Mindless Violence

The Baader-Meinhof Gang had all the brains of an action flick

The exploits of the Red Army Faction, better known as the Baader-Meinhof Gang, may be the subject of a new film, but, in truth, the group was movie material from its inception.

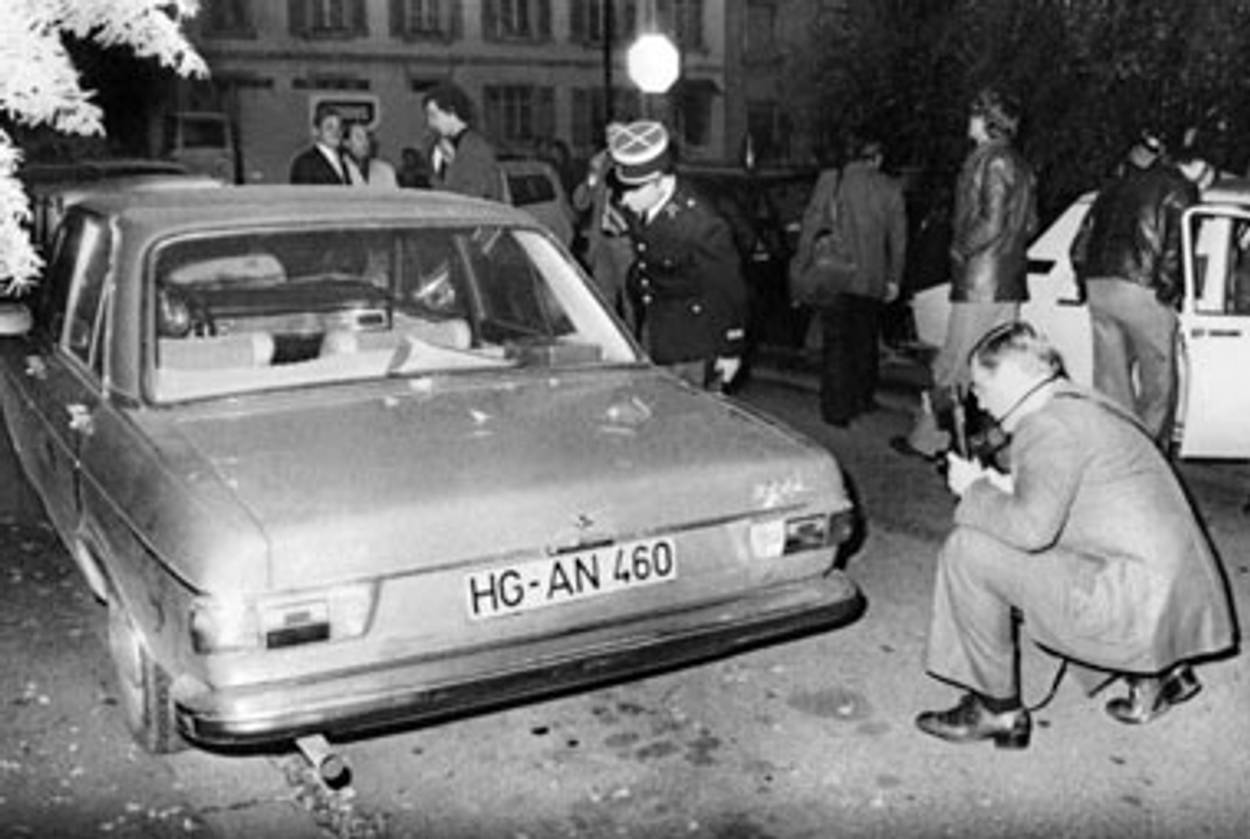

The Gang, which paralyzed West Germany in the 1970s, was a hallucinatory cult of would-be Maoist urban guerrillas who over the better part of a decade hurled Molotov cocktails, robbed banks, bombed American military bases, kidnapped and killed government officials, businessmen, and police, arranged to hijack a passenger plane, drove the police crazy, drove the media wild, immolated themselves and others, and succeeded in galvanizing the young of West Germany into vicarious roles in a self-conceived urban guerrilla war—against, as they said, imperialism, the Vietnam war, Israel, and consumer capitalism.

As they careened along their arc of moral giddiness toward the apocalypse, the Baader-Meinhof Gang had all the heart and brains of an action movie—no surprise, since in more ways than one they were inspired by action movies. The German journalist Stefan Aust, who worked with Ulrike Meinhof during her journalistic days and wrote the book on which the screenplay of director Uri Edel’s new film The Baader-Meinhof Complex is based, told Fred Kaplan, writing for The New York Times, that the charismatic young tough Andreas Baader liked to tell people that “his favorite movies were Bonnie and Clyde, which had recently come out, and The Battle of Algiers.” Baader, the star-leader, had an eye for branding, and paid “a designer to make a Red Army Faction logo, a drawing of a machine gun against a red star.”

What the Group wanted was nothing short of “total revolution,” in the words of one of its ideologues, Gudrun Ensslin, who once exclaimed: “in order to get no less than everything, in order to be liberated, means hate, means an effective killing machine.”

Language like that points to an ideological slipperiness resembling today’s jihadists’—a slipperiness that would have been wrestled with in a sophisticated film, which Edel’s effort is not. It was, after all, something of a sentimental convenience and something of a generational accident that Baader-Meinhof declared themselves to be on the Left at all. As the film doesn’t note, Ensslin as a teenager was partial to some views that would conventionally be called right-wing, along with others that would ordinarily be considered left-wing. Their lawyer and ideological counselor, Horst Mahler, now in his seventies, has spent his last dozen years as a professional anti-Semite and is currently serving a long sentence for Holocaust denial. But action movies are not strong on backstory, let alone exploring a history in which the modern party that most efficiently transformed itself into a “killing machine” called itself the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. It’s a pity that a two-and-an-hour-long movie is so busy with capers and shootouts that it fails to explore this—to say the least—interesting topic.

As the film does make plain, Baader-Meinhof’s “issues” (to pirate a line from the 60s) , were not the issue, nor was their analysis lucid. They were not a political party dickering over a platform, nor a vast movement piecing together a plausible strategy out of some inchoate but slowly clarifying sentiment. The Baader-Meinhof Gang longed for the absolute, the utter purgation, the ultimate purification, the overthrowing of everything less. Their intoxication was not original to them. The bringing down of the pillars (let them fall where they may) is a grand theme running throughout German romanticism—and, the lust for the final apocalypse was not only German. It was an American radical who said in 1969, as a faction called the Weathermen were readying themselves to go underground to plant bombs, “I feel like turning myself into a brick and hurling myself.”

The gang’s trajectory was full of bang-bang and blow-up and stick-your hands-up, and their flamboyant car thefts, fire fights and ambushes, combined with ham-handed police responses, galvanized millions of young Germans who were at least half-consciously looking for a way to hold their parental generation accountable for Nazism, at a time when the upper ranks of German society (including the prime minister between 1966 and 1969) was, in fact, riddled with former Nazis. Ensslin (played by the spunky Johanna Wokalek), who turned her fierce, ignorant boyfriend Andreas Baader into a Leninist-talking household name, once told a group of less ferocious radicals: “You can’t argue with people who made Auschwitz. They have weapons and we haven’t. We must arm ourselves!”

This was in 1967, after a West Berlin policeman killed a protesting student for demonstrating against the Shah of Iran. From Ensslin’s lips to the ears of the young thief Baader, whom she introduced to the joy of anti-imperialism, and soon, together, they were planting two firebombs in department stores in Frankfurt am Main, for, in Ensslin’s frame of mind, West Germans were lost in a stupor of consumerism, and only firebombs would blow them out of their apathetic collusion with the forces of imperialism.

Of this conviction, Ensslin’s father, a rigorous Lutheran minister in the grip of noble angst, said during her trial that she reached “a state of almost ecstatic self-realization, of holy self-realization.” It was perceptive of him, if chilling, to speak of his daughter’s transfiguration in Gnostic rather than intellectual terms, for the faction’s ideas were the barest of bones. Baader himself had all the ideas of a Molotov cocktail, and the sensuous-lipped Moritz Bleibtreu plays him that way. The closest the movie Baader gets to a thought is this remark he throws at Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine guerrillas in a 1970 Jordanian training camp when they object to the bare-breasted female Germans: “Sexual revolution and anti-imperialism go together. Fucking and shooting are the same.” Ejected by the Palestinians, Baader & Co. headed back to Germany to resume their lethal adventures.

If the movie passes lightly over the ideas that were presumably the point of the crusade, then, it is in this respect accurate, as when the movie’s Ensslin confronts the journalist Ulrike Meinhof (the splendid Martina Gedeck), not yet having burned her bridges and thrown in with the Gang, with the challenge: “Do you think your theoretical masturbation will change anything?” When Ensslin proclaims, “We need a new morality,” what she means is more like no morality at all.

But the relative verisimilitude of Complex conceals its deficiency, which is the deficiency shared by its entire genre of action-history film. It suffers from the reductive quality that Arthur Miller once described to me as the “simple recognition of reality,” which is characteristic of naturalism. The student movement is brutally set on by the police. (True.) Some of the movement’s outliers resolve on “action.” By “action,” they mean violence. No alternative is proposed. The student movement is the gateway drug. What gives the movie its momentum is its sense of inevitability, for once they are launched on their course, Baader, Meinhof, and the rest are stick-figures of the Zeitgeist, not choosing human beings. They purport to be doing politics but they are doing Triumph of the Will, the absence of politics. Nobody on screen seems ever to have thought that anything could be accomplished by civil disobedience, or by any other means of changing the world besides shooting it up.

But this is only to say that the reality of Baader-Meinhof, hallucinatory as it was, was built on a delusion shared by many—that the vast crimes of the recent German past could be purged with effusions of terror and could not be purged in any other manner. The film can’t be faulted for depicting them in all their crudity. At one point, as the smart police official (played by an underutilized Bruno Ganz) says, according to a respectable poll, a quarter of West Germans under 40 said they felt “a certain sympathy” with the Gang; one in ten said they would be willing to hide one of the gang from the cops. “We must change conditions,” he says, in a sort of self-parody of liberal hand-wringing. In truth, the Gang was destroyed without global reforms—though it took years after the Vietnam War ended. At another point the Ganz character declares that what motivates Baader-Meinhof is “a myth.” The contradiction doesn’t strike him—or anyone else in the film. The movie, almost as tedious as it is breathless, moves on to the next kinetic moment.

Todd Gitlin, a onetime president of Students for a Democratic Society who teaches at Columbia University, is the author of 12 books, including The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage.

Todd Gitlin (1943-2022), was a professor of journalism and sociology and chair of the Ph.D. program in Communications at Columbia University, and the author of among other books The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage; Occupy Nation: The Roots, the Spirit, and the Promise of Occupy Wall Street; and, with Liel Leibovitz, The Chosen Peoples: America, Israel, and the Ordeals of Divine Election.