The Making (and Remaking) of a Jewish Jazz Masterpiece

Fifty years ago this month, a Jewish youth group issued a remarkable ‘concert service in jazz’ album featuring Herbie Hancock and other greats titled ‘Hear, O Israel’—but the composer hated it

During winter break of his sophomore year at Brown in 1967, Jonathan Klein traveled to New York with his French horn, baritone sax, and an unusual score he’d written several years earlier.

An aspiring composer and son of a Reform rabbi from Worcester, Massachusetts, Klein had taken a traditional Jewish prayer service—complete with candle blessing, Kiddush, psalmist meditation and the Sh’ma—and set it to jazz tunes, from snappy to bluesy to bossa nova and even modal. Congregations around New England—including his father’s—enjoyed his adaptation, and now Klein was getting a chance to record the work, as part of a recruiting effort by the National Federation of Temple Youth to attract new members.

A producer and sound engineer rented a recording studio on East 14th Street in Manhattan. Klein had scant rehearsal time and all of six hours to pull the session together with a pickup band of professional musicians, a pair of female opera singers and the NFTY rabbi, David Davis, to read the spoken portions in English and Hebrew. There wasn’t enough money for a second booking or multiple takes, especially since one of the musicians was getting double the usual union scale. Creative differences flared as the day wore on.

Somehow, NFTY got its album—a 38-minute, nine-cut recording titled Hear, O Israel. A few hundred copies were pressed in March 1968 and distributed free to local chapters and shuls as a way of showing Jewish high schoolers that services could be hip—the LP’s blurry cover photograph featured a Torah against a tomato-red backdrop, flanked by a trumpet, sax, and French horn. There was virtually no retail distribution or radio airplay; the record didn’t carry a catalog number, just a NFTY stamp on the label.

Fifty years later, Klein gets testy when reminded of the project. A commercial and TV composer who taught film scoring at Berklee College of Music until his retirement in 2014, he prefers not to discuss the recording, though given a chance he’ll count all the ways it bombed. “The two singers were totally wrong for the job, and whoever transposed the tenor sax part pushed it up an octave too high, which threw the voices off,” Klein said from his home in Framingham, Massachusetts, as if recalling a root canal. Mostly he blames himself. “There were amateurish writing mistakes, and the arrangements were weak—it took me years to compose well for vocals. Plus, I never should have performed—my horn sounded flat and didn’t mesh with the others. It was a harsh lesson to learn as a student not to play on your own project.”

Klein has every right to go hard on his early effort. But for those who’ve had a chance to hear it, the original was no failure. For despite the bloopers and missed assignments, Klein had one amazing stroke of good fortune in the musicians he landed that day, which rescues Hear, O Israel from the scrapheap of jazz vespers.

Out front on trumpet and flugelhorn was Thad Jones, member of a prominent jazz family whose brothers were pianist Hank Jones and drummer Elvin Jones; in 1967 Thad was drawing attention for the sassy big band he had recently formed with drummer Mel Lewis; it would soon become one of the biggest acts in jazz. On alto/tenor saxophones and flute was Jerome Richardson, whose credits included recordings with legends Cannonball Adderley, Charles Mingus, Milt Jackson, and Kenny Burrell, along with top singers Sarah Vaughn, Abby Lincoln, Dinah Washington, Betty Carter, and even Harry Belafonte. The rhythm section was anchored by bassist Ron Carter and drummer Grady Tate, two of the steadiest beats in the business, with hundreds of albums between them and long careers ahead.

But the leader of the date—reflected by his double paycheck and extended playing time—was pianist Herbie Hancock. Still a member of Miles Davis’ seminal quintet and known for breakout tunes like “Watermelon Man” and “Maiden Voyage,” Hancock was a 27-year-old jazz thoroughbred, perhaps the most in-demand pianist in New York. He’d already had a small string of hit albums under his own name on Blue Note, but was busy freelancing as a sideman for other first-tier labels including Atlantic, Columbia, Verve, A&M, RCA, and Cadet. Having Hancock at the keyboard, with his inventive chord choices, harmonies, solos and rhythmic comping, was guaranteed to produce superior recordings—as it already had for such jazz greats as Freddie Hubbard, Stan Getz, Wayne Shorter, Kenny Dorham, and Donald Byrd. That NFTY was able to secure Hancock and his mates for a private-label album of Jewish liturgical verses cooked up by a no-name college sophomore was a major coup.

***

I first became aware of Hear, O Israel around 2002, via Fred Cohen, owner of the Jazz Record Center, an invaluable resource for rare and out-of-print recordings housed in a small office building in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood. Cohen knew I was a Hancock fanatic and mentioned he could obtain a copy through his pipeline of collectors—this was before eBay and Amazon made anything accessible. Although a prolific performer, Hancock has produced far fewer albums as a leader than his peers—including fellow piano icons Keith Jarrett, Chick Corea, and McCoy Tyner. The idea that he’d headlined a never-released 1960s record of Jewish prayers was riveting, which is why I didn’t flinch in coughing up $175 for the pristine LP Cohen sourced. But I no longer owned a turntable, so had to pay another $30 to have the vinyl version converted to CD at Gryphon Used Books on West 72nd Street.

The album did not disappoint—and still doesn’t every time it pops up on my iPod. From the opening dance-like “Candle Blessing” to the final up-tempo “Benediction,” Hear, O Israel is a first-rate modern jazz suite, with inspired source material performed at a high level by some of the finest jazz musicians of the day.

Sure, some of the vocals are garbled and the rabbi’s enunciations grandiose—what rabbi’s aren’t? The pacing is off in a few places, including several abrupt endings. And that French horn solo on “Mi Chamocha”—it sounds distant and sluggish; no wonder Klein winces thinking about it a half-century later. But he’s carried along nicely by Hancock, who lifts the entire group with brilliant solos, intros, and chord voicings that would be more widely referenced today if the recording weren’t so obscure. A few of the cuts are barely a minute long, which is a shame because they start out with promise. If only Herbie had taken a solo after Jerome Richardson’s flute on the spritely “Kiddush.”

It’s not a stretch to say that Hear, O Israel captures a fleeting moment near the end of an era in post-bop jazz, and reveals a small missing link in the career of one of its masters. Within a year after NFTY handed out its scant stash, Hancock would be among the prominent players joining Miles Davis in a Columbia recording studio for the making of In a Silent Way, a beacon for a new type of jazz fused with electrified rock that was morphing into funk, disco, soul, and other pop styles that was pushing jazz into more commercial directions. By 1969, Hancock would leave Blue Note for the bigger Warner Bros., using electric keyboards and trying out a variety of unjazzy sounds and polyrhythms that would propel him to superstar status with his 1973 album, Headhunters.

But in 1967-68, jazz was still mostly sticking to its side of the street, which limited its popular appeal but also gave so many recordings from those years a stylistic purity that some critics feel represented a kind of heyday. Hear, O Israel belongs in that last chapter of the ’60s sound typified by Blue Note—a mostly acoustic, small ensemble playing original compositions powered by crisp, straight-ahead rhythms and simple, if clever, arrangements. That everything was wedded to a set of Hebrew prayers only added to its honesty.

It’s worth noting that in early March 1968, less than three months after recording Hear, O Israel, Hancock went into a Blue Note studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, leading a sextet that included Ron Carter and Thad Jones, to produce one of his greatest albums from that period, Speak Like a Child. It was released that summer and became an instant classic, with amazing piano work driving a set of first-rate tunes, including “Riot,” “The Sorcerer,” Ron Carter’s “First Trip,” “Toys,” and the title track. A side-by-side comparison of the two albums does not diminish Hear, O Israel, despite the obvious production differences. Not only does the style of play place each record from the same peak time frame, but there’s a similar spontaneity and upbeat feeling to both—it could well be that Hancock carried a bit of Klein’s project with him in conceiving the latter album, including an elegiac ensemble piece called “Goodbye to Childhood.”

Israel compares favorably to several other religiously-rooted jazz recordings from that era that likewise hold up decades later. One was a 1963 Blue Note album by trumpeter Donald Byrd called A New Perspective, paying jazzy tribute to old-time spirituals and gospel hymns. It, too, is enhanced by Hancock on piano, as well as a rousing chorus of Pentecostal singers. The other is a live Episcopal church service captured at San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral in 1965—transformed by a trio led by pianist Vince Guaraldi, who shortly thereafter gained lasting fame for scoring the Peanuts TV specials. Complete with sounds of coughing and page-turning, as well as a bishop’s greeting, invocations of “Christ Our Savior” and a 68-voice children’s choir that could have included Linus and Charlie Brown, Grace Cathedral (Fantasy Records), is also an extraordinary merging of jazz and sacred text. Hear, O Israel has a rightful, Jewish place alongside both of these outstanding recordings.

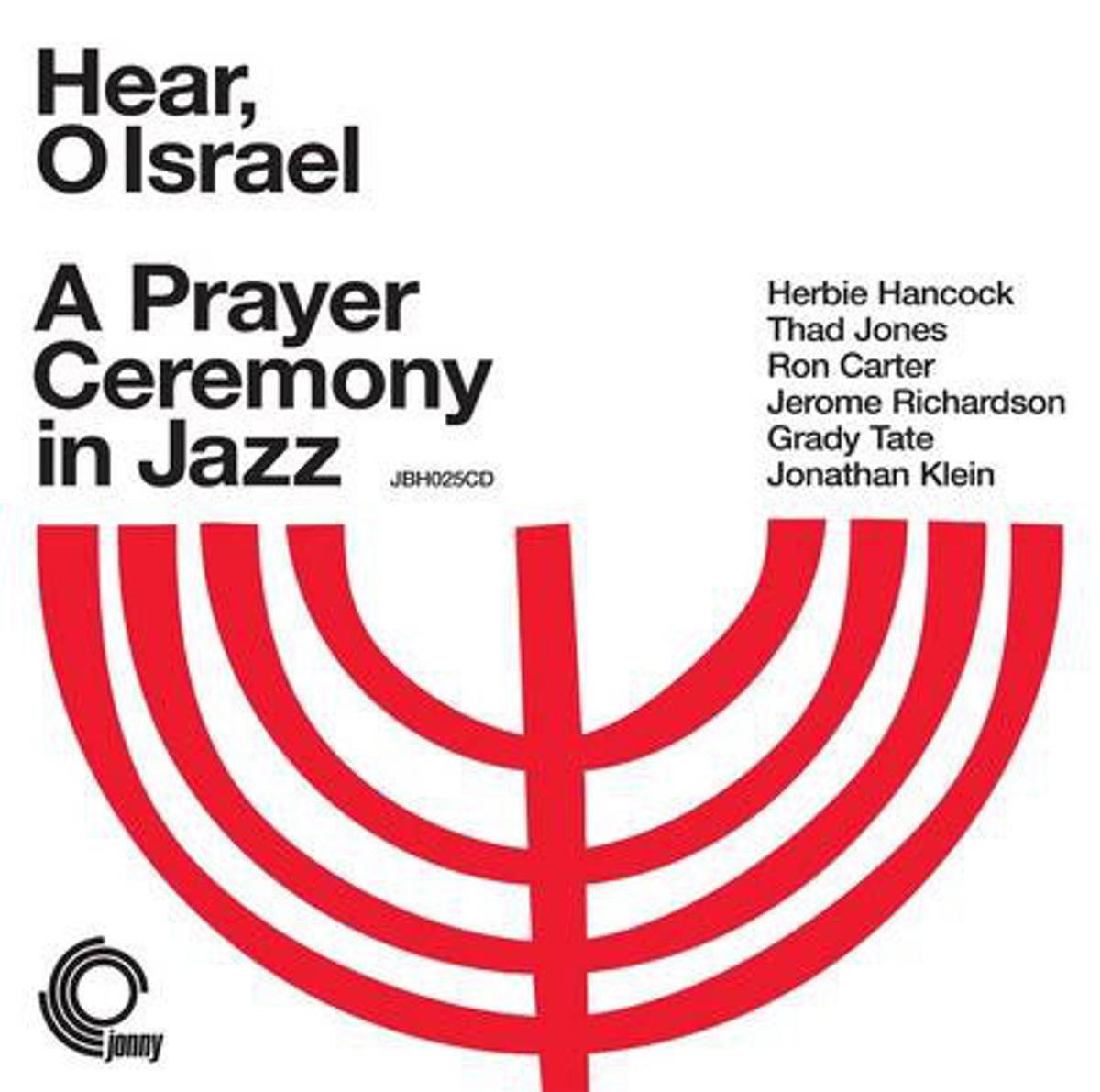

Although the original LP has disappeared even from auction sites, you can buy a CD or even a vinyl version of Hear, O Israel online. Credit an enterprising British DJ and promoter called Jonny Trunk (real name Jonathan Benton-Hughes), who swooped in a decade ago and obtained rights to the original 1968 recording from the union—and no, that’s not the musicians’ union, but the Union of Reform Judaism, NFTY’s nonprofit parent. A recent search on Amazon found used copies for $110, while a mint version was selling for $411, reflecting Trunk’s shrewd move of keeping supplies limited—his label bills it as “The Secret Herbie Hancock Album.” But you can also listen to the whole recording free on YouTube. Trunk switched out the homemade cover for a more modern graphic depicting an illustrated red menorah against a white backdrop because, as he put it kindly, the original sleeve image “is so very terrible.”

Someone sent Jonathan Klein a copy of the Trunk reissue a few years ago, though he swears he hasn’t cracked the cellophane covering the CD. For him, Hear, O Israel wasn’t properly realized until he recorded a 1992 redo for the Milken Archive of Jewish Music, which for various reasons was kept under wraps until 2011. That version can also be sampled free on Spotify or YouTube and includes five minutes of Hancock-Carter-Tate trio work from the original spliced into Klein’s updated reworking of the prayer service. Not only was that the limit of material that could be used without paying royalties, it was all Klein felt worth salvaging from the 1967 session.

***

For Ron Carter, the session may have been just another day in the studio, but that’s not to say he approached it with anything less than his usual sense of purpose.

“Every day, on every recording, it’s a different band, under a different leader, with different concepts, different keys, and instrumentation,” says the 80-year-old Carter, whom Guinness certifies as the world’s “most-recorded jazz bassist.” Thus, when asked which of the more than 2,200 albums he’s made are among his favorites, he answers diplomatically, “Whichever ones they called me to come in for.”

In the end, the scale probably tipped and you had an album that was more jazz than Jewish.

But Carter acknowledges that performing with Hancock has always been special, and in the mid-1960s their bond was especially close as part of the Miles Davis group. “Herbie raises the level of music in an instant—that includes me, but also drummers, singers, whoever he’s working with. He has the desire and ability to listen and anticipate what comes next, or what should come next. He hears the other musicians so that his notes and chord choices and solos are integrated with everyone else. That’s a true leader.”

That Carter never got to solo on Israel doesn’t bother him a wit. “I’ve never been one of those players hanging back behind the palm tree waiting for my spotlight,” he told me in a velvety soft voice from his apartment on New York’s Upper West Side. “My role has always been to bring a dynamic to the band and to help make the whole group sound like it should and also have fun. I take whatever solos I want in my living room and I always sound great!”

Hearing that the composer has less than a four-star regard for this off-label recording, Carter responded, “That’s his honest opinion, but from what I remember the music was well-written and had a lot of movement and changes, which I always appreciate. The singers may not have been jazz-trained but they were right there and added a serious, reverential quality to our work. I remember heading home that day not only feeling that we’d done the job, but we were adding something new to the normal jazz library. In fact, I’ve given a copy of the recording to some cantors and rabbis I’ve met to see how they react. They were astonished by the quality of the tunes and the force of the music. So I don’t think you can say it wasn’t a success.”

***

There was another key hand at work helping shape Hear, O Israel—thanks to composer Charlie Morrow, who was called on to pull the album together. The album’s official producer was an Italian-born music publisher named Raoul Ronson, whose company, Seesaw Music Corp., licensed the vocal parts, paid for the studio and contracted with the musicians. But in addition to hiring Ronson and bringing in all the players, Morrow called on another of his contacts to run the soundboard as recording engineer—Jerome Newman.

“Jerry was a legend,” said Morrow, speaking recently from the Netherlands between performance projects throughout Europe. No disputing that: While still an undergraduate at Columbia in the 1940s, Newman was known for lugging a portable disk-cutting recorder to Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem, where he captured early bebop sets by Charlie Christian, Thelonious Monk, and Charlie Parker. Although he later mastered recordings of flamenco guitarists, ethnic Greek and Arabic folk tunes, Beethoven symphonies, and Flemish chamber works, Newman, who died in 1970, is best remembered for his jazz output, including studio albums by Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, Pharaoh Sanders, Oscar Pettiford, and others.

“It was Jerry who ensured that the session was ‘on brand,’ ” Morrow said. “A quality recording depends on the lineage and legacy of those at the engineering controls—that’s what made all those Blue Note albums so distinctive under the care of Rudy Van Gelder. Jerry likewise knew all the technical aspects within the studio setting needed to create a strong jazz sound.

“Keep in mind,” he continued, “because of the cost constraints, this was a straight live-to-stereo recording. There was no multitrack machine, where you could balance the constituent parts in post-production. Every take was the way it was—what you got is what you got. Having Jerry engineer the work was further proof that I always wanted to be the least talented person on set. There are some collectors who would cherish this recording solely on the basis that it was one of Jerry’s works.”

Still, Morrow considers the session with mixed feelings today. In a musical career loaded with highlights—critically acclaimed rock operas, sound installations, and symphonic works, plus a thriving commercial business that includes film scores (Ken Russell’s Altered States) and ad jingles for Coke, Hefty Bags, and the famous rat-a-tat-tat percussion track behind WINS radio slogan, “You give us 22 minutes, we’ll give you the world”—his total absence from any association with Hear, O Israel feels a bit of a slight.

“I never got paid, for one thing,” he said. “And you could say there were a few bad feelings that day. Jonathan wanted more creative control and probably felt patronized when Herbie took over his tunes. He wasn’t exactly receptive to my ideas and recommendations—we had some dicey moments with the arrangements, and he was struggling, especially with the time limitations we had to work with, so he may have blamed me for any rough patches. I’m certain he faulted me for the singers, who happened to be world-class vocalists—Antonia Lavanne and Phyllis Bryn-Julson. The fact is, as soon as Jerry put Jonathan into the mix, he was going to be dialed back to let the other players do their thing.

“For whatever reason, no one ever reached out to me afterward, not even to share a copy of the album,” Morrow added. “I knew it was a unique undertaking based on Jonathan’s remarkable idea and this exceptional coming together of talent—but it just never blossomed in my life or became something to add to my CV, even though I was the actual producer.”

Prominent Hollywood composer Michael Isaacson, a former NFTY counselor who was present at the original 1967 date, remembers the tension at play in the Stereo Sound studio that day. “Jonathan was definitely in a post-adolescent state,” he recalled. “He had his French horn and his baritone sax and wanted to contribute, but frankly, his playing got in the way of some really great jazz.

“I can understand his frustration,” Isaacson continued. “Charlie hired two singers who were terrific at opera and new music, and could sight-read any score, but they didn’t have a feel for jazz or what Jonathan had in mind for the piece—they were basically singing Hebrew phonetics. Meanwhile, you had these killer musicians who came together for one six-hour project. They’d never seen the material before and were tolerating the prayer verses and the first eight or 16 bars up front so they could get to what they did best. Essentially, Herbie and the others were playing jazz on changes—and that bothered Jonathan. He felt Charlie was mollifying him and there wasn’t a proper alignment between one text and another, or with the music. Without question, it’s a landmark recording and a noble experiment deserving of a wider audience. But in the end, the scale probably tipped, and you had an album that was more jazz than Jewish, which is OK, but it’s not how it was supposed to go.”

Rabbi Davis, the former NFTY director who commissioned the album, doesn’t see it that way. “Was it a perfect recording?” he asked. “Maybe not. Jonathan zeroed in on the negativity, but he may not have realized what we accomplished. It made a real stir in our community. It got people talking around the country, and it had a lasting impact on many young people and artists.” One of those he remembers was the late Debbie Friedman, whose folky reworking of conventional prayers and songs became a staple of many Reform services. “Debbie was a folkie, but she loved our jazz album and said it helped her realize how open the prayer service was to different musical styles and voices,” Davis said.

***

Klein may have tried to bury any memory of the original recording, but he had continued to tweak his concert piece, at least for a while. In 1969, having graduated from Brown and readying to begin teaching at Berklee, he performed what he calls “Version 2” of the service at Boston’s Temple Emanuel.

His group included two Berklee scholarship students who had recently emigrated to the U.S. from the Czech Republic—Jan Hammer on piano and George Mraz on bass, along with young Berklee alum, drummer Harvey Mason. All three would go on to achieve true jazz stardom. Klein felt he’d improved the work considerably, based on his own further study of arranging and harmony. “That’s one I wish we’d recorded,” he said wistfully.

Then the demands of a career took over. After a stint at Berklee (where his students included the guitarist John Scofield), he left in 1975, initially to score animated films, among them a popular children’s series called Captain Silas used in schools and libraries. He had jobs with PBS and joined a cover band, playing keyboards in clubs and at functions around Boston six nights a week, and even appeared on several disco albums. He wrote jingles and incidental music for TV ads selling Raleigh bicycles and Girl Scout cookies, and performed with a fellow Brown alum named Susan Bennett, a sometime jazz singer and commercial voice-over artist who later secured her place in popular culture as the comforting voice of Apple’s Siri.

That’s the secret success of the rerecord—the vocals have real heart and soul, and weren’t going through the motions from a score sheet.

He also produced several other Jewish scores, including a piece called “Sacred Times and Seasons” commissioned by a synagogue in Brooklyn, with a woman cantor—not a common fixture at a 1970s shul. (Klein maintains a modest personal website with a sampling of some of his work.)

In 1989, Klein returned to Berklee as an associate professor in film scoring, confident in his chops and starting to think about revisiting the Israel service. “I’d learned so much about arranging during those years, even if the basic structure and melodic core of the work was the same,” he said. “When Michael Isaacson called me out of the blue in 1992 offering to make a new recording for this new Milken Archive, I felt ready to give it another try. Michael had become a big-deal Hollywood composer. I was excited to take a fresh pass at the work for his new archival project. He’d been present for the earlier record and knew it had defects, so I trusted he’d let me get it right.”

This time, Klein would get to call his own shots. He began by creating a Version 3 of the service, with four Berklee-trained singers (two males, two females), double woodwinds and a trombone added for a deeper sound. He reharmonized the vocal parts, adjusted the keys and recruited a full Berklee lineup of musicians, including Michael Rendish, a fellow pianist from the film department, and trumpeter Herb Pomeroy, one of the school’s most revered instructors, whom Klein called “the greatest musical influence in my life.” And despite being a more polished player, “I definitely wasn’t going to perform on this one,” he said.

Taking several months to put the new elements in place—including ample rehearsal time—Klein booked a studio on Boylston Street near Fenway Park in late April to record the group’s effort, with Isaacson on hand to gently guide the session.

“I sat in the booth and made some suggestions, but this was basically Jon’s baby,” Isaacson recalled. “He was mature enough to put his ego aside and place the piece first. And he did an absolutely wonderful job, with people who were well prepared and who worked well together.

“I remember on break saying this was pretty different from Herbie and Thad Jones, but that was the point,” he continued. “It was a more coherent, unified work now—the singers had gorgeous diction and knew the Hebrew. To me, that’s the secret success of the rerecord—the vocals have real heart and soul, and weren’t going through the motions from a score sheet. The whole piece seemed more considered and truer to Jon’s original conception of a jazz service that was devout and yet had an improvisational feel. I was proud to have been part of it.” (In a side note, Isaacson mentions he forfeited his original copy of Hear, O Israel:“I lent it to Jerry Richardson when he was playing on one of my soundtrack recordings in the mid-1970s, and he never gave it back to me!”)

The studio do-over could have stood on its own, but sometime later Klein felt a few bits of the original would fit well as segues and intros for the reprise recording. “The Union of Reformed Judaism said we could use about five minutes from the 1968 album without paying licensing fees,” he said. “That was plenty to work with, since the parts I thought worth preserving were some of the trio portions with Herbie, Ron, and Grady Tate. We selected four excerpts and wove them in to complete the recording.” Even for the untrained ear, it’s not hard to detect just where those parts come in—check out opening bars of the “Sh’Ma,” “Mi Khamokha,” and the finger-popping “Torah Service,” as well as the piano solo in “Adoration” to hear Hancock’s unmistakable contributions to the Milken Archive, alongside the Jonathan Klein Jazz Ensemble.

Klein never doubted the superiority of the new version. “Everything clicked—the caliber of the players and their interplay with the singers, the pacing, even the keys we chose. And Herb Pomeroy’s performance—every note was perfect,” he said. “I could finally stand to listen to it.”

***

I knew from previous attempts to speak with Herbie Hancock about the Israel recording that he had limited memory of the project. Or did he? I began to wonder after receiving a photo Rabbi Davis sent me—a copy of the reissued Trunk CD with a bold greeting autographed across the plastic cover: “Happy Birthday Rab!! Herbie Hancock.” It seemed that Herbie’s “secret album” may not have been so forgotten after all.

Thus, after many weeks of trying to make contact, I was happily surprised to get a call one afternoon in mid-February from Herbie’s daughter Jessica, asking if I still wanted to speak with her dad. Of course, I do! She cautioned he might not have much to share about the recording—it’s been so long, and other people have asked, to no avail.

“Well, I never forgot I did the album—even if I don’t recall a lot about the session itself,” Hancock explained from his office in Hollywood. “I was just doing so much during that period, living in New York, working every day, every week. It was a very important time for me because I was still associated with Miles but also exposed to so many new influences and getting ready to go off on my own. I know the record was for a limited audience, so I never really had a chance to take it in after we made it.” As he talked, more lights began to turn on.

“I remember the composer was a young guy, and this was his first time in the studio—and he was very sincere about his work, which included these wonderful opera singers and speaking parts in Hebrew. It was definitely the first and probably only time I ever did a record with a rabbi!” He laughed at the thought. In a few years Hancock would form a lifelong connection to Buddhist chanting, but even at 27, he said, “I felt I was already becoming a spiritual person, and here was this music that was connected to the Jewish faith, and I hadn’t experienced anything like that before.

“So even though it may have seemed like a one-off job, I could tell that the work was coming from this young composer’s heart and wasn’t just another thing to do like many other albums we had lined up back then,” he continued. “And I felt it would be a good thing to expose myself to something I wasn’t familiar with—that’s the only way you can grow as a musician and as a person. I know we were squeezed for time, but I was happy to accommodate this project because it was so different and had a spiritual component. Exploring his music, even for just that one day, I’m sure gave me a slight leg up for the next thing.” Indeed, he agreed it could well have carried over to what he was about to do so soon afterward on Speak Like a Child. Hancock figures he made a couple of hundred dollars from his effort that December day, unaware of the dividends his performance created for others in years to come.

When I told him that Klein was displeased with the record and its mistakes, Herbie asked how old Klein is now. “Wow, he’s almost 70?” asked the pianist, who himself will turn 78 in April and is wrapping a new album, his first in eight years. “Tell Jonathan I said hi, and that maybe he’d want to go back and listen to it once more, with old ears. Sometimes the best parts are in the mistakes. He may feel better about it now.”

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Allan Ripp runs Ripp Media, a press relations firm in New York City.