Memories of Our Lost Soviet Youth

This May Day, a Jewish Refusenik looks back on the Spring of 1985

There are certain youthful memories that transcend the past in a way that makes it appear to have been impossibly perfect. This perfection of the past, especially if it occurs in a foreign language, corrects for immigrant anxieties and also compensates for exilic losses.

In the spring of 1985, when the events described here occurred, the political situation in the Soviet Union hardly promised any quick changes of fortune. The “rule of corpses”—Brezhnev’s latter years followed by Andropov’s brief stint on the Soviet throne—had ended in March 1985 with the passing of Konstantin Chernenko. The 54-year-old power-hungry Mikhail Gorbachev had just been elected general secretary of the Communist Party, and his grip on power was still tenuous.

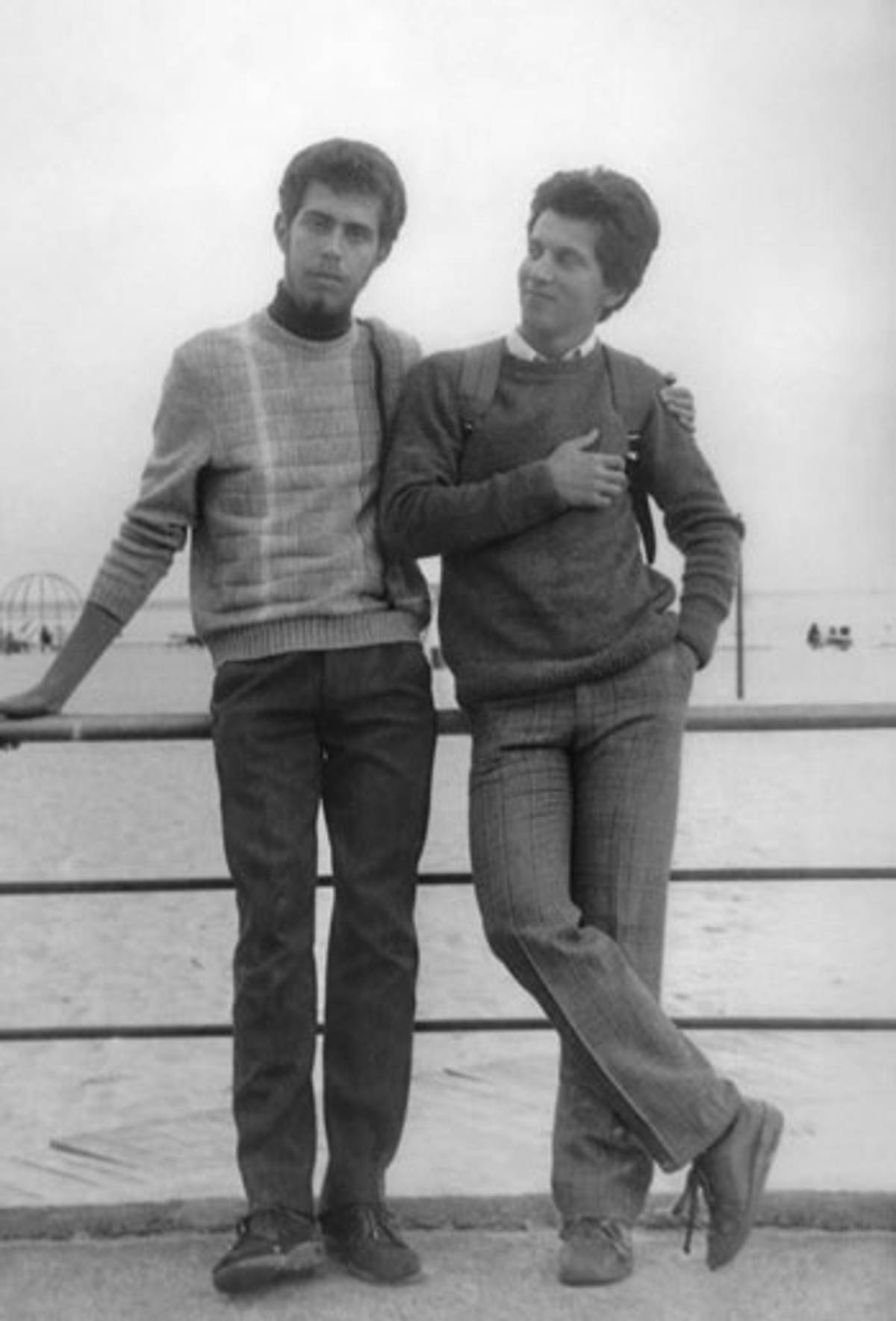

I remember a particularly fine Sunday morning in April of 1985, one of those liberating mornings in Moscow when everybody knows that winter is over. At the time I was a freshman at Moscow University, a kid from a family of veteran Jewish refuseniks. My friend Maxim Mussel (aka “Krolik=Rabbit”), now a marketing guru and a mobile filmmaker, was then a sophomore at the Moscow Electrotechnical Institute of Communications (nicknamed “Institute of Liaisons”). I left the USSR almost 30 years ago; Krolik is still living in Moscow—not far from the old haunts of our raw Soviet youth.

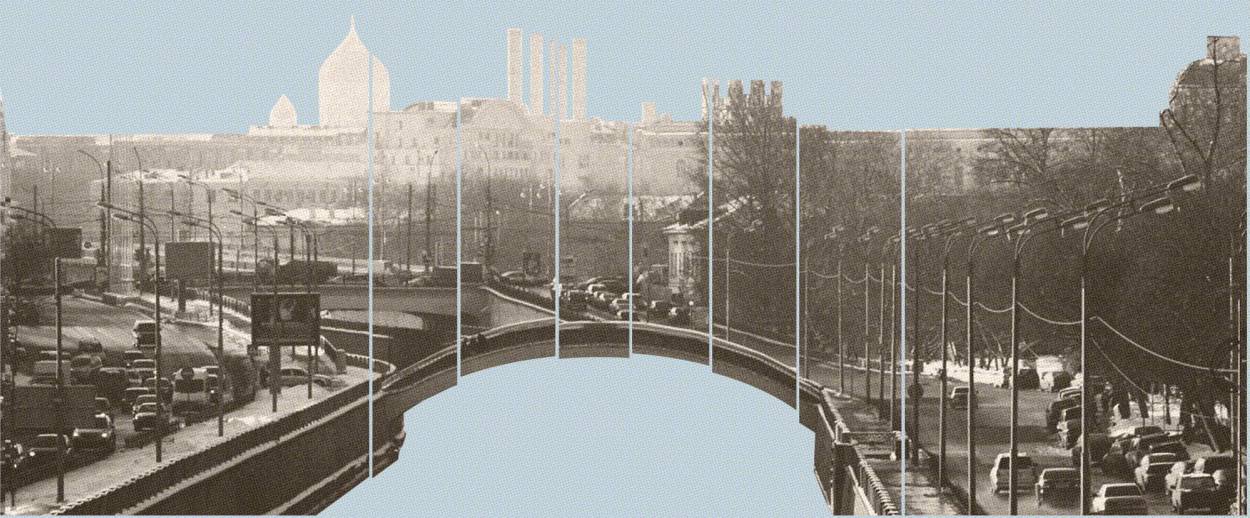

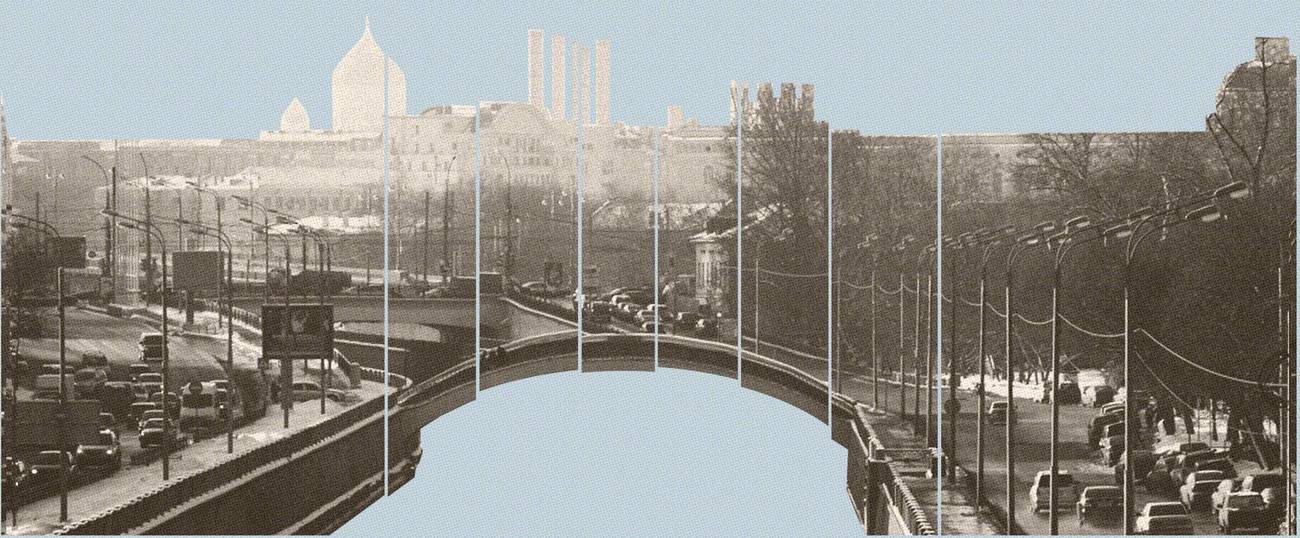

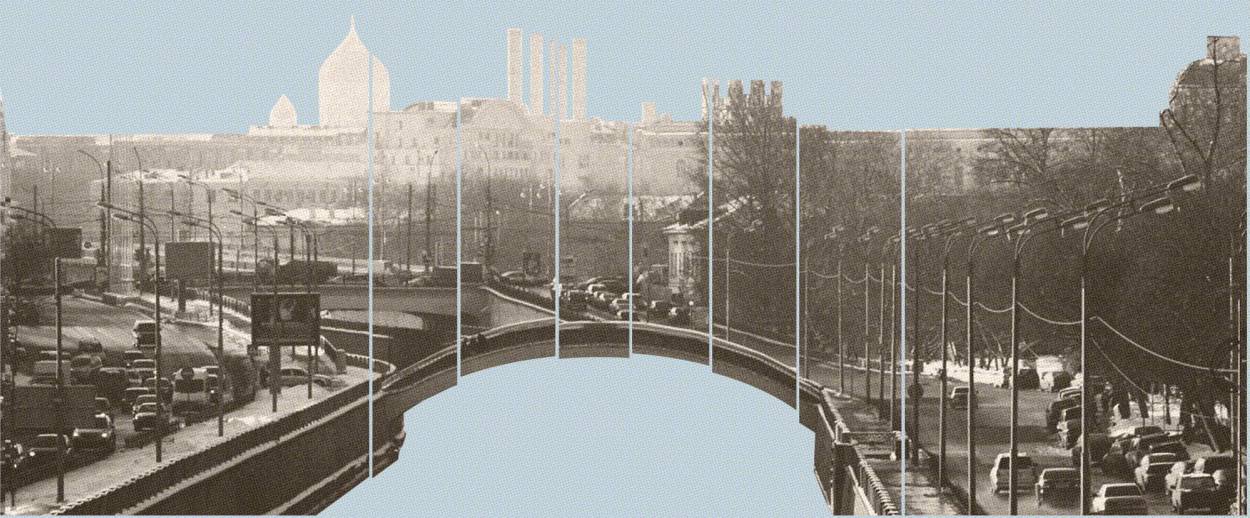

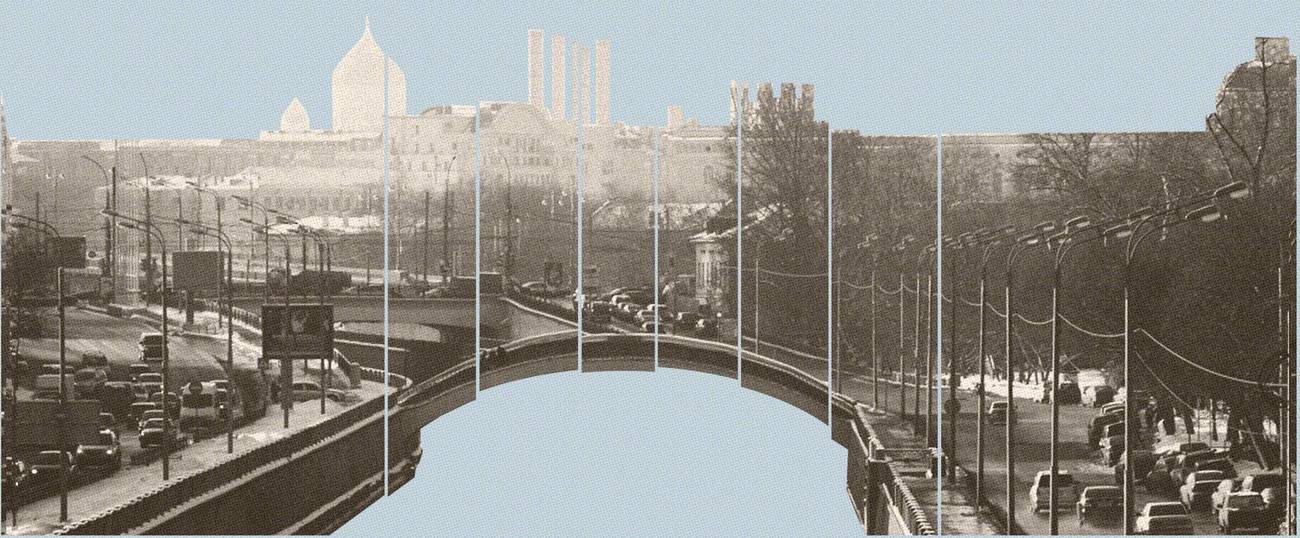

On that morning we met outside the Taganskaya Metro station, across the street from the Theater at Taganka, famous for its Brecht-inspired performances, and followed the streams of molten snow down Taganskaya Street to the Yauza River Embankment, past the Foreign Languages Library and in the direction of the Boulevard Ring, a succession of boulevards encircling the center of old Moscow. On their long necks, the waters carried down into the Yauza pieces of small urban debris, candy wrappers, sticks from Eskimo Pie bars, and beer caps, as we talked of Hesse’s Steppenwolf and The Glass Bead Game and also of Cortázar’s short story, which inspired Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Blow-Up. I was mainly reading Russian authors of past and present, instinctively distrusting translations. Krolik concentrated on non-Russian literature, especially Anglo-American, German, Latin-American, and Japanese—anything decent he could get his hands on in the Soviet book market. We were best friends and complemented each other: I a convinced Russophile in my reading habits, Krolik a sworn Westernizer; I a reader of poetry, Krolik of prose and screenplay translations; I a theater-goer, Krolik a fanatical film lover. Krolik was the main source of my knowledge of early Soviet and of Western cinema. He also knew most Beatles songs by heart. Krolik associated the Russian classics with mandatory high-school reading lists, and the Russian-language Soviet authors were to him either sell-outs or imitators; he made an exception for the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky.

Krolik and I lingered for a little while on the Tessinsky Bridge over the Yauza, studying the brackish, sun-splashed water. Then we strolled for awhile on a fragment of the Boulevard Ring, until we came upon a stekliashka, a cafeteria-bar with glass-paneled walls. It was about 11 in the morning and the stekliashka had just opened. Through dirty glass walls we could see early clients holding faceted glasses and resembling old lizards in a dusty terrarium. We entered the stekliashka and inquired at the bar (it was a self-service establishment) what they had to eat and drink.

“We’ve got jerez. And dumplings,” answered a tall woman of about 35, dressed in a low-cut lacy blouse and a pleated skirt. A bespattered apron was tied across her waist, while a semblance of a doily adorned the top of her head, like an Orthodox cross sitting on top of an onion dome. She uttered the short sentence and burst out laughing, coquettishly covering her mouth with both her hands like a true daughter of the Russian urban lower classes. The word jerez seemed so out of place in this establishment. Or did the barmaid laugh because not the wondrous word jerez but the awakening of spring intoxicated her, like the ether that a bored nurse inhales in an empty operating room?

“Jerez, 80 kopecks,” said the woman, whom the drunks congregating in the stekliashka called Valyushka, a diminutive of Valentina. (At the time university tuition was free, a Soviet student’s average monthly stipend amounted to 40 rubles, we were both living at home and couldn’t afford too much of anything without our families’ help.) In pronouncing the word jerez, Valyushka stressed the jer-syllable so sprightly that both Krolik and I thought she was testing the innuendo on us, two students who looked like they came from the Jewish intelligentsia.

“Excellent Crimean jerez,” she repeated again, now obviously stressing the jer (kher) part—kher, a Russian subliterary term which, in tone, would be equivalent to the American dick. Krolik and I each got a faceted glass of jerez and a plate of dumplings. We moved to a high table near the front of the cafeteria, from where we could see the boulevard. There were no chairs, and we stood there for awhile, like two horses, drinking our fill of this Soviet jerez and eating our vinegar-drizzled, clayish dumplings.

We were happy on that April morning. Krolik had just turned 19, I was turning 18 in June. Both of us longed to be someplace else, inside an abstractly composite long shot of a bar or a waterfront café, scents of good cigarettes, perfume, and whiskey tickling our nostrils. We talked, as we often did in those days, of what it would be like to find ourselves abroad. In the spring of 1985 the chances of this happening were nil, just as the prospects of change in the Soviet Union seemed nonexistent. Yet we still wondered what it would be like to sit in a bar overlooking Narragansett Bay. Krolik was finishing Thornton Wilder’s Theophilus North, a novel set in and around Newport, Rhode Island. (He would see Newport for the first time in the summer of 1989, when he first visited me in America.) We had both just seen Death in Venice with Dirk Bogarde at a Visconti retrospective, and we let our imagination run wild and pictured ourselves relaxing in a café in the Laguna. (In August of 1987 I would see Venice with my parents and a group of Jewish refugees traveling in Italy.) Once Krolik and I managed to transform the Soviet grunge and gruffness of our surroundings and insert ourselves into an imaginary panning shot of that fantasized Western bar or café, we went on talking about pressing matters: girls and each other’s romantic adventures, books and cinema, Jews and emigration…

In some memories of my Moscow youth I feel so oddly and bewilderingly at peace, that in moments of weakness I start wondering why I left in the first place. Had I experienced the best of friendships in the wrong place at the right time so I would then go on remembering the time even as I keep forgetting the place?

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Maxim D. Shrayer is a bilingual author and a professor at Boston College. He was born in Moscow and emigrated in 1987. His recent books include A Russian Immigrant: Three Novellas and Immigrant Baggage, a memoir. Shrayer’s new collection of poetry, Kinship, will be published in April 2024.