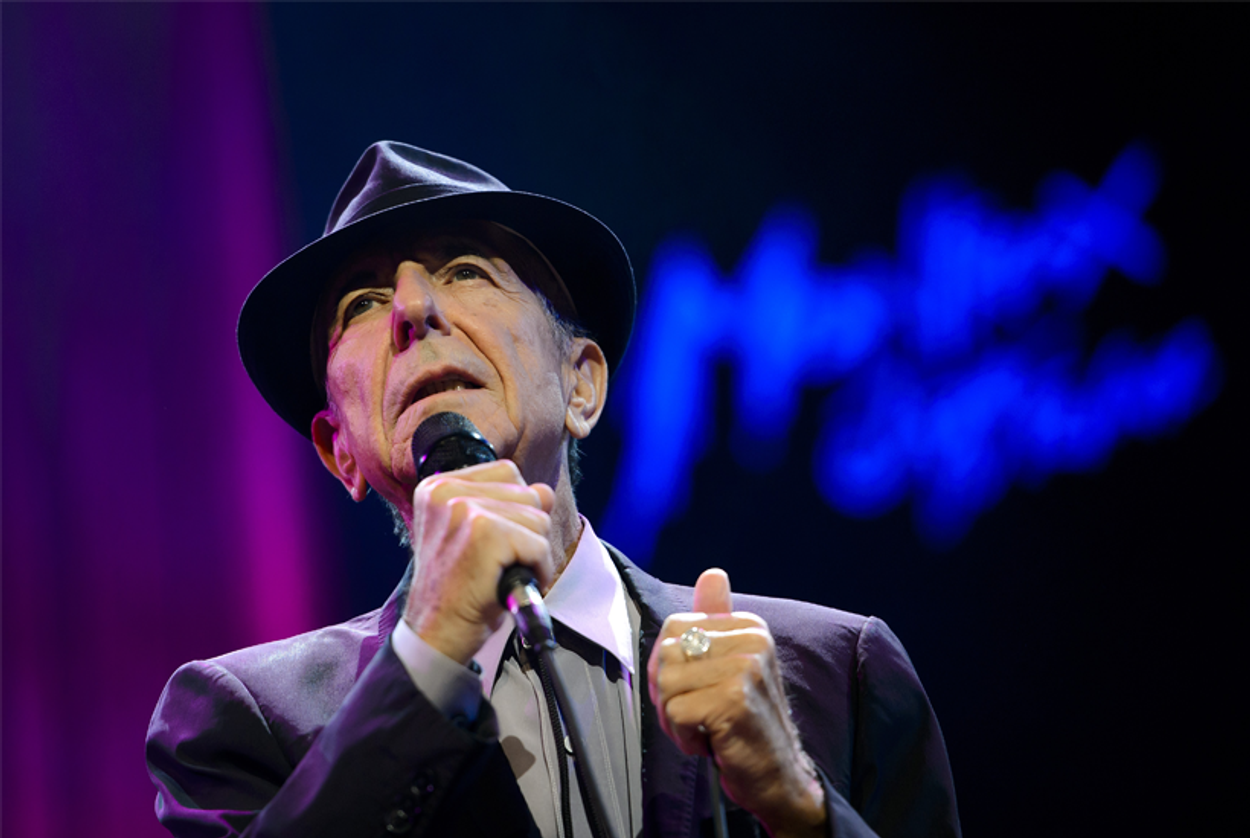

Is Leonard Cohen’s New Album His Best Yet?

The singer has had better songs, but his new record captures his ideas more clearly than ever

Imagine, for just one perfect moment, that you are Leonard Cohen. After an inconvenient brush with financial ruin, you are required to emerge from a decades-long retreat—some of it spent in the austere auspices of the Mount Baldy Zen Center outside of Los Angeles—and go on tour. You retake the stage reluctantly but soon seem to discover within yourself a facility for performance that has eluded you for four decades. Maybe it’s because you’ve finally come to terms with the act of standing before hordes of strangers each night and sharing intimate poems meant for individual women with names like Suzanne or Marianne. Now your voice is deeper and your spirit calmer, having finally completed, as you had so eloquently put it, your manual for living with defeat. It’s a line from a song, of course, and it’s a very fine one. You include it on your 2012 release, Old Ideas, your first album in nearly a decade. It climbs nimbly up the American charts and stops at No. 3, an overwhelming 60 spots above your career’s best-performing record to date, which was released in 1969. In other words, you’re almost 80, and you are more celebrated and comfortable, perhaps, than you’ve ever been in your life. Here’s the question: What now?

It’s a metaphysical problem, really, or even nearly a Zen koan: The stories that we tell ourselves are always about becoming, never about being. We follow our heroes as they struggle and as they suffer and as they triumph, but once they’ve slipped into a life of small joys, we close the book on them. Even our most introspective artists do the same: Burden them with success, and it’s almost guaranteed that their next project will feel strangely hollow. How much rage, after all, could a content and well-compensated Eminem really produce? How many of Kurt Cobain’s existential anxieties could survive his elevation to the rock pantheon? If you’re Leonard Cohen, then, chances are that you, too, are at risk of ending your period of grace with an album that fizzles when it ought to shine.

Take it as just another sign of Cohen’s singularity, then, that his new album, which will be released next week, shows absolutely no sign of the aforementioned symptoms. Because the usual platitudes—a masterpiece! his best yet!—slip right off of an artist who had spent half a century deftly resisting other people’s attempts at definitions, think of the new album, Popular Problems, as dawn on Mount Baldy, inviting you into a sparsely decorated landscape that nonetheless gives you all the discipline and all the space you need to contemplate the questions that are truly worth considering.

Here he is, for example, in “Almost Like the Blues,” reciting over a piano track that manages to be at once sober and seductive: “So I let my heart get frozen /To keep away the rot /My father said I’m chosen /My mother said I’m not /I listened to their story /Of the Gypsies and the Jews /It was good, it wasn’t boring /It was almost like the blues.”

It is, first and foremost, a funny line: Is Cohen chosen? Depends on which of his parents you ask. But if it’s a joke, it’s a cosmic one: The very nature of chosenness, the spiritual engine of Judaism for millennia now, is that our seminal moment at the foothills of the mountain came with no instructions. Who’s chosen? For what? For how long? Can we be unchosen? Are our children chosen by default? God never says, leaving us to wonder for eternity what it means to have been chosen. In the meantime, all we can do is guess and make up stories—and songs—that are good, that aren’t boring, and that come as close as is possible to the pure emotional convictions of something like the blues, as transcendental an art form as we’ve got.

This sort of songwriting is harder to pull off than you’d think. Any other artist looking at the mirror and seeing himself at the peak of his success might have been tempted to become, as one Israeli rock journalist put it, the Shimon Peres of rock ’n’ roll, dispensing platitudes and enjoying the comfort of his laurels. But Cohen is remarkably unsentimental. Lighter on his feet now than he’s ever been, he delivers his line with humor and with charm, but he’s still as committed as ever to the role that has made him mean so much to so many of us, namely that of the chronicler of the secret particles of truth and beauty most of us are too dense to absorb.

“I cried for you this morning /And I’ll cry for you again,” he tells us in another new song. “But I’m not in charge of sorrow /So please don’t ask me when /I know the burden’s heavy /As you bear it through the night /Some people say it’s empty /But that doesn’t mean it’s light.” It’s the same profound observation he has delivered in earlier songs—“Anthem,” especially, comes to mind, with its lines about there being a crack in everything, which is how the light gets in—but here it’s leaner and more energetic. The world, Cohen reminds us, is fundamentally torn, and it’s easy to lose faith in the possibility of redemption, or, just as terrible, to demand constant and joyless vigilance. Instead, Cohen’s songs are here to show us how to live in a state of disgrace while keeping our hopes high and a half-smile on our face. We still have problems, but it’s the job of prophets like Cohen to learn how to make them popular.

And a prophet he is, a thoroughly Jewish one. He’s here to tell us that salvation is possible, that it’s our job, that it’s not all that it’s cracked up to be, and yet that it still beats the alternative. “I’m lacing up my shoes /But I don’t want to run,” he sings in “Slow,” the album’s first song. “I’ll get there when I do /Don’t need no starting gun /It’s not because I’m old /And it’s not what dying does /I always liked it slow /Slow is in my blood.” He could be talking about love-making or about the end of days, but it would hardly matter. His point is the same—there is no transformative moment, no rapture, nothing but the deep, deep joy that comes only with learning how to live life as it actually is, a very broken hallelujah. This is not to negate the possibility of God; it’s just to define our relationship with him in more realistic terms, which, in the long run, is better for both parties. And it’s not to deny attempts at greatness: As this magnificent new album is here to remind us, as Cohen himself is living proof, as only a people who’d wandered in the desert for 40 years and who’ve waited for millennia to return to their homeland can know, great things come to those who wait. Slow is in our blood.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.