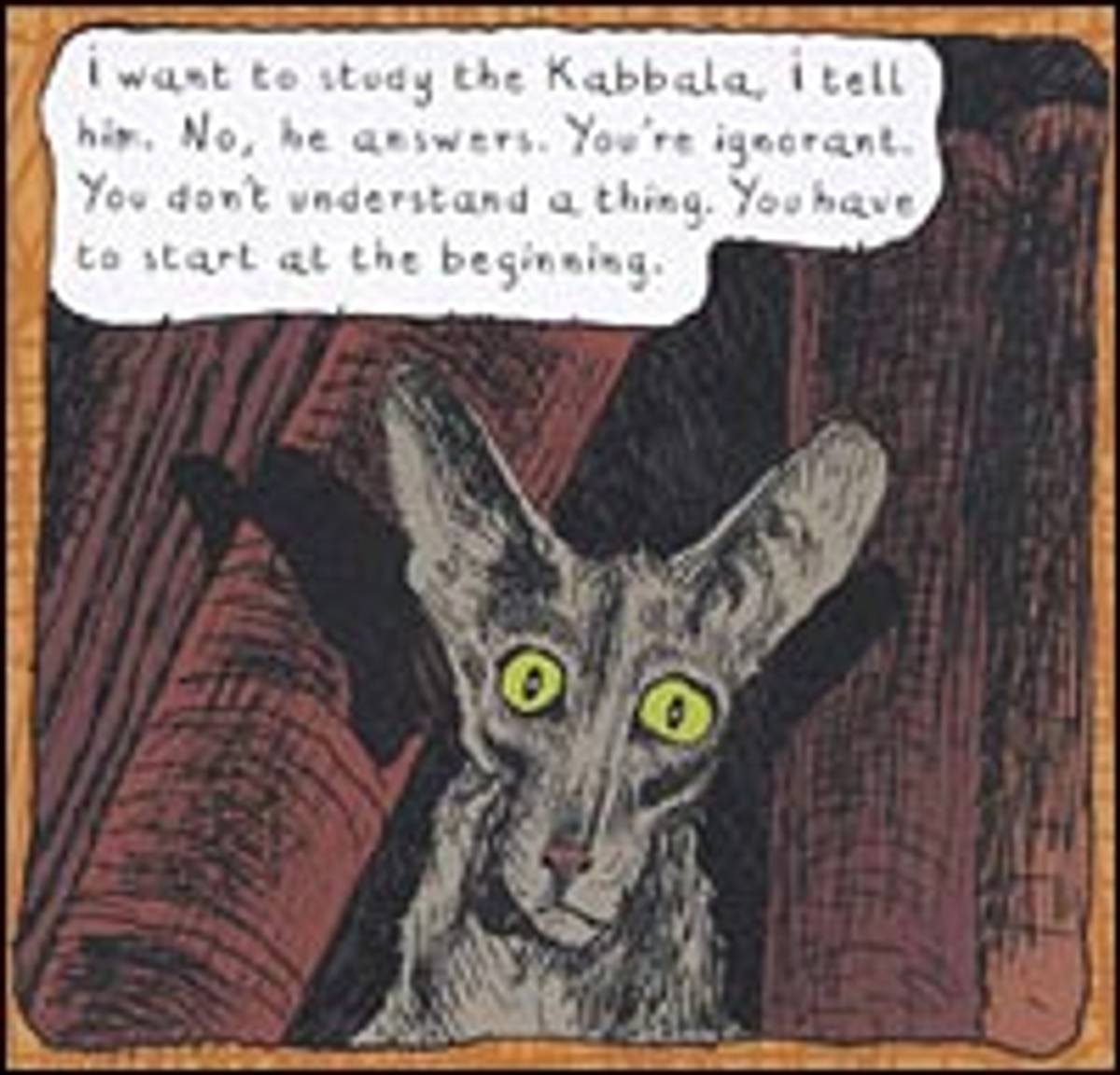

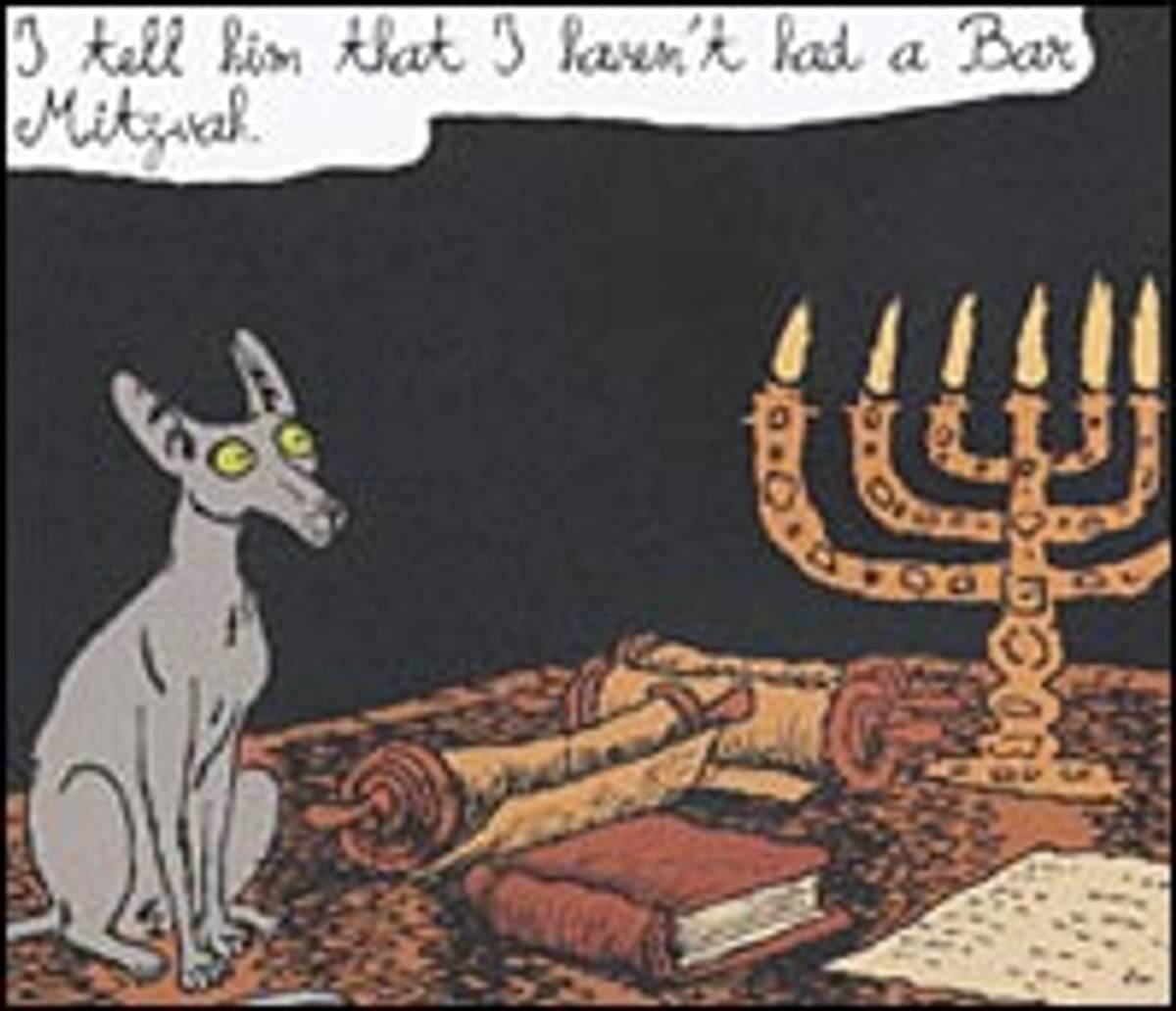

For anyone who’s ever gazed at their housecat and wondered what depths of wisdom and perversity lay hidden behind those half-closed, almond-shaped eyes, along comes The Rabbi’s Cat. French author Joann Sfar’s erudite, charming, and hilarious graphic novel, set in 1930s Algeria, stars an earthy old rabbi and a hyperintelligent, scrawny feline. This learned but skeptical animal, having miraculously developed the power of speech, argues with his master against the existence of God and the inanities of French colonial bureaucracy, but his primary concern is his ability to snuggle uninterruptedly in the arms of the rabbi’s beautiful young daughter. The cat narrates a tale that meanders from the medina of Algiers to desert oases where traveling Jews and Arabs make music together to the bohemian quarters of Paris, where Jewish assimilation is all the rage. Along the way, it richly illuminates a lost world, pulled between the lures of tradition and modernity.

Published in three volumes in France, The Rabbi’s Cat appears here this month, compiled into a single book and pungently translated by Alexis Siegel and Anjali Singh. Sfar, 34, says he began drawing comics at the age of 3, after his mother’s death; since then, he has written or illustrated more than one hundred albums for adults and children, often drawing upon his dual Ashkenazi and Sephardic heritage. Born in Nice, he lives today in Paris, with his wife, children, and two cats, including the model for his book’s hero.

I read that you were raised by your maternal grandfather. Is this so?

Not really, though he had a huge influence on me. He had studied to be a rabbi in Poland, but when World War II came, he was already in medical school in Paris. He renounced his religion and became a military doctor, fighting with the French partisans. In the Resistance, he was an aide-de-camp to Andre Malraux. Anyway, he was the one who taught me about Judaism—with a lot of irony, because he didn’t believe in God at all. He considered the Torah a sacred text because of its literary nature.

And your father?

My father’s family comes from the region around Oran, in Algeria. He was a student in Algiers in 1957, when he was physically attacked by extreme right-wing French forces for siding with his Arab friends during a university strike—the right-wingers beat him up and put him in the hospital for three months. So he made the French authorities offer him police protection until he finished his law exams, and then he left the country.

So heroic masculinity runs on both sides of your family.

Yes, but it’s difficult to be raised by two dominant males. Both my father and my grandfather, each in his own way, were traumatized by the idea, then quite common, of a certain Jewish passivity. They were capable of going to extremes of activity, resistance, even anger. So me, I tell stories. I find that more restful.

Have you also tried your hand at more traditional fiction?

Yes, I wrote and illustrated a novel called L’homme-arbre [The Tree Man], which appeared last year in France. The sequel is coming out next month. It’s a Hasidic fantasy tale—a sort of Jewish Tolkien.

The Rabbi’s Cat begins with the cat explaining that “Jewish people aren’t crazy about dogs.”

Yes. I have a very religious cousin who lives in Bnai Brak, in Israel. When I was little and wanted a pet, he said, “Get a cat.” Because from a Talmudic point of view, you have a lot to learn from a cat, while you have nothing to learn from a dog. He’ll just make you look Polish.

I was under the impression that religious people weren’t big fans of domestic animals in general.

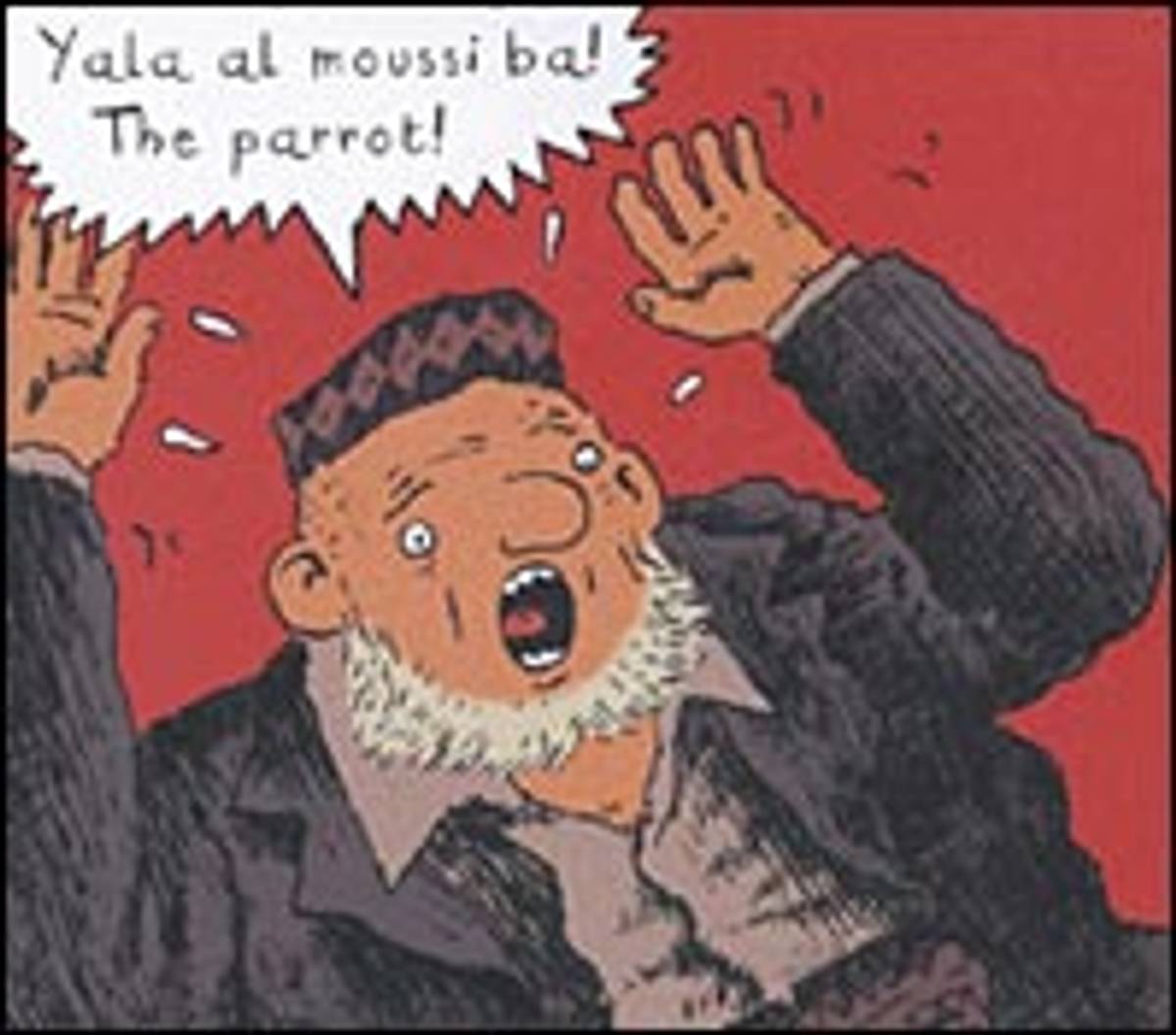

I’m not so sure. I knew an Algerian rabbi whose parrot repeated every word he said. And there are many symbolic stories about animals in the Talmud.

What were your sources for the philosophical discussions between rabbi and cat?

There’s a lot of stuff in there that I vaguely remember from Hebrew school—things people told me that at the time I thought were stupid, but then they came back. A lot of childhood memories.

Did the tense situation of the Jewish community in France today shape your thinking about the book?

Most certainly. I discovered that most French people had a Jewish guy in the classroom, but they never went to his home for Shabbat. So I wanted to invite my readers into a Jewish home, to sit at a Jewish table with a Jewish family. There are many fantasies about Jewish people in circulation. I wanted to normalize that vision.

That said, I think the idea of seeing France as an anti-Semitic country is just a mistake. There are in fact two problems. The first has to do with French guilt over World War II and the Algerian war. So whenever the subject of Jews or Arabs is on the table, people can’t think freely and in a simple way. The other problem is that the young Muslim guys living in France today aren’t taught about the dangers of racism. I do my best to work on this. Because I go into many classrooms in difficult suburbs of French towns, and I’m often the first Jew these kids have ever met. When they think about Judaism, all they know is Ariel Sharon. At the beginning of the lesson, it’s sometimes a bit tough. And at the end, they’re interested.

Why?

Because they realize that there used to be a lot of Jewish people in North Africa. Then they realize that they don’t come from Palestine, and neither did my ancestors—most of us came from North Africa. You know, young French Arab guys think they’re Palestinians. And young French Jewish guys think they are Israelis. It’s very sad. They talk about this subject as if they were discussing a soccer match. I don’t want to suggest that Jews and Arabs behave the same way. The Arab guys are very violent, whereas Jews are not. But from a moral point of view, I think there are problems in both communities.

For instance, I was raised in a family where my father and other people made me feel guilty about not living in Israel. I have a lot of tenderness for Israel, but I’m much more attracted to a vision of Jews in the Diaspora. I am a Zionist. I want Israel to exist. But I don’t like the idea of solving the Jewish problem by giving the Jews a land. I think you can have as many lands as you wish; the Jewish “strangeness” will not disappear.

Meaning?

You wake up in the morning, and you say, I hope they still love me in this country. But for them to love me, I have to write books, I have to make good music, and so on. I like this idea.

So I guess the choice of comic books as a medium—

That’s my language. But it’s useful.

It’s useful for reaching out to young audiences, and across communities.

Yes. When I first came to my publisher, my stories were very intellectual and complex. And he told me, “You manage to make intelligent stories for intelligent people. Any idiot can do this. But to make an intelligent story for everyone—that’s something to be proud of.”

How did the Jewish religious community in France respond to The Rabbi’s Cat?

I feared they would hate it. But I had many letters of congratulation, especially from wives of rabbis. The head of the French rabbinate even sent my publisher a certificate proclaiming my rabbi to be an official rabbi of the French community. And he told me that my characters’ criticisms of religion are exactly what rabbis wait for a good pupil to do. In a yeshiva, if a pupil doesn’t criticize the text, he’s just bad. Because they say, the law is stronger than you. Your role is to fight against the law to make it even stronger. And I don’t consider Judaism to be something fragile—for me it’s not like a crystal glass. I can give it a hit, and it remains very strong.

I didn’t think The Rabbi’s Cat was a book against Judaism. But it’s about different kinds of belief and ways of practice, and against fundamentalisms of all kinds.

My rabbi is not a modern guy. He’s very old-fashioned. He’s not an intellectual—his relationship with religion is very down-to-earth. He doesn’t really care about God’s existence. He just cares about what he has to do every day. I like the idea of his coming back from Paris and saying that he doesn’t know if there’s a God or not, and then he goes to pray. Many people forget about this relationship to religion as a daily practice. But I’ve always preferred the sayings of my grandma to the dictates of my grand rabbin.

Leslie Camhi’s first-person essays and writings on art, photography, film, design, fashion, and women’s lives, have appeared in the New York Times, Vogue Magazine, and many other publications.

Leslie Camhi’s first-person essays and writings on art, photography, film, design, fashion, and women’s lives, have appeared in The New York Times, Vogue Magazine, and many other publications. Her translation from the French of Violaine Huisman’s award-winning debut novel, The Book of Mother, was published this month by Scribner. She’s on Twitter @CamhiLeslie and on Instagram @drlesliecamhi.