Max Jacob and the Angel on the Wall

A new biography treats the anguished life of the writer and painter, who was so often overshadowed by accomplished friends like Pablo Picasso, with exemplary consideration

Max Jacob mainly persists on the periphery of the times in which he lived and the great men he befriended. The writer and painter, who was born in 1876 and died in the Drancy internment camp on the way to Auschwitz, lived during an enchanted era for French arts. Jacob, through his innumerable relationships, was at the heart of it. Though his most significant artistic contributions are likely his prose poems and experimental fiction, much of it still untranslated into English, Jacob is best remembered because of association with more celebrated artists, including poet and calligram maker Guillaume Apollinaire, multidisciplinary aesthete Jean Cocteau, and above all, his roommate Pablo Picasso.

In her new biography, the outcome of 30 years of research, poet and scholar Rosanna Warren shows great compassion for Jacob’s anguished life: a Jew whose conversion to Catholicism was never truly accepted; an adventure seeker whose embrace of a semimonastic lifestyle failed to quell the pull of the city and unrequited longing for younger men. Jacob’s restlessness was a testament to his ultimately impossible bid to “create a whole from multiple, contradictory parts.” Warren establishes a discrete narrative of his life through a meticulous account of Jacob’s day-to-day interactions and an attempt to place his artistic work more substantially alongside that of his peers.

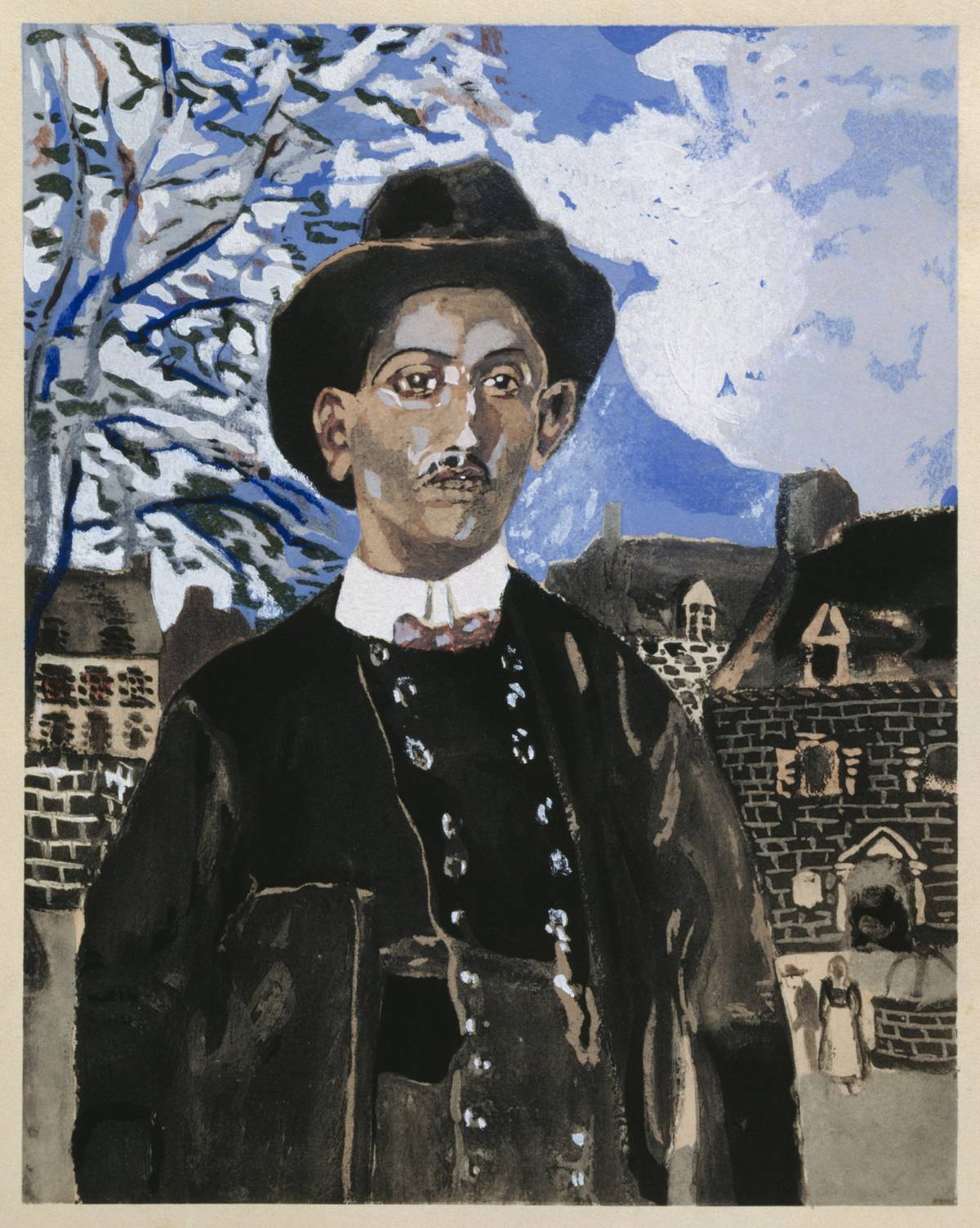

Jacob was born in Quimper, Brittany, in northwest France, in a “comfortable house on the quay of the Odet River.” He came from a nonobservant—in his word, “Voltairean”—household who listed their name as “Alexandre” and celebrated Christmas, in a secular way. Brittany was a “land of stubborn poverty, stony soil, Atlantic storms, and except in the larger towns, a peasant culture of primitive Roman Catholicism and lingering Royalist sympathies.”

Jacob would retain a connection to the aesthetics of the area: “granite chapels, ossuaries, and freestanding calvaires.” (Brittany would eventually provide him “with his own version of the Modernist primitivism that Picasso would seek in African and ancient Iberian sculpture.”) Though Jacob felt himself to be “thoroughly French” and his grandfather and parents were purveyors of Breton garb and furniture, living in the shadow of Quimper’s Gothic cathedral also entailed shocks of alienation. The family landlord, a local canon, told Jacob’s parents they were not welcome at a wedding service in the cathedral. At the local lycée, Jacob, known as le juif, was ignored or beaten by his peers.

It is Paris, not Brittany, that is the locus of this narrative. Warren documents the flows of human possibility that greeted Jacob when he arrived there aged 18: the sartorial extravagance and sensory juxtapositions, the whirl of origins and aspirations. Having been “versed in the myth of the conquest of Paris” through figures like Stendhal, Honoré Balzac, and Flaubert, Jacob entered “not so much a geographical area as a heavily charted literary terrain.” A sketch of him from this period by a sidewalk artist “portrays a young dandy in profile with a bowler hat, pince-nez, hint of mustache, starched shirt collar, cravat, and wide-lapeled jacket.” He was at the beginning of a search for his own mythology and Paris was the most fertile of locations for it.

When Jacob arrived in Paris, he was “too busy adjusting to his new life to concern himself with Jewish identity.” Yet the events of the 1890s would serve as his first reminder that Europe would concern itself with his Jewishness regardless of his own preferences and intentions. Newspapers like Édouard Drumont’s La Libre Parole reached a significant audience through brazen antisemitism. The Dreyfus affair placed the Jewish question at the center of a protracted and all-encompassing storm engulfing French political affairs and society. Mob assaults on Jewish shops across the country took place in 1898. “A crowd of peasants” attacked the Jacob family house in 1901, “blaming the town’s only Jews for the new anticlerical laws.”

Jacob was an apolitical man. He was equally unstirred by the rise of anarchism—which reached prominence through a series of bomb attacks in the 1890s and attracted support in particular from symbolist poets, a movement Jacob disliked—by Zionism, and by reactionary politics. His response to the grander tumult of his times was to “transpose those conflicts into aesthetic and erotic realms, choosing his own fields of battle and his own weapons, preferring privacy to politics.”

Warren’s book frequently brings to mind The Banquet Years, Roger Shattuck’s study of the French avant-garde in the late 19th and early 20th century. Looking to burrow into this resplendent era, Shattuck alternates between chapters on playwright Alfred Jarry, composer Erik Satie, painter Henri Rousseau, and Apollinaire, seeking the precise textures of how these artists and their wider circles transgressed aesthetic and social conventions and transformed their world into a “lusty banquet of the arts.”

The interactions that Shattuck and Warren both document—in salons, cafés, gardens and maisons de passe alike—are pregnant with audacious visions. As Shattuck writes of his artists: “Their lives matched their art in a way that does not even now seem natural. Their ‘act,’ an intensification of the exuberant play-acting of la belle époque, generated the energy necessary to change the direction of things.”

The commitment of these figures to art was fanatical, yet their perspective and tone was ironic—an alien combination today, when fanaticism and irony have cemented an antithetical relation. Shattuck sets the scene thus: “Now figures as heterogeneous as Max Jacob and Picasso and Modigliani worked in concert as if the world around them were the gala start of a voyage of discovery. They made fools of themselves and broached the limits of art.”

Warren’s book extends beyond the central cast of the avant-garde to encompass chancers, vagrants, groupies, and social climbers. In Jacob’s story, all the splendor and shabbiness, as Oscar Wilde put it, of Parisian life is on display, as is a shared hunger to harvest vitality from the experience of the city. An average page of this book is likely to find Jacob broke, painting gouaches to fund his writing, and chasing fresh dreams through trails of letters.

Jacob met the younger Picasso just after the Spanish painter came to Paris in 1901, and they soon became inseparable. Jacob was Picasso’s most significant initial guide into French society and language. They end up rooming together during a period of destitution and frenzied painting on Picasso’s part. Jacob later explained to the journal Cahiers d’art why he wrote poetry: “Picasso found I had talent, and I believed in him more than in myself.”

Picasso looms over the budding artistic schools of Warren’s Paris. The constellation of artists that soon forms around the painter—the so-called bande à Picasso—was marked by “stylish nonconformity,” “delight in disorder,” and an “expression of irreverence for any code outside its own.” Outside famous Montmartre haunt Lapin Agile, Picasso fires a pistol into the air to ward off some visiting Germans who wanted him to “explain his aesthetics.” Jacob contributes to the freewheeling gatherings of the bande by singing and clowning around, displaying the love of comic opera inherited originally from his mother.

The bande, however, was as “tightly knit by aesthetic purpose as by fraternal envy and aggression.” Jacob, whose “friendships followed a rhythm of complaint, offense, and agonized reparation,” was bruised by his search for warmth in this rivalrous, complicated and unpredictable clique.

Warren makes a case for Picasso and Jacob’s friendship having a dimension of mutual inspiration, certainly at the beginning. Yet their circumstances diverge radically across the book, as Picasso’s star continues to rise. The discrepancy in terms of success, social access, and the nature of their romantic relationships only grew wider over time.

Jacob felt the loss of those early intimate days of equal-footing and inter-dependence acutely. Yet he was so sensitive to Picasso’s presence that, for example, when the painter reaches a period without female support and wants to rekindle his bachelor days by moving in with Jacob, he refuses, finding the painter’s influence too great and the prospect of eventually being side-lined for another woman too painful. When the Gestapo finally came to arrest Jacob, he was working on a portrait of Picasso.

Apollinaire is a key figure in relation to both Picasso and Jacob. He was as famous for dismantling formal boundaries and received ideas in his own work as he was through daring public representations of the aesthetic revolutions. His punctuation-free poem “Zone,” which moves between the first and second person, is a tour of dislocation, juxtaposing with abrupt force modern Europe and its classical and Christian heritage. Apollinaire and Jacob shared certain technical affinities: They were “both excited by the new technologies of communication as metaphors for a poetics of immediacy,” and both attempt to incorporate fragments of the world around them directly into their work. Yet Apollinaire became a leading figure in a way that the more oblique, equivocal Jacob did not. His responses to Jacob included both praise and mockery.

It was an era of formal cross-pollination. Jacob’s 1911 text Saint Matorel appeared with Picasso illustrations. Jacob’s texts were set to music by Francis Poulenc and Satie, while some of his own poems, influenced both by phonetics and song, have a dittylike quality. Jacob’s “deliberately marginal poetry” involved “[cutting] his art down to essences of sight and sound.” Both Jacob and Apollinaire were fascinated and influenced by film.

Warren is thoughtful in linking Jacob’s artistry to his outsider condition as Jew, homosexual, occultist, and clown: “He was as fascinated by codes of social order and their enforcement as he was by codes of prosody, and he would acknowledge and subtly undermine these structures of authority all his life.” The prose poem, a testament to Jacob’s “lucid manipulation of the absurd,” is his quintessential form: of The Dice Cup (1917), Warren describes the “deep coherence undergirding its superficial disorder.” Cinématoma (1920), a series of “voice-portraits,” reveals Jacob as “an ethnographer of minutely recorded hierarchies.” Warren reveals how Jacob’s wordplay, in both private letters and artistic texts, contained deft routes of escape from social confinements: “Mad humor and cockeyed puns may be a version of going one better than assimilation: it was a form of seizing the controls.”

Jacob began having visions of Christ (one appeared on the wall of his room, another was projected on a movie screen), and converted to Catholicism in 1915, “renouncing the blindness of the Jews” on his baptism certificate. From 1921 to 1928, Jacob lived as an oblate in Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, central France, in a suitably incongruous relationship to the Benedictine monastery there: partaking in church services and other activities while not committing properly to the cloistered life, and often veering back into adventure.

Jacob was desperately earnest in his tergiversations. His problem was that the world only provided fleeting correlatives to what was inside his heart and mind. His conversion was a bid for acceptance—and yet it did not erase Jacob’s sense of his Jewishness, discipline or dogmatize his thinking, or smooth out his contradictory conduct. Even on the first day of instruction, his multifarious mind was on display: He scrambled to cover a statement entertaining the possibility of polytheism by saying he was referring to “Jesus, the Virgin, and the saints.” His esoteric and “zodiacal interpretations of New Testament tales” didn’t go down well, either.

Jacob remained aware, since he was so often reminded of the limits of protection offered by conversion within French society. “There’s no such thing as a disguise,” he disclosed in correspondence with a younger cousin, an aspiring writer: “Though a Christian can strengthen his spirit by trying to be Jewish, just let a Jew try the reverse: the critics will be sure to judge him irredeemably Jewish.”

As Warren makes clear, Jacob does not become ideologically anti-Jewish after his conversion. Yet one manifestation of Jacob’s Catholicism was routine proselytization. Warren sketches Jacob’s meeting with the novelist Albert Cohen, who had just published a poem by Jacob in his magazine in which “Jacob asserted the Christian revelation as a supersession of Judaism.” During the intense encounter, “each of these passionate men had in mind to convert the other”: Cohen criticized Jacob’s turn to Catholicism and urged him to embrace Zionism. Warren describes his encounter with Cohen as “tragically fruitless,” since Jacob’s attachment to Catholicism stopped him from being enriched by Cohen’s “intellectual and even mystical way of being Jewish that in no way resembled the commercial and academic worlds of his family.”

Jacob courted resolution of his internal conflicts, yet he wouldn’t have existed in the same way without them: He was his crisis. To quote literary scholar Judith Morganroth Schneider: “Contradiction determines the very structure of Jacob’s thought … The synthesis is always missing.” Warren argues, however, that Kabbalah functioned as a “model of synthesis” for Jacob, as well as a way for him to “preserve his Judaism.” His conversion did not dampen his attachment. He declared himself “deep down, very much a Kabbalist” in 1938, and in one of his final letters, he was advocating a “Kabbalistic” reading of that “Jewish book,” the Bible.

The playful nature of Jacob’s art didn’t change after conversion. He still made japery of his circumstances. He even “[experimented] ironically with blasphemy,” as in the case of “The Demoniac’s Mass,” which puns on an “astral orifice” to flip a vespers service hymn into “an astrological obscenity.” The Catholic printer refused to set it.

Though a Christian can strengthen his spirit by trying to be Jewish, just let a Jew try the reverse: the critics will be sure to judge him irredeemably Jewish.

Nor did a quasi-monastic life dampen the siren call of new connections. As the luminous legend of Paris—and Jacob’s set within it—spread, a stream of aspirants came into his orbit. Jacob returned to live in the city in 1928. His excruciating pursuit of a succession of younger men culminates in a self-debasing fixation with Maurice Sachs, a Jewish writer and arch social manipulator who converted to Catholicism under the guidance of Cocteau, his lover. Sachs ends up fleecing Jacob and others for cash and connections, leading a lavish life and “entertaining lovers like a pasha”. Sachs eventually mocked Jacob as a “lascivious hypocritical Jew” in a roman à clef.

Jacob’s relationship with his family—long exasperated by his impecunious, bohemian lifestyle—gradually worsens. His periodic returns to his family home in Quimper to focus or rest become less welcoming and more alienating: “The protectors of my childhood expected a scholar or an honest civil servant: I gave them some kind of ignorant artist. To the protectors of my youth who expected a painter, I gave a writer, and vice versa. To others, I gave nothing at all.”

While Catholicism entailed keeping up certain appearances—to which Jacob is committed, even if often clumsily or awkwardly—the more intense and uncertain politics become in French society, the more Jacob’s public stances affected his personal security. Jacob’s delicate temperament, combined with his many-guised existence within French society, generated many self-dramatizing moments. Cocteau asks Jacob to serve on a prize jury for the scandalous novel The Devil in the Flesh, written by Cocteau’s lover Raymond Radiguet. Jacob is anxious about what the church will think, given the book’s carnal content: “It’s very hard to do good, and to know on which side duty lies.” When the priests at Saint-Benoît pressured him into voting for the far-right Action Française in elections, he told Cocteau that he was being forced “to vote against [his] origins or against the Church.”

Toward the end of the narrative, the shielding utility of conversion crumbles altogether. Faced with the darkening atmosphere, Jacob sought a way out of imposed dichotomies: “We live in a partisan era, and I just want to die in God, that’s all.”

Marcel Jouhandeau, a repressed homosexual novelist who taught at a Catholic school, was one of Jacob’s most intimate correspondents. He published an article titled “How I Became an Anti-Semite” in 1936 that called for the mass expulsion of Jews from France. The piece provoked private, and defensively Jewish, responses from Jacob. In a letter to a friend, he wrote: “It’s we who invented the religion of suffering … Let’s learn to suffer with the grandeur implicit in the high destiny of our people.” Jouhandeau apologized in their final exchange of letters, just before Germany invaded France.

As the Holocaust comes into view, friendship and identity come into even sharper focus. “My friends are my native land,” Jacob tells a young Breton poet in 1942, part of a small circle who kept in touch with him during this period of deprivation and dread. In February 1944, Jacob was taken from Saint-Benoît, where he had returned in 1936, to Drancy.

Here, the most poignant contrast is between Cocteau and Picasso. Cocteau was friendly with Nazis, and kept working on his productions during the occupation of France. He spent evenings with the German ambassador to Vichy France, Otto Abetz; he was close to Arno Breker, Hitler’s favored sculptor. Yet Cocteau used his connections to try and save Jacob, dispatching a petition to the German Embassy, which included an encomium to Jacob’s talents and a reminder of his two decades spent as a Catholic.

Picasso, on the other hand, did nothing. After hearing of Jacob’s arrest, he said: “Max is an angel. He can fly over the wall himself.”

Warren, frustrated by the way this widely circulated anecdote dominates the memory of Jacob and taps into a one-dimensional image of Picasso, contextualizes things from Picasso’s perspective. Warren notes the painter was in a “lousy mood” when he produced the remark, which was broadly in line with the “cruel lingua franca of the Bateau Lavoir” (wash-house boat), the name Jacob coined for the ramshackle meeting place of Picasso’s set. She points out that Picasso originally offered to sign Cocteau’s appeal but was finally dissuaded from doing so. “As a resident alien in Vichy France”, he was justifiably worried by the “catastrophic” potential consequences of deportation to Franco’s Spain, and was advised that his signature would anyway “carry no weight with the Gestapo.” She does not seek to straightforwardly exonerate the painter, and earlier in the book labels his refusal to sign a “betrayal.” In a book full of feeling for Jacob’s marginality, Warren’s depiction of Picasso’s self-interested inaction only confirms the unequal nature of Jacob’s most important friendship.

Mardean Isaac is a writer and editor based in London. Educated at Cambridge and Oxford, he has written for publications including the Financial Times, Lapham’s Quarterly and New Lines magazine.