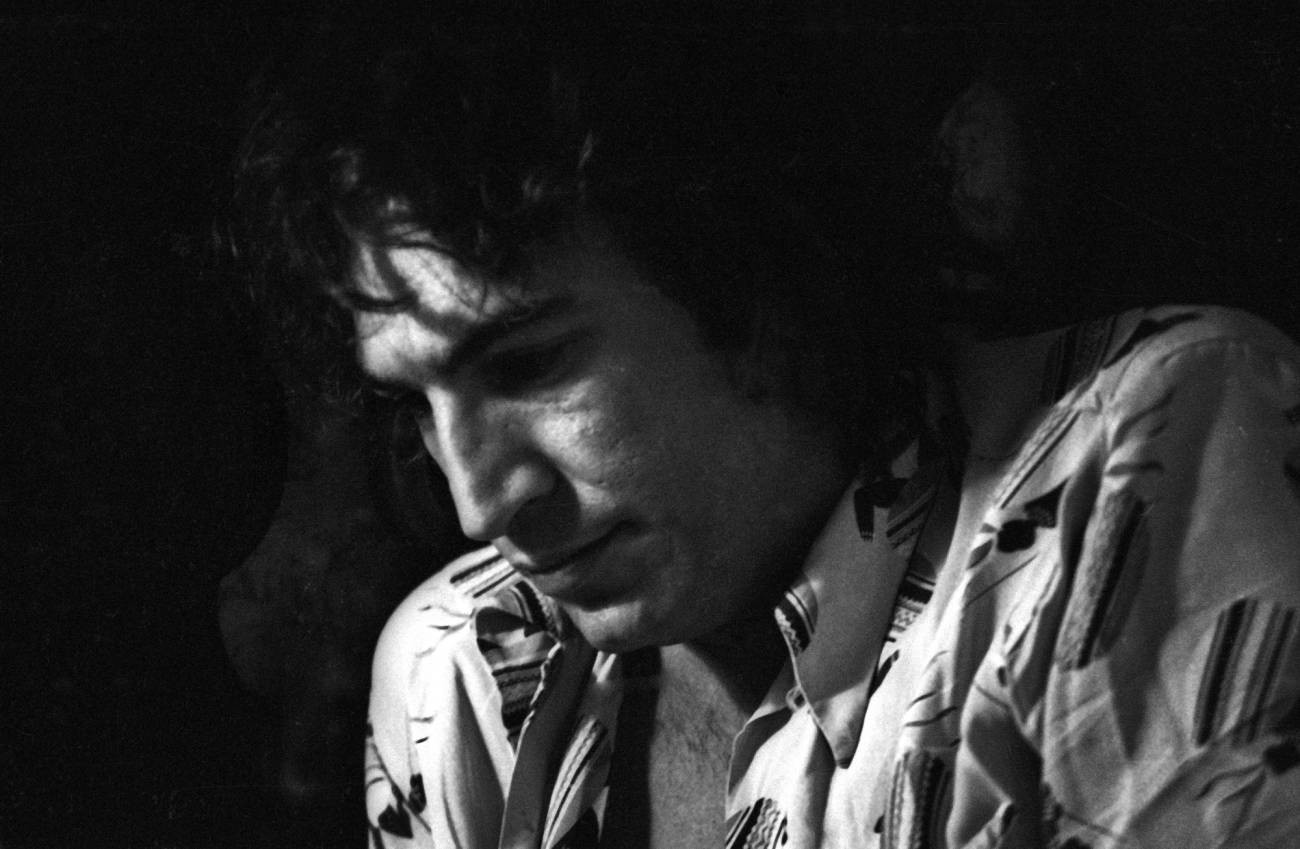

Record Master Marshall Chess

The record industry dynast talks music, family, and doing drugs with the Rolling Stones

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The Rolling Stones named themselves after a Muddy Waters song recorded at Chicago’s Chess Records, the eponymous label started by Leonard and Phil Chess. Leonard’s son Marshall was next in line, the heir apparent to a business famous for its roster of jazz and blues legends like Bo Diddley, Howlin’ Wolf, Chuck Berry, and Etta James. As a kid, Marshall would rock himself to sleep on the studio floor listening to their latest tunes. The Flamingos performed at his bar mitzvah, a rare integrated affair written up in Billboard and Cashbox. It was attended by friends from the the immigrant Polish Jewish synagogue; music legends Sam Phillips, Ahmet Ertegun, and Jerry Wexler; local pols; and friends among the invigorated Black population swelling with new arrivals from the South. While still in his teens, he’d ride in his father’s Cadillac learning the ropes and meeting DJs and record store owners.

His first official job at the label was to oversee the label’s expansion overseas. So when, in 1964, the Rolling Stones’ manager called to ask about recording in the Chess studio, Marshall agreed, even though his father looked down on the long-haired “homos” from London. Now 22 and hip to the significance of the Chess catalog to blues-obsessed Brits like John Mayall, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, and, of course, the Stones, he jumped at the chance.

If Chess Records was going to keep up with the changing times, it would be thanks to Marshall. He saw that there was a new market: teens in cars with radios, who craved more of the new and less of their parents’ music. These cheeky white Brits, he hoped, would help the floundering blues label appeal to younger listeners. The Stones’ first pilgrimage, in 1964, to the hallowed halls of 2120 S. Michigan Avenue—the title of an instrumental the band recorded at the studio during their visit—was a dream come true for the band, a chance to commune with the blues masters whose sounds were embedded in their musical DNA. To the Stones, Marshall was royalty, a made man. “They would kiss my balls to be on Chess Records,” he says. “You have no idea. For these guys being around me was like if you were a Ford car dealer and my name was Ford.”

Some 60 years later, Marshall lives in upstate New York, in a wooded compound where he likes to start his day on a stone bench facing a stream where he meditates and smokes his medicine. There’s a guest house, the main house, and acres of forest where his wife, kids, grandkids and dog like to roam. We meet in his office, where he maintains the archives that span a century of American musical history. And that history isn’t over yet. In 1997, Marshall and his son Jamar formed CZYZ Records, a nod to the family’s Polish name before it was changed to Chess. The label’s latest release is New Moves, a compilation of modern interpretations of blues songs from the ’50s and ’60s as well as a couple of new tracks. It was recorded by The Chess Project, a supergroup of hip-hop and rock ’n’ roll veterans led by Keith LeBlanc, once the drummer for Sugar Hill Records’ house band, and Bernard Fowler, a touring vocalist for the Rolling Stones.

Chess, who is still recovering from two spinal surgeries, may have slowed down physically, but his stream-of-consciousness conversation is as energetic as ever. Though the history of Chess Records is well-documented—including in Cadillac Records, a 2008 biopic featuring Adrien Brody as Leonard Chess—Marshall’s story is not as well known, which is something that he’s decided to change. “I’ve never tried to sell myself as this character, but now I’m 81, fuck it, you know, I’m gonna go for it,” he tells me. “I’m doing it to promote this album, you know, I’m still a record man. I still want to get a hit, unfortunately. Like the racehorse trainer wants to win the race.”

Though we’ve been acquainted for several years—I live in the same area, and we’ve met at barbecues hosted by neighbors—it’s only now that he’s expressed any interest in telling his story. In fact, he’s written a cheat sheet of his “Experiences/Highlights” that begins with “Born 3/13/1942” and ends with “Palenque Ethnobotany Week with Terence McKenna & the Shulgins (MDMA, Tryptamines) 1996?”

The music business was not in the cards when the Chess brothers—Leonard and his brother Phil—first opened a liquor store on Chicago’s South Side in 1942. That was followed a year later by the Macamba Lounge, an afterhours club in a predominately Black neighborhood patronized by musicians, prostitutes, and drug dealers. Impressed by the musical talent around them, the brothers invested in a local record label, Aristocrat, which they renamed Chess Records in 1950. Leonard may have lacked musical acumen, but he did know enough to convince Chuck Berry to change a song he’d titled “Ida Red’’ to “Maybelline,” a classic that’s hard to imagine by any other name 68 years later.

As an independent label, or “indie,” serving “race music,” as it was then called, Chess Records prospered. It attained the status of major indie, secure in its niche until the mid-’60s, when the British Invasion, civil rights marches, antiwar protests, and the rise of the counterculture upended its business model. By that time, Chess Records had grown into an institution, complete with offices, a recording studio, record pressing facilities, and a radio station. Such was the label’s stature, Marshall tells me, that Chicago Mayor Richard Daley once called Leonard for help quelling the civil rights demonstrations, telling him, “Leonard, the n*****s are on the warpath. Can you help me?”

Being young and hip, Marshall traded in his suits and ties for jeans, a mustache, long hair, and an apartment in Old Town, Chicago’s hippie neighborhood. Feeling the shifting winds, Marshall launched the Cadet Concepts label in 1967 with The Rotary Connection, an interracial psychedelic group backed on its first LP by a 20-piece orchestra. Marshall convinced Muddy Waters in 1968 to record an album that fused classic Chicago blues with ’60s psychedelic rock. Although critics panned it, Electric Mud was Waters’ first record to break into the Billboard 200, and it went on to attract a cult following among hip-hop musicians such as Chuck D. Marshall was off and running.

That is, until … “I got a phone call from this fucking phone [Leonard] had in his car. ‘Your uncle and I decided to sell. Don’t worry, you’re gonna get enough money to do your own thing.’ I was supposed to get a million bucks. And then, [in October 1969], my dad died at 52.” The new owner, the GRT tape company, was looking to expand into the music business. “They made me co-president and announced: ‘We’re moving to New York and we’re sending you to the American Management School because you have to learn how to forecast; we’re a public company.’” After three months, he quit. “I hated it. They couldn’t understand what they bought. It was the creativity, not a fuckin’ balance sheet with how many albums you sold. The worst part was my dad died and he didn’t leave a will. And I didn’t get my million bucks.”

As luck would have it, however, in 1970 Marshall learned that the Rolling Stones were dropping their label and looking for a new manager. Out of work and out of money, he called Mick Jagger: “I said, ‘look, my dad died. I quit. I have nothing to do. And I hear you’re looking for a new label and a new manager. There’s something we could do together.’”

“Oh, Marshall, that’s wonderful,” Chess says, mimicking Mick’s accent. Chess told him to come to Chicago. Mick couldn’t. “I just got my passport held. They found amphetamines coming into the airport in London. Until it’s straightened out I can’t leave. You come to London.”

At Mick’s London townhouse, Marshall was blown away by the opulence and sophistication of the fancy old building facing the Thames River at 601 Cheney Walk. “I’m a Jew from Chicago,” says Marshall. “This guy had Oriental rugs, sculpture, antiques, art work, and a giant pile of records lying about out of their sleeves. And he puts on this zydeco record, “Black Snake Blues” by Clifton Chenier. I’d recorded Chenier … Anyway, he started dancing and we had this great talk and he said, ‘Well, we’re rehearsing tonight. Come with us and meet everyone.’”

Upon entering the studio, Marshall saw the Electric Mud album cover “nailed to the fuckin’ post. I had Muddy Waters do one of their songs, ‘Let’s Spend the Night Together’ and they just loved that.”

So Marshall pitched the Stones. “I lied to them. I had no money. I was in deep shit. I said, ‘Look, man, I can’t wait around. I would love to do something with you. We can start a label.’ I said, we’ll have a logo and you’ll control everything. And I lied, I said I have some rich Texans who are gonna finance a label.”

They bought it. Marshall was named president of Rolling Stones Records in 1970, setting him off in a whole new direction. The hit records kept coming, as did a growing heroin addiction he picked up along the way.

He traces the addiction to the Rolling Stones’ U.S. tour in 1972, the band’s first since 1969, when they’d played a disastrous free concert at Altamont Raceway in California, where a gun-wielding fan was stabbed to death by a security detail made up of Hells Angels. Jagger was afraid to return to America, having heard that there was a contract out on his life, and he wanted a doctor on the tour just in case. Marshall found a trauma specialist who seemed perfect, but he didn’t realize that this doctor had his own problems. At the urging of Keith, Marshall tried some of the synthetic opioid Demerol they’d obtained from the doctor, and soon he was hooked. “And then Keith and I became, you know, drug compadres. I lived in his house. His best friend was [avant-garde filmmaker] Kenneth Anger,” he says. “He was a spooky motherfucker.” He remembers Anger drawing pentangles on the floor, playing weird piano music and chanting devil shit. “He was scary, dark, dark, dark. I stayed away.”

Chicago Sun-Times Collection/Chicago History Museum/Getty Images

For the ’72 tour, interest in the Stones was at an all-time high, crossing over from the music press to the general public. Truman Capote was assigned to cover the tour for Rolling Stone; Terry Southern for Saturday Review; and Dick Cavett did an entire show on the tour following its conclusion at Madison Square Garden. Adding to the mayhem was the decision to make a documentary of the tour. Robert Frank’s book The Americans, written with Jack Kerouac, was much admired by Mick and Keith, who sent Marshall to find out if Frank would sign on as director. Meeting in Frank’s Bowery loft, Marshall and Frank bonded, comparing stories about growing up Jewish in Chicago and Zurich. “Did I ever tell you about the film he made of me having a temper tantrum? He changed my life because he knew I was a neurotic, fucked up Jewish kid like he had been. And he thought I was brilliant. This is what he told me. I had tremendous potential, but I was horribly egocentric and fucked up and he turned me on to the Amazon [Ayahuasca] and Allen Ginsberg.” The resulting film, Cocksucker Blues, never got an official release, though it’s screened occasionally at MoMA.

After seven years with the Stones, Marshall told me he’d had it with “the rock star ego drain.” He kicked heroin with the help of psychedelic therapy from “Harry the Shrink” and left Rolling Stones Records in 1977. Other adventures in the music business followed, including a stop in the 1980s at Sugar Hill Records, the first label to turn the world on to this new form of Black music called rap.

He summarizes the rest of his career in the note he prepared prior to our sit down.

CEO/Partner ARC Music—(Music Publisher)—1992-2010

KRS ONE-Marvel Comics (Break the Chain)—1994

Sirius Show Host—“Chess Records Hour, 2006-2008

Sold publishing company, ARC Music in 2010 To Fuji Japan—2010.

These days, Chess is occupied by, and preoccupied with, his health, plus his new record and preserving the legacy of Chess Records. An attempted collaboration with a writer on his memoirs didn’t pan out. Instead, he’s telling his story through music and clips posted on his Chess Records Tribute YouTube channel. The Chicago of his youth is gone, as are most of the legends of that era. For now, Marshall is the repository of that fabled time that began with his Grandpa Chess, a junk dealer who collected bottles from local speakeasies he then sold to bootlegger-in-chief Al Capone. Marshall’s parents celebrated Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Hanukkah, and Passover. In those days, Jews and Black Americans mixed easily on Maxwell Street, finding common ground with their shared outsider status. “He had no prejudice,” says Marshall about his father, who grew up among Black Americans and was often mistaken for one when he spoke on the phone, in part due to his liberal use of the word “motherfucker,” a habit shared by Marshall. “We gave all the water for the march on Selma. I was never called ‘dirty Jew’ by Blacks, but ‘n****r lover’ and ‘dirty Jew’ by whites in the South, yeah. Many times. I heard no Jew animosity until later,” when Black Power replaced integration. “When Jesse Jackson came it changed,” he says, recalling a time he and his white secretary were roughed up by some of Jackson’s people. “Jesse Jackson hated Jews, still does.”

Whatever disputes Chess artists had with the music business’s dubious accounting practices, they ultimately recognized the importance of the Chess family to getting their music out into the world. When Leonard Chess died, a long list of tributes came in to WVON (Voice of the Negro), the radio station the family ran, including from Muddy Waters and the state governor. More of a family than a business, the Chess home was open to all. Chuck Berry was a frequent guest and family friend. Marshall was his road manager and was asked by the family to speak at Berry’s funeral.

The recording bug—and the drive for those hits—is as strong as ever, but, alas, Marshall isn’t. “I have to learn to pace myself,” he says. “I still need woods time. I take naps because I don’t sleep at night.”

As I get ready to end our interview, he insists on taking me to the bathroom to see his sensory deprivation tank. Bad back willing, Marshall hopes he’ll soon be able to squeeze into the device that facilitates his meditation practice. He walks me to my car and invites me to return when his marijuana plants are fully grown. “Have you ever had trichomes blown up your nose?” he asks. I laugh. After nearly seven decades in the music business, Marshall still has rock ’n’ roll in his heart.

David Hershkovits is the founder and editor of Paper magazine.