The ‘Lust Machine’

The cantor opposed the gramophone as a desecration of religion. The capitalist saw its potential as secular commodity. An early-20th-century tale of piety versus profit—and Zionism.

In 1910 the Odessa cantor Pinkhas Minkovsky published a book to warn of the dangers of the “lust machine.” The recording of Jewish cantorial chanting through the new medium of the gramophone, he wrote, constituted a “pornographic” response to the ills of modernity—and a threat to the Jewish people.

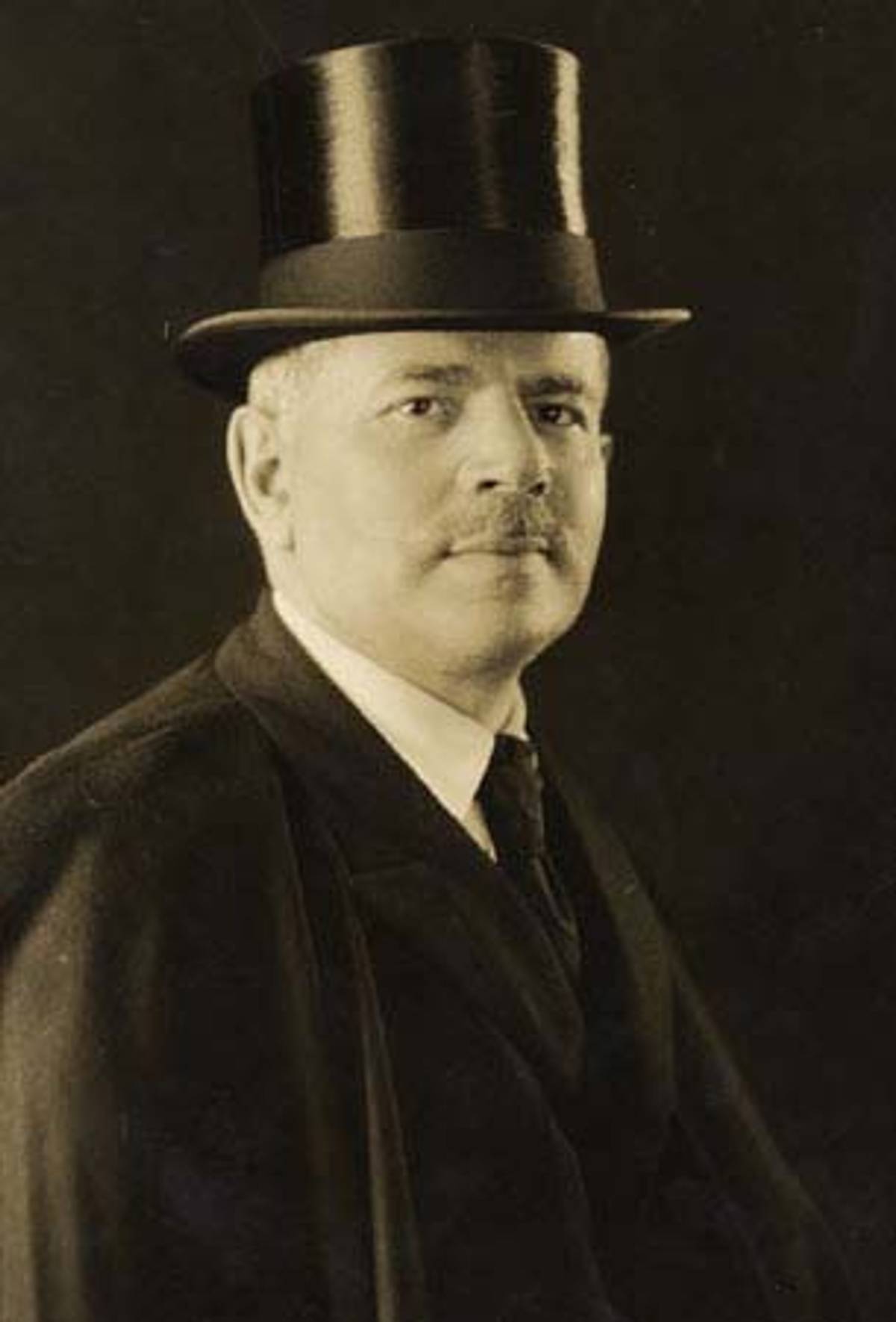

The same year, the Vilna pharmacist turned gramophone entrepreneur Wolf (Velvl) Isserlin and his brother Mordkhe opened their own gramophone factory. By his own calculation, Isserlin’s top record customers were Jews. He claimed to have sold more cantorial 78 rpm records in a single five-month period than all other genres combined over the previous five years.

Why did Minkovsky oppose the gramophone while Isserlin staked his career on it? On the face of it, the answer is obvious: religion. To the cantor, Jewish music was sacred; to the capitalist, it was a secular commodity. Minkovsky feared the desecration of Judaism, while Isserlin rushed to commercialize it. It was a classic tale of piety versus profit.

Yet such a view of both men would be a mistake. For Minkovsky, it turns out, was hardly an obscurantist rabbi plugging his ears to the howling winds of change. He read deeply in German philosophy and traipsed across the globe as a celebrity cantor. Back home in Odessa he led the city’s Zionist cultural scene. Nor was Isserlin a cynical merchant simply intent on exploiting his customers’ nostalgia. He pioneered the recording of Jewish classical music for the benefit of “the national cause,” he claimed, even at a cost to his business. In fact, both Minkovsky and Isserlin shared the same impulse to imagine and amplify Jewish nationhood in the Russian Empire through sound. At the root of their opposing attitudes toward the gramophone lay two distinct Jewish ideas about the relationship between nationalism and capitalism. Where they diverged was in the matter of the market.

We often imagine modern Jewish culture as a product of secularism mixed with a light dose of romantic nationalism. Alienated from the world of religious tradition, inspired by European culture, late-19th-century figures like Chaim Nachman Bialik, Sholem Aleichem, and Marc Chagall refashioned religious heritage, language, and folklore into new expressions of modern secular Jewish identity. Yet this before-and-after image ignores the fact that culture never moves directly from creator to public. In the decades before WWI, what allowed those artists to find their audiences and offer them new kinds of literature, art, and music was the technological and economic transformation of Jewish life in Eastern Europe. The same forces of industrialization that produced the mass immigration to these shores also ushered in an array of new market-based media in the form of newspapers, book publishing, and sound recordings.

Of those three, it is the third, sound, that we know the least about today. Who were all those Jewish customers who purchased cantorial records in the late Russian Empire? Why would small tradesmen and workers barely one step above poverty spend their money on an expensive status symbol like the gramophone? Did they snatch up religious recordings to replace religion? Or to celebrate their Jewish national pride?

The strange parallel careers of Minkovsky and Isserlin offer us a chance to answer some of these questions, and in doing so to rethink the genealogy of modern Jewish culture. In doing so, we encounter still more questions that preoccupy scholars of Jewish history today. Was modern Jewish culture born out of a revolt against ethnic capitalism? Or in celebration and amplification of it? And what would the history of Zionism look like (and sound like) viewed not only as a story of religion and politics but as one of culture and economics?

There are two stories of how the gramophone reached Russia. One is a tale of capitalism, the other a story of socialism. The socialist version begins with an opera singer turned revolutionary named Evgeniya Lineva. A star of the Russian opera, Lineva joined an underground student socialist group in the early 1880s. A few years later, she traveled to London, where she befriended Marx and Engels. Thanks to that relationship, she produced some of the earliest Russian translations of Marx’s writings.

Lineva’s radical politics led to her exile in 1890 together with her husband. Arriving in the United States, she began to perform Russian folk songs in a traveling act. In 1893 she met the American music critic Henry Edward Krehbiel in New York. Krehbiel championed the idea of a new American music based on African American and Native American folk songs. His ideas proved decisive for Dvorák’s foray into the New World. Krehbiel also introduced Lineva to the new device of the gramophone. When she returned to Moscow in 1896 she pioneered the collection of folk songs using the gramophone. She spent the next decade documenting hundreds of Russian and Ukrainian folk songs across the Russian Empire, a pursuit that had a catalytic effect on ethnomusicology there and on Jewish ethnography.

For both Lineva and her Jewish disciples, including key figures like Joel Engel and S. An-sky, the gramophone represented a tool for populist ethnography. It was a modern invention that could help salvage and preserve Jewish cultural traditions which were under threat from the onset of capitalist modernity. Indeed, the very idea of folklore itself, which 19th-century European intellectuals imagined as a people’s unique, timeless cultural heritage, was defined in opposition to the ravaging forces of modern commercial popular culture.

Yet others viewed the gramophone quite differently. The key figure in this, capitalist, story of the gramophone’s arrival in Eastern Europe was Norbert Rodkinson (Max Rubinsky), who practically single-handedly launched the commercial recording industry in the Russian Empire. His, too, is a colorful story that points to the trans-Atlantic commercial nature of Jewish entrepreneurship at the end of the 19th century.

Rodkinson was born in Baton Rouge in 1873, the son of a Russian Jewish immigrant. His father was an infamous East European charlatan, Michael Rodkinson, scion of a distinguished Hasidic family who became a radical maskil, edited several Hebrew newspapers, and published many of the first works of Hasidic literature. He was also arrested for polygamy and accused of fraud for pretending to be a miracle worker and perpetrating numerous literary forgeries. His posthumous reputation rests on his production of the first English translation of the entire Babylonian Talmud, beginning in 1897.

Rodkinson fils reportedly helped with this pioneering Talmud translation project until, according to one version of the story, his father kicked him out of the house. He subsequently graduated from the University of Cincinnati and worked his way across Europe in the 1890s as a journalist. By 1899 he had settled in St. Petersburg, where he pioneered the import of Western commercial gramophones and recordings. Rodkinson established himself there as the local agent of the German company Deutsche Grammophon, and initiated the recording of opera singers, operetta stars, military bands, and other acts. In 1906 he moved to India to organize the Deutsche Grammophon branch in Calcutta, but after a few years returned to Russia to start his own record company.

Under Rodkinson’s direction, Deutsche Grammophon opened stores across the Russian Empire and began to record Jewish artists. One of them was the famous cantor Zavel Kvartin. In his memoirs, Kvartin described how one day in 1902 he was walking home from the Warsaw Conservatory when he chanced upon a store where people were listening through headphones to gramophones. Kvartin paid a few coins and spent an hour listening, enraptured by what he heard. He immediately grasped the power of hearing music—any music—anywhere. And he instantly sensed the commercial potential for Jewish music. He asked the store owner if he had any Jewish music in his catalog, perhaps cantors. There were only two names listed—Sherini from Bratslav and Sirota from Vilna—but, explained the store owner, neither was in stock for lack of demand. No one was interested in it. Undeterred, Kvartin began to audition for various European firms. His first records straightaway proved hugely popular. Within months Kvartin was famous across Russia, and the era of the cantorial recording star had begun.

Kvartin arrived in Vilna in 1907 on an empirewide concert tour. Two men showed up at his hotel unannounced, introduced themselves as the Isserlin brothers, and invited him to a banquet they had arranged in his honor. When Kvartin asked them why they wanted to do this when they did not even know him, they responded that he had made them rich men, as they were “gramophonists” who now held the exclusive contract to sell Deutsche Grammophon records in Russian Poland, Lithuania, and Courland. Over the last five years they had sold nearly half a million records. But just in the past few months, business had simply exploded with sales of Kvartin’s records.

In a subsequent conversation, the Isserlin brothers told Kvartin that their early profits came from selling gramophones and records together as package deals. Now they planned to press their own records rather than import them from elsewhere. But competition was growing stiffer. Sales were down 50%, while anti-Semitism, economic nationalism, and czarist governmental regulation were all on the rise. Their booming business might actually be in jeopardy.

Here a broader word about the politics and economics involved in the Jewish gramophone business in Eastern Europe is in order. The economic historian Arcadius Kahan once puzzled over how Russia’s Jewish population expanded from a total of 1.5 million at the beginning of the 19th century to 5 million by its end, given that the Russian state actively squeezed Jews out of the economy through various formal and informal restrictions, especially in the closing decades of the century. His answer was that the state-driven character of Russian industrialization produced an unintended positive effect for a small but sizable number of Jews. The government’s policies of excluding Jews from capital-related industries (railways, for instance) encouraged them to migrate into new consumer-goods industries. There they more readily found credit from other Jews and a developing market that did not require state approval or facilitation.

Among consumer goods, Kahan argued, technology-related products proved particularly attractive to Jews. Governments are always slow to regulate new technology. Hence an industry like records and gramophones represented an ideal ethnic niche market for Jewish entrepreneurs. Yet Jews were not exceptional in this regard. Nor were they alone in seizing a new opportunity. Several other minority entrepreneurs entered the early Russian record industry, including Poles, Lithuanians, Baltic Germans, Ukrainians, Greeks, and Armenians. As a result, nationalist political considerations began to surface in the economic strategies for capturing different segments of the consumer market for records.

Kahan’s theory fits the Isserlin brothers to a tee. Before 1902 they ran a successful pharmacy business in Vilna. Then they joined the gramophone craze. As ambitious businessmen, they were not necessarily particular about their product. In a diverse society, it made sense to market all kinds of music to different communities. But Jewish music held a particular attraction for them as a way to build an ethnic consumer niche and capture a Jewish audience thirsting for culture.

In a sense, this was only a continuation of trends that stretched back deep into the 19th century. Commercial publishing had already revolutionized the distribution and experience of Jewish folk music in Eastern Europe. In the 1850s booksellers in the Pale of Settlement began to sell chapbooks of Yiddish songs by popular badkhonim (wedding jesters). In subsequent decades, Jewish newspapers and books exploded in popularity. By the end of the 19th century sheet music had begun to appear. And so, the market was ripe for sound recordings.

The initial appearance of commercial recordings in Eastern Europe triggered a set of strikingly polar Jewish reactions. Across the Pale of Settlement, many Jews flocked to buy records as a marvelous new source of entertainment. One visitor to Odessa in 1911 noted the incredible passion for records among the city’s younger Jewish population, especially those sold at the Isserlin store. When the ethnographers Joel Engel and S. An-sky toured the Pale of Settlement in the summer of 1912, they were shocked to find even little Jewish children familiar with the gramophone business and willing to invent pseudo folk songs on the spot to sell them. Yet in many of those towns Engel and Ansky also faced adults who denounced the gramophone as an evil device. These Jews feared that the device would steal the soul of those who sang into it much like a camera might do the same.

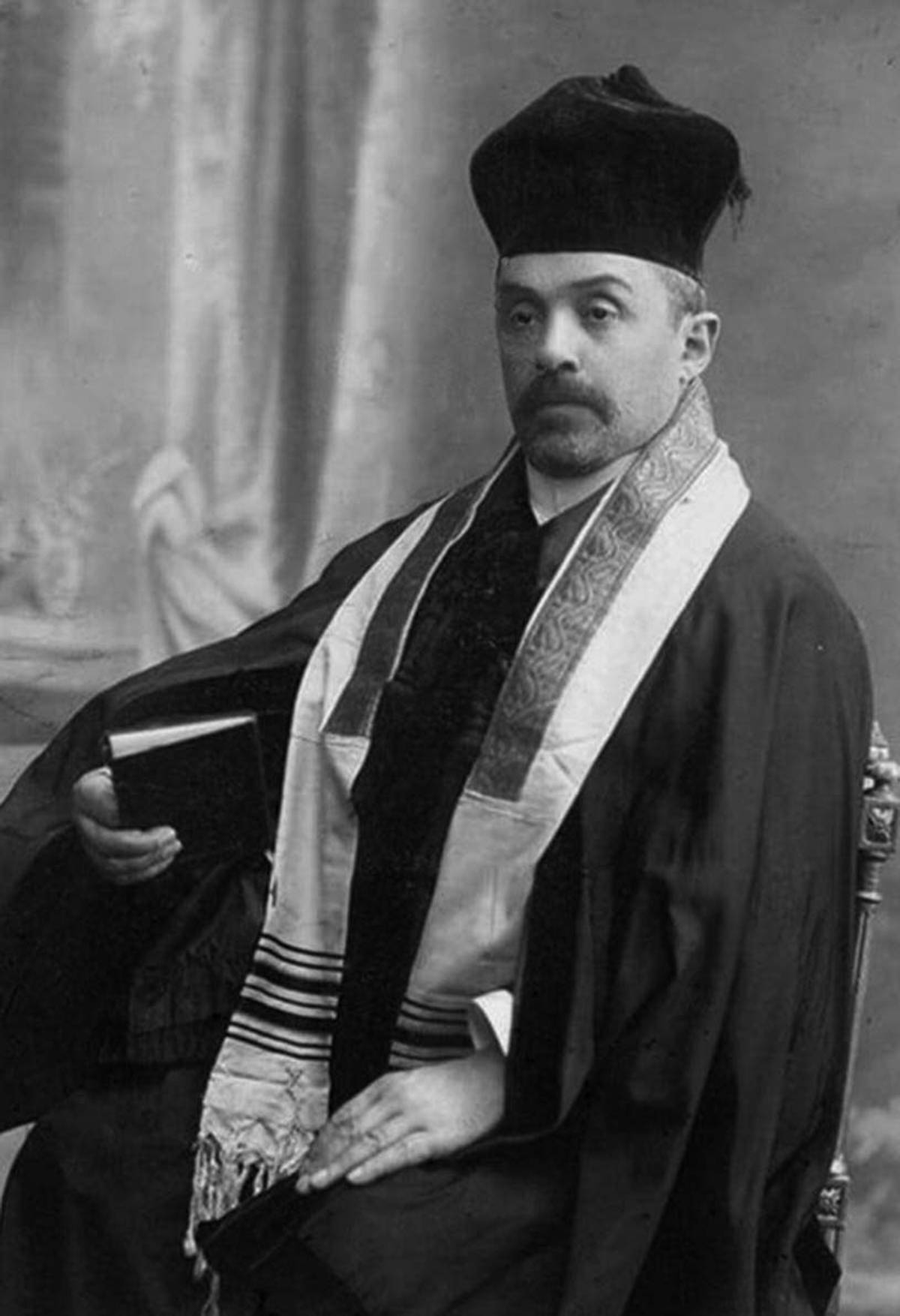

Even those with less superstitious ideas also opposed the gramophone invasion. Pinkhas Minkovsky belonged to that camp. Born in Belaya Tserkov in 1859, he emerged in the 1880s and 1890s as one of the most celebrated cantors in the world. Such was his fame that he was lured across the Atlantic to a post at the Eldridge Street Synagogue on the Lower East Side, before returning to the Brody Synagogue in Odessa in 1892. There he served as cantor and also preached the cause of Zionist national revival.

In an 1899 essay in Ha-shiloah, “Songs of the People,” Minkovsky asked why his fellow Zionists had ignored the organizing power of music:

Our nationalists, who daily invent new ways of spreading the national idea—through meetings, speeches, newspaper articles, banquets, amulets, and “Stars of David”—the majority of them also do not understand the new idea or believe in the value of music. … Do they not know, our Lovers of Zion, that there is no such thing as nationalism without music and song?

In this article, which, incidentally, was the first piece of Hebrew-language writing on Jewish musical folklore research ever to appear, Minkovsky called for an instrumentalist approach to music’s political value. Music presented Zionists with an effective means to nationalize the Jewish imagination. Yet despite this ethos of calculation, Minkovsky vehemently rejected the most powerful medium of sound transmission.

According to Minkovsky, around 1902 the German Jewish gramophone pioneer Emile Berliner approached him with a proposal to record him and his Odessa synagogue choir. Minkovsky responded with indignation. His predecessor, the legendary Nissan Blumenthal, had never once in 52 years of service sung outside the synagogue—not even for weddings or funerals. How dare Berliner ask him to sing into “a disgraceful shouting-machine”? The times had changed, responded Berliner, himself a Zionist activist who promoted technology’s role in Jewish national revival. Minkovsky vigorously disagreed:

For those of us who are truly religiously and nationally disposed, the times have not changed. Jewish synagogue song possessed a double holiness: the holiness of place [kdushes hamokem] and the holiness of time [kdushes hazman]—where and when they are sung. ... How can we profane our holy songs by putting them in a machine which knows of no place, of no time ... [and] places it before all sorts of people from all kinds of different times and different places?

Several other agents also approached Minkovsky. Each time he declined.

By 1910 the so-called “gramophone epidemic” had reached such proportions that Minkovsky felt compelled to write a book. In his 200-page Yiddish-language Modern Liturgy in Our Synagogues in Russia, he relays his conviction that the modern atrophy of Jewish religion and nationhood reflected itself in musical art. Diaspora rabbis, by which he meant both traditionalist and Reform clergy, had killed off “ancient” Jewish musical culture. He quoted Schopenhauer and Emerson at length to prove that the onus was on the Jews to acquire greater Jewish self-knowledge, to combat “assimilation,” and to maintain Jewish national and religious identity.

It was not only irresponsible rabbis and lazy Jews who were to blame. The larger culprit was the general spirit of immorality overtaking Russian society. The economic crisis and the Russo-Japanese war had brought about the rise of “two pornographic businesses”:

Illusion and gramophone. The first business involves vision and presents illuminated erotic pictures, which no man would ever look at in a healthy moral time. Now they are commonly displayed right in the open in theaters on every street of our largest cities, while a severely demoralized society looks on without shame or embarrassment. The other business involves hearing with the ear. Songs, arias, couplets from whores, drunkards, gypsies, chansonniers, and all manner of letsim [fools] [are mixed] together with the holy Jewish melodies, synagogue prayer melodies. ... The slikhot, tekhines, and kines vulgarize themselves in the confines of the gramophone.

Minkovsky’s anxieties mapped perfectly onto the larger moral panic of the post-1905 moment in Russian society, when concerns about sex, pornography, and prostitution surfaced as symbols of shifting social norms in a rapidly changing society. But his technophobia assumed a very specific form. He had no problem embracing the technological revolution of Jewish print media for his writing (though he appears to have resisted publishing his musical compositions). When it came to sound, he himself installed a pipe organ in his Odessa synagogue in 1911, a controversial act because of the organ’s deep associations with German Reform Judaism. What bothered him was the social dislocation and cultural contamination that occurred when liturgical music left its home in the synagogue. Modern Liturgy is much more concerned with “gramophone culture” than with the mechanics or ethics of recording itself.

Lurking behind these intertwined gramophone tales is a larger question of how religion and economics shaped the origins and the appeal of Zionism in industrializing Eastern Europe.

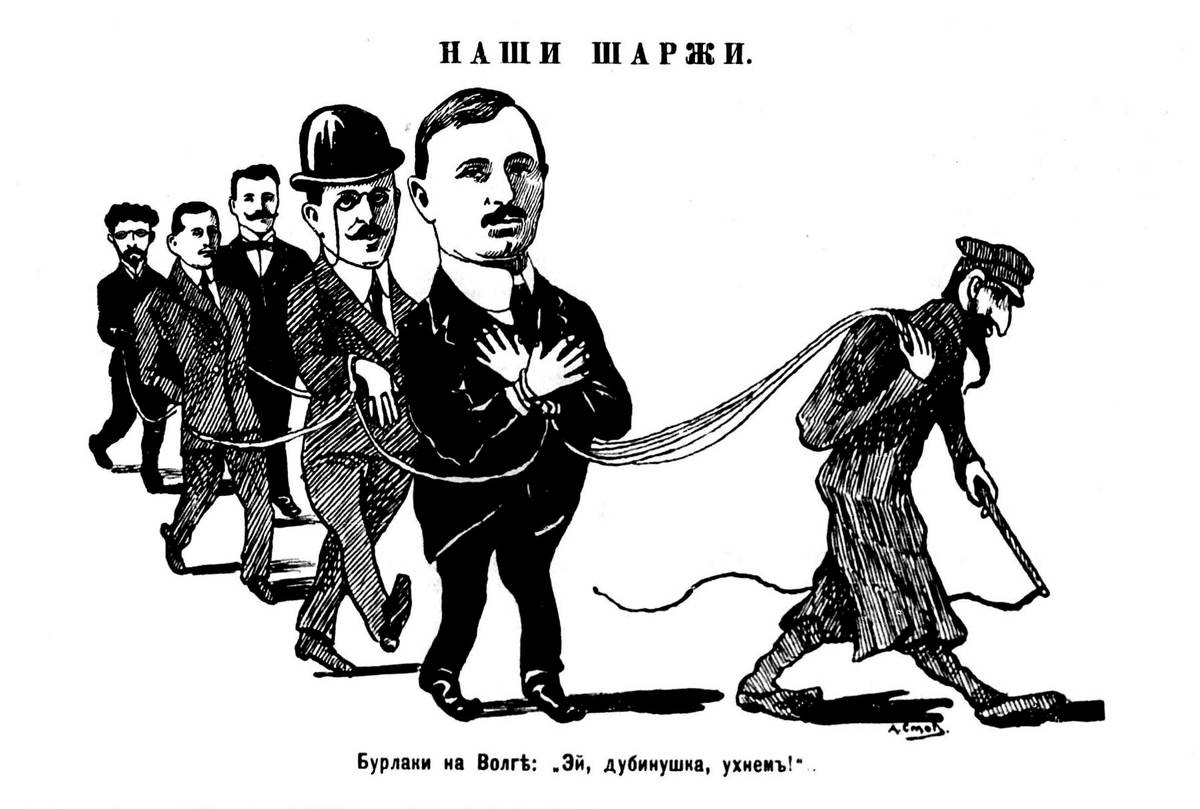

Ironically, Minkovsky shared his concerns about the gramophone’s effect on religious music with Orthodox Christian clergy, who blamed not only capitalism but specifically Jewish capitalism for their ill effects on church music. In 1914 the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs banned persons of “non-Orthodox faiths” from selling Christian religious music. Moreover, the Russian gramophone industry, despite the large preponderance of Jews involved, was itself suffused with anti-Semitism. Anti-Jewish stereotypes of Jews as cultural commercializers ruining both the gramophone industry and Russian music circulated widely.

These charges only accelerated with the dip in the market after 1912. In the summer of 1914 the right-wing Russian politician Vladimir Purishkevich petitioned the Ministry of Internal Affairs to do something about the crisis by which “the entire gramophone industry lay in the hands of foreigners, and, most of all, of Jews, who propagandize ideas inimical to the Russian national sentiment and the government’s agenda.”

Another such voice came from within the Russian gramophone industry. The trade journal Gramophone World made a specialty out of attacking the Isserlins and other “hooligans, hasidim, and tsaddikim … [engaged in] inflating prices and spreading their wide network of terror and shameless profiteering.” This was not just anti-Semitism for its own sake. It was also an extension of the rampant economic nationalism of the late Russian Empire. The Polish anti-Jewish boycott that began in 1912 was an extended prelude to the “cold pogrom” of interwar Poland—an effective nationalization of Polish economic life that unleashed a devastating effect on Jews. Beginning in 1914 Polish nationalists organized a boycott of Jewish record stores, urging fellow Poles to buy only “pure Christian” and “pure Polish” records. That same year, rumors swept the gramophone industry that Jews would be banned from renting shops at the major Nizhny Novgorod fair, which would be disastrous for Jewish gramophone entrepreneurs.

The events of the 1910s led the Isserlin brothers to three simultaneous moves that bring the story full circle. First, they attempted to organize a syndicate, called the League of Fair Trade, to confront the economic downturn (and possibly the anti-Semitic boycott). They claimed it was needed to “normalize prices” in the industry. Critics said it amounted to a cartel that would consolidate control in their monopolistic hands. It also led to more anti-Semitic charges that these “Vilna priests” of the gramophone wished to turn everyone else into their “slaves.”

Second, they employed the media. In 1914 they launched their own journal, Musical Echo, to promote their cause. Its pages present a fascinating view of an attempt to build a cooperative of Jewish gramophonists and their industry allies.

Finally, in the spring of 1914 the Isserlin brothers announced a new series of Yiddish-language recordings of Verdi’s Rigoletto, Rubinstein’s Maccabees, and Rossini’s Barber of Seville: “the first attempt to present classical music in the Jewish language.” At the same time, the Isserlins approached a group of Jewish composers in St. Petersburg, the Society for Jewish Folk Music, with a proposal to issue new recordings of original Jewish musical compositions:

As Jews, we naturally devote much of our attention to Jewish repertoire, in response to the passionate hunger on the part of the Jewish masses for Jewish music. We consider the gramophone to be one of the best means of bringing music to the national masses. In connection with this aim, the existing Jewish catalogues, of course, cannot satisfy us, for they so far consist largely of recordings catering to the primitive tastes … and nearly all the existing catalogues are full of the names of various Yiddish operettas of a certain genre ... shund-songs, that do not nurture a healthy interest in the public for good music.

As Isserlin went on to explain in his letter to the St. Petersburg composers, he and his brother wanted to help them promote a “wholesome Jewish repertoire.” He further claimed that they did not expect to make a profit: “On the contrary, we know, truthfully, that this initiative would bring unproductive expenditures and even losses, but we have resolved to bring it to life as helpful in national terms regardless of the profitability of the enterprise.”

The composers in question were committed nationalists dedicated to the idea of national cultural revival. Through the Society for Jewish Folk Music, they published a widely popular songbook for home and school and a series of art music compositions. Yet they proved skeptical of explicitly commercial ventures of the kind proposed. As they wrote back to Isserlin, previous negotiations with other record companies had faltered on concerns about copyright and aesthetic purity. They insisted on maintaining a strict separation between their art music and popular shund material in terms of marketing.

In reply, Isserlin assured the composers’ representative that he well understood their fears. All care would be taken to promote the national cause without undermining Jewish cultural integrity. The discussions dragged on until the outbreak of the First World War curtailed the project. In 1915 both Isserlin brothers fled the German invasion of Vilna and resettled in St. Petersburg, now Petrograd, where they reentered the pharmacy business. After the Russian Revolution, they tried to eke out a living in communist Russia in light manufacturing and chemical production before disappearing from the historical record in the early 1920s. While the former bourgeois capitalists tested their luck under Soviet Communism, Minkovsky fled the Bolsheviks. He died in Boston in 1924.

A businessman who willingly seeks out a loss, a capitalist who disavows the profit motive: These are counterintuitive propositions. For that reason, when I first wrote about this failed joint venture in my book, The Most Musical Nation, I dismissed Isserlin as a shameless hack. His entreaties struck me as disingenuous attempts to expand his market share on the backs of Jewish composers. By contrast, I had no trouble imagining the conservatory-trained musicians of St. Petersburg as fussy aesthetes who feared that commercialization would erode their national cultural revival. Now, however, I would qualify my skepticism regarding Isserlin, and tweak my reading of Minkovsky. For, in truth, it is possible to view both Isserlin and Minkovsky as two distinct faces of Jewish nationalism’s interactions with rising capitalism in Eastern Europe.

We are in the midst of a new boom in scholarship on the history of modern Jewish nationalism. Not content to read history backwards from the vantage point of 1948 or 1967, historians have reexcavated a host of thinkers, political parties, and plans for Zion and the Jewish diaspora, especially in Eastern Europe. Taken together, these studies challenge our assumptions about Jewish ideas of nation, state, and territory in the five-decade period between 1897 and the end of World War II. They show, among other things, just how surprisingly late in time Zionists settled on the idea of a sovereign Jewish nation-state in Palestine as the end goal for Zionism.

Yet besides the endpoint of the story, we also need to rethink its beginning. Lurking behind these intertwined gramophone tales is a larger question of how religion and economics shaped the origins and the appeal of Zionism in industrializing Eastern Europe.

The place of religion in the early history of Zionism is, of course, a long-standing topic of scholarly debate. Was Zionism a brazenly secular revolt against religious tradition? Or a messianic religious impulse stealthily transposed into the modern idiom of secular politics? Neither, in the case of Minkovsky. The Orthodox cantor was every bit the Zionist, but he came to his nationalist convictions not as a replacement for a lost faith nor out of longing for a messianic redemption. He was, more simply, a Jewish Romantic. His aesthetic faith explains his attitude towards the gramophone. To him sound was a preserve of religious and national identity, a sacred precinct that had to be protected from modernity’s encroachments. The gramophone industry symbolized the dissolution of Jewish nationhood in the urban marketplace.

Minkovsky’s ideal of nationhood grew out of the synagogue. The sacred chants constituted the repository of Jewish national pride and a connection to the ancient past; they formed part of the crucial link between modern “religious culture” and ancient nationhood. Other ties, such as land and politics, had already been severed by history. In short, the synagogue was the place of the rebirth of Jewish nationhood, and the sound of the synagogue required careful aesthetic cultivation, not mass popularization.

Recent years have also seen the return of economic readings of early Zionism. This scholarly move shifts away from the religious imagination toward the materialist bases of Jewish political mobilization. In short, some historians now argue, it was not the yeshiva or the synagogue that birthed Zionism but the marketplace and the factory. The rabbis might promise the Jews spiritual deliverance, and the state might dangle legal rights. But neither could provide the means to combat economic devastation, material poverty, and pure hunger in modern Jewish Eastern Europe.

The growth of market capitalism exacerbated this trend. Urban industrialization in the northern regions of the Pale of Settlement pushed millions of Jews to leave the Russian Empire for the United States from the late 19th century onwards. Those who remained faced a new kind of economic nationalism, with boycotts and cold pogroms a fact of life by the 1910s. We know that this economic nationalism served a key role in constituting Polish and Russian national identity in the same time period. There is no reason not to assume the same held true for Jews.

This, then, is the story of Isserlin. While Minkovsky recoiled from market capitalism, Isserlin embraced capitalist nationalism. For him, sound was part of a multiethnic modern world in which every people was simultaneously cultivating its own national identity and competing for market share. Sound was a front in an economic battle for Jewish survival. Even if the market would not provide immediate financial rewards, its reach and power would help the cause of Jewish music and, eventually, Jewish economic fortunes.

Who was right and who was wrong? Minkovsky was certainly correct in arguing that any Jewish politics would fail without music. Every social movement needs a soundtrack. But it is not enough to choose the right songs. Without an effective medium to reach its audience, music remains marooned in the minds of its creators. Isserlin grasped that truth even as he sensed a promising business prospect. Yet his own experience revealed how unstable capitalism could be for vulnerable minorities. The same powerful economic forces that unleashed new opportunities for national pride and personal profit also triggered nationalism’s potent dark side. The market turned business competition into political conflict. Those tensions animated the origins of Zionism in Eastern Europe much more than we previously realized. And we need to remember them today not only because of their historical value, but as a story of sound and politics that echoes powerfully down to the present.

Adapted from James Loeffler, “The ‘Lust Machine’: Recording and Selling the Jewish Nation in the Late Russian Empire,” in François Guesnet, Benjamin Matis, and Antony Polonsky (eds.), Jews and Music-Making in the Polish Lands, volume 32 of Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry (London: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2020), © Institute for Polish–Jewish Studies 2020. Published by permission.

James Loeffler is the author of The Most Musical Nation: Jews and Culture in the Late Russian Empire and co-editor of The Idelsohn Project.