The World as They Found It

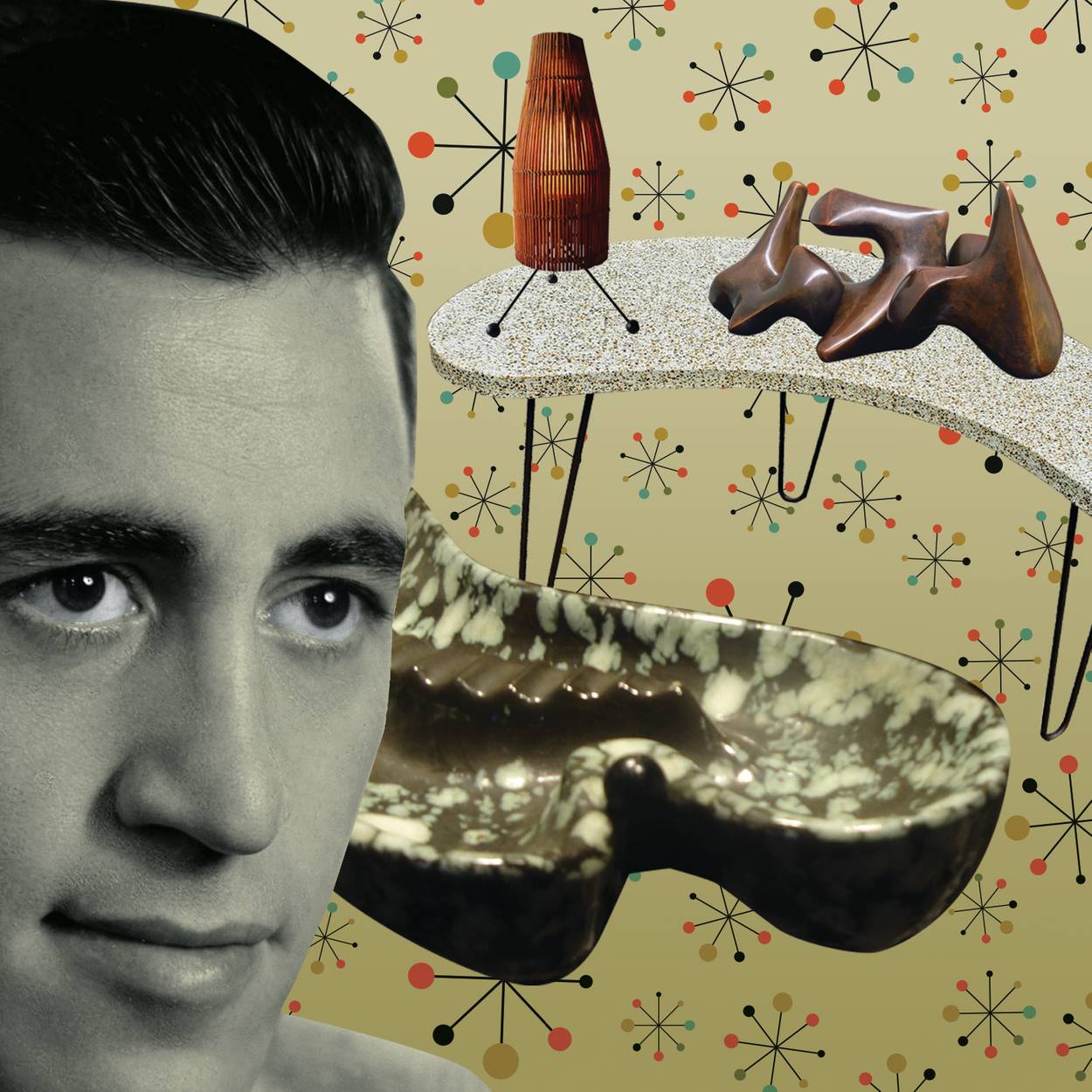

How the midcentury modernism of J.D. Salinger and George Segal reflected an American Jewish generation

Haimishkeit—longing for the world as we found it. Looking at the images of contagion teams dressed in what seem to be pastel-colored spacesuits or remembering New York’s beautiful and dystopic 7 o’clock clapping, horns, and pot-banging, I wonder if there could ever have been a time when I’d be more in mourning for the vanished world of my childhood.

I was born in Chicago in 1950, exactly mid-20th century. Modernism, intended to deflect the mistakes and calamities of the past, was overlaid onto the zigzagging split-levels starkly plunked into the suburb where my family lived. Midcentury modernism brought Formica and glitter laminate into our kitchens, my friends drank out of colored aluminum tumblers, and our parents stamped out their cigarettes on the splotched surfaces of copper enamel ashtrays. When I was a child, I didn’t like the whacky style of the era which I understood subliminally as a deflection against the invisible, broken world that drifted around us but seldom touched down. After all, it was only seven years before I was born when my grandfather received a personal message from the International Red Cross, concerning two cousins, their spouses, an aged aunt, an elderly uncle, and the uncle’s “large family, previously from Kezmarok, Slovakia” but now in “the General Government, previously Poland.” And it was two years after that when my father, onboard a naval ship in Okinawa heard about a superbomb and the surrender but, as he said, “no one believed it.”

When my kids were young, I didn’t feel nostalgia for midcentury or for the cat-eye sunglasses and vintage chiffon party dresses which were beginning to find their way into high-end resale stores. In fact, I associated them with unexplored trauma and intolerance which my generation had confronted in the 1960s and early ’70s when we were trying to find another way forward. But we become specialists in what, by chance, we’ve lived with. Over the past decade I’ve found myself writing often about those things that were hidden in plain sight during my childhood.

Artistically, Jewish designers, sculptors, painters, composers, and writers were often in the forefront, perhaps because they were carriers of culture from the vanished world or voices for those who perished in the European tragedy. On the one hand, Jewish émigrés were a direct link to a heritage that drew strength from skepticism and experimentation and these were now requirements for honest reinvention. On the other hand, American Jews, whose parents or grandparents had been immigrants, often straddled two worlds and the uneasy tension made them natural conduits for dynamic energy so badly needed after the war.

In December, before stay-at-home orders or the NY PAUSE were conceivable, I found myself strolling through two art exhibitions that bracketed the modernism of my childhood. New York Public Library had put together a J.D. Salinger exhibit, a small collection on loan from the Salinger Literary Trust, marking what would have been the author’s 100th birthday. And the Jewish Museum in New York was presenting the sculptor George Segal’s Personas: George Segal’s Abraham and Isaac, an adaptation of the biblical story to commemorate the tragic shootings at Kent State.

Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, his first book, was published when I was a 1-year-old and the Kent State shooting happened when I was halfway through college. From the vantage point of midcentury, Salinger’s stories and novellas, haunted by the war, told us how we had gotten where we were and who we were before we got there. Segal’s bandage-wrapped figures—metaphors for the dead who were ceremonially preserved or the injured whose wounds had been dressed and protected—provided closure to the howling pain.

The Salinger show, curated by the library’s director of special collections along with the author’s son and widow, delicately navigated some troubling biographical issues (his habit, for instance, of excising people from his life, such as the many members of his father’s extended family, his first wife whom he married in Germany, his daughter Margaret, as well as the writer Joyce Maynard with whom he initiated a relationship when she was a freshman at Yale and he was 53). Nonetheless, the memorabilia offered some insight into the man who had held a mirror up to his generation, for better or for worse.

It presented photographs from Salinger’s 1920s childhood (in his baby carriage, with his sister, with his puppy); his debossed and notched army dog tags (almost everyone from my generation will remember how our fathers stashed these away in little cardboard boxes or drawstring bags); and typescript versions of his stories anchored in the 1940s and early ’50s. There was as well a revolving bedroom bookcase with his idiosyncratic collection of faded volumes including the Poems of Emily Dickinson, The Old Tea Seller, Day by Day with Bhagayan, Lost Horizon, The Most of J. Perelman, and I.B. Singer’s The Estate.

Salinger’s writing, with its modern, empty spaces embedded in the narration, has always resonated with me in a deeply subjective and personal way, both because it came out during my childhood and adolescence and because of a series of haphazard coincidences. My father, just about the same age as Salinger (and exactly the same age as Salinger’s protagonist, Seymour Glass), was raised in a similarly assimilated, secular, and upwardly mobile Jewish family. In 1929 when Salinger spent the summer at Camp Lincoln in the Adirondacks (a small copper bowl he made as a camper and kept with him his whole life was displayed in the show), my dad was at camp in Wisconsin. Both were sent to military academy for high school and later served in a war where they saw terrible things and judged themselves (as well as the American military, in general) severely.

My mother was slightly younger but from the same milieu. Her father’s best friend wrote songs for Tin Pan Alley and Broadway and a family of quiz kids, like the Glass family, was part of their close-knit circle of friends. Like the Glass family’s apartment, the house my mother grew up in was filled with assorted models of radios and phonographs, “comfortable and uncomfortable chairs,” bridge lamps, Nancy Drew books, as well as leather-bound copies of Dracula or Confessions of an Opium Eater and book club books. In my grandparents’ house, most of this paraphernalia was meticulously stored in boxes in the attic but, like Bessie Glass, my grandmother kept the grand piano in the living room open. Exceptionalism was something her generation was on the lookout for. Like Salinger’s characters their friends talked about Freud and psychoanalysis while they inflected their conversation with jargon from the depression and the war years: “for the nineteenth time,” “funny business,” “dopey,” “don’t be fresh.”

When I was a little girl, adults smoked like crazy and spoke with the same irreverence and sarcasm as the characters in Salinger’s stories. The minute I read “Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut,” I recognized myself inside the contours of the little girl who kept an imaginary friend to ease her loneliness and anomie. When I read Franny and Zooey I instantly understood the magnetic pull of The Way of a Pilgrim.

The hunger for spiritual peace permeated Salinger’s stories and, even while his books were bestsellers, some critics called them sentimental and others insinuated that the author was a fishy kind of Jew, writing about the offspring of a mixed marriage who spent their days contemplating nonkosher belief systems in order to navigate trauma. The NYPL exhibit included examples of little guidebooks Salinger made for himself (he called them “vade mecums”), containing handwritten and typed quotations excerpted from Hindu, Jewish, Islamic, and Christian mysticism. One of the highlighted passages came from the Zen teachings of Huang Po on the Transmission of Mind: “While you are not thinking of good and not thinking of evil, just at this very moment, return to what you were before your father and mother were born.” I remember, after a death in our family, my father, who on the surface was the least spiritual person on earth, saying a variant of the same thing, “I wish I was a little boy again at my grandfather’s house.”

In the midcentury I lived in, we resided in the narrow space that existed just across the boundary line from the catastrophes of the 1940s. For my friends who grew up in Europe, those in postwar Poland, for instance, the separation between past and present was permeable (even though any mention of recently deceased Jewish grandparents was unthinkable). In Warsaw you went to bed at night with the sound of dynamite bringing down the wreckage of your city; the disintegration of the past was spectacularly real. But in America, the calamity happened overseas and there was an assumption, among a certain set at least, that the sadness could be left across the ocean. If you carried home your private ruin, the honorable thing was to tamp it down.

My father’s anti-heroic stories about the Pacific theater came out sporadically—memories of interminable, pointless incompetence with screwball superiors like the shell-shocked commander who always wore a battle helmet and was eventually court-martialed for lining up his boats like ducks in a pond. Salinger, whose regiment had been in the forest at Hürtgenand had seen Kaufering, one of the subcamps of Dachau, carried memories from the war years forward into midcentury. He encapsulated the rage and the jumpiness of that time in his writing and this was most distilled in the portrait of Seymour Glass (“See more glass,” is the word play) who, three years after the war, shot himself in the head with a German-made pistol while sitting on a twin bed in a Florida hotel room.

Americans, at midcentury, were thinking about squandered lives and simultaneously suppressing that thought. One rainy evening in Chicago in 1951, the gentle young man, who had been the groomsman in my parents’ wedding in 1949, drove over the barrier on Lake Shore Drive and his car flipped into the air and somersaulted down. My mother told me they went to see the tire tracks on the grass embankment the next morning. “And he survived the war,” she said quietly. Inadvertently, Salinger’s stories presented the blasphemous, unarticulated, but widely shared viewpoint that war was a monstrous absurdity.

Because we knew what our parents had experienced during the war years, a profound sense of betrayal lay at the core of the generational conflict of the 1960s and early ’70s when two wars were running concurrently. The real war, the incomprehensible war in Vietnam, was being waged in Southeast Asia while the shadow war, the war against the war, was being fought behind closed doors in our houses, on the streets, and on college campuses.

In the beginning, the weaponry was exhilarating—street theater, rock music, long hair, beards, granny dresses and granny glasses, Salvation Army jackets, and hash brownies. It soon escalated from thrown stones and broken bottles to bonfires, tear gas, machetes, mace, handguns, rifles, and bombs. The tragedies at Kent State, which occurred at the end of the first weekend of May in 1970, crystallized something profound about confrontation and conflict between the generations as well as the unspoken-about trauma that lay between us. In the blur of memory, I can still feel the disequilibrium of that turning point and the grief under the rafters or roofbeams in the chapel at my college. I remember thinking about something my father had once said. He had been on a destroyer in the Pacific when Roosevelt died. Unsentimental to his core, he had asked himself, how the hell are we going to get out of this now?

The Jewish Museum has called George Segal’s “Abraham and Isaac (In Memory of May 4, 1970, Kent State University)” a funerary monument and I think that’s correct with an important caveat that I’ll get to. Segal, roughly the same generation as Salinger, came from a different background and aesthetic. Born in New York in 1924, he was the son of Polish Jewish immigrants who operated a kosher butcher shop in the Bronx. In the 1930s the family moved to New Jersey to become chicken farmers. Like Zionist pioneers, they were social idealists, committed to working with their hands and working the land, respectful of science and technology and unsentimental about the practice and meaning of slaughtering animals. Segal, in fact, recreated the butcher shop in his wonderful 1965 assemblage, complete with cleaver, bone saw, and a plaster cast of a chicken suspended on a hook beside a plaster cast of his mother standing at a butcher block table.

When he was a young man, Segal and his wife moved down the road from his parents, establishing their own chicken farm as a means to support his art; and their farm, as it turned out, was the site of the first Happening organized by Allan Kaprow. Segal had started out in the art world as a painter but in 1961 he began experimenting with plaster-impregnated bandages, making body casts of his friends and family. The idea was that by taking impressions of his models—this included their whole bodies, their faces and hair, shoes and clothes—he could achieve a transference that would leave the mark of emotions and what he called “mental life” while the artist’s fingerprints and tool marks were also imprinted on the surfaces.

In many ways, the process connected him to ancient burial preparations, funeral masks used as mementos of the dead, and the iconography of the Veronica cloth which was said to have been impregnated with the spirit of Christ, the dead god. But the new medium also challenged ideas about artistic control and artistic expression and countered the premises of more cinematic and Bogart-esque confessions that seemed modern in Salinger’s stories.

Although Segal said he wasn’t concerned about the significance of his materials—what he loved was its plasticity, that it could be remodeled in an infinite number of ways—it was impossible for his early audiences to separate the figures from their bandages and this is reminiscent of another and much earlier Jewish artist, Soutine, whose flayed beef and hanging turkeys were masterpieces of painted coloration but couldn’t be entirely severed from the bloody carcasses on butcher hooks which were their models. When they first appeared on the art scene—and I remember the shock they created in the 1960s—Segal’s bulky, stark white figures looked like messengers from another planet, zombies, or phantoms.

Segal’s works caused you to laugh but there was also something chilling in their spectacle. They were existentially alone since they were encased inside the material of their skins, seemingly paralyzed since the material of their skins had long ago hardened. You had to ask yourself, were the bandages for the souls of these creatures or for their bodies which balanced unsteadily, just as we did, on the verge of becoming something else.

When Segal chose the story of the binding of Isaac to memorialize the ambiguities and complexities of the tragedy at Kent State he was rummaging through his childhood and cultural roots. In his parents’ butcher shop, mammals and birds were slaughtered according to kashrut and the killing was neither emotional nor romanticized; rather it was done by following Halacha. In his design for the monument, he was thinking about the loss of life at Kent State but he wasn’t trying to resolve its difficulties and contradictions. Rather, he was preoccupied with the problem of understanding. As he put it, “I have a sense that I was that student yesterday and I’m the father today … the story of everybody’s life is that turn of the wheel and reversal of role … the real issue is about the warfare of the generations.”

Like all of his work, the piece was intended to be anti-heroic, anti-authoritarian, and improvisational. Instead of putting the biblical figures on a platform, he placed them on a built-up sheath of rock around which you can walk so that the catastrophic confrontation of obedience and responsibility is happening in your real space.

Segal pared down the biblical narrative so that the tension was translated simply into gesture and muscle. Segal’s Abraham held his spine straight (“ramrod straight” is how Segal put it). Isaac lifted his chin. Abraham clenched his left hand, the hand that wasn’t holding the knife, demonstrating the psychological strain where faith, aggression, love, and obedience come together. In this way, Abraham embodied both the patriarch and the traumatized generation that had fought the wars of the 1940s. Dressed in work clothes, so similar to the Army-Navy-wear so many of us wore at the time, he could also represent the 28 National Guardsmen who had fired into the crowd of unarmed college students, shooting 67 rounds of ammunition in 13 seconds.

While the sculpture is indeed a funerary monument, the exhibit at the Jewish Museum is more like an archive for the project. The show includes the famous picture (later cropped for the cover of Newsweek) of Mary Ann Vecchio, arm stretched out in grieved confusion, half-kneeling by the body of Jeffrey Glenn Miller who was lying flat and face down on the ground. Segal’s somber preparatory drawings for the sculpture stand in stark contrast to the lurid colors that sensationalized the event for the magazine. There’s also documentation about the Kent State commission and its cancellation when the university administration, in the words of the president’s assistant, “felt it inappropriate to observe the killing of four students and the wounding of nine others with a sculpture that indicates someone committing violence on someone else.” When they requested changes, Segal withdrew the project and arrangements were made for the work to go to Princeton. The finalized bronze “Abraham and Isaac” was dedicated in 1979 behind Princeton’s university chapel and it remains there today in exile, a funerary monument intended to bind the pain and grief of a dreadful historical moment.

If midcentury modernism began with the tormented return of our parents to civilian life, assumptions about freedom and responsibility shifted when Segal’s plaster-wrapped and neorealistic figures lumbered into the world. I wonder about this enormous and decisive moment in our history, a time of pandemic and political upheaval, disfiguring and also transforming patterns of human life and intimacy around the globe. Art has always helped us think about where we have been and where we are going. Because so much creativity has come unexpectedly to the fore already, combatting and binding our pain and grief, I’m willing to find some pleasure in anticipating what will be next.

Frances Brent’s most recent book is The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson.