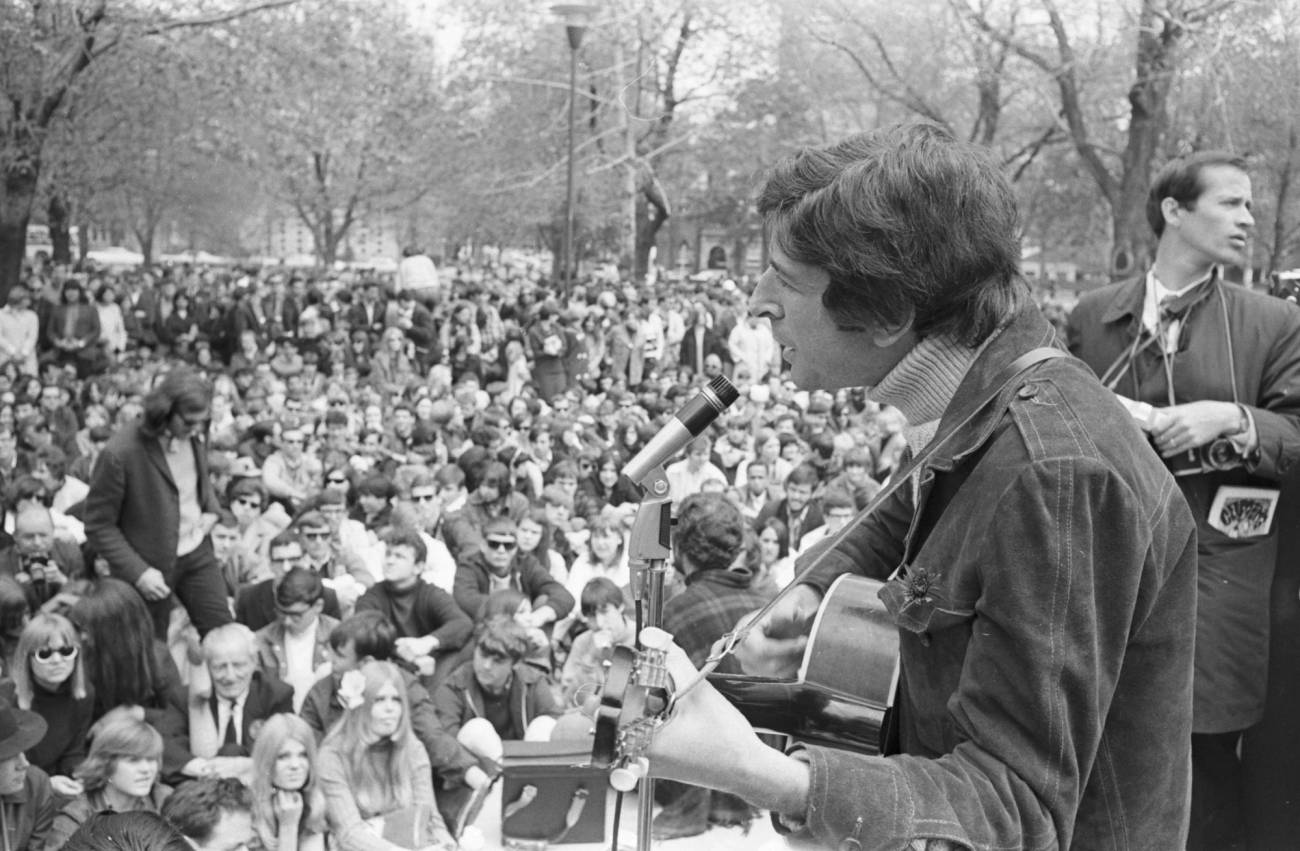

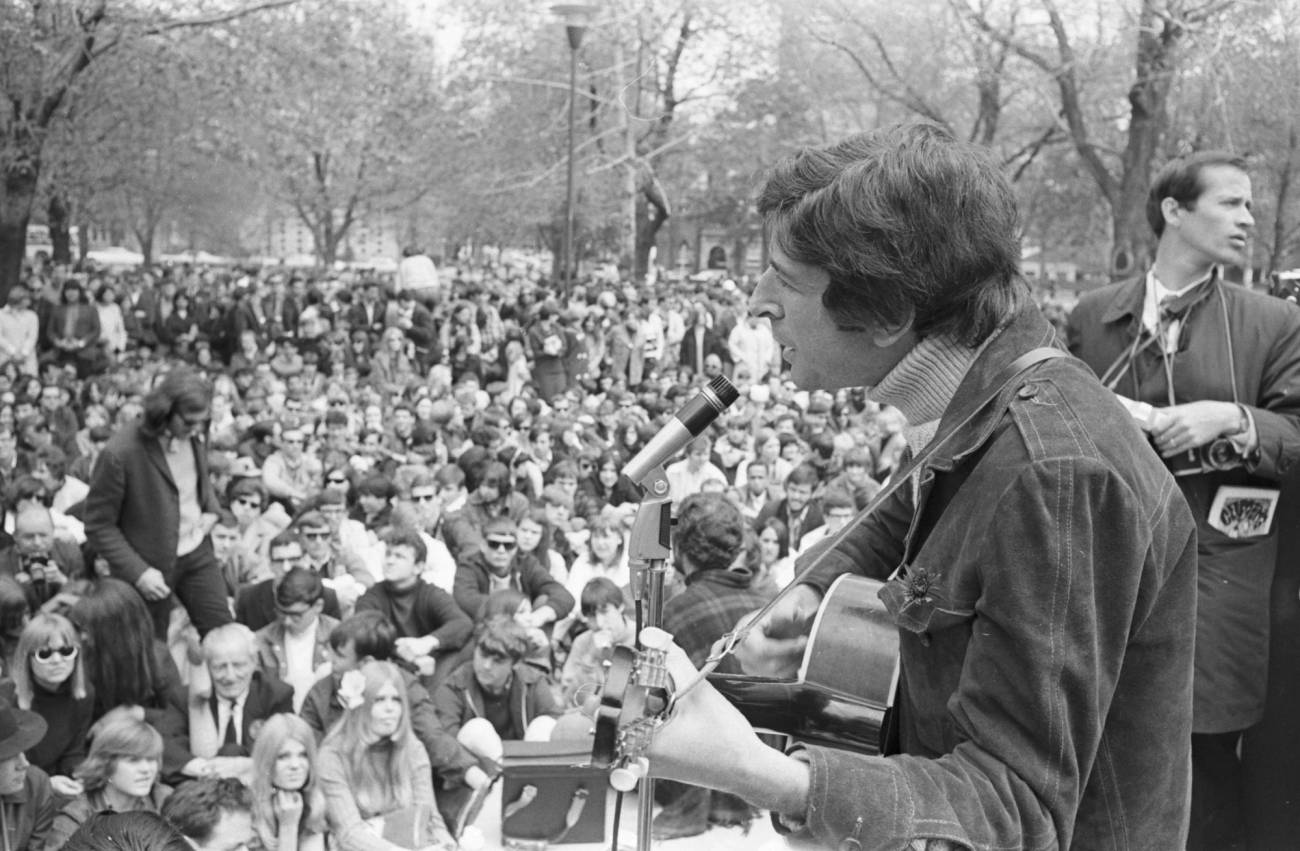

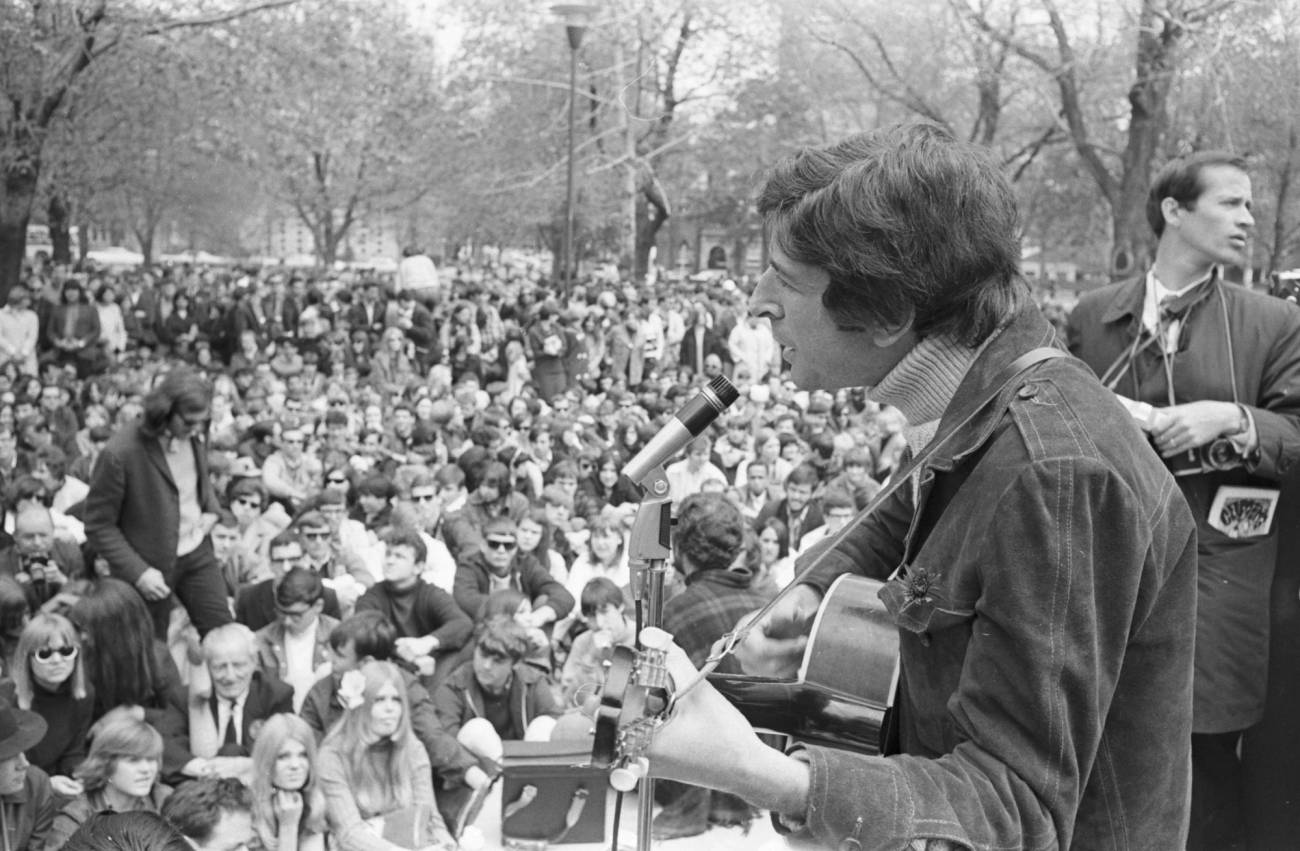

Leonard Cohen at Queen’s Park

Music made Cohen rich and famous, but it deprived us of the brilliance of his poetry

On May 22, 1967, I attended a “love-in” at Toronto’s Queen’s Park. Advertisements for the event hinted at psychedelic drugs, tantric sex, and spiritual rejuvenation through meditation. On the musical bill was the now-forgotten rock group The Rabble, the little-known Isabella Blues Band, folk artist Buffy Sainte-Marie, as well as the poet, novelist, and newly fashioned singer/songwriter Leonard Cohen.

Earlier that year I’d been introduced to Cohen’s poetry by my grade 11 English teacher. Young and savvy, Ms. T. reasoned that if she was to convert her class—composed mostly of Jewish students—to poetry, it would be best to sidestep our stodgy poetry text and hand out mimeographed copies of works by three of Canada’s prominent Jewish poets: A.M. Klein, Irving Layton, and Leonard Cohen. It was an inspired mix: Klein’s nostalgic “Heirloom” was heart-rending, Layton’s “The Convertible” raunchy, and Cohen’s “Song” whimsical and endearing.

I almost went to bed

without remembering

the four white violets

I put in the button-hole

of your green sweater

and how I kissed you then

and you kissed me

shy as though I’d

never been your lover

While all three poems spoke to me, I felt closest to Cohen’s. I was what Cohen called “an inner-directed teen,” and found the poem’s longing to recapture innocence irresistible. From our neighborhood library I checked out his second collection, The Spice Box of Earth, and was struck by the perfectly pitched lyricism, the imaginative leaps, the wry, self-deprecating voice that for decades would speak to me and others of my generation. I soon read through the poetry of Klein and Layton, too, and while I marveled at their work, (Klein’s “Portrait of the Poet as Landscape” is one of the great poems of the 20th century) I identified most strongly with Cohen’s persona. I went to Queen’s Park that May day to get a glimpse of a poet I revered.

According to the journal I kept at the time, it was an unusually cool day for late May: 46 degrees Fahrenheit. Buffy Sainte-Marie wore a sweater. An experienced performer with two well-known hits, she drew an enthusiastic reaction from the crowd of 4,000—a mix of hippies, activists, students and professors—with her engagingly tremolo voice and stage acrobatics. Cohen, too, was dressed for the weather in a thick turtleneck and suede jacket. He began his brief performance by saying “Spring called me here.” Then he sang two songs—“Suzanne,” and “So Long, Marianne”—followed by a recitation of two of his poems: One was “Travel”:

Loving you, flesh to flesh, I often thought

Of travelling penniless to some mud throne …

The crowd’s response was muted. Most people do not know how to react to spoken poetry. More to the point, Cohen’s musical performance was disappointing. He played without any backup musicians and while his guitar work was adequate his singing was not. He’d given his first public performance a few months earlier in NYC, the widely known event where Judy Collins pushed him on to the stage, encouraging him to perform. Shortly after, in a letter to his girlfriend, Marianne Ihlen, concerning that first performance (the Toronto engagement was his second), Cohen observed that his guitar “had gone completely out of tune,” and that his voice “was unbelievably flat.” At the Toronto concert his guitar was in tune, but the voice was again thin and off key.

While Cohen had failed to win the hearts of the audience, the songs, I thought, were exceptional. Some months before, I’d heard him sing “Suzanne” and “The Stranger Song” on the CBC and was impressed. A guitar player myself, I had figured out the chords to “Suzanne” and would play it at weekend parties. The song, I noticed, had a mesmerizing effect on listeners. They’d stare into space and dream.

At that point I thought of Cohen’s music as nothing more than an intriguing diversion from his literary pursuits. Years later I discovered that, initially, he thought the same. In a 2006 interview with Shelagh Rogers of the CBC, Cohen explained, “I thought of myself as a writer, but I couldn’t make a living that way.” He went on to say that, inspired by artists like Dylan and Phil Ochs, he began writing songs “as an interim activity, just to tide myself over.” Those who heard the songs, including star-maker John Hammond, knew their worth. Three days before Toronto, on May 19, Cohen had gone into NYC’s Columbia Studio E in the CBS Radio building on East 52nd Street to begin recording his first album, Songs of Leonard Cohen. Released later that year, it garnered much praise. After that, there would be no more novels and the quality of the poetry would decline as songwriting became Cohen’s métier.

Cohen’s success as a popular songwriter has its roots in his early poetry. More than other poets of his generation, he was tuned into contemporary culture and had a gift for coming up with the timely image, the memorable turn of phrase. By his third book he was writing credible poems concerning the Cuban revolution, Joseph Goebbels, opium, and junkies. He called his ability to cull from the contemporary scene “scavenging.” It culminated in the funny, profound, and moving novel Beautiful Losers, which Cohen described as “this odd collection of jazz riffs, pop-art jokes, religious kitsch, and muffled prayer.”

From his earliest books, his metrical proficiency was notable. One can draw a line from several of the early poems to the music he later produced. Here is the six-lined, “For Anne”:

With Annie gone,

Whose eyes to compare

With the morning sun?

Not that I did compare,

But I do compare

Now that she’s gone.

“Go by Brooks” is the enactment of an erotic encounter that begins with staring, moves to stimulation, and culminates in an oceanic outpouring.

Go by brooks

Where fish stare

Go by brooks

I will pass there.

Go by rivers

Where eels throng

Rivers, love,

I won’t be long.

Go by oceans,

Where whales sail

Oceans, love,

I will not fail.

In that same 2006 interview with the CBC, Cohen explains his motive for adhering to traditional structure at a time in modern poetry when most practitioners were leaving it behind:

I don’t trust my own spontaneous nature to come up with anything interesting, and form imposes a certain opportunity to get deeper than your first thought … When you submit yourself to form, then something happens and you’re invited to dig deeper into the language and to discard the slogans by which you live, the easy alibis of language and opinion.

W.H. Auden espoused the same. In his collection titled Shorts, he wrote:

Blessed be all metrical rules that forbid automatic responses,

force us to have second thoughts, free from the fetters of Self.

It wasn’t only money that attracted Cohen to lyrics. In an age that saw the Beats, the Projectivists, and the Post Modernists take over the poetry field, song writing allowed Cohen to pursue his love of rhyme and meter. As his voice deepened and darkened with experience, the early metrical verses proved to be a training ground for the brilliance of “a long-stem rose,” “without your clothes,” and “Everybody knows.” But not all the early poems are formally structured; in fact, the strongest (“Last Dance at the Four Penny,” “To a Teacher,” “What I’m Doing Here”) are examples of what can be accomplished with free verse and it is these sorts of poems that would, sadly, no longer be forthcoming.

Did Cohen think he’d given anything up by moving into the arena of song? Did he even make a distinction between the composing of songs and poems?

Over the years, he spoke in interviews about poetry and song writing. At times he presents song writing as “poetry by other means.” Other times, he distinguishes between the two, stating, “Poetry is a private experience, songs are public.” In poetry, he explains, one can shift modes of time, one can linger. Not so with song writing. “A song,” he tells us, “is a fast-moving train.” Ultimately, he believed the two were separate genres which is why he continued to publish books of poems alongside the albums.

When Dylan received the Nobel Prize for literature, some claimed it as a victory for those who see no difference between a practitioner of the literary arts and a serious composer of songs. Certainly, Cohen’s testimony of the many verses written and discarded for each of his lyrics, speaks to the long and intense labor involved in their creation. Still, there are obvious differences between a poem and a song. In a poem, words are surrounded and strengthened by silence. In a song, words are bolstered by melody and harmony, which is why the poet Robert Lowell discounted Bob Dylan as a poet, claiming “he relied on the crutch of his guitar.” Most song lyrics, when divorced from their music and read on the page, come off as surprisingly thin. There may be exceptions, and some would say that the lyrics of Cohen, Dylan, and Paul Simon can stand on their own. But why should they? Isn’t song writing the art of marrying musical phrases and words, and isn’t that as complex a process as the one involved in writing a long poem or a short story?

There is another question we can ask: Does the experience of reading a poem differ substantially from that of listening to a song? Baudelaire thought the intent of poetry was to provide a frisson, a shudder. Is the frisson experienced in hearing Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” or Dylan’s “Man in the Long Black Coat,” any different from that had by reading a poem by Margaret Atwood or W.S. Merwin? A shudder, after all, is a shudder. Yet there are perceived differences. When Cohen talked about shifting modes of time in a poem, he was thinking of its hold on our attention, its way of prompting us to go back and reread it as it unfolds. The reading of a poem is demanding in a way that listening to a song is not. And it is that difficulty that makes poetry more of a counterculture event than even the most avant-garde song, especially given our increasingly limited attention spans.

Cohen said he liked the idea that people would listen to his songs while doing the dishes, a thought that repulsed Auden who gloried in poetry’s demands. As he so eloquently put it:

After all, it’s rather a privilege

amid the affluent traffic

to serve this unpopular art which cannot be turned into

background noise for study

or hung as a status trophy by rising executives,

cannot be “done” like Venice

or abridged like Tolstoy, but stubbornly still insists upon

being read or ignored

What happens when “this unpopular art” is practised by a celebrity? The first book of poetry that Cohen published after he became an international star was The Energy of Slaves. It was a greatly anticipated event in Canada, and the shock of it generated debates on CBC radio and in newspapers at a time when—imagine this—literature could shock:

the 15-year-old girls

I wanted when I was 15

I have them now

it is very pleasant

it is never too late

I advise you all

to become rich and famous

or

The amazing vulgarity

of your style

invites men to think

of torturing you to death

Several of Cohen’s fellow poets and critics were kind and came to the conclusion that he was writing anti-poetry, but it was not the anti-poetry of the great Eastern European poets (Miroslav Holub, Vasco Popa, Zbigniew Herbert) who used their unadorned style to goad poetry into a deeper humanity. Cohen’s is a book of resentments. Each fragment (most read like embryonic notes for poems) is headed by the tiny icon of a razor blade. The speaker is disillusioned, bitter, and seemingly angry at poetry itself for abandoning him.

I have no talent left

I can’t write a poem anymore

You can call me Len or Lennie now

The poems don’t love us anymore

they don’t want to love us

they don’t want to be poems

I’d be remiss if I didn’t cite the one fine poem in the book, written in traditional form and psychologically insightful regarding the shifting power dynamics of a relationship:

You tore your shirt

to show me where

you had been hurt

I had to stare

I put my hand

on what I saw

I drew it back

It was a claw

Your skin is cured

You sew your shirt

You throw me food

and change my dirt.

From this point forward, Cohen’s poetic adventure would rest on our interest in his narcissism. Here on in, he would play the ingenious game of, on the one hand, inviting the reader’s envy, while on the other indulging in what the critic Eli Mandel called “masochistic revelation and sexual self-pity.” It says much about our culture that so many found this attractive.

Cohen’s game is continued in his next book, Death of a Lady’s Man, which employs journal entries, drafts of poems, and commentary. Some of it is brilliant: the mordant humor of “The Unclean Start,” the imaginative weaving of “The Radio,” the lyric power of “The Rose.” Like all of Cohen’s projects, Death of a Lady’s Man is extremely ambitious, yet it ultimately fails because it substitutes an ironic voice for the structural concerns that are poetry.

Close to the book’s end there is once again an admission:

Lost my voice in New York City

never heard it again after sixty-seven

That is, after Cohen recorded his first album.

There are those who contend that Cohen’s poetic career was resuscitated by his next collection, Book of Mercy, a suite of 50 prose psalms. Professor Brian Trehearne calls it “the greatest of his [Cohen’s] works, as essential to my experience of twentieth-century literature as Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets.” High praise. But I have always considered it Cohen’s weakest work. Adopting the cadences of the Jewish prayer book, the speaker professes spiritual struggle. The poems, however, fail to convincingly enact this, and the language comes across as turgid. Yet in the same year that Book of Mercy appeared (1984), Cohen released Various Positions, an album that includes some of his most cherished songs: “Hallelujah,” “Coming Back to You,” “and “Dance Me to the End of Love.” Is the Muse that presides over Song different than She who presides over Poetry?

Cohen’s ongoing assessment of his own poetic achievement is in keeping with the self-conscious attitude of modern artists. It also provides us with clues to his thinking about poetry. In Book of Longing, for instance, there is the five-part poem “All My News,” that concludes,

Undeciphered

let my song

rewire circuits

wired wrong

and with my jingle

in your brain

allow the Bridge

to arch again.

Cohen believed that his art healed, not through intellect (“Undeciphered’) but through emotional rewiring. It is true that we appreciate a poem through its imagery and sound before we are able to decipher it. But the word “jingle” is telling. The OED defines it as “a short slogan, verse, or tune, designed to be easily remembered, especially as used in advertising.” There is an advertising quality to pop music with its hooks, riffs, and earworms. It consolidates us as a community in that we share its effect, while poetry foregrounds our individuality by speaking to our inner selves.

Perhaps Cohen’s most insightful assessment appears in his posthumously published collection The Flame. The poem “No Time to Change” ends:

How dare I care

What’s on my plate

O gentle book

You’re much too late

You missed the point

Of poetry

It’s all about them

Not about me

Did Cohen feel that his later work was not enough—to use Martin Buber’s phrase—I and Thou; was it too much I and I? Poetry, by its very nature, is autobiographical, if not in content then in the poet’s singular use of language. But it is not self-obsessed. It’s a concern with self vis-a-vis the world. At its best, it can help us broaden our imaginative selves and sympathies.

While listening the other day to Cohen’s album Dear Heather, I was reminded in a concrete way of what was gained and lost when Cohen took to songs. The album is his least typical, least commercially successful—and his most interesting. A song like “On that Day,” concerning 9/11, with its simplicity, humility, and brevity, reaches beyond jingle with its questioning lines: “Did you go crazy or did you report / On that day they wounded New York?” The double sense of “report” as in reporting for duty, but also providing a report, i.e., witnessing, cuts to the heart of the matter. There is little doubt that Cohen’s literary sensibility added a degree of gravitas to the culture of popular song, that he significantly raised its bar.

At its heart, Dear Heather is a return to Cohen’s Montreal roots. On the pamphlet accompanying the CD are his playful line drawings of fellow poets Irving Layton and A.M. Klein. On some tracks, Cohen, backed by jazz musicians, recites poetry as he did in Montreal night clubs back in the ’50s. He recites the powerful lines “From bitter searching of the heart / We rise to play a greater part,” from “Villanelle for Our Time” by the Canadian poet F.R. Scott, Cohen’s professor at McGill University. He recites his early published poem, “To a Teacher,” his lament for A.M. Klein, who midway through his career, suffered a complete mental breakdown and was hospitalized, after which he no longer wrote or spoke:

And now the silent loony-bin

where the shadows live in the rafters

like day-weary bats,

until the turning mind, a radar signal,

lures them to exaggerate mountain-size

on the white stone wall

your tiny limp.

Here is the Leonard Cohen who went missing when the albums began to appear. In the stanza above, the music is embedded in the words. And the words, released from the tyranny of rhyme and set rhythm, go naked in their effect, free of jingle and slogan. Authentically, they reach out to touch the pain of a fellow poet, and by extension, all who suffer.

Kenneth Sherman is a poet and essayist. His most recent book is the memoir Wait Time.