Miriam Michelson, American Jewish Feminist Literary Star of the Western Frontier

(And her brother Albert won the Nobel Prize in Physics)

Abandoned by her off-the-derech Hasidic mother, Rebekah Roberts, the semi-autobiographical journalist-sleuth of reporter Julia Dahl’s Invisible City, published by Minotaur Books this past May, has little knowledge of her Jewish heritage, beyond the Hebraic spelling of her given name. So, when the rookie reporter is sent to investigate a murder in Brooklyn’s Hasidic enclave, she sees the assignment as a dual opportunity: Scoop the rival tabloids with an exclusive on the slain mother of four, whose naked body had been found in a Gowanus scrap heap, and reconnect with her own mother, who returned to the Haredi, or ultra-Orthodox, fold after her daughter’s birth, leaving Rebekah to be raised by her Christian father in Florida.

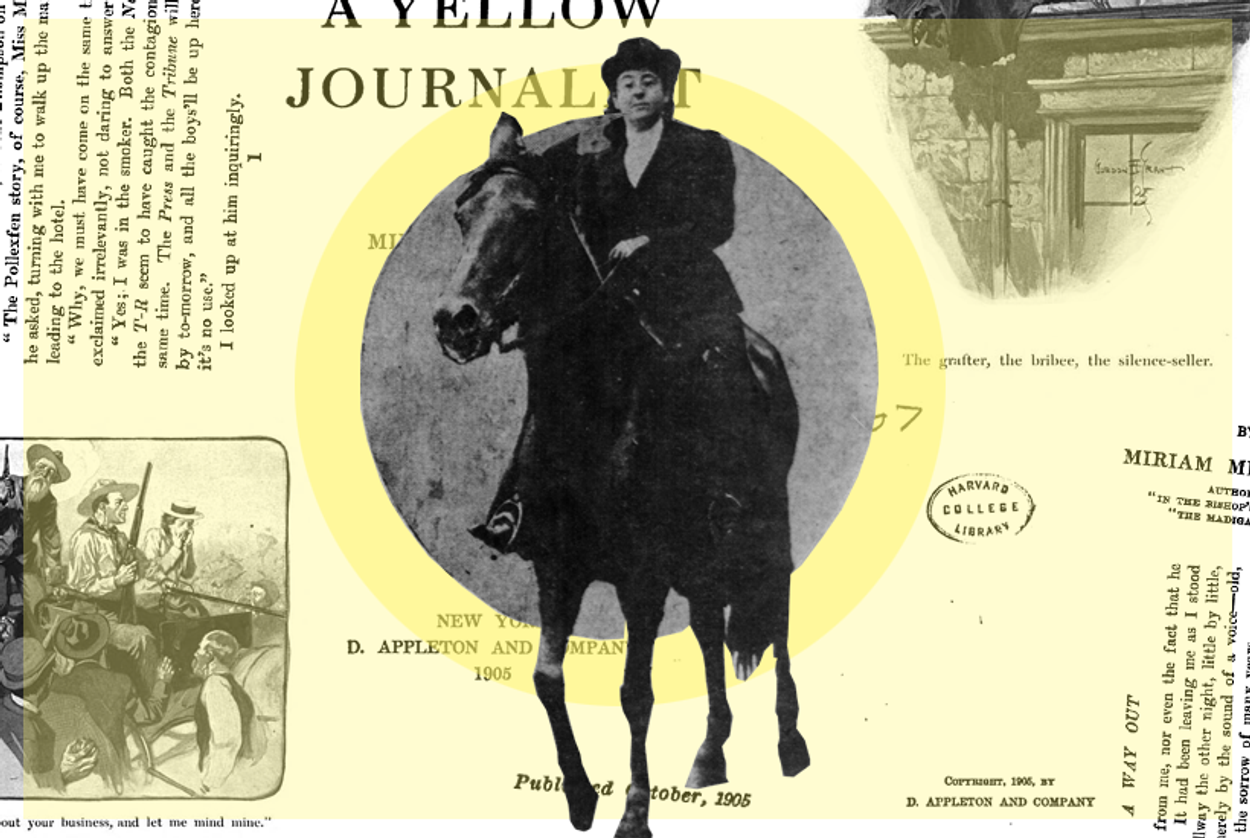

Over a century before Dahl, another Jewish writer turned her own sensational experiences as a newspaperwoman into a suspense-filled, bold-voiced work of popular fiction. The writer’s name was Miriam Michelson, and the novel, A Yellow Journalist, published in 1905, began as a series of short stories in The Saturday Evening Post. These interlocking stories chronicled the adventures of the author’s gutsy alter ego, Rhoda Massey, a “girl reporter” for a San Francisco newspaper in the time of Hearst and Pulitzer.

If you’ve never heard of Michelson, you’re far from alone. Neither had Dahl (we checked), despite the uncanny resemblances between these two reporters-turned-fiction writers, both unaffiliated-but-Jewish-by-birth California natives. Nor, we’ve discovered, have most scholars of American literature, even those who specialize in recovering forgotten texts by Jewish American and women writers.

If Michelson enters into the historical record at all, it’s as no more than a footnote in the story of her brother, physicist Albert Abraham Michelson, who, in 1907, became the nation’s first Nobel Laureate in the sciences for, among other discoveries, inventing the interferometer, a device that was used in experiments to measure the speed of light. (She’s absent, too, from the 1962 episode of Bonanza titled “Look to the Stars,” which fictionalized Albert’s confrontations with anti-Semitism as a schoolboy-genius in Virginia City, Nev.)

At the turn of the 20th century, however, Miriam Michelson was a feminist force to be reckoned with. She was a brazen, liberated woman who broke gender barriers in the journalistic profession, covering crime and politics for San Francisco’s top dailies throughout the 1890s, a decade that relegated most female reporters to the soft news of the so-called “Woman’s Page.” She went on to become one of the early 20th century’s most commercially successful fiction writers, supporting herself by publishing short stories in a range of mass circulation magazines, including Century, Ainslee’s, The Smart Set, and the Ladies’ Home Journal. Throughout Michelson’s 40-year career, her interest remained with the imaginary adventures of audacious women making it on their own, characters who anticipated Dahl’s Rebekah Roberts (who resents her boyfriend’s meddling attempts to protect her) as well as the chick-lit creations of Lauren Weisberger and Jennifer Weiner (though, in comparison, Michelson’s women are refreshingly free of angst).

Michelson’s first novel, In the Bishop’s Carriage, published in 1904, featured a female pickpocket as its first-person protagonist. The scandalous appeal of this picaresque novel made it an instant best-seller, a book so popular that it was dramatized for the stage by director Channing Pollack in 1907 and subsequently became the basis of two Hollywood films: the first, in 1913, a vehicle for the “sweetheart” of the silents, Mary Pickford, and the second, in 1920, renamed She Couldn’t Help It, with former child star Bebe Daniels in the leading role of streetwise petty thief.

As Michelson became a nationally renowned writer, she was also recognized as a famous Jew. Though the first-generation American insisted on her secularism, telling her brother’s biographer that she “had no religious training whatever,” the national press often took note of her ethno-religious background, and the Jewish press regarded her as one of their own. As The American Israelite proudly announced, “Miriam Michelson, a brilliant young newspaper writer and novelist who came out of the west a few years ago, has taken her place among the leaders of contemporaneous fiction.”

But why has Michelson remained so long in obscurity? The answer lies partially in the conflation of early Jewish literary production in the United States with the ghetto tale—the stories of immigration and assimilation penned by writers such as Abraham Cahan, as well as Anzia Yezierska and Mary Antin. Every reader of Jewish American literature is familiar with this well-worn narrative, in which the yearning, striving greenhorn Americanizes, trading the name Yekl for Jake or Mashke for Mary, abandoning beard and sheitel, and dreaming, Horatio Alger-style, of the rise from factory floor to the Fifth Avenue mansion.

What most readers of Jewish American fiction don’t know is that at the same time that immigrants such as Cahan were mining the pushcarts and sweatshops of the Lower East Side for material, another group of Jewish writers, most of them women, were producing writing set in the towns and cities of the Western frontier. Michelson’s female reporters, for instance, chase stories from the foothills of the Sierra Nevadas to the brothels and gambling dens of San Francisco’s Chinatown. Her heroines’ speech is breezy and slangy—a marked contrast to the Yiddish-inflected dialect that was the hallmark of the ghetto storytellers. While occasional Jews do appear in her stories—sometimes, but not always, conforming to “type”—Michelson also populated her fiction with Irish, black, Chinese, Hawaiian, and Native American characters. Her work testifies to the ways that Jewish writers captured the regional and ethno-racial diversity of American life and were engaged with cultures and traditions other than their own—an aspect of Jewish literary history easily forgotten among the New York ghetto tales that make up the turn-of-the-20th-century canon.

Michelson was herself a product of the 19th-century multiethnic West. She was born in 1870 to Polish immigrants Samuel and Rosalie (Przylubska) Michelson, who had fled anti-Semitic persecution in their hometown of Strzelno. In 1854, Samuel and Rosalie landed at New York, initially living, like many of their co-religionists, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Lured by news of the Gold Rush, they headed West and eventually settled in the boomtown of Virginia City, Nev., where they prospered as merchants, selling supplies to miners and raising seven children. (In addition to future Nobel Laureate Albert, Miriam’s siblings included Charles Michelson, a reporter and newspaper editor who went on to become the first publicity director of the Democratic National Committee under FDR.)

Known best as the domain of Mark Twain’s early writings, Virginia City figures prominently in Michelson’s second, admittedly autobiographical novel, The Madigans (1904), a devilish romp about a sextet of trouble-making sisters, and is the subject of her only full-length work of nonfiction, The Wonderlode of Silver and Gold (1934), a history of Comstock mining with bits of memoir thrown in.

While Michelson’s unconventional background makes her an outlier among her contemporary Jewish American writers, her immense popularity also contributed to her disappearance from the annals of literary history. Though Jack London, Stephen Crane, and other male writers who published alongside her in mass-circulation magazines have secured their places in the literary canon, Michelson’s work was viewed as ephemeral and faddish, worth attention mostly because of its entertainment value. Influential critic H.L. Mencken openly admired the “ingenious” twists and turns of the “identical twin” plot in her 1909 novel, Michael Thwaites’s Wife, but failed to pick up on the complexity of Michelson’s feminist undercurrents and radical dismissal of the sanctity of marriage, describing the book as “a literary joy ride.” In a review of A Yellow Journalist, the Atlantic Monthly similarly acknowledged the “breathless” excitement of “scurry[ing] along on a ‘beat’ ” with reporter Rhoda Massey, even if the reviewer’s conclusion that “Miss Michelson is as popular, as ‘catchy’ as ragtime” turned out to be damning praise.

As a whole, Michelson’s oeuvre defies easy categorization. By the time of her death in 1942, she had produced a wide variety of fiction, experimenting with a range of genres from science fiction to historical romance. Her 1912 novella, The Superwoman, for instance, offered a trailblazing feminist vision of a matriarchal utopia, while her last novel, The Petticoat King, published in 1929, was based on the life of Queen Elizabeth I. In her nonfiction writing, too, Michelson addressed a host of women’s issues, including suffrage, dress reform, and the economic status of wives (they were, in her words, “eternal beggars”).

In her classic essay “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” novelist Alice Walker wrote of the struggle for black women writers to find their literary foremothers and the need to forge innovative creations in the absence of lasting artistic models from the past. Michelson’s productivity and commercial success suggest that Jewish women’s voices were given an opportunity to flourish in America, that they were not subjected to the racism and sexual oppression that silenced so many of Walker’s foremothers. Yet, as is the case for most women writers, whatever their background, Michelson’s work was deemed unworthy of preservation. There are no—at least to our knowledge—manuscripts saved and papers carefully archived.

And so we continue to search for this Jewish feminist foremother, tending our own literary garden, hoping that the too narrowly defined Jewish American canon will find room to grow.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Karen E. H. Skinazi and Lori Harrison-Kahan hold doctorate degrees in English with specializations in American literature. Their scholarly introduction to Miriam Michelson and her work is forthcoming in the journal MELUS (Multi-ethnic Literature of the United States) and will be accompanied by a reprint of a chapter from A Yellow Journalist (1905).

Karen E. H. Skinazi and Lori Harrison-Kahan hold doctorate degrees in English with specializations in American literature. Their scholarly introduction to Miriam Michelson and her work is forthcoming in the journal MELUS (Multi-ethnic Literature of the United States) and will be accompanied by a reprint of a chapter from A Yellow Journalist (1905).