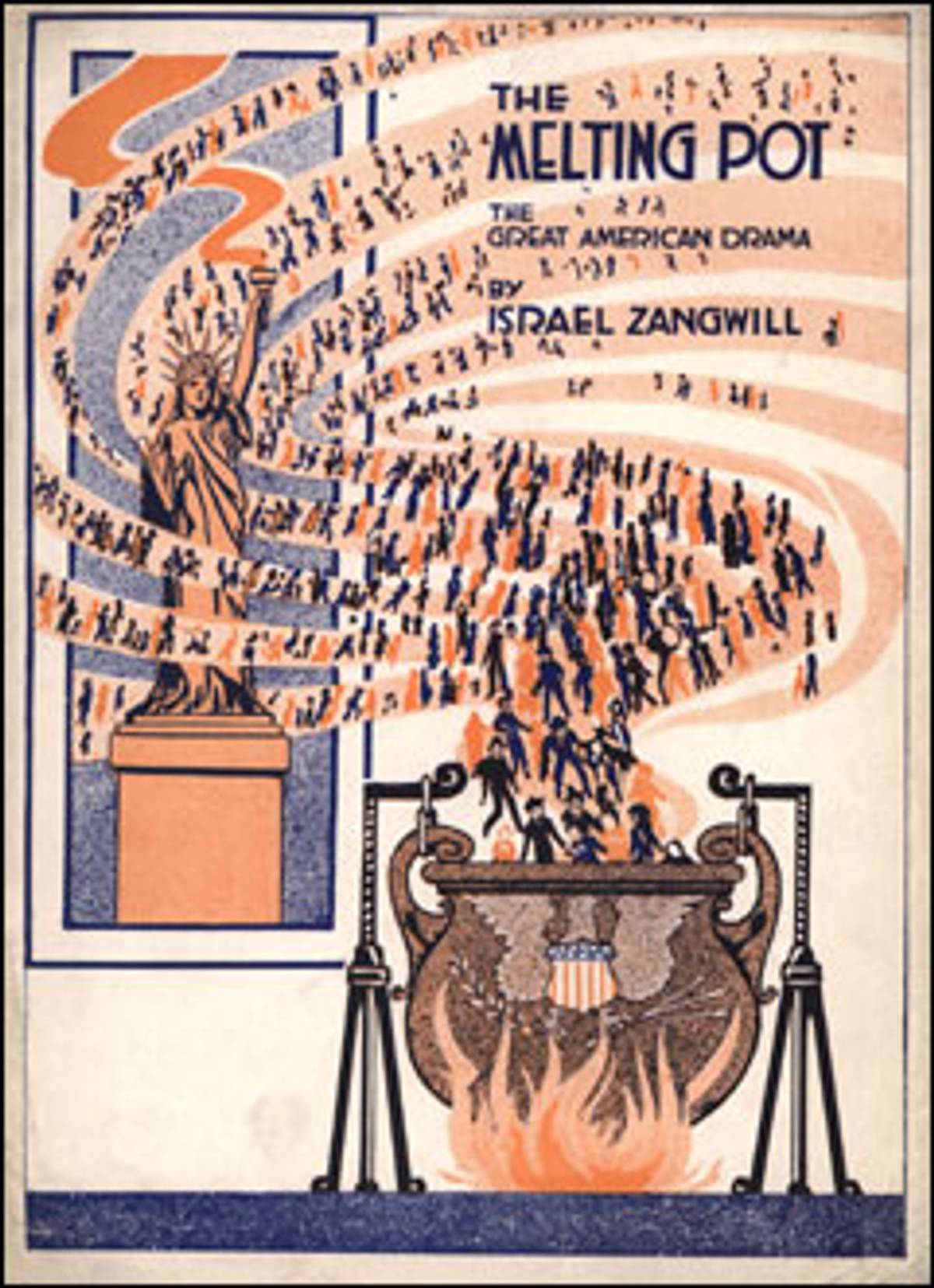

On October 5, 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt, the First Lady, and an entourage of dignitaries gathered at Washington. D.C.’s Columbia Theatre to catch The Melting Pot. Set in New York in the early 20th century, the play chronicled a tumultuous love affair between two Russian expats: Jewish composer David Quixano and Vera Revendal, an aristocratic ex-revolutionary. In a country that welcomed thousands of immigrants every day, the then-provocative title—with its vision of America as a bubbling cauldron of cultures—resonated deeply with theatergoers, including the President, who applauded loudly throughout, shouting, “It is a great play, Zangwill!”

If there was ever anyone capable of turning a metaphor into a household word, it was Israel Zangwill. From his impoverished roots in the East End of London, which in the late nineteenth century was home to multitudes of downtrodden Eastern European Jewish immigrants, he grew to become one of the most outspoken arbiters of the Jewish cause and famous men of letters of his day, counting H. G. Wells, Rudyard Kipling, and Arthur Conan Doyle among his friends and earning the admiration of American literary luminaries like William Dean Howells and Willa Cather.

Throughout his adult life, Zangwill’s portrait—receding chin, wavy dark hair, large eyes peering enigmatically from behind a sloping pince-nez—was a staple of major magazines and newspapers; in 1923, the Jewish Tribune had Zangwill third on its list of the “twelve outstanding Jews of the world,” after Albert Einstein and Chaim Weizmann. When the author gave a speech or published on any topic, his words sparked debate on both sides of the Atlantic. British society looked to him as the authoritative voice on all things Jewish. “Zangwill was the Elie Wiesel of his day,” said Edna Nahshon, the editor of a new volume of Zangwill’s plays, From the Ghetto to the Melting Pot.

Born in 1864, Zangwill attended the prestigious Jews’ Free School in Spitalfields. Lord Rothschild offered to be the precocious teen’s patron, but Zangwill didn’t want to feel beholden to a benefactor. At 18, Zangwill and fellow student-teacher Meyer Breslar published a novella called Motso Kleis (Matzo Balls), which vividly depicted market day on Petticoat Lane, complete with Yiddishisms and mispronounced English. Enraged and embarrassed, school authorities dismissed Breslar and ordered Zangwill to refrain from publishing.

It was another bare-all portrayal of lower-class Jewry that shot Zangwill to fame in 1892. Though many well-heeled American and British Jews objected to Children of the Ghetto, the novel was more than an instant hit. “It was an event,” Rabbi Stephen Wise later said. Zangwill contributed regularly to Jerome K. Jerome’s popular humor magazine The Idler and penned The Big Bow Mystery (1892), one of the earliest “locked room” crime novels. But his reputation lay mainly with his Jewish ghetto fictions, including the comic novella The King of Schnorrers (1893) and the haunting short-story collection Ghetto Tragedies (1893.)

A champion of liberal causes from the women’s movement to human rights, Zangwill gained the greatest fame as a spokesperson for Jewish emancipation. Following an 1895 meeting with Theodor Herzl, Zangwill became convinced of the urgent need to create a Jewish homeland in Palestine. In 1901 he joined the Zionist Federation, devoting himself and his pen entirely to the Zionist cause. Around the same time, Zangwill abandoned fiction for playwriting, composing original works but also adapting his novels for the stage. Zangwill felt that the theater—then a mass medium—provided the most effective mouthpiece for his polemical ideas. His 1899 stage version of Children of the Ghetto was the first mainstream play in English to move beyond the hook-nosed miscreant in dirty gabardine. And The Melting Pot, with its love affair between a Jew and a Christian, sparked energetic debate in the media about mixed marriage (Zangwill was married to Edith Ayrton, a non-Jewish writer and feminist) and launched a slew of imitations on Broadway, from Thomas Addison’s Meyer and Son to J. Hartley Manners’ The House Next Door.

While the melting pot has become a defining metaphor of American society, the play itself has not been revived professionally since 1926, the year of Zangwill’s death. The Metropolitan Playhouse, an Off-Off-Broadway company, is remounting it now in New York, but to read Zangwill’s plays today is to gain insight into the author’s present obscurity. As a novelist, Zangwill sought to entertain, though larger political motives underpinned his plots. In his plays, however, politics overtake plot. Despite brightly humorous moments, the dramatic versions of The Melting Pot and Children of the Ghetto are ham-fisted melodramas made worse by Zangwill’s didactic tone. In The Melting Pot, for instance, Quixano views America as “God’s crucible” and Americans as “the fusion of all races, perhaps the coming superman.”

Biographers tend to attribute the demise of his literary reputation to his move into social and political-themed dramas and essays. But his lifelong knack for controversy definitely had something to do with it. On his highly-anticipated first U.S. lecture tour in 1898, he dismissed most contemporary plays as crowd-pleasing fluff. This assault backfired: Zangwill’s dramas, no matter how well received on tour, were often critically panned in New York.

Meanwhile, his constantly swerving but always zealous perspective on Zionism earned him similar ire among Jews. In 1905, he broke with the Zionist movement and became involved with the Jewish Territorial Organization (ITO), an unpopular group pushing for a Jewish homeland outside Palestine. Following the Balfour declaration in 1917, Zangwill again called for the speedy establishment of a Jewish State and the transfer of Arabs out of Palestine. But in 1923, he declared political Zionism “dead,” which outraged English and American Jews.

Many Jews found fault with the union of the Jewish Quixano and the Christian Revendal in The Melting Pot. Zangwill, they determined, argued for the loss of Jewish identity in a homogenized American stew. In fact, Zangwill meant nothing of the sort. He was committed to building a Jewish homeland but also understood that Jews had come to a fork in the road: if full Jewish nationalism could not be achieved, full assimilation into a multi-ethnic melting pot was, for him, the next best thing.

In his 1926 book, The Jew in Drama, J.M. Landa derided Zangwill for his use of the stage as a pulpit. “If only he would drop the mantle of the prophet!” the exasperated critic declared. With cultural assimilation in many ways having proved itself more successful as a paradigm for society than hard-line nationalism over the last century, it seems Zangwill’s vision in The Melting Pot, though idealistic, may have not have been entirely in vain. Perhaps he was a prophet after all.