Literary Phenom Flames Out

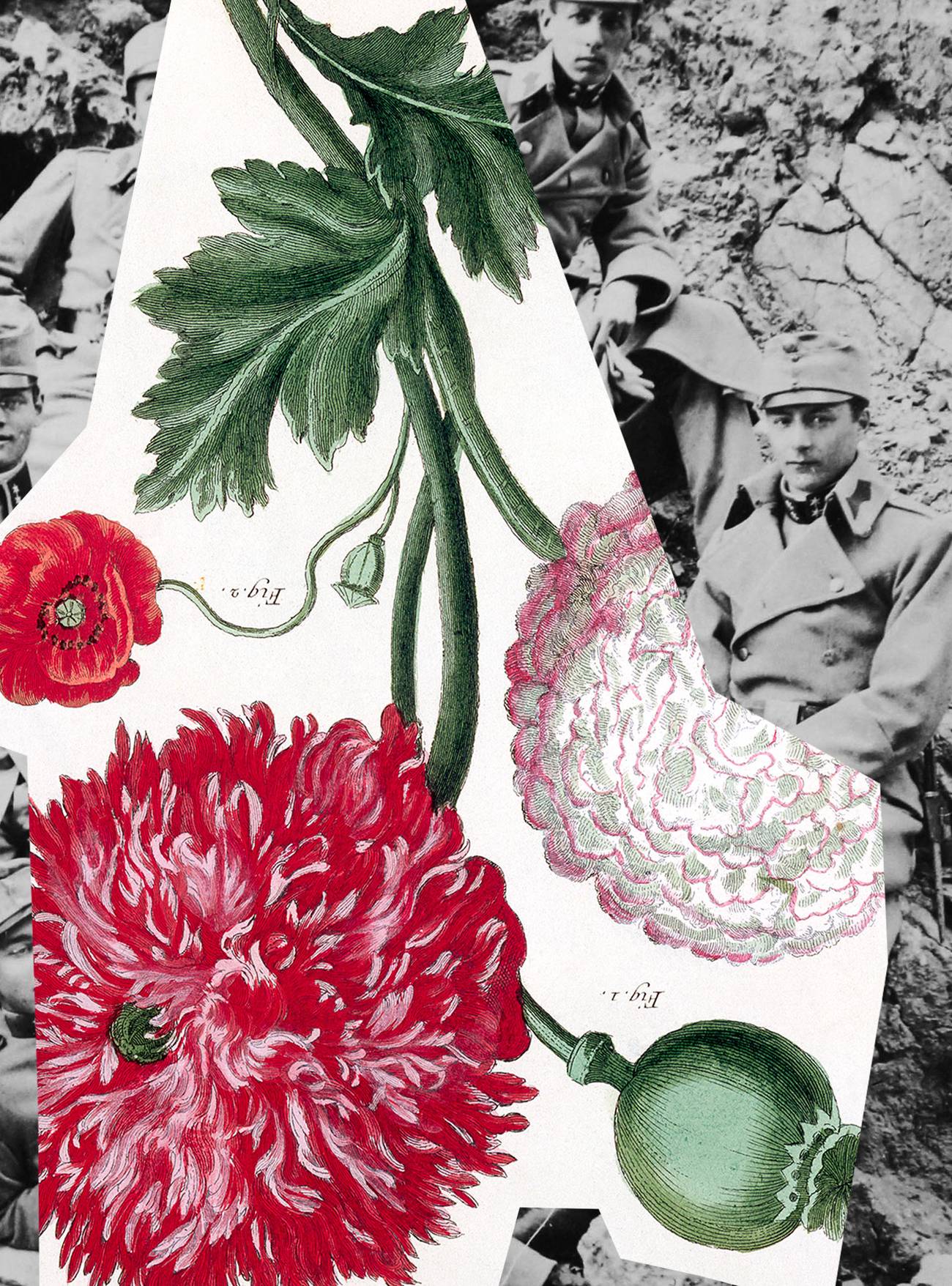

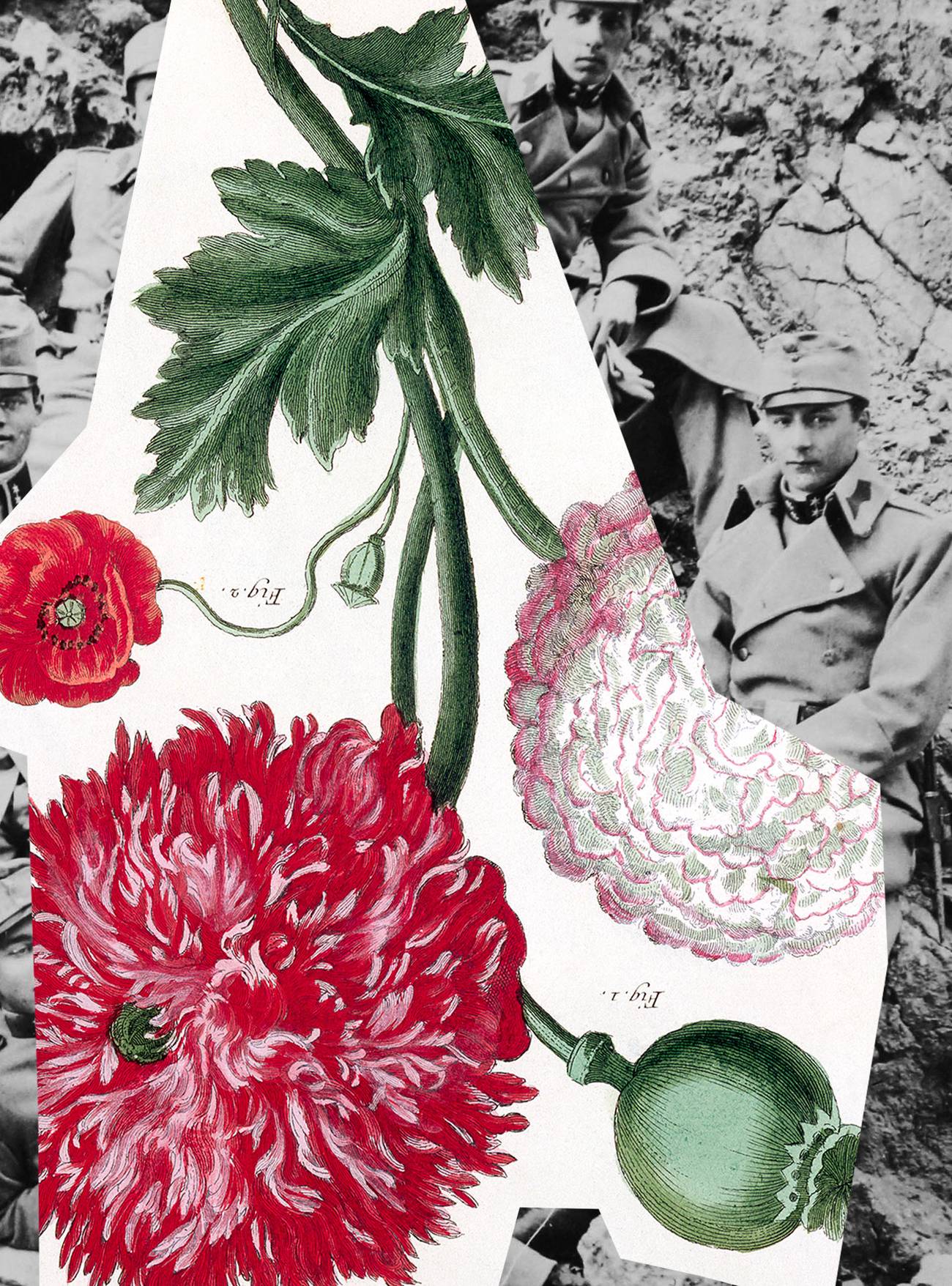

Aleksandar Hemon’s new novel is a tedious progressive frog march through the horrors of the 20th century

From its ponderous title to its inane contents, The World and All That It Holds, by the Bosnian American novelist Aleksandar Hemon, is a novel that manages to be disappointing in every possible way. But to be fair to the author, I have to say this is the type of book that I am predisposed to hate. It is an epic story of love set during a major military conflict, and it is also an adult-takes-care-of-a-poor-child-that-he-finds book. Perhaps, the earned (if torturous) sentiment of the former genre was supposed to cancel the kitschy smarm of the latter, but no dice. Instead what you have here is a drawn-out, tediously plotted work that manages to satisfy all the necessary conditions of a novel without ever seeming like it needed to be one. It felt like reading an extended treatment for a miniseries, and who knows, maybe it would work better as one. As a novel, it’s a failure.

The World and All That It Holds is a warning about what can happen when a talented author loses track of what exactly has drawn them to writing in the first place. In his early novels like Nowhere Man, Hemon, who grew up in the former Yugoslavia, displayed the facility with the English language he’d learned as an adult, detailing the cultural and geographical displacement of his sometimes autobiographical characters. In the ensuing decades, he has become a full-fledged literary celebrity, winning prestigious awards and even collaborating with the Wachowskis on the most recent Matrix sequel. He’s also, from the perspective of the establishment, politically sound: In a January New York Times interview, Hemon denounced Philip Roth for the “proto-Trumpist” novel The Human Stain, the “deplorable” American Pastoral, and for his “steadfast commitment to the many privileges of male whiteness.” The World and All That It Holds, by contrast, is obediently progressive. It has received overwhelming praise in The Guardian, the Financial Times, and The New York Times for its multicultural gay love story and its daring use of multiple languages, including a few that the author himself does not speak.

The novel’s protagonist is an apothecary of Sephardic Jewish descent, Rafael Pinto, whom we meet in Sarajevo in a laudanum-induced haze on the eve of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. War soon breaks out, and Pinto is drafted into the Austro-Hungarian army, beginning a series of encounters with war, starvation, and death that will propel him through the rest of the book. His only respite from the carnage of the trenches is his love affair with Osman, a Bosnian Muslim storyteller. The best thing that I can say about this section of the novel is that it flowed without incident. Hemon is a fair hand at depicting the more gruesome scenes of trench warfare, which he weaves in with the stories that Osman tells his fellow soldiers. Yet, by the time that Osman and Pinto are almost killed by Russians during the Brusilov offensive, then captured, separated, and reunited in the time it takes for Russia to go through a revolution, the prose begins to drag, even irritate, serving little purpose other than to keep track of the characters as they move through the upheavals of the 20th century.

Of course, this has to occur because Hemon’s main character is more beset upon than Job, and for the next 30 years, the only major massacre that Pinto doesn’t witness is the Holocaust. In order to escape the Bolsheviks and protect the young child in his care, Pinto goes east. He is chased through the desert by marauders only to end up in Shanghai, where he is roughed up by enforcers and barely evades death at the hands of the occupying Japanese forces. Many bad things happen, yet events add up so quickly that Pinto is lost in the mix and never really develops as a character. More sketch than person, he is defined by things that happen to him more than by what he does, a flaw exemplified by the central fact of Pinto’s character: his opium addiction. For stretches of the novel, Pinto is merely a doped-out spectator to history, a junkie Zelig, and the writing suffers for it:

Opium is the religion of the individual, Pinto had once quipped as Lu was rolling a pellet to be smoked. But Lu was far too seriously devoted to his task to acknowledge Pinto’s cleverness. He was now just as dedicated to the thing at hand, his somber face reliably gorgeous. Everything was so beautiful. The teak chest was beautiful, Lu was beautiful, the luminescent dragons on his beautiful face. His fingers were delicate instruments, now that he was wrangling the opium paste with two needles, as if knitting, to make it into a pellet. Everything was about to become even more beautiful.

It’s never majestic, merely overwrought. As if Hemon knew that his book was hollow, he ends it with an explanation for why we are following these characters in the first place. Generally, if you’ve gotten through an entire story and you need to attach a coda explaining why you told it, there’s a good chance you shouldn’t have. I won’t spoil the ending, but I will say that it feels like it’s there to make you really think about everything that has transpired. Unfortunately, it worked. I thought about everything I’d read and felt even more deflated.

This is generally the point where a generous reviewer would praise Hemon’s ambition for tackling such a vast subject, but I don’t know if I believe that. The preference for the large and the grandiose can be a form of vanity; it’s the hope that if there was a massive conflict the camera would turn to us to take in our suffering and pain. But of course, we know that isn’t true, especially now as everything that we see from any conflict is dispatched in fragments of fragments, making it impossible to figure out what exactly is happening at all. It would take a writer of real ambition to tell a story like that.

Hubert Adjei-Kontoh is an itinerant bookseller and fiction writer.