Laugh Riot

The sharply funny, darkly political comics of Sergio Langer

At the height of the 2006 Lebanon war between Israel and Hezbollah, the Argentine humor magazine Barcelona published a one-frame cartoon depicting two bearded, hook-nosed, tzitzit- and yarmulke-wearing men whose Haifa apartment has just been hit by a rocket. “Fuck, do something!” one of them says. “Those sons of bitches have launched a Katyusha and destroyed my toilet and my jacuzzi!” “Well then,” says the other, “we’ll bomb Gaza, Beirut, the airports, the refineries, the highways, and we’ll destroy the Parliament.”

The cartoon quickly aroused the ire of many in Argentina’s Jewish community. “Del arte de cruzar los oceános,” a blog by an Argentine Jew living in Israel, denounced the work as anti-Semitic for its stereotypical caricatures, its stance against Israel’s actions in the war, and its ignorance of the realities of Israeli life (a jacuzzi, the blogger pointed out, would be a rare luxury in that middle-class desert nation). Comunidades, a newspaper circulated in Buenos Aires’ Jewish community, echoed the denunciations almost to the letter. Some members of the community took their outrage a step further, sending emails and letters to the artist comparing his work to 1930s Nazi propaganda.

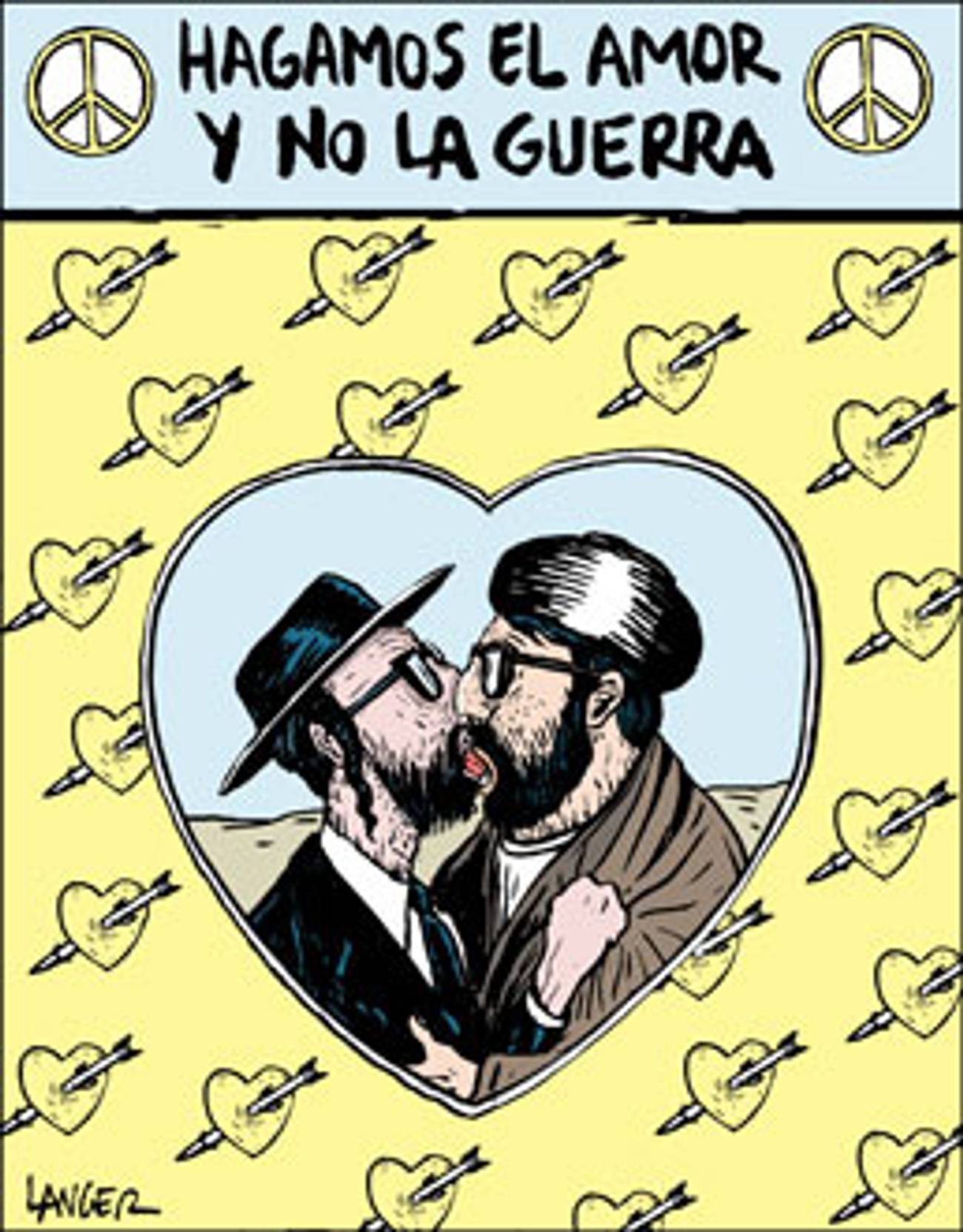

The target of this outcry was the celebrated Argentine cartoonist Sergio Langer, a man deeply invested in his Jewish heritage and also deeply committed to using humor, in his words, “to make things right, to fix injustice…to mock Nazis.” “If I perceive [authoritarianism] and I draw it and do it humorously, that’s mission accomplished for me,” Langer says. His work forces the viewer into close contact with a host of the hideous: rotting military dictators, dominatrix suicide bombers, lecherous priests, and Klansmen, to name a few. A history of violence shadows these crude, emphatic drawings, which attempt to call out reactionaries at the same time as they offer a time-honored form of Jewish cartharsis: laughing at tragedy, laughing at suffering, and laughing at ourselves. Clearly influenced by the grotesque physicality of Robert Crumb and the irreverent irony of Art Spiegelman, Langer has crafted an original style that can be both vulgar—impossibly ugly priests in the throes of orgasmic ecstasy—and tender—scenes depicting mothers and sons.

Over the course of his 30-year career, Langer’s work has appeared frequently in the major Argentine newspapers Página/12 and Clarín, in the Peruvian magazine Somos, and in U.S. publications such as Newsweek, the Miami Herald, and the now-defunct New York Newsday. Despite this steady work, Langer was known almost exclusively to the cartoon cognoscenti until five years ago, when his comic strip “La Nelly” brought him widespread recognition for the first time. Published daily on the back page of Clarin since September 2003, “La Nelly” chronicles the misadventures of a bigoted middle-aged woman whom Langer sees as an exemplar of the Argentine middle class. Even in the most mainstream venue in the Argentine cartoon world, Langer’s work snaps with an outsider’s bite.

Langer, who is 49, relishes throwing viewers into a world that brazenly mixes senseless violence with dark humor. His work often elicits profound discomfort, challenging artistic boundaries and social acceptability. Langer’s stated goal is to fight authoritarianism, and he sees skewering political correctness as part of the battle. Usually cast as opposites—a Holocaust-denying reactionary like Iran’s Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, after all, spews defiantly un-P.C. statements—political correctness and authoritarianism do have in common a desire to suppress or limit speech. “There’s a paranoia, a madness,” Langer says, “because society is very intolerant, and it [pretends] not to support its own intolerance.”

Langer’s own dark personal history colors the violent images and provocative voice of his cartoons. Born in 1959 in Once, Buenos Aires’ traditionally Jewish neighborhood, Langer grew up hearing first-hand stories of Nazi Europe from his maternal uncle, who escaped Romania and fought in the Soviet Army at Stalingrad, and his survivor mother, who was imprisoned for four years at the Mogilev-Podolski concentration camp. Growing up in Buenos Aires in the aftermath of Eichmann’s dramatic capture, Langer eagerly collected newspaper clippings that detailed the prosecution of Nazi war criminals. He dedicated his first cartoon collection, Langer: Blanco y Negro, to his “beloved superhero Simon Wiesenthal” (who responded with a gracious letter saying that he was “touched,” and noting of Langer’s black humor that “sometimes the desire to chuckle gets stuck in the throat”).

As a child, Langer made sense of the horrors of his family history through play. A typical scene in the Langer house involved the young Sergio tracing soldiers and tanks in flour on the kitchen table as his mother cooked at the stove, a habit that he translated to pen and paper as an adult. “It’s like I still haven’t finished exorcising that,” he says. “In fact, I can say that I’m a pacifist, but I love weapons. I love to draw them; I love to watch war movies. When I was a kid, I played Warsaw Ghetto and killed Nazis…you can say that’s a kind of Jewish humor.”

When Langer was 12, reality caught up with the darkness of his fantasies. His father, who fled to Argentina from Poland in the 1930s, was murdered during a robbery of his business in the Patagonian city of Rio Gallegos. Five years later, in 1976, a military junta seized power in Argentina, launching a clandestine war on leftists, intellectuals, young people, Jews, and many others unlucky enough to arouse the government’s paranoid suspicions. While studying architecture at the University of Buenos Aires during this period, Langer began to draw for Humor, a subversive magazine that published covers mocking the dictatorship. Though many critics of the junta faced murderous reprisal, the military granted Humor an unspoken amnesty, permitting the underground magazine to mock the government as a sham demonstration of democracy and free speech. “In 1979, I published one of my first drawings,” Langer remembers. “[It was] of a military officer saying, ‘We’re not going to stay in power,’ while he had a chain tying him to the presidential seat. I would do that kind of thing with the military, but they never gave me any problems. That said, I knew what was going on—not in detail, but I knew.”

While the dictatorship is a recurring theme in his work, Langer comes to terms with the horrors of the past most fully in his comics about the Holocaust. In the 10-page comic story La Vida Es Bella (Life Is Beautiful)—published in its entirety in the July 2008 issue of the Argentine comic magazine Fierro—Langer places the viewer inside the mind of his childhood self, defending the right of each generation to engage with remembrance in its own way. The story begins with the young artist drawing furiously at the kitchen table as his mother cooks on the stove. Against this quotidian backdrop, the young Langer peppers his mother with a series of questions about the Holocaust that quickly exasperate her. “If you could change destiny what would you do: Save the six million who the Nazis killed or the family that you’ve made in Argentina?” he asks. “Enough!” she shouts, sending the young Langer back to the table to resume drawing.

In the upper frame of each of the comic’s remaining nine pages, the young Langer imagines a series of events that he thinks might have stopped or impeded the Holocaust: a group of 250,000 Jews leads a violent resistance on Kristallnacht; German industrialists threaten to rescind their support of Hitler if he continues to use Jewish slave labor; the Pope leads a group of 300 bishops to Dachau to intercede on behalf of “our Jewish brothers”; Hitler succeeds as an artist, becoming one of the most controversial German painters of the 1920s and ’30s. On the bottom of each page, a train carrying Langer’s mother and grandmother chugs through a starless night until, in the final frame, we see a guard tower and a smokestack looming in the distance—reality dashes the young Langer’s hopeful fantasies.

La Vida Es Bella personalizes remembrance in a way that passive reverence could not. “There’s a kind of official culture of what memory is and how we must remember,” Langer says. “But everyone sees things in his or her own way. It’s not The Diary of Anne Frank and nothing else.” Langer argues that irony and humor can help us better come to terms with historical truth than can “official culture,” which makes the work of remembrance into a compulsory ritual—a phrase like “never again” can be uttered very solemnly without any genuine individual reflection on its meaning. Langer’s speculative, ironic work argues that each generation needs to hone its own voice for that memory to stay relevant.

But how does this care for memory, history, and justice fit in with Langer’s pugnacious, highly controversial Lebanon War cartoon? Is it possible to reconcile the harshly criticized polemicist with the zany memorialist of La Vida Es Bella?

Langer admits that his mistake in the Lebanon war cartoon was in using stereotypical Jewish caricatures as stock representations of Israelis, enabling his critics to interpret it as a blanket statement that Jews are petty and barbarous. By employing these simplistic caricatures, he gave his critics an opportunity to interpret his work as sinister. His real target, he says, was the kind of conservative thinking that he saw expressed in Israel’s actions in Lebanon. “There’s a sector of the Jewish community that says, ‘If it’s good for the Jews, then it’s good—that’s it, nothing else matters,’” he says. “It’s like if there’s a war between Iran and Iraq, saying ‘That’s great! Let them kill each other!’ That kind of thinking has always existed for better or worse, but it doesn’t interest me at all.” Had the cartoon more clearly conformed to the sentiment of that statement, it would likely still have been criticized; but without stock Jewish caricatures, it may not have been so easy for some to label it anti-Semitic.

While acknowledging this, Langer says he has no regrets. In a world where so many are quick to take offense, his comics try to shake us out of a nervous silence that not only suppresses speech, but also suppresses laughter. This false tolerance—cohabitation enabled by averted eyes and guarded speech—mutes the possibility of a more vibrant world of acceptance. Langer belongs to a long tradition of proudly subversive cartoonists who believe that creating challenging art means recognizing that some people will be offended by it. “I understand that it’s a delicate subject,” Langer says about the Lebanon War, “but sometimes it’s worth it to go over the line, to take a risk.”