The God of Manga’s Jewish Masterpieces

On Osamu Tezuka’s 88th birthday, a look at the many ways the Japanese master told Jewish stories, and influenced the Jewish storytellers of America’s own comics boom

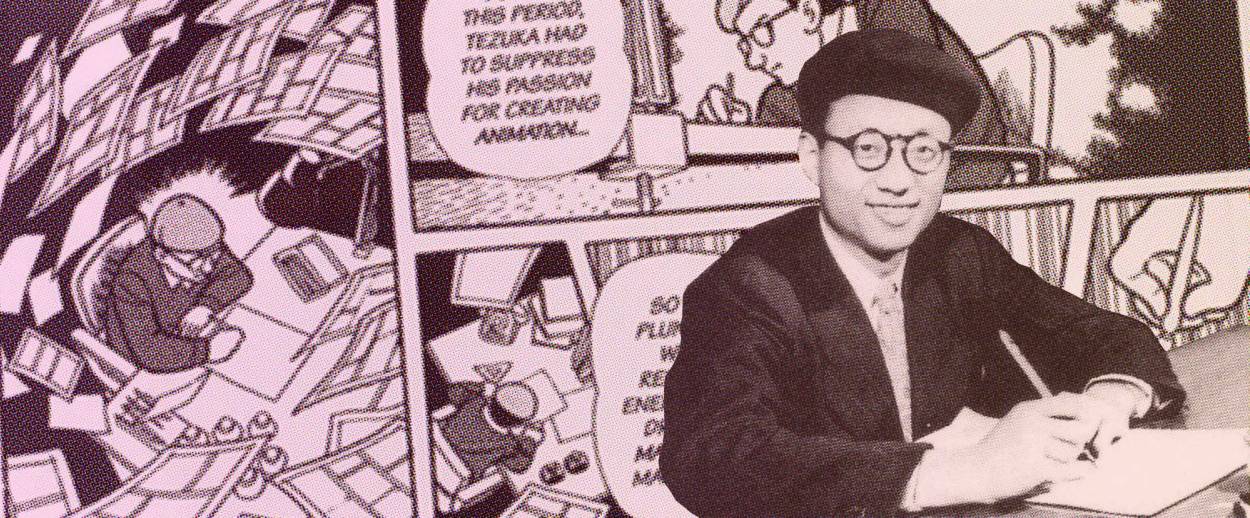

The mammoth 928-page volume of The Osamu Tezuka Story: A Life in Manga and Anime (recently published in English by Stone Bridge Press), opens with a provocative question: How have manga—Japanese comics—become an integral part of Japanese society, read practically anywhere, by all age groups, and touching every imaginable subject and genre, when, despite their global fame, American comics never reached the same cultural magnitude even in their own country? The answer that the book offers is simple: American comics never had Osamu Tezuka.

To be sure, it’s not just a simple, but also a simplistic explanation (mainstream manga never had to endure anything similar to the Comics Code Authority that American comics had to endure for decades, for example). Yet it is true that the uniqueness of Japanese comics culture is strongly tied to the uniqueness of Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989), widely known as Japan’s “God of Manga.” The title itself implies this uniqueness—do we have a “god of comics” in America? How about France? In Belgium, the legendary Georges Remi, better known as Hergé, can be said to hold a cultural significance that is somewhat similar to that of Tezuka in his native country, but Hergé is almost exclusively associated with a single title—The Adventures of Tintin—whereas Tezuka has created dozens of iconic characters that became a part of Japan’s popular culture, in an output that’s estimated to be 150,000 pages that he drew in his rather short lifetime. Tezuka found time for other things as well: He graduated from medical school and was licensed to practice as a doctor; produced hundreds of hours of animation in both films and television shows, putting Japan on the global animation map and making animation one of his country’s leading cultural exports; published weekly film reviews; and appeared in television advertisements. Tezuka was also an obsessive reader, and his vast knowledge of literature, history, science, and philosophy often echoes in his artworks. This intellectual quality takes Tezuka’s global influence deeper than that of most of his Japanese colleagues’: The most famous case of such influence may be the inspiration that his animal adventure series Jungle Emperor Leo (known in English as Kimba the White Lion) provided for the Disney hit film The Lion King.

With the rise in popularity of manga among Western readers, the 21st century saw a surge of interest in Tezuka in the English-speaking world. Not only were readers treated with many translations of his works, but scholarly studies of these works also began to appear: Frederik L. Schodt’s The Astro Boy Essays (2007) traces the history and cultural influence of one of Tezuka’s most beloved heroes; Helen McCarthy’s The Art of Osamu Tezuka: God of Manga (2009) is a lavishly illustrated coffee-table guide to Tezuka’s works; and Natsu Onoda Power’s God of Comics: Osamu Tezuka and the Creation of Post-World War II Manga (2009) is a study of the influence of stage-theater on Tezuka’s style.

The Osamu Tezuka Story: A Life in Manga and Anime, which now joins that list, is something of a different animal. Written and illustrated by Toshio Ban, who worked as one of Tezuka’s chief assistants, the book is a biography of Tezuka in a graphic-novel format. It tells the story of Tezuka’s life, from his birth through his adolescent years in the shadow of World War II to his great postwar success up to his death. Though I am sure most of the book’s potential readers are already familiar with his biography, Ban’s book tells it in an unparalleled detail, both visually and narratively. Interestingly enough, the book keeps a constant low-key tone, even when approaching the different personal and artistic conflicts that Tezuka has encountered throughout his career. But there is something misleading in the book’s subtitle: A Life in Manga and Anime is definitely more about Tezuka’s life and less about his comics or animation. The book is mostly about the many twists and turns in Tezuka’s career as a comics artist and animation producer (devoting a lot of space to the great suffering publishers had to endure while waiting for Tezuka to deliver his weekly pages), with occasional brief discussions about the content and the style of his works.

Yet even in these brief discussions, readers can find surprising links that lead from Tezuka’s works to Jewish culture and history. In his youth, when Tezuka began shaping his personal style of drawing and storytelling, introducing traits that accompany the mainstream manga industry to this very day (characters with large round eyes, cinematic page layouts, and frequent use of silent pages with no text), he drew influence from fellow Japanese artists along foreign sources of inspiration, most notably Disney. Often overlooked, however, is the equally important influence that Disney’s greatest rivals, the brothers Max and David Fleischer, had on Tezuka with their Betty Boop and Popeye the Sailor cartoons that reflected (and sometimes even directly referred to) their creators’ background as Jewish immigrants in urban America. Even less well-known (though nicely referred to in Ban’s book) is the important influence that Tezuka drew from Yiddish cartoonist Milt Gross and his silent graphic novel He Done Her Wrong, which also strongly reflected its author’s Jewish heritage.

Works drawn by Tezuka toward the later part of his career—decidedly darker and more pessimistic in comparison to his immediate postwar works—show an increasing interest in Jewish life and history, an interest that made it to the narrative of some of his most acclaimed works. His 1970 series Apollo’s Song is a grim tale of a violent young man forced to learn the meaning of love through living the different painful ordeals of tragic figures. One such figure is a Nazi officer who accompanies Jewish prisoners on a train to a death camp and falls in love with a Jewish girl during the journey. The portrayal of the Holocaust in the story feels more like a portrayal of abstract evil rather than concrete history, but another element of the story, the horror of war, feels very concrete and real.

As demonstrated in The Osamu Tezuka Story: A Life in Manga and Anime, Tezuka had plenty of personal experience to draw from when it came to the horrors of war, with his adolescent years dominated by the destruction brought by Allies’ bombings and the sight of dead bodies scattered in the streets becoming something of a daily routine. While some may find this connection troubling given the nature of Japan’s involvement in WWII, it appears that for Tezuka, the Holocaust and his own personal experience were symbolic of just how far human cruelty can reach.

A deeper understanding of Jewish history can be found at Dawn, the eighth volume of Tezuka’s epic Phoenix cycle of historical and futuristic stories that follow the human race’s destructive quest for immortality. Published in the mid-’70s, Dawn is a science-fiction tale of a woman named Romy who finds herself abandoned on a distant planet and eventually attempts to make her way back to Earth. During her journey, Romy compares herself to the Jews who were exiled from their homeland for thousands of years, yet never gave up the hope of returning to it, eventually doing so and re-establishing it as their national state. But just how fruitful is this process of return, given that both the Jewish people and the state of Israel (we are to assume) no longer exist as separate cultural/national categories in the distant future in which the story takes place—or, for that matter, that Romy’s own return to her home planet proves to be a tragic affair? While Tezuka does not give a direct answer to this question in Dawn, he does provide it in one of his final works, A Message to Adolf.

Serialized in the mid-1980s, A Message to Adolf is considered among the greatest masterpieces of not only Tezuka’s works but of Japanese and global comics as well. The series tells the story of people who share the same first name—Adolf Kamil, the son of a Jewish family that found refuge from Nazi Germany in the Japanese city of Kobe, and Adolf Kaufman, the son of a senior Nazi diplomat who lives in the same city. The story begins in the 1930s, as both protagonists become friends after being bullied by local Japanese children who treat them as dangerous foreigners. But their friendship turns into bitter hatred as greater events place them on the opposing sides of history over the course of six decades—from the deadly battlefields of Europe and Asia in WWII through the Holocaust all the way to Israeli-Arab conflict.

Although much wider in scope, A Message to Adolf places the Holocaust in the same context as Apollo’s Song did, that of WWII, hence sharing the weakness of the former work—treating a systematic form of mass-murder of innocent people as the ultimate manifestation of war, even a cruel one, rather than a unique affair. However, A Message to Adolf also extends the context significantly. If Apollo’s Song dealt with the horrors of war, A Message to Adolf claims that these horrors are rooted in a greater evil: nationalism.

Throughout the series, Tezuka draws parallels between the path that led from German nationalism to the crimes of Nazism and the Holocaust and those that led from Japanese nationalism to the crimes committed by Imperial Japan toward its own citizens and the people of Asia. It is here that Tezuka reveals his complex perspective of the Jews as people: He expresses his admiration for The Wandering Jew, who has no country, no army, and therefore does not declare war upon others. The very same argument used by anti-Semites about the lack of national roots among the Jews, an argument leading to suspicion toward their thriving in different countries and cultures, was seen by Tezuka as ideal existence, one that is not plagued by the same dangers that nationalism is bound to deteriorate into. When Kaufman offends a Jewish violinist on a death march, saying that all Jews are “cockroaches,” the violinist responds:

What is it that you “humans” hate so much about cockroaches? … No other species seem to mind them the way you do. And besides, cockroaches will inherit the Earth long after your so-called human race is extinguished.

With this, Tezuka has brilliantly turned an anti-Semitic insult on its head: the ability of cockroaches to survive under the harshest circumstances is not unlike that of the Jews. The fact remains that the stateless Jews have managed to survive and maintain their own identity while established nation-states have crumbled to ashes.

This deep ambivalence finds its ultimate expression in the concluding chapters of A Message to Adolf, in which Tezuka mourns the fact that the Jews have embraced the same nationalism by creating their own state. Yet I would hesitate to label Tezuka as an anti-Zionist, at least not in the way the term is widely perceived today; Palestinian national inspirations are harshly criticized in the series as well. Tetzuka summarizes the Israeli-Arab conflict in this painfully accurate description: “The Jews fought to protect their new homeland, and the Arabs fought to drive out their Jewish enemies. Each people upheld their own concept of justice.”

The Israeli-Arab conflict was, for Tezuka, a manifestation of the never-ending tragedy of national conflicts and national states.

Of course, Tezuka could express this worldview from a comfortable position: His own country, in which he was born and lived throughout his entire life, had to give up its military aspirations following WWII, but not its national identity; like most Japanese, he never experienced the hardships of immigration, certainly not of the kind endured by people who had no homeland of their own to go back to. Nonetheless, A Message to Adolf remains a deep exploration of the meaning of the Holocaust and Jewish culture, which in the field of comics is second only to Art Spiegelman’s Maus.

Apollo’s Song and A Message to Adolf demonstrate the depth that Tezuka has brought not only to Japanese comics but to the art of comics as a whole, and they do this far better than the flattering portrayal of the artist in The Osamu Tezuka Story: A Life in Manga and Anime. Nonetheless, Ban’s book provides an interesting detailed look into Tezuka’s own life story, and many episodes in this story go a long way in explaining why he was attracted to Jewish history and culture.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Raz Greenberg, an animation researcher, is the author of Hayao Miyazaki: Exploring the Early Work of Japan’s Greatest Animator.