My Harold Rosenberg: Saul Bellow Fictionalized My Love Affair—Now Here’s My Version

Three decades after Saul Bellow fictionalized my love affair with the great art critic, it’s time for my version

In 1984, a friend from East Hampton phoned me in my New York City apartment.

“Joan! I didn’t know you had an affair with Harold Rosenberg.”

“What are you talking about?” She wasn’t a close friend.

“I just heard that Saul Bellow has a story about Harold and you in the new Vanity Fair.”

“Saul Bellow has written what?”

As we spoke, phone in one hand, the other hand stretching my tangled phone cord to near breaking point, I grabbed any clothes I could find. After saying goodbye, I looked up the address of Vanity Fair’s Midtown office, dressed, ran a comb through my hair, and raced out the door to the subway.

Barging into the magazine’s office, I confronted the first person I saw. “You’ve got to give me a copy of your new issue. Saul Bellow has a story in it about me! If I don’t get it right now, I’ll have to consult my lawyer.”

I suffered through the next 10 minutes, watching the woman I’d verbally accosted huddle with two other women around a large L-shaped desk. Then she rushed me back out through the door into the hallway.

I all but grabbed the large manila envelope from her hands. Inside, in blocky gold letters on a lush red heart, Vanity Fair’s new “Valentine” issue, proclaimed: “Extraordinary Love Story by Nobel Prize Winner Saul Bellow.”

Thankfully, neither the cover, the story’s title, “What Kind of Day Did You Have?” or its description, “a high-flying story of a down-to-earth romance between a zaftig young Chicago matron and ‘a world class intellectual of seventy,’ ” was an instant clue to Harold’s identity—or to mine. But people in the art and literary worlds wouldn’t need to read far to realize that the story’s protagonist, “Victor Wulpy”—a “huge, physically imposing man, big in the art world”—had to be Harold.

Few of the same readers would recognize the real-life model for the story’s love-stricken heroine, “Katrina Goliger.” But despite his fictionalization, many of my friends would know that Bellow had based Katrina on me: “Dumpy … Dumb Dora … divorced … suburban matron … confused sexpot … passably pretty … (with) varicose veins and piano legs.”

It wasn’t only Bellow’s physical description of me that rankled. Harold had counted on me to behave with total discretion about our relationship. Back home, I skimmed the novella a second time, then phoned my lawyer, asking if I had grounds to sue.

“Don’t sue,” my lawyer said. “You’ll just attract more publicity.”

I feared he was right. Publicity was the last thing either I or my four adult children would wish. They had already suffered enough from my overpowering obsession with Harold, and from my protracted divorce from my husband, without my subjecting them to unasked-for publicity. Squelching my guilt, I wrote to “my author/creator.” I described to Bellow my dismay finding my largely secret affair with Harold made public and my mortification at the depiction of me—to which he responded that I should be flattered to be in any story of his.

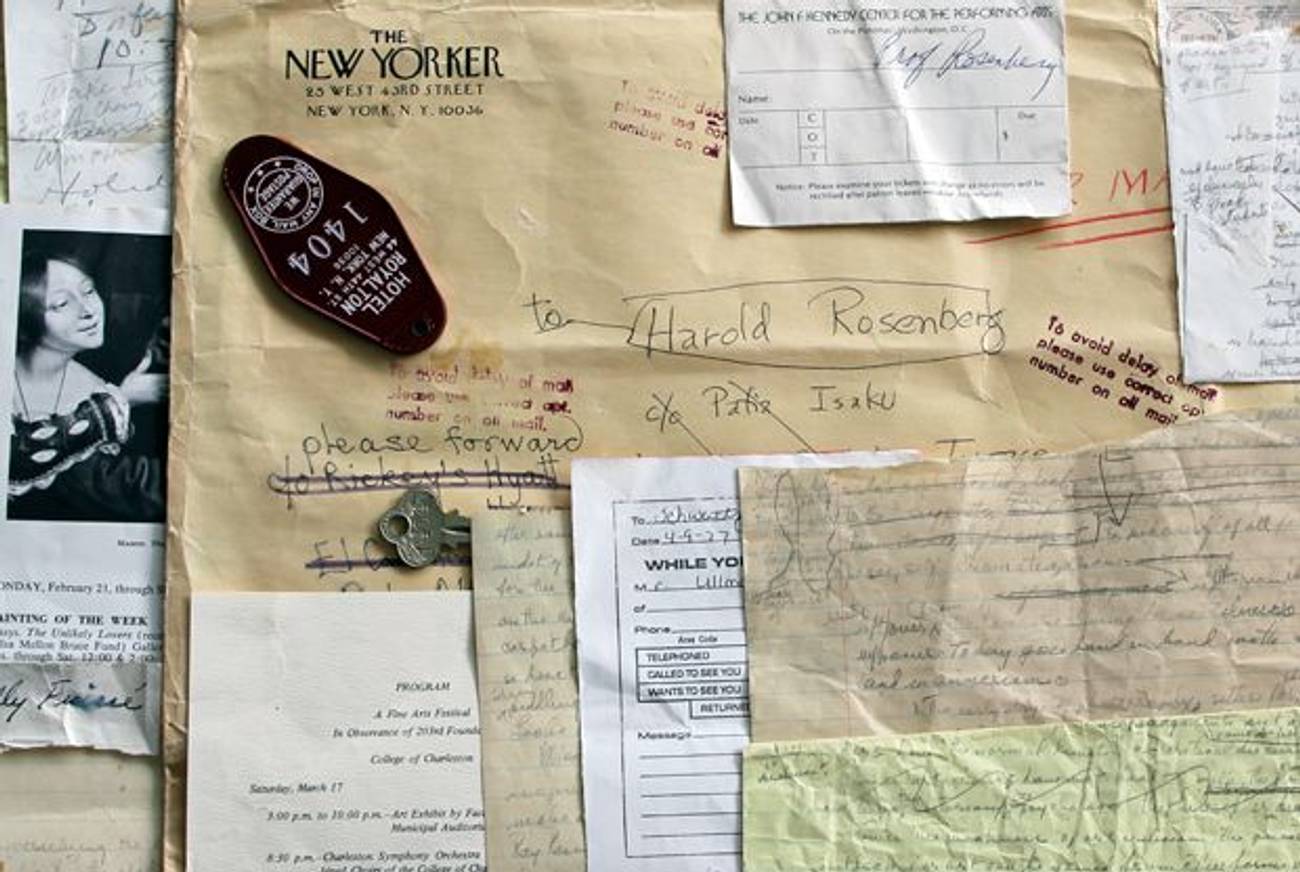

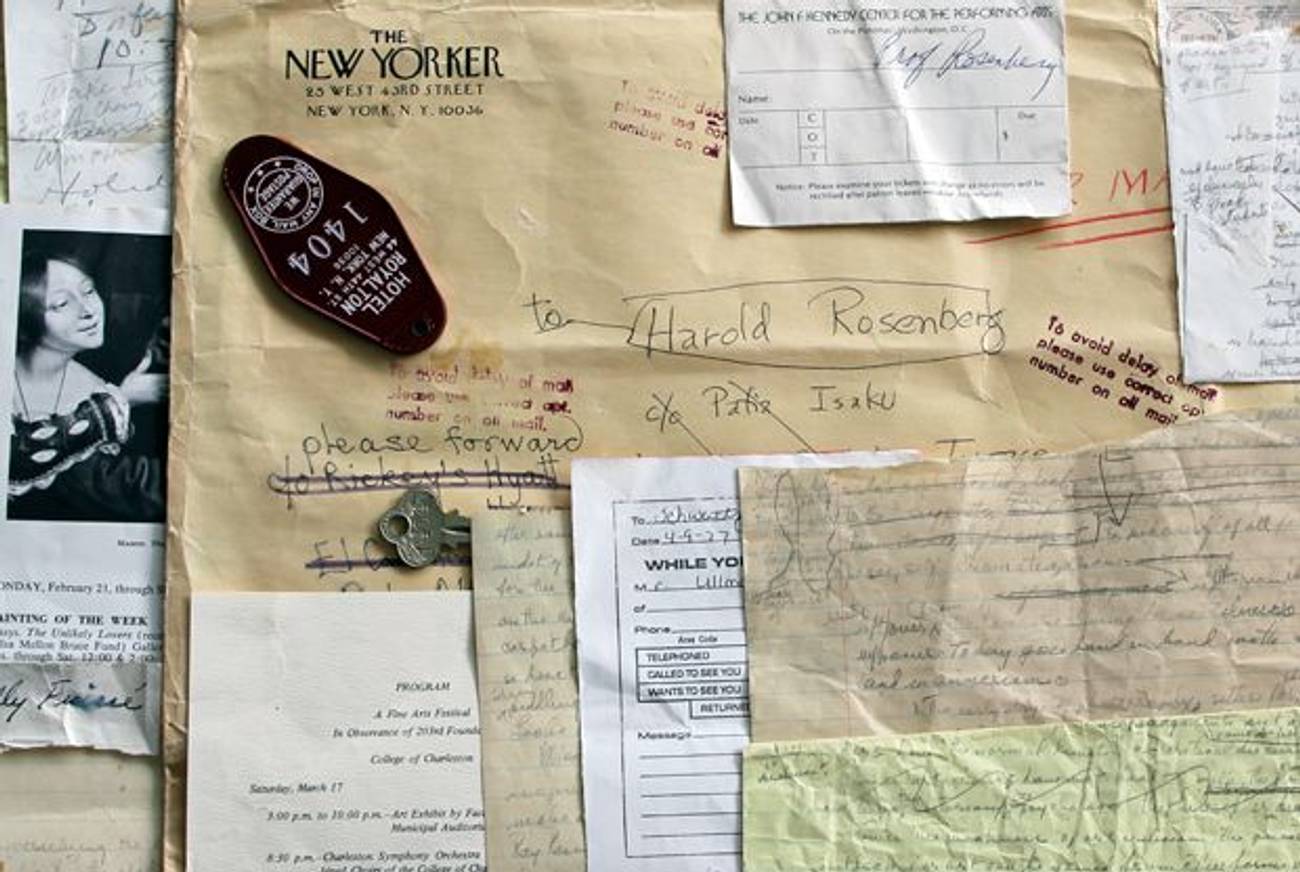

That answer never satisfied me. Bellow had pillaged key incidents from my life, which should have been mine to tell. But for years I never did. I knew that my behavior was indefensible and irresponsible, but I also believe the affair was part of who I was—and had made me into the person I continued to be. I saved every scrap from our time together: Harold’s brief letters to me; handwritten notes for his articles he’d jotted on invitations, envelopes, or whatever paper he could scrounge; keys and receipts for our $14-a-day hotel rooms, as well as for my round-trip air flights and long-distance phone bills. It’s only been recently, as I neared the end of my intermittently worked-on memoir about Harold and began writing this essay, that for the first time the true cost—the steep price I’d paid to be with Harold—struck home.

***

Many people assumed that Harold Rosenberg owed his invitation to lecture at the University of Chicago to Saul Bellow, but my family knew better. We knew it was my mother-in-law, Duffy Schwartz, who was responsible for bringing Harold to Chicago. She and Harold had worked for the public-information-dispensing Advertising Council for years: he part-time in Manhattan, she in Chicago. For months, she’d also alerted us to each new article of Harold’s published in Vogue or The New Yorker. But that Sunday night in 1965, after dinner in my in-laws’ glassed-in sun porch, Duffy’s mention of Harold’s name precipitated an immediate family quarrel.

“You remember Harold Rosenberg, don’t you, Charlie?” she asked. “I sent you to ask him for advice about finding work in New York after you finished law school.”

“Oh, Mother,” my husband said. “Harold asked if my ‘Mama’ had sent me! I had nothing to ask, and he had nothing to say.”

“Charlie!” Duffy said. “Everyone at the Council agrees that Harold’s advice on any subject is invaluable.”

“Are you telling us that your friend Harold is the unsung genius behind ‘Smoky the Bear,’ or ‘Buckle Up For Safety’ and your other public safety slogans?”

“You know, we all contribute,” my mother-in-law said. “But now, after years of my suggesting it, he’s finally going to lecture at the university.”

At the time, I knew nothing of Harold’s reputation and hadn’t read anything by him. With three children under the age of 8, a fourth on the way, and a part-time job at the university writing abstracts of business articles about the psychology of economics, marketing, and labor, I felt lucky to finish an occasional Agatha Christie mystery. It was my friend and neighbor, the painter Vera Klement, who explained the reasons for Harold’s renown one afternoon after we’d picked up our sons from kindergarten. Vera told me that he’d coined the term “Action Painting”—a recognition that art’s true essence lay in the process of creation, not in the finished product. She defined that process as the drama touched off when an artist puts his or her brush to canvas, or when, like Jackson Pollock, he hurls or lets the paint drip or splatter down onto the canvas from an outstretched arm. Harold’s insight had helped create interest in works by Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Marc Rothko, and other soon-to-be-famous Abstract Expressionists.

That night, I told Charlie what I’d learned. “What’s the problem?” he asked, from amid the mountainous stacks of newspapers, magazines, articles, and other clutter that took up most of his office. “You still end up buying the canvas, not the artist.”

That Friday evening, on entering the auditorium with my in-laws—Charlie had refused to miss the chamber music concert for which we had tickets that night—I glimpsed Hans Morgenthau and Bruno Bettelheim—some of the university’s Jewish European refugees on the faculty.

I sat and readied myself (or braced) for the talk. Lectures about art typically left me glassy-eyed. But suddenly, there stood Harold. A ruddy-cheeked colossus, in his mid-60s, he radiated the youth and vigor of a man half his age. He began by rattling-off names: Pollock, de Kooning, Rothko, Franz Kline. But he didn’t discuss specific techniques or paintings. He reminisced about his friendships with the artists—of having stood in their studios, witnessing the struggles that had shaped their creations. He described the dancing parties in their Greenwich Village lofts, their drinking and debating at the Artists’ Club and Cedar Bar, the playfulness in the early years of their softball games in East Hampton. Wave after wave of laughter swept the room. “Now, that’s real art history I’m giving you tonight,” Harold said, wiping tears of laughter from his own eyes.

His talk expanded to cover the uneasy relationship between the avant-garde, museums, and corporations; the merging of high art and low; the co-opting of the avant-garde by the bourgeoisie. “What should the consumer make of it all?” he asked, ticking off today’s mushrooming styles: Pop, Op, Hard Edge, Minimalist, etc.

I realized I was listening to a multilayered social commentary that was witty, profound, and ironic—unlike any I’d heard before. Harold’s talk also made me realize what I’d missed since graduating from Radcliffe. Charlie liked ideas. But he wanted ideas to behave like well-trained dogs: They should be tightly leashed, trained to sit and heel, whipped for straying too far. But Harold reveled in ideas that acted like dogs unleashed on the beach—who rolled on the sand, who swam and roamed the farthest.

The lecture ended in a din of applause. Duffy maneuvered us through the crowd up to the podium. After congratulating Harold on his talk, she said, “I want you to meet our daughter-in-law, Joan. You know, Charlie’s wife.”

Black eyes gleaming, Harold seized hold of my hand, “Oh, so you’re the famous daughter-in-law!”

“I hate to think what you’ve heard,” I said, blushing at sounding so inane.

“Come on, Charles, Joan,” Duffy said. With that, she grabbed my father-in-law and me each by an arm and rushed the three of us through the auditorium to the door.

***

The following year, in 1966, along with being named The New Yorker magazine’s art critic, Harold became a full professor in the University of Chicago. He was sometimes accompanied by his imposing wife, May, but spent most of his time in the city alone. His faculty appointment gave my life a new focus. Charlie and I hosted, or were guests at, parties given for him. I chauffeured, ran errands for Harold, audited his classes, attended his lectures. Before rapt audiences of any size, Harold held forth on topics ranging from the pettifoggery of Clement Greenberg and other art critics, to the motivations of Hamlet, to “that putz” Nixon and that other “putz” Henry Kissinger.

Occasionally, on my way home from my abstract-writing job at the Industrial Relations Center, I’d drop in on him unannounced at his campus office and listen to him orate in private. During one visit, he told me why he required a cane—the gnarled, shellacked brown-and-black walking stick that was his constant companion. Harold had been 22, and about to begin his law practice, when he contracted osteomylitis—a deadly bone infection—in his right leg. A surgeon had saved his leg from amputation, though at the cost of fusing his femur to his kneecap, keeping the leg permanently rigid. It was during his long recuperation that he began to publish.

“Of course the leg adds to my appeal,” Harold joked. “I’m tall, dark, handsome, and a poet. And I’ve got this wound. What woman could resist all that?” During my various encounters with Harold, he’d also suggest—sounding like Mae West—“you ought to come around some time.”

I didn’t take Harold’s mock flirtation seriously. But I was becoming increasingly preoccupied with him, counting the days until I’d see him again. One late November afternoon, as we stood near the door to his office, he said again, “You really should come around.” I stopped and I stared boldly into his eyes. “When?”

With Harold’s fall teaching quarter ending, however, we opted to defer our affair until spring. By asking “When?” I had hoped to make clear that I was up to beginning an involvement. I wasn’t sure if I felt more relieved than frustrated that it would have to wait.

“I’ll miss you,” I said, still standing at his office door. “Please write me.”

“You know me, Ullman. I’m always swamped in mail. I’ll write when I can.” Tugging on a strand of my hair that had pulled loose from my ponytail, he added, “You write me, though.”

“How often?”

“I don’t know. Wreck the family fortune on stationery! Write every day, if you like.”

Within a few weeks, waiting for the mail became as much a routine in my life as waking the children, fixing their breakfast, and readying them for school. In every spare moment, I’d retreat to my bedroom, pull down the top of our teak Scandinavian desk, seize my red ballpoint Parker pen, and fill Harold in on the Hyde Park goings-on. Nine days after we’d said goodbye, and after dozens of letters I’d mailed to his office, I spotted a tiny, cream-colored envelope with its New Yorker emblem, addressed to me.

“New York’s gone quiet this Dec.,” he wrote. “Like Hickey said—‘Someone’s spoiled the booze.’ I do think of you though. But don’t get your hopes up, Ullman. Always too busy for missing. Love, H.”

I sat on our hallway chair, trying to pierce beneath his words. Did he miss me more than he admitted? Was this why he felt New York had lost its fizz?

I realized that, in the deluge of his letters, I was becoming obsessed with being his mistress. I’d never been a mistress before, or devoted any thought to being one, and the obstacles confronting me at that time were overwhelming: his fame; his known attraction to liquor; his age, nearly twice that of mine; his reputed womanizing but staunch aversion to divorce; his health, visibly shaky, given his worsening arthritis, gout, and stomach ailments—even his vaunted sexual prowess was undergoing, in his words, “a perceptible decline.” As a married mother of four young children, in the University of Chicago neighborhood, my obsessing about becoming a mistress would seem to have been totally out of keeping with any expected concerns. But I was swept away; I gave no thought to propriety.

That spring, when we finally lay entwined on the Murphy bed in his Windemere Hotel room in Chicago, I said the words to Harold. “I would rather be your mistress than Charlie’s wife.”

Harold’s look of alarm was unmistakable. “In Europe, where divorce was frowned on, keeping a mistress may still make some sense. But in America,” he said, “the business with ‘mistresses’ has been reduced to farce. There are wives, ex-wives, new younger wives. But a mistress in mid-century America is as obsolete as the novel.”

I was not convinced. We were still a thrilling tangle of limbs, hair, and tongues. “I adore you,” I said, determined to overcome Harold’s resistance. “And I adore you,” he said. But I did understand what Harold meant when he dismissed the concept of a mistress as an antiquated notion. The term conjured an image of an old-fashioned, beautiful, kept woman—a courtesan, like the heroine in La Traviata, La Bohème, or Manon, who is destined for a tragic end. I also viewed the word mistress as shorthand for the role of a woman in an illicit, extramarital relationship with a married lover, a situation whose descriptive words alone carry a whiff of criminality: sneaking off, stealing away for a few furtive hours alone with one’s lover.

But for me, getting Harold to call me his mistress became synonymous with getting him to say “I love you.” Frustrated as I was by his continuing resistance, I never took Harold’s refusal all that seriously. By my logic, it was in my husband Charlie’s presence that I felt unloved, whereas whenever I was with Harold, I basked in feeling totally accepted for who I was—and consequently totally loved.

One day in early 1970, as Harold and I flew from Boston back to Chicago, our cabin had filled with smoke. The upper compartments flew open, releasing orange-yellow-colored oxygen masks, dangling down on their cords. My mouth went dry as I pictured the headline: “Famous Action Painter Critic Dies in Plane Crash With Hyde Park Mother of Four.” That morning, no one in my family knew I’d been in Boston overnight.

“Won’t you at least say you love me now?” I’d forced out the words through parched lips. Harold didn’t answer; his own oxygen mask was already fixed to the lower part of his face.

***

In late 1970, Charlie and I finally got divorced. He had learned about Harold and me after discovering my letters from Harold in the drawer where I’d hidden them—which he then Xeroxed should he need them in court. I was distraught over his finding the letters and terrified lest he publicize my relationship with Harold.

After my divorce, I sometimes spent two or three nights with Harold when he was lecturing. I journeyed to gorgeous parts of the country—Atlanta, Santa Barbara, Chapel Hill—but I saw almost nothing of their beautiful sights. Lounging with Harold indoors or outside on a motel room’s patio over breakfast felt like paradise. Then he’d leave for his luncheon, lecture, parties, while I lay in bed and tried to read. I’d turn the TV on, then off, and back on again. But I couldn’t concentrate. I’d worry: Was my oldest son finishing his homework? Were he and my younger son fighting again? Just when I’d be at my most tearful and guilt-ridden, the door would open.

“How did it go? How are you feeling?” I’d ask.

I’d cover him in kisses, then fling myself on top of him on the bed, pulling at his heavy brown oxfords, helping him remove them.

I lived on hope—that he’d remain healthy, that I’d see him again in two, at most, in three more weeks. When making my way through the aisles of a supermarket, one hand pushing a grocery cart for Harold, the other a cart for my family, I knew I was leading a double life. I’d come to an item on Harold’s shopping list—eggs, mustard, blood sausage, pearl onions for his martinis—and I’d stop. I’d study each price, to be sure of picking the cheapest brand for the money. When I wasn’t mulling the prices on Harold’s list, I’d race down the aisles as usual, tossing item after item into the cart for my family so I could finish their shopping as soon as possible. Occasionally, when Harold encountered friends on the street, he’d stop to chat, while I’d stand mutely by his side. After a while, he’d sometimes say, “This is Mrs. Ullman.”

But eventually I began to fear that rather than leading a double life, all my waiting around indoors hoping for a phone call from Harold, which deprived my children so many activities—taking them shopping, for walks, to the playground, to the movies—meant I was really leading half a life.

***

After Harold’s death in 1978, I spent years mourning his loss. Unable to occupy myself with the limitless chores that consume the time of a bona fide widow—choosing the form and place of burial, planning a funeral, memorial or both, ordering flowers—I roamed the Manhattan streets where we’d spent time. I’d look in the windows of the Emigrant Savings Bank on Madison and 43rd, one of at least half a dozen banks in which Harold had opened accounts in the 1970s to avail himself of the toasters, electric blankets, and other freebies that New York banks were giving away to attract new customers. (He ceased this practice not from a glut of electric blankets, but because one day he couldn’t remember the locations of his most recently acquired accounts.) Roaming the streets was how I mourned.

Bellow’s Vanity Fair novella, published six years after Harold’s death, plunged me into a new bout of grief—not simply because he revealed a secret of mine, but because it forced me to realize that the story wasn’t only about Harold and me. Like any fiction writer, Bellow had transformed his raw material. He’d added characters and subplots I didn’t recognize, doubtless drawing on his own experiences, or those of other people in his life. I wouldn’t have recognized Bellow’s depiction of our nearly fatal plane trip from Boston if he hadn’t put Harold’s refusal to tell me that he loved me at his story’s core.

Nevertheless, Bellow had also managed to recreate—or resurrect—a remarkable likeness of the man I’d adored. And if aspects of the Rosenberg/Wulpy character owed at least as much to Bellow as to Harold, I still felt more awe than anger toward the writer who’d breathed such life into this fictional creation. But Bellow wasn’t present a few nights before Harold died, when he seized my hand in his hospital room and said, “There are two things I care about. My work, of course, and you.” Coming from this guilt-ridden man—a self-styled bohemian, who’d espoused what he’d termed “the tradition of the new” but had lived by a more Victorian “tradition of the old”—credo, “one wife, many women”—those words in Harold’s final days meant everything to me.

Eventually, I formed a new relationship and spent more than two decades as a journalist writing about high-profile trials. Intermittently, however, I struggled with writing a memoir. I tried to retrieve pieces of Harold that had seemed to have vanished: the gentle tug of his hand on my hair; his tough, street language—“in a pig’s ass,” “you’re a dead dog,”—words I once thought of as hip but that would make today’s more enlightened generations brand him a male chauvinist pig. Above all, I struggled to make sense of my overwhelming obsession. Initially I couldn’t fathom my own behavior at all. It seemed so insane. It was as if I’d acted on automatic pilot, doing anything just to be near him—for those few heady moments when I felt totally safe to be myself and to feel totally accepted for who I was. Such moments in life are rare and fleeting, which is why I still can’t manage to regret my time with Harold. But I’m left with new questions about the choices I made. What I hope to recapture now, at this late stage of my life, is the clarity that I abandoned for the man that I loved.

Joan Ullman, a New York-based freelance writer and psychologist, has appeared in, among other publications, The New York Times, Elle, Psychology Today, and the New York Observer. She is completing a memoir about Harold Rosenberg.