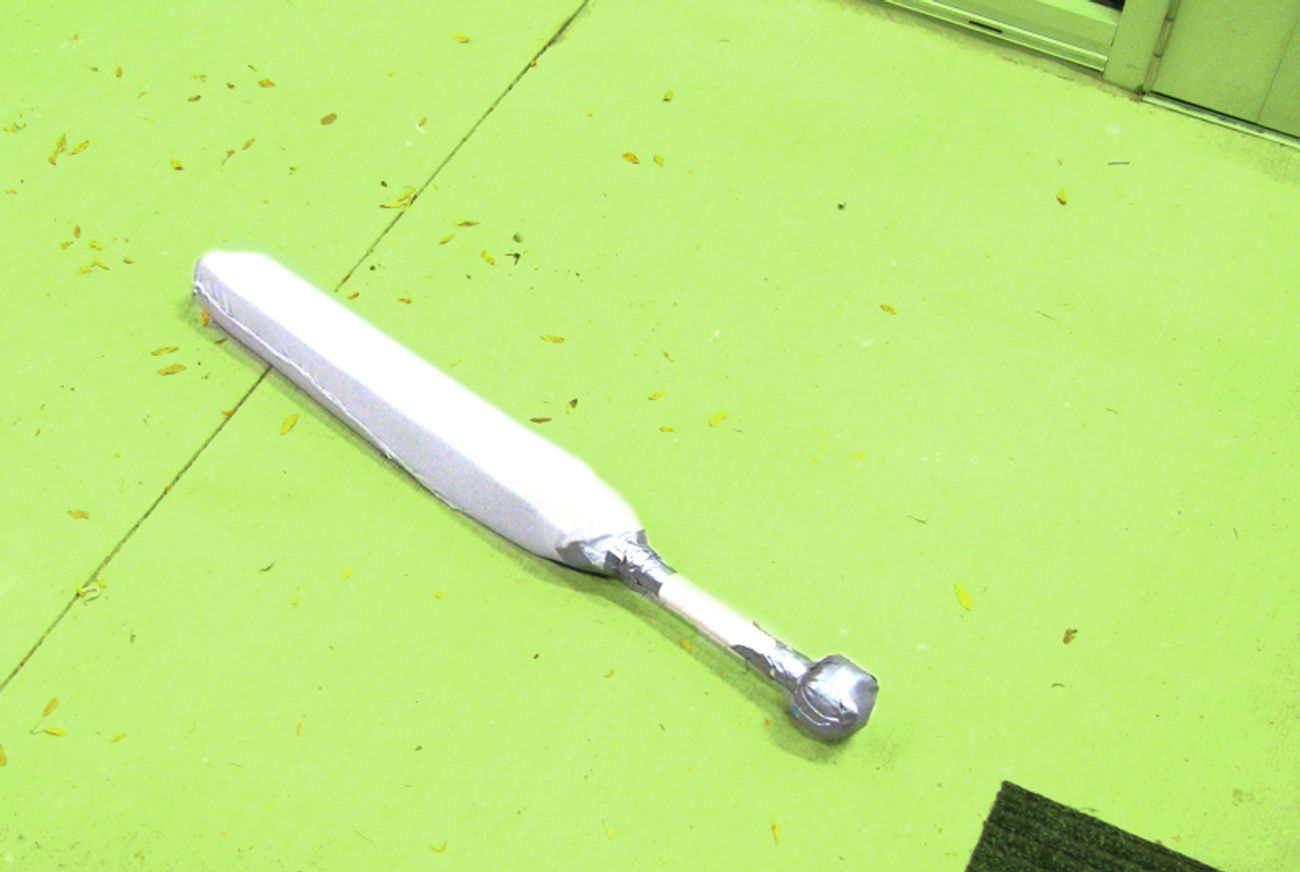

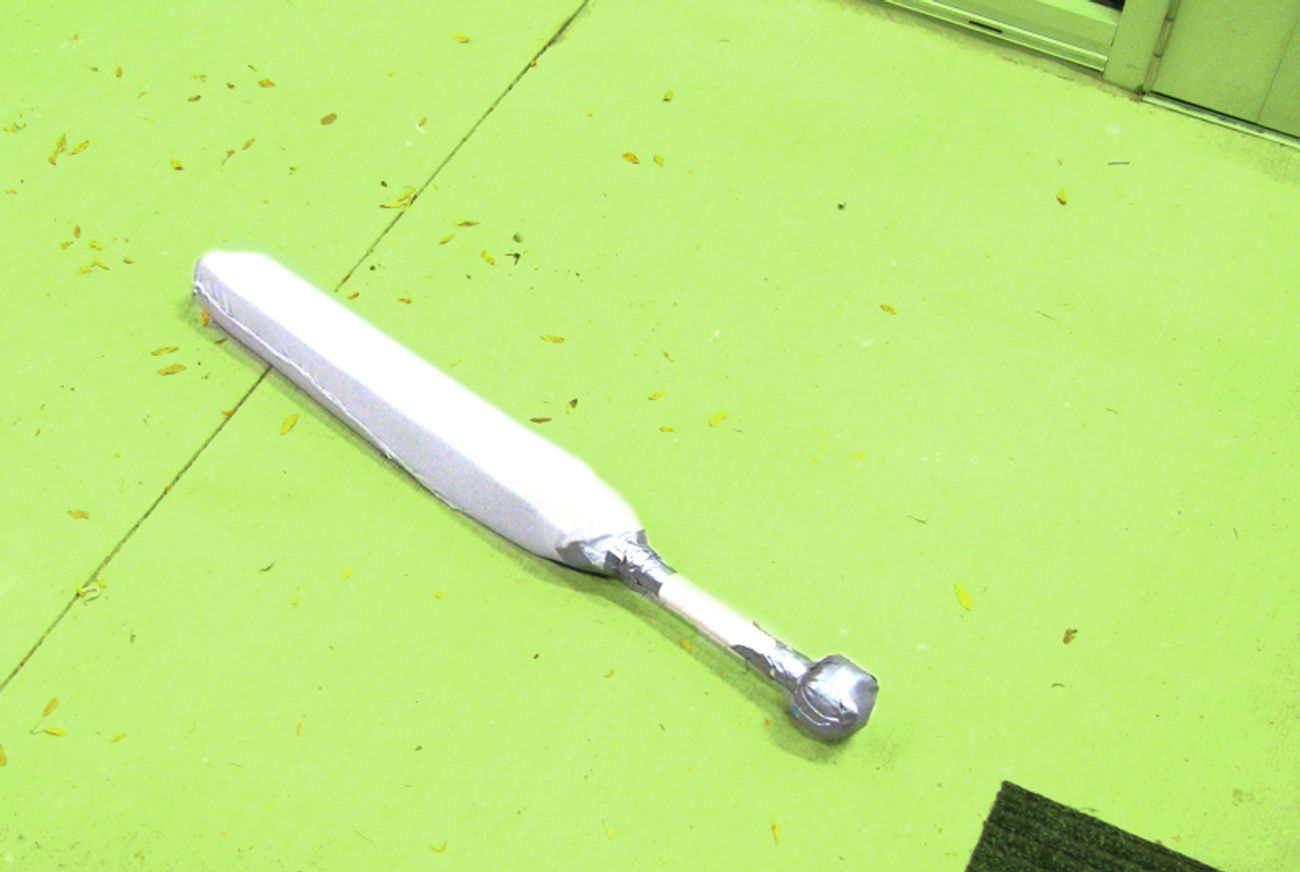

Kessock had been LARPing since 2005. Intimidated but also intrigued by the mature-audiences module of Dystopia Rising, which involves killing in-game “enemies” with Nerf guns and other foam and latex weapons and protecting oneself with Airsoft-style military vests, Kessock and a friend joined in. In real life, Kessock, tall and articulate, was adopted by a Jewish family—her mother was the daughter of Romanian and Hungarian Holocaust survivors—and raised Orthodox, a faith she left as a young adult. For this game, she named her Dystopia Rising character Elizabeth Hall and allied her with the Pure Bloods, a post-apocalyptic sheltered upper class. As a character, “Elizabeth,” who has the uncanny personality complex of sheepish innocence and mulish morals, dodges and—more often than not—pacifies her adversaries by keeping a remove until her principles push her to declare herself. She wears a signature vest dotted in music-band patches, namely those of Breaking Benjamin, Evanescence, and her favorite, Muse.

Before transitioning to live-action, Kessock had played “parlor” role-play, which normally lasts no longer than a few hours. Here she knew she would be tested in a new way—along with other players, warned explicitly by Pucci that the game would bring out dark moral quandaries. In her first game, Elizabeth was nearly killed by zombies and had to be resuscitated by a punk-rock priest. Unlike parlor games, “live combat” games such as Dystopia Rising have a plot that unfurls indefinitely—characters may last three months, or three years, but the world of Dystopia lives on. (Role plays with unlimited time-frames are known as “campaign games.”)

Outside of the convention, players pay $45 a weekend to attend monthly meet-ups at campsites in which scenarios, or “stories,” are outlined for them by the game designer. Players choose their own characters, jotting down their skills and backstory on character sheets submitted to the storytellers at the start and updated on an online database at the end. In so doing, they become the authors of their own avatars. Plots evolve, characters develop. If all goes well, players dress up, have fun, and their real-life counterparts unwind together with post-game drinks. Usually, though, what players say they remember most are the modules in which they made decisions they regret. Like forcing your in-game ally to step out of the way so you can shoot an innocent player with your pistol. Or purchasing and eating a helpless slave-boy because your character is a cannibal. Or throwing the last of a group of helpless inmates into a furnace. Decisions that make the Dystopia characters—and quite possibly the players behind them—cry.

***

Michael Pucci is a dark-haired, bearded 36-year-old and the CEO and co-founder of Eschaton Media Inc. When he is not gaming, producing game materials, writing handbooks, or running meet-ups—which is rarely—he enjoys coffee and Scotch. He describes his gaming style as “wide immersion,” which involves the creation of complex overarching worlds, all focused on entertainment. At age 22, after three years of dating, he had married an Orthodox Jew, although Pucci himself was not Jewish. During their two and a half years of marriage, he celebrated Jewish holidays and kept a kosher kitchen. His father-in-law taught him that their faith was more than the rote of ritual. For these experiences, he understood more than anything that “Nazi” was shorthand for “pure evil.” Eventually, he wanted to design games that challenge people’s moral notions and that demonstrate such things as the idea that the 20th-century atrocity that befell the victims of the Holocaust did not have to be reenacted.

That hot Saturday in July, Pucci and his dozen assistants—“storytellers” who know the scenario well, and marshals, who help with the mechanics of the world—simulated a Dystopian, post-apocalyptic industrial space out of the Morristown Hyatt ballroom. They flipped chairs, tossed tables, hung tarps, and dimmed the lights. They wrapped a punk-rock priest in fake barbed wire made of rubber to make him look like a captive. They set marks for hungry “gorehounds” to be acted out by some of the players. They molded tunnels out of black tarps hung on suspension frames to lead players to a “furnace” at the center of the abandoned factory. (A portable electric fireplace served here.) And then, like a stage director at a small-town traveling haunted house, he prepped the six people who volunteered to take on the role of something like concentration-camp inmates. And he warned players again to expect emotional content and to find a marshal if they became uncomfortable.

The captive forlorn souls were played by extras, “non-player characters,” or NPCs—disposable walk-ons who serve as antagonists to established main characters. They typically play enemies, and they have limited freedom to make their own decisions or control their own destinies. Before the game started, Pucci and his storytellers prepared their NPCs, instructing them that they had been tortured and wrangled into something like a concentration camp by “Final Knights,” a religion whose followers (including Zombies) believe that the post-apocalyptic earth was now a kind of Hell. Pucci asked the NPCs to show humility and elicit pity. If they were rescued, they were to act grateful—even if they knew that their rescue was temporary. The NPCs put on their most vulnerable puppy eyes, quivered visibly, and awaited the other players’ arrival with appropriate amounts of dread.

Pucci’s scenario went something like this: You are in an industrial space after the fall; zombies are everywhere; man-eating gorehounds, too. You are trapped inside; you must search for an exit. There are pitiful inmates, and tunnels, and a furnace. Now, play.

That night, Kessock joined two friends, Liam Neary, a slender 20-something with brown hair and a strawberry-red beard, and Clinton Rickards, 33, a lawyer from Connecticut. This was the third Dystopia Rising game that weekend: The first was designed to welcome new players, and the second was for moderately experienced players—an 18+ adventure. (Players came to call the module “Coney Island,” for its setting and scary carnival-like qualities.) Rickards, who had an affinity for playing NPCs at convention events (to vary his normal play in the role of a lacrosse-playing frat bro or, as his other stock character, a Disney-preaching priest), chose to play an NPC who had recently lost his entire family. Kessock, meanwhile, put on the guise of the big-hearted and clairvoyant teenage girl, Elizabeth, and Neary wielded his usual cowboy gun in the role he had been playing for two years, whom he had named “Tex.”

Before the module started, Pucci had told the assembled 25 players that once they entered the game, they could not leave the room in character unless they absolutely had to. “Go to the bathroom beforehand,” he said. “You will be in a virtual inferno for four hours.” (It ended up being more like five.) The group of 40 or so players included a burly character from “Old New York” named “Illest,” follower of the Wu-Tang Clan; a foul-mouthed character (she declined to give her name) whose role was a kind of bar wench who, like Tex, was “Merican”; and “Fallow Priest,” who was played by a Jewish man studying to become a rabbi.

As Kessock recounted to me after the game, for the first half hour inside, the players fought the man-eating beasts. Accordingly, Kessock, as Elizabeth, didn’t immediately notice the wailing inmates slumped in the shadows. But when she did, she was crippled by their torment: As a self-described “Psionic,” Elizabeth felt others’ pain. Meanwhile, the rest of the crew fought off the gorehounds and broke the code on the locked door to the tunnels that led to a blazing furnace. Players puzzled over a possible exit out of the factory rubble.

Pucci says his games are “sandbox” designs, in which worlds are created and then left to develop on their own. Where did the idea to throw people into the furnace come from? There’s disagreement. Pucci claims he never suggested anything. Kessock, though, says she saw Pucci giving hints from the margins: “How do we turn off the furnace?” Players tested the flame, waving their hands near it until Pucci exclaimed, “One fire!” which knocked everyone’s “health levels” down. Elizabeth tried to extinguish the fire with her recently learned pyro-kinesis skill—fighting fire with fire—but to no avail. Twenty minutes ticked away. Then, according to Kessock, Pucci finally graced Elizabeth, who was on her hands and knees at the end of the tunnel, with a Psionic vision by whispering in her ear. You see people throwing people in. She sat back on her heels. And you see the fire going out. (Pucci denies this version of events but acknowledges that the game can seem radically different to different players, depending on their experience.) Kessock, genuinely distraught, as she later explained to me, burst into tears. So did Elizabeth.

Oh God, please tell me that’s not the answer, Elizabeth thought, as she grabbed another player by the shirt. “We have to throw people in,” she cried. Elizabeth crawled back through the tunnel, burdened by her new knowledge. “The only way to get out,” she said to the other players, stopping just as she realized that she had already hinted at the answer. Arguments broke out over what to do next. Those among them without a steady moral compass would have the justification they needed to sacrifice the battered inmates they had set out to rescue.

***

When Clinton Rickards, one of Pucci’s friends and a longtime LARPer, suited up for Dystopia Rising’s premiere in Connecticut in 2010, only 30 or so people had showed for a game that would eventually grow to attract 300 people per event. Dystopia Rising drew so many players thanks to several major stylistic differences between Pucci’s role-play game and those played across the rest of America. Vampire: The Masquerade, which Pucci grew up playing, is the classic example of popular role-play in the United States: a parlor-style game that takes place inside one room and involves no fake weapons. Even though players could act out wars through playing cards, conflict resolution was often a drag. Players resorted to rock-paper-scissors or dice-rolling to determine whether or not an enemies’ blow had “hit” or “missed.”

Meanwhile, in Europe, some people were already making a living from LARPing and stretching its art in interesting directions. Claus Raastad, for example, fused parlor role-play with very serious topics, such as acting out couples’ therapy to pretend to grieve for a dead child. The genre spread through the region and became known as Nordic LARP. Gamers in Finland, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway were less focused on resolving combat-style engagements than interested in the emotional content of the modules. They experimented with so-called meta-techniques such as “bird-in-ear,” in which a non-participating player influences a character’s decisions by communicating their inner dialogue out loud, and “flash forward,” in which players can reveal a glimpse of the future in real time. Meta-techniques deliberately break the narrative frame in order to heighten tension and drama, transcending traditional storytelling chronology. Nordic LARP’s only missing puzzle piece seemed to be action; so Pucci weaved emotional intensity with another American genre gaining traction in the 1990s known as “boffer,” or live combat simulation using foam weapons. This paved the way for a new style of American role-play that was both action-packed and powerful.

Would an allegorical game based on the same moral dilemmas that faced people during the Holocaust be taking these ideas too far? Lizzie Stark, author of a 2012 book on LARPing, Leaving Mundania, has called the game an art form, much like theater: historical reenactment and intense improv acting that evokes emotion. She told me that Dystopia Rising compares to film fictions about Nazis. “Was that Quentin Tarantino movie about killing Hitler”—Inglourious Basterds—“something taken too far?” she asked. “What about Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade? Nazis are a sort of staple villain of our culture.” Stark also claimed that “playing mods around these topics can raise discussion around these issues by using a provocative premise.”

In the style Pucci helped develop, players participate in isolated modules that function as mini-games, chapters that layer to alter the overarching storyline over time. Within the span of a weekend-long event, the variety of these mini-games can be limitless. The moral dilemmas that players face, however, are the lifeblood of Pucci’s game design. “There is definitely a place for it.” Pucci told me, speaking about the tests his players encounter. “But I game for fun.” When you have power over someone else in a fantasy world engulfed in anarchy and that celebrates its anti-heroes, it seems easy to torture people, steal their clothes, or break their limbs—if those actions meant your own survival. Pucci said to me that his goal was to show that given widespread liberty to act barbarically, players might freely choose a more just path within the confines of the game—and should. The enjoyment of the game should not be based on the concept of what he called a “victory condition.” This is called “playing to lose.”

***

In the Morristown Hyatt, as players argued vehemently over whether they would incinerate the prisoners—they were just NPCs after all, who cared if they died?—Rickards, an NPC himself, trembled in the corner. Meanwhile, nearby, Elizabeth declared to Illest that she would do anything to survive. “But I will not do this,” she vowed. Illest agreed.

LARPers fiercely identify with their characters and feel acutely any existential threat. Players are determined to live. To do so in this game, they were realizing, they’d have to turn against the prisoners, even if they had just spent an hour defending them from gore-hounds and other menaces. Pucci had designed the module so that a certain number of people—it didn’t matter if they were NPCs or not—had to be sacrificed before the furnace would burn out, which would in turn allow the survivors to get out of the warehouse. By design, players were encouraged to sacrifice themselves: Dying in the furnace would only up their “infection rating” one level for the next game—most players had at least five levels before their character was irrevocably dead, which meant to participate in future games they’d have to create a new character or start over with their old character. But now half the players were busy corralling NPC prisoners against the wall to protect them, while the other half dragged the NPCs kicking and screaming into the flames. There was lots of yelling and discussion of what to do, but no one was volunteering to offer their own lives in sacrifice.

Rickards was huddled against the wall when he saw Tex, the friendly cowboy. In a creative gesture to enhance the gameplay, Rickards then decided that his NPC would mistake Tex for an imaginary brother-character named Levi. He reached his arms toward Tex, crying tragically for help. “Levi, you’re the only person who can save me,” he wailed as another player slid a sobbing girl across the room toward the furnace. Tex, the character played by Liam Neary, was caught off guard by Rickard’s feint and thought to correct him. In fact, he knew that Levi had died in the concentration camp a while ago along with the rest of his family. But Tex, the friendly cowboy, didn’t have the heart to tell him this, as Rickards played the part of the grieving brother with passion. “Levi, just hug me one last time,” he begged. So Tex did. And then two of Tex’s friends grabbed the inmate played by Rickards and dragged him into the furnace. All Tex could hear was, “I got to hug my brother Levi one last time.”

Pucci, on hand as a safety marshal, ensuring that the scenario was both physically and mentally safe for the players, stood to the side and watched. He was wearing street clothes to avoid being mistaken for a post-apocalyptic character. Many of the players were his personal friends, but their characters were behaving in ways that shocked him. Instead of making a personal sacrifice, they were making martyrs of the NPCs—the same NPCs who had been set up in the game to suffer as much cruelty as concentration-camp inmates. What was most disturbing, he said after the game, was how the same players who had spent two hours protecting NPCs from man-eating beasts and comforting them as they shook from abuse, eventually broke and turned on them. “It was very difficult for me to look at these people who I respected, all making similar decisions,” Pucci said. “It was frightening.” Neary, the young bearded player who had thrown Rickards’ character into the furnace, told me he still has nightmares from the module. “I visibly changed how I was acting,” he said, adding that the most obtrusive emotions he experienced were frustration and helplessness.

***

Before long, the furnace had been fed. The NPCs had been consumed by the fire. All of the known prisoners had been sacrificed, and yet the furnace still roared. It needed one more body.

Elizabeth backed into a corner. There, hiding behind a couch, was a balled-up prisoner, cowering in fear. She looked up at Elizabeth just as the bar wench came around the corner. The bar wench, cursing in a thick southern accent, pulled a Nerf gun out of her corset.

Tex came over. The Priest of the King’s Court whom they had unraveled from the barbed wire followed him. When the two men realized who Elizabeth and the bar wench were hiding, they immediately moved to take the prisoner. Elizabeth raised her gun to the Priest’s forehead.

“If you try,” she said, “I will cut you down.”

“Do it,” he replied. Her finger trembled against the plastic trigger. “Cut me down,” he said in a stern voice, “because I’m going to have to take her.” Tex had a “skill” he could deploy, one that defined him as strong and tough enough to intimidate other characters. When he played this skill, called fear, the confronting character must run away.

“Elizabeth, darlin’,” Tex said. “I’m sorry.” She watched as her friend, whom she had thought contained a heart of gold, mouth “I’m sorry” before playing fear. Tears fell from the corners of her eyes as she turned and ran. With Elizabeth out of the way, Tex and the Priest easily maneuvered around the bar wench, picking up the shrouded inmate and, ready to wipe their hands clean of the slaughter, tossed her into the furnace so that the team could move forward.

With the door leading out of the section of the warehouse now open, the remaining group of 24 crawled through to the exit, unsure of what they would find on the other side. They were met by a cackling circle of 10 or so violent zombies, adherents of the religion of Final Knights—played by another group of NPCs—who had hoped that the altar and mass sacrifice would serve as a tribute to coax a devil-figure back from the dead to rule a crazed Earth. (“One of the key portions of the module design,” Pucci later wrote in an email, “is that there were no direct correlations between real world antagonists and the fictional ones in the module.”)

“You think you’re pure?” Elizabeth screamed. “How dare you! I will get you! I will show you what a Pure Blood is.” The bar wench and Tex pointed their guns. Illest flexed his biceps at the reeling maniacs, and “Medic” pounded his fist into his palm. And so, as a unified team, unlike before, they killed.

“And then we walked out like everything was fine,” Kessock told me later in her Brooklyn office, remembering the events of that weekend. “Well, nothing was fine. People will still say the words Coney Island in character, and we go numb.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Olivia Simone is a writer living in New York.

Olivia Simone is a writer living in New York.