The Lace and the Grace

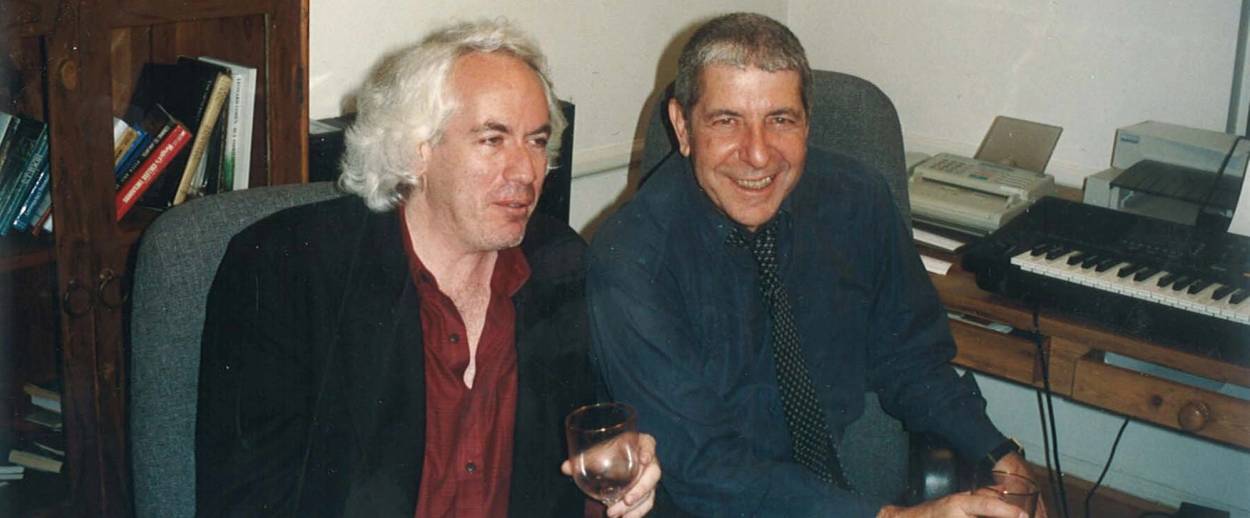

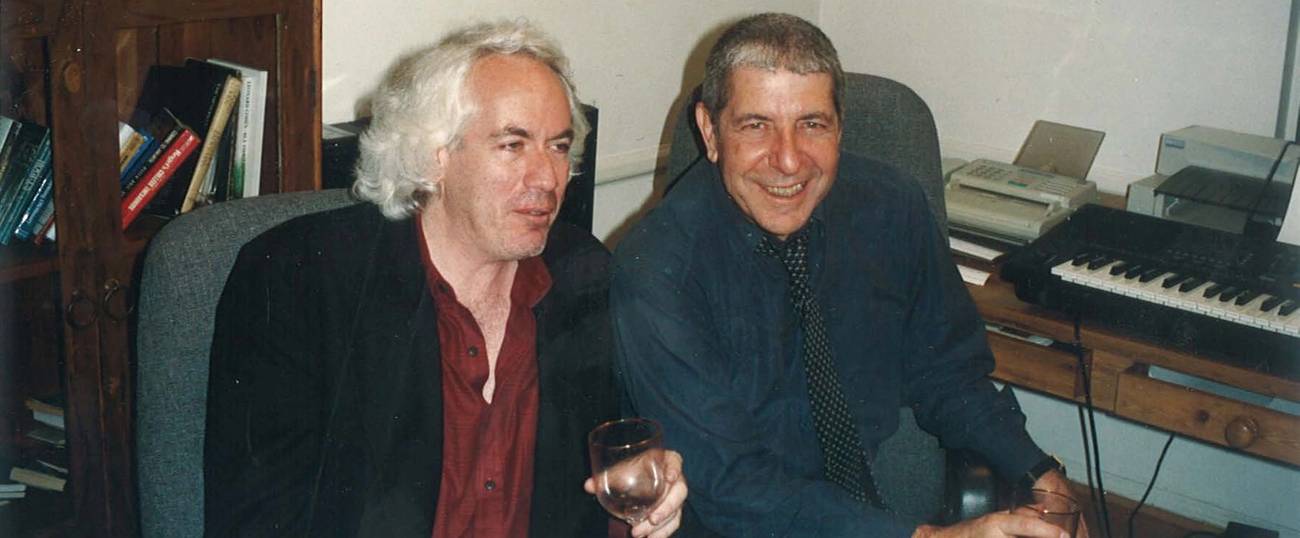

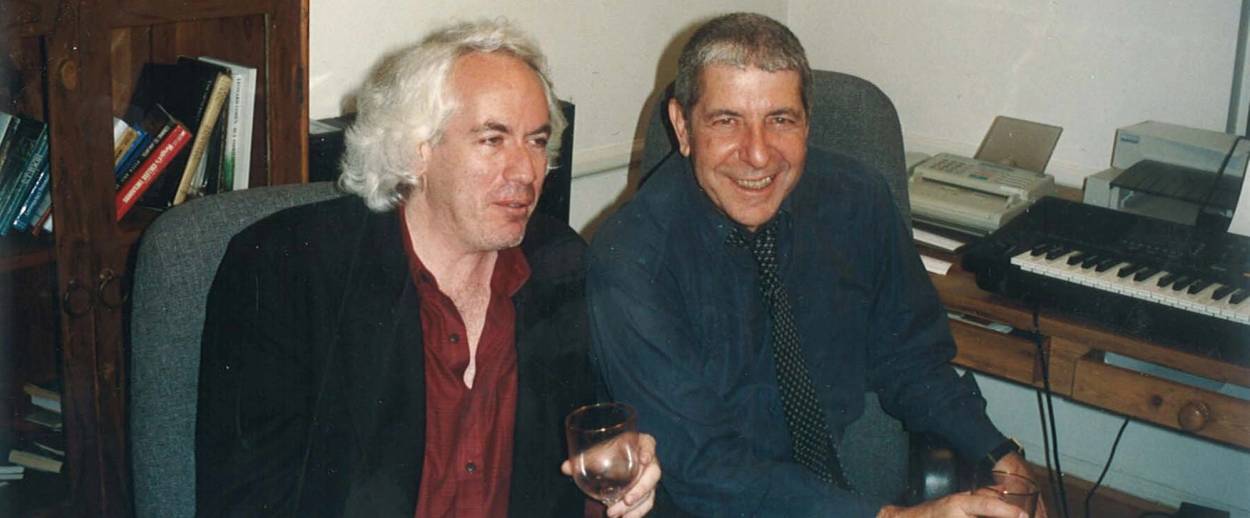

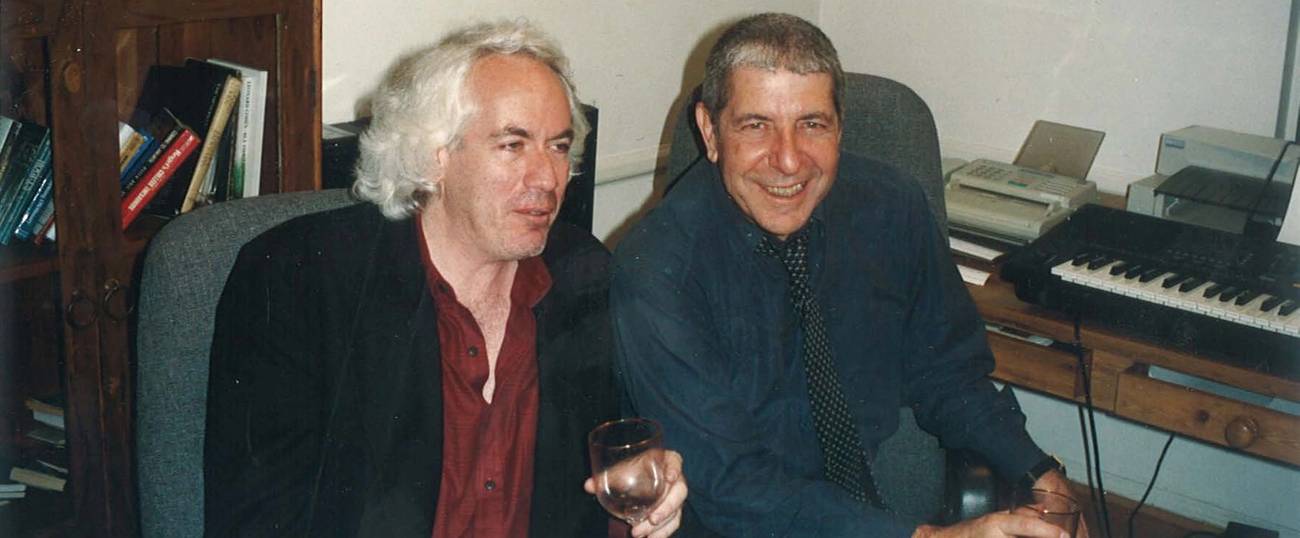

Remembering Leonard Cohen

Remarks written for Leonard Cohen’s memorial service at Ohr HaTorah Synagogue in Mar Vista, California on Dec. 11, 2016.

In a fragment of a journal that he kept on the island of Hydra in 1983, Leonard amusingly recalled a kind of philosophical disputation that resulted from his attempt to write what he called “a metaphysical song.” Wryly mocking his own spiritual ambition, he writes that the song “attempted to exaggerate the maturity of my own religious experience and invalidate everyone else’s.” It was to be called “Letter to the Christians.” Leonard was never more Jewish than in his lifelong engagement with the figure of Jesus: has there ever been a more Jewish, or more damning, or more compassionate, characterization of Jesus than “almost human,” which is what Leonard called him in “Suzanne”?

After a few days Leonard had four stanzas for his new song, and judging by the lines that he reproduces in his journal he was right not to proceed with this one. The subject of the verses was God and the Galilee and the Crucifixion. Leonard sang the lyrics to a friend as they waded in the Aegean, and a few minutes later his friend composed a wicked reply. It went like this: “I really hope you stumble on/ The Great Red Whore of Babylon/ Forget the Grace/ Enjoy the Lace/ Have some fun and carry on.” It appears that Leonard appreciated his friend’s retort. He notes immediately that “the beach was full of beautiful young women whom I desired uniformly at a very low intensity.” He spots a lovely “new-born Christian” sitting on a rock and “hurries off” to charm her with some smooth talk about Grace. After the Grace, I presume, came the Lace.

In the weeks since Leonard’s death, he has been portrayed as a sage, a rebbe, a kabbalist, an exegete, a kind of troubadour theologian. There is some truth to these descriptions: he was devoted to the cosmological speculations of his own tradition and others, he had an erotic relationship with big ideas, and in his way he never quit the theistic universe. But as I mourn him I want to remember him accurately, and so I want to insist that Leonard was not so much a wise man as a man in search of wisdom. He found it, he lost it, he found it again, he tested it, he lost it, he found it again. The seeking was his calling. He was never certain, never done, never daunted, never saved.

And so, against those other descriptions of him, I wish to recall that my brother was also, and more primarily, a poet, a lover, a voluptuary, a worshipper of beauty, a man who lived as much for women as for God, a man who lived for women because he lived for God, a man who lived for God because he lived for women, a servant of the senses, a student of pleasure and pain, an explorer whose only avenue of access to the invisible was the visible, a sinner and a singer about sin, a body and a soul preternaturally aware of the explosive implications of the duality.

Leonard was a good man with desires, and he had the courage of his desires. The man who seeks forgiveness even as he seeks experience: he is the hero, or the anti-hero, of all of Leonard’s work. The power of Leonard’s graciousness was owed to the history of his turbulence. His songs are the songs of a wounded and wounding man. I have almost never known a humbler person—what other star of popular music filled stadiums to sing on bended knee?—but it was the humility of one who was also impertinent and defiant. His was the modesty that succeeds temerity.

Leonard cherished the rules because he recognized his inclination to break them. He was bored by innocence, by the calm before the storm, by stormlessness. But the calm after the storm—that was his ideal. His poise was his triumph, his method of self-mastery, the profoundly moving evidence of his sovereignty over his rioting appetites. But the appetites accounted for as much of Leonard’s flavor as the poise.

And now it’s come to distances and only we can try. I wish to testify that my own existence has been permanently and irreversibly desolated by Leonard’s departure from the world. There were inflections of my soul for which he was my only comrade, states of fragility and perplexity for which he furnished my only solidarity. He taught me a great deal about the conditions of gratitude and gladness. Most of all, he taught me that it is by our longings that we are most truly known. And now I will long for him, and for his genius for longing.

If, as Leonard wrote in Book of Mercy, “holy is that which is unredeemed,” then an aspect of holiness attached to my ravishing friend, and will forever attach to his memory. Te’hay nishmato tse’rurah be’tsror ha’chaim. May his soul be bound up in the bundle of life.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Leon Wieseltier is the Isaiah Berlin Senior Fellow in Culture and Policy at the Brookings Institution and the author of Kaddish.