Blow Up the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe

What’s the right way to remember both victims and perpetrators of great crimes?

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is located in Berlin’s central government district, one of the city’s most popular tourist destinations. A short walk north is Brandenburg Gate, and beyond that the Reichstag. To the west is Tiergarten, Berlin’s largest park. To the east is a group of stores and restaurants catering to tourists, nicknamed “the Holocaust beach” by the German press. Nearby are three more memorials: the Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted Under Nazism; the Memorial to the Sinti and Roma Victims of National Socialism; and the Memorial and Information Centre for the Victims of the Nazi Euthanasia Programme.

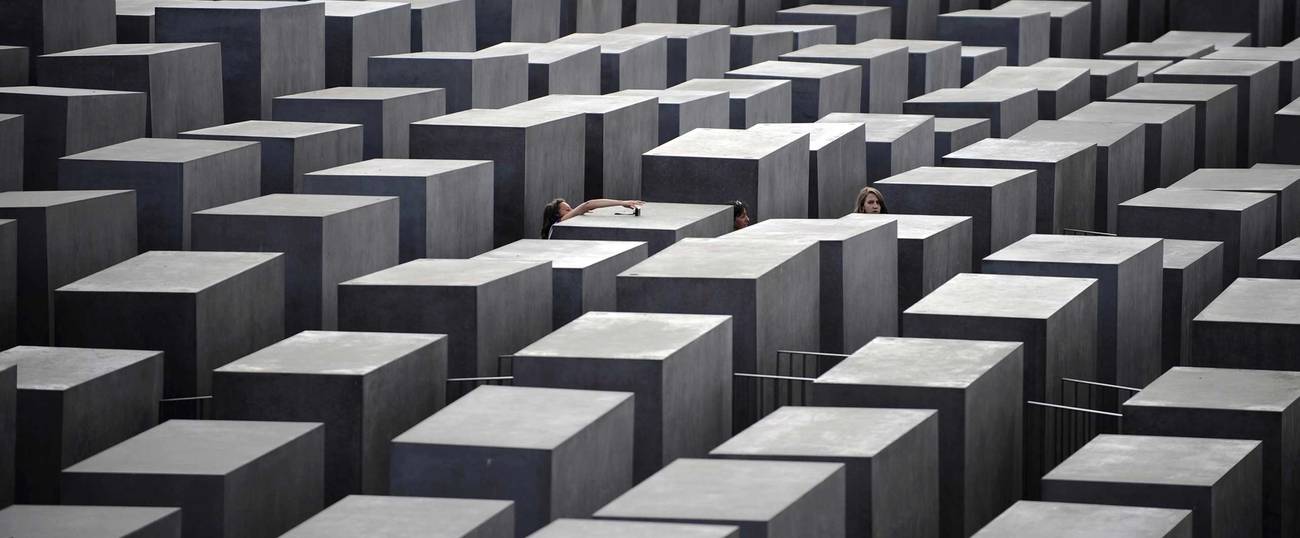

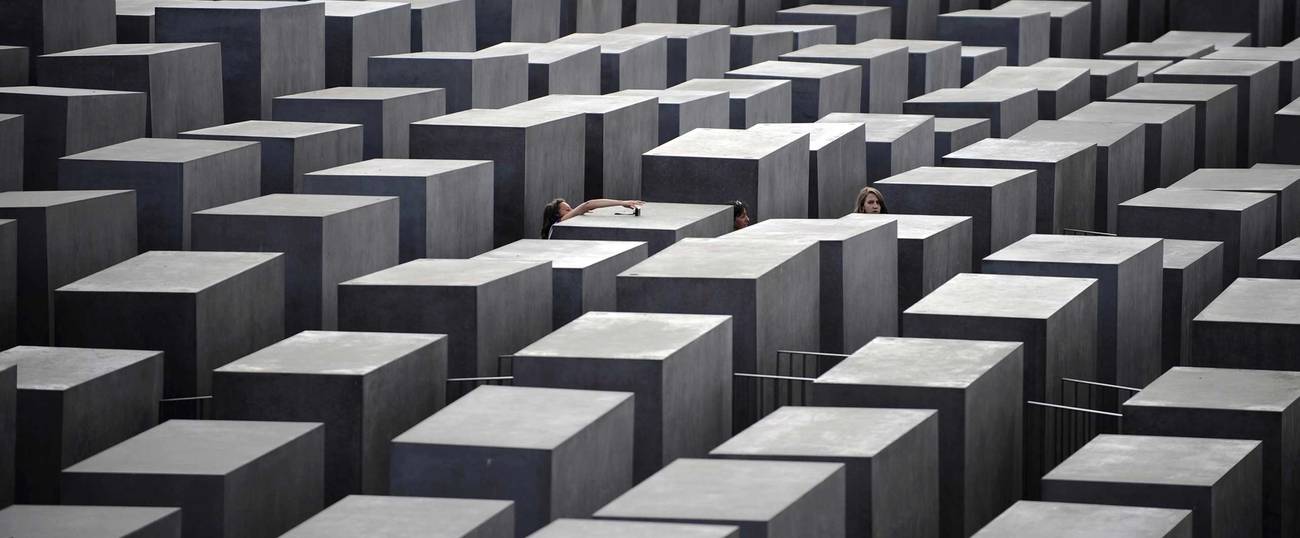

The main memorial was designed by the American architect Peter Eisenman. It consists of 2,711 stelae—rectangular, undifferentiated concrete slabs of monotonous gray with a smooth finish—arrayed in a grid across a sloping field. As visitors descend into the site, the stelae rise above them and their perspective becomes disoriented, fragmented; they can hear voices, sounds, laughter, but cannot locate the source; they pass blindly through the grid’s intersections, unsure what they will find around the corner. In its quieter, more contemplative moments, which are rare, it insinuates the atmosphere of a de Chirico painting. Eisenman insists that the design, including the number of stelae, has no manifest symbolism, “no goal, no end, no working one’s way in or out.”

Four million people visit the memorial every year. School groups, tour groups gather near the northwest corner of the memorial, the informal meeting point, the informal photo vista; visitors pull out their phones, unpack their cameras; students look bored; teenagers jump from stele to stele until a security guard, who has the thankless job of stopping visitors from climbing on a Holocaust memorial, tells them to get down; parents shepherd their kids through the family vacation; children play hide-and-seek, play tag, play games incomprehensible to adults; teenage boys chase teenage girls, eliciting shrieks; boyfriends disappear into the grid, reappear around a corner, eliciting shrieks; weekend jet-setters debate plans for the night, flirt in broken English; girls tan on the slabs with their shirts pulled up to expose more skin, a couple takes a sun nap; photos are staged, iterated, dissected, restaged: curl the hair over my ear, two steps to the left, readjust my bra strap: 87 likes.

One hears trampling feet; the ecstatic shrieks of children, teenage shrieks calling for attention; “We can do it on my phone too, once it’s charged”; photo appraisal; bags swinging; “It is kinda like a maze, yeah”; a man making fart noises; “Get Busy” by Sean Paul playing on portable speakers; “I only have an 8-gigabyte phone”; the thud as someone jumps from stele to stele above you; “Marco … POLO”; the click of a lens; “to play here at night—that would be awesome!”; a Babel of languages; “Is there a Starbucks?”; laughter that verges on tears, gasping laughter, panting laughter; “I would never go out with Crocs”; vroom vroom noises; a young American woman whose friend’s parents “only drive electric cars and stuff like that” informing her German counterpart, “If you have free college, who do you think will pay for it? The taxpayer”; the crisp percussion of a high five; “We are playing a game!”; a camera lens slapping a bulky thigh; “It’s very existential!”; filtered traffic, whistles, futile attempts to impose order.

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is a mediated experience; like the “most photographed barn in America,” if the barn commemorated the murder of 6 million people. Teachers use photo breaks as a reward for listening to lectures. (Nothing brings a group of teenagers to bay like a selfie stick.) Visitors arrive, take photos, take a little stroll, take some more photos and leave. Popular poses include: wedged body in between stelae; stacked bodies wedged in between stelae; solitary subject sitting on a stele, back to the camera, looking out on the monument—all those murdered Jews, so sad—in stilted reflection; the album cover, for groups of four to six, one on each stele, arms and expressions spread wide, intimating a moment of spontaneous excitement, photographed seven times. According to the Israeli sociologist Irit Dekel, who had studied the memorial, many visitors don’t even know they are at a Holocaust memorial, which is believable. It is, for them, an Event, spreading from Instagram to Instagram, an item on the itinerary, somewhere between currywurst and the East Side Gallery, tethered to intention by a geotag.

There is something disconcerting about the way it sucks you into its tableau, the way it draws you into the spectacle. You are constantly being photographed, wandering into others’ photos, or waiting for a group to finish their latest photo set. Sometimes there is a conciliatory smile, a flash of embarrassment, perhaps a small realization of the absurdity. You are especially a target of surreptitious photogs if you happen to be writing in a notebook, suggesting a rare character at the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe: a person deep in contemplation, a person actively involved in the creation of thought. I wrote, “I would not like that the somber cast of my face, my face buried in my notebook as I write these lines, would somehow accessorize this moment, enforce the expected impression that otherwise doesn’t exist.” I looked up: My photo was being taken.

Beneath the memorial is the Information Centre, a permanent exhibition about the extermination of European Jewry, intended to address and rectify criticisms of Peter Eisenman’s design. It consists of five main rooms. The first is a timeline, a rough chronology of events, replete with the sort of shocking and grotesque pictures that were once uniquely shocking and grotesque. Visitors take pictures of these pictures. The second room displays letters written during the war, individual voices bearing witness to a partial purview. The third room tells the story of Jewish families across the continent, using family photos and contextual information to trace the dreaded fate of its members. (Haredi Jews of Eastern Europe, one of the largest victim groups, are often minimized in educational and artistic representations of the Holocaust. To be accessible, the Holocaust must be universal. We need the victims to look like we like to see ourselves: cosmopolitan, well-dressed, middle-class, and secular. No one can imagine himself as a Haredi Jew except a Jew. To the extent that Haredim appear at all, it is frequently during a moment of humiliation: as German soldiers cut off their payot; that is, as they become secular.) In the fourth room, the names of all known victims are read in looping video reels, sometimes accompanied by a short obituary. The fifth room documents the geographic locations of the killings. If you have read more than one book about the Holocaust, none of the information in the exhibit will likely be new to you—other than, of course, the individual stories. But not everyone is going to read Hilberg’s The Destruction of the European Jews. This exhibition, along with Schindler’s List, and maybe a week or two of school lessons, represents the totality of Holocaust education that many people will ever receive. The Information Centre, which was not part of the memorial’s original design, draws about a half million visitors per year, 12.5 percent of the total visitors to the memorial.

The memorial and exhibition, and memorial culture more generally, foster identification with the victim. When I visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington as a teenager, they assigned each of us a Jew, our Jew, whose progress we would follow throughout the museum. At the end, it was revealed whether they had survived or died. This affinity is not controversial nor is it some great secret. We should honor the victims, celebrate their lives, give them a voice; this is why we read their names every year, to feel the syllables roll off our tongues, to let them ring in our ears: a life. This is conventional wisdom, and it is nearly impregnable to criticism. No one wants to be perceived as smudging, let alone profaning, the sacred altar of victimhood. There is nothing particularly objectionable in the idea ex situ. It is, however, frequently conveyed via a common sentiment: That could have been you—you could have been the victim. Or it tries to insinuate identification on the basis of shared humanity: They loved their families too! But it is based on a false premise. Most people, by definition, are not minorities and are consequently at little risk of becoming such a victim. They are far more likely to become the perpetrators or their enablers.

In fostering identification with the victim, Holocaust memorials and exhibitions also foster identification with victimhood. This is particularly true in Germany, which has used identification with victimhood as a unifying principle for confronting its history, not only for the Holocaust but for all victims of war and tyranny. This approach, however, entails serious risks and unforeseen ramifications, especially in our current environment. It is all too easy to become a victim. Not only how we commonly understand the word, someone who is a victim of crime, discrimination, state violence, and so forth; that is, as a victim of history, incident, and acute societal circumstance, entailing a relatively clear demarcation of perpetrator and victim, a relatively clear apportionment of culpability. This is the victimhood we associate with minorities, those who are most vulnerable to its threat. But many others, whole communities, sometimes whole countries, are falling victim to intangible economic forces, no less calamitous, that are so swift and severe they would have once required theological exegesis; the human reality behind unhelpful terms like outsourcing, austerity, shock therapy, systemic risk, secular stagnation, financialization; unfathomable suffering caused by circumstances beyond the narrow realm of personal efficacy, what formally marks out those affected as victims. The problem is that very few people can cogently explain exactly who or what, in our absurdly complex economic system, is to blame for their misfortune, and even if the metonyms we use—“Wall Street,” “elites,” “Brussels”—are broadly correct, it is rather difficult to be mad at a metonym; the rage can easily drift or be directed onto less-savory targets, turning victims into perpetrators.

When everyone is a victim, no one is a perpetrator.

The dangers of the prevailing approach to popular Holocaust education and memorialization is exemplified in the way we speak about victims. Victimhood is now a hereditary attribute. Descendants of Holocaust survivors often identify themselves as such or are identified as such in the press, as though this confers extra moral weight to their statements, reveals some inherent and inherited virtue of character. I recently read an article that went out of its way to identify its subject as the great-grandchild of Holocaust survivors. This widespread practice points to a broader truth: A victim can never be anything but a victim. This is why some in Poland—among the worst victims of WWII, a tragedy amplified by the world’s general ignorance of its scale—have a difficult relationship with the work of Jan Gross, whose book, Neighbors, documents an appalling, unprovoked massacre of Polish Jews by their, yes, neighbors. Or why some in the Jewish community seem incapable of understanding that Jews can inflict harm on others. A victim is cognitively incapable of being, or becoming, a perpetrator. When everyone is a victim, no one is a perpetrator.

“What victims have in common is a lack of responsibility for their fate,” the historian Brian Ladd writes in The Ghosts of Berlin. When the most notorious crime of recent history becomes a prism to primarily identify with its victims, when its collective memory is staked on victimhood, it subtly inculcates the idea that we are passive observers of history; that our actions are fundamentally ineffectual; and, ultimately, it obscures the perpetrators. It is easy to imagine yourself powerless; it is much more difficult and not a bit disquieting to imagine why “ordinary men,” not all rabid anti-Semites, volunteer to shoot thousands of Jews in the head from close range. The purpose of Holocaust education is to imagine yourself the perpetrator, not the victim, lest the culprits become a perversely comforting parable of pure evil, detached from history and humanity, closed to our comprehension; and the Holocaust a mere tragedy, a fatal inevitability.

The perpetrators of the Holocaust are not absent from the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, which was not an initiative of Berlin’s Jewish community. One day I happened to be sitting near a tour group. The guide was telling the group about the history of the memorial and the controversies surrounding it. The memorial draws sharp reactions, he told the group. Just the other day, he went on, there was an older man who shook his head and said, “I hate modern art.” Some people in the tour group laughed. The philistine! The tour guide went on to talk about why he liked the memorial so much. Many people who dislike the monument probably agree with the old man’s assessment; maybe they don’t like modern art, or perhaps they don’t object to modern art but find it incongruent with the occasion; more than modern art, many probably just find it incongruent with the memorialized event. This last objection should be taken seriously. It is frequently raised in criticisms of the memorial. These writers, or visitors, fault foremost the memorial’s anonymity, its cold stone; or they fault the surrounding spectacle, the joyous romp of visitors, but the design is not strictly to blame for this—it could be managed differently.

These critics of the monument have correctly intuited the problem, but have arrived at the wrong conclusion. The issue is not its incongruence but, rather, its damnable congruence. Rather than memorializing “the murdered Jews of Europe,” as the name indicates it is doing, it is memorializing the Holocaust—its ideology, not its victims. The memorial approximates the perspective of the perpetrators, for whom there was no difference between a Yiddish-speaking Jew in Poland and a Ladino-speaking Jew in Greece; 2,711 Jews from Horodenka, 100,000 Jews from Budapest: no symbolic value, just a number: stelae of slightly different height. It is cool, scientific, modern, detached: the operational logic of the murderers reified. The most human thing about this memorial, the most genuinely rousing thing about it, is an occasional chip on one of the blocks. A pile of dirt, subtly shifted and altered by millions of footsteps, would have been a more moving tribute. A suggested intervention: Blow up the memorial and leave the rubble.

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is properly understood as part of a proliferation of Holocaust memorials and museums in recent years, many far from the countries where the Holocaust occurred. In the United States, for example, there are now more than 30 Holocaust museums and 20 Holocaust memorials, ranging from the well-known and well-funded (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington) to the obscure and somewhat baffling (the Holocaust memorial in Clarksdale, Mississippi). Today there are more than 300 memorials to the Holocaust and the Nazi era in Berlin alone.

The Holocaust memorial, detached from geographic reality, replaces an active memory of the Holocaust, informing our actions and decisions, with a monument to memory. It is a pilgrimage of performative guilt, a pilgrimage for performative contemplation of theoretical guilt; it expiates your imagined sins, leaving the real sins, and the potential for real sins, unperturbed. It allows its builders and visitors to wallow in self-regard, which, in part, explains the visitors’ behavior, the spectacle surrounding the memorial: They have already paid their penance; their presence is their penance. The memorialization of the Holocaust encourages external shows of remorse, external shows of enlightenment, external shows of sorrow, tailored and edited for an intended audience. It is selfies instead of self-examination. The internalization of the Holocaust’s lessons, conversely, engenders no immediate political or social capital.

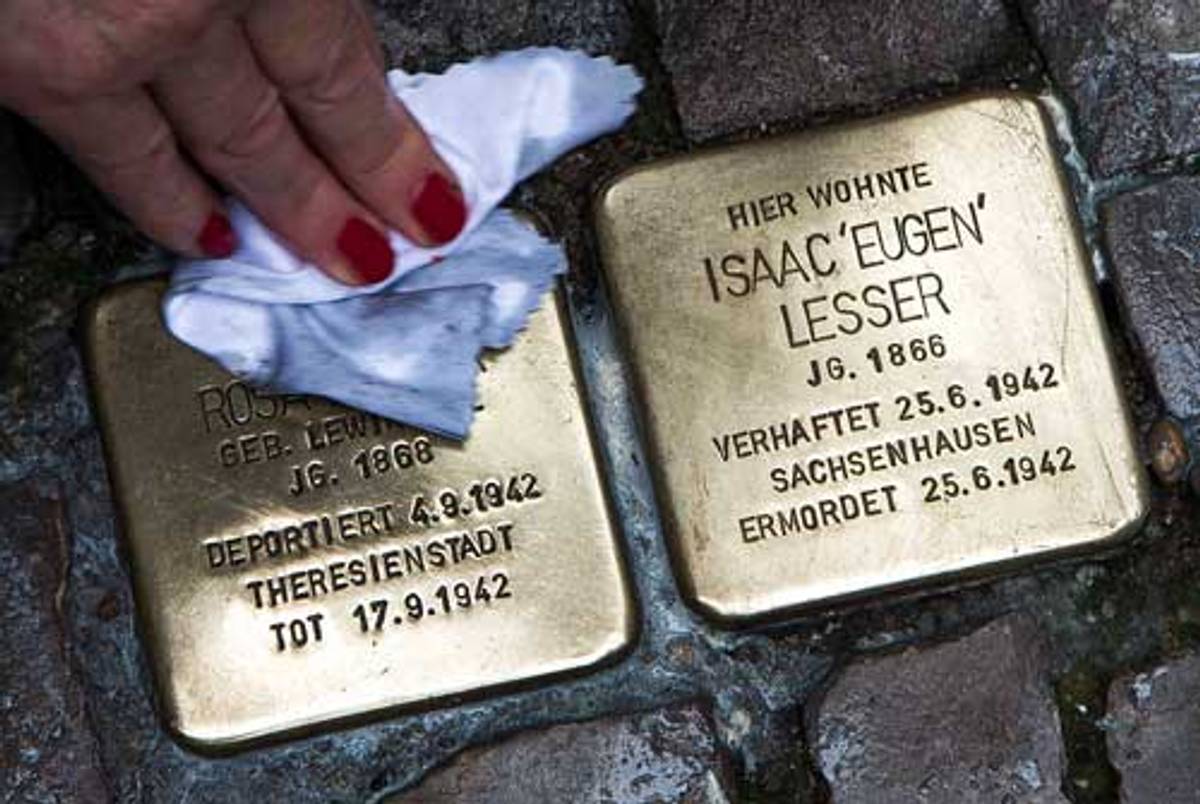

And yet, across Germany and Europe, an effective memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe had already started to appear in the 1990s. The Stolpersteine (“stumbling stones”) realize a simple, powerful idea: A small brass plaque is inserted into the sidewalk in front of the victim’s last known residence of free will; it gives his or her name, date and place of birth, and date and place deportation and/or death. (Any victim of German persecution, not just Jews, can be commemorated.) The Stolpersteine, which are not included in the 300 figure cited above, are the work of German artist Gunter Demnig, and what started as a solitary protest in Cologne has spread to 20 countries, with more than 50,000 plaques in total today. Anyone, descendants of the victims and ordinary citizens alike, can sponsor their installation, at a cost of 120 euros.

Like many civic initiatives, the Stolpersteine are superior to their official counterparts, and it also demonstrates why a site-specific memorial is always preferable: Geography ties us to history. (Other than its location in Berlin, the site of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe has no special relationship to the history of the Holocaust.) Every time I pass a Stolperstein—sometimes one, sometimes a family of two, three, or four—I stop and linger on the sparse information, the immensity of the lives that lay behind a handful of letters and numbers. Which apartment did they live in? How long had they lived here? And did Alfred Rosenberg whistle a tune every night (the same tune, perhaps) as he fumbled for his keys, anticipating the comforts of home? I have often seen others do the same, suddenly seize up from a meandering pace and hover over a plaque, momentarily dissipate into involuntary confabulation. And this is the true power of these brass cobblestones: They force you to think. Not just the production of a superficial thought—wow, dead Jews—but a basic philosophical definition of intellectual thought: to experience that sparse information from another’s perspective. Implicit in thinking of the lives of the victims is the lives of the neighbors—some of whom were surely perpetrators and many of whom were enablers. Did their children play together? Did they ever borrow a few spoons of sugar? And what did Frau Schmidt think, watching little Hans Cohn walk out of the house, never to return again?

Alex Cocotas is a writer based in Berlin.