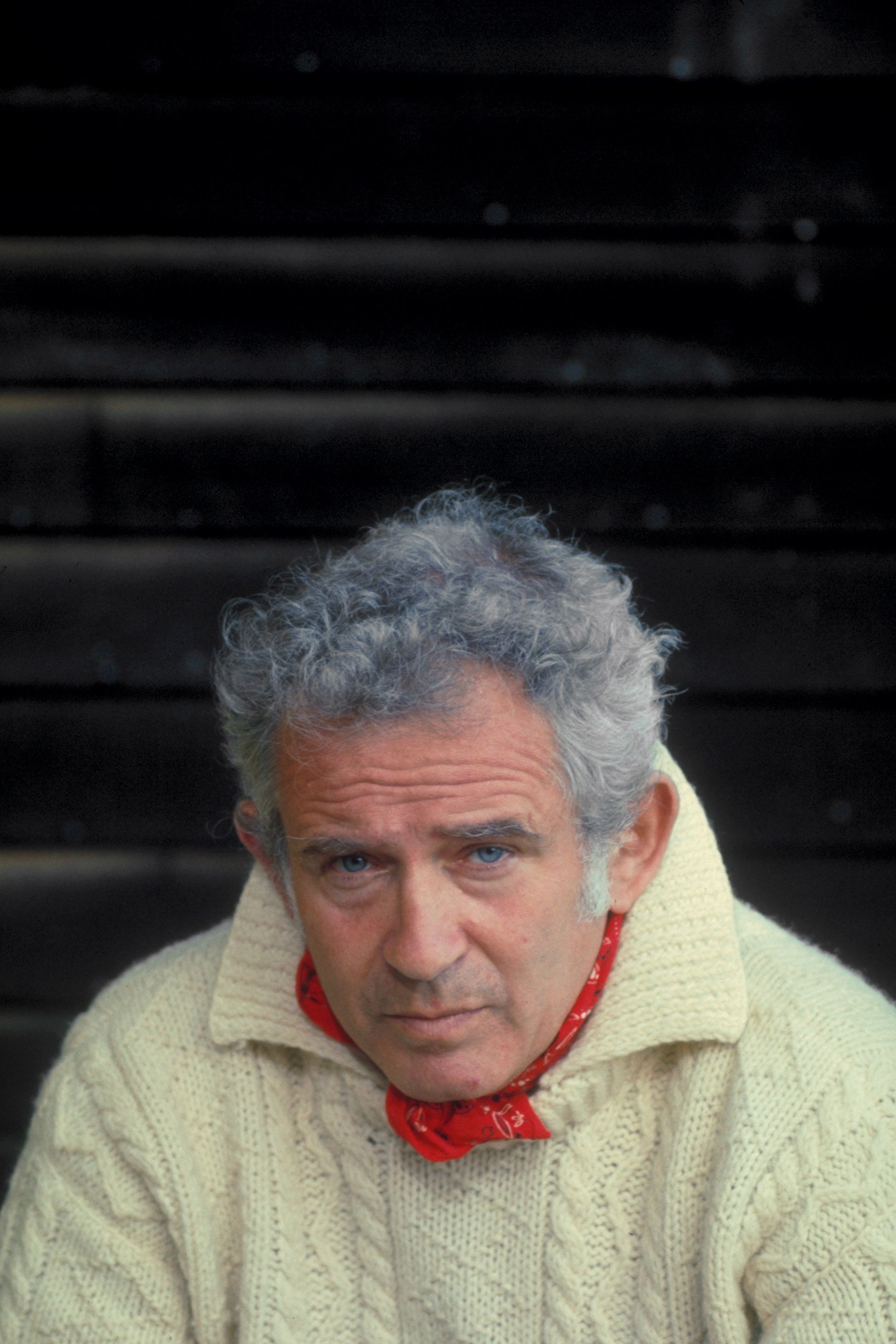

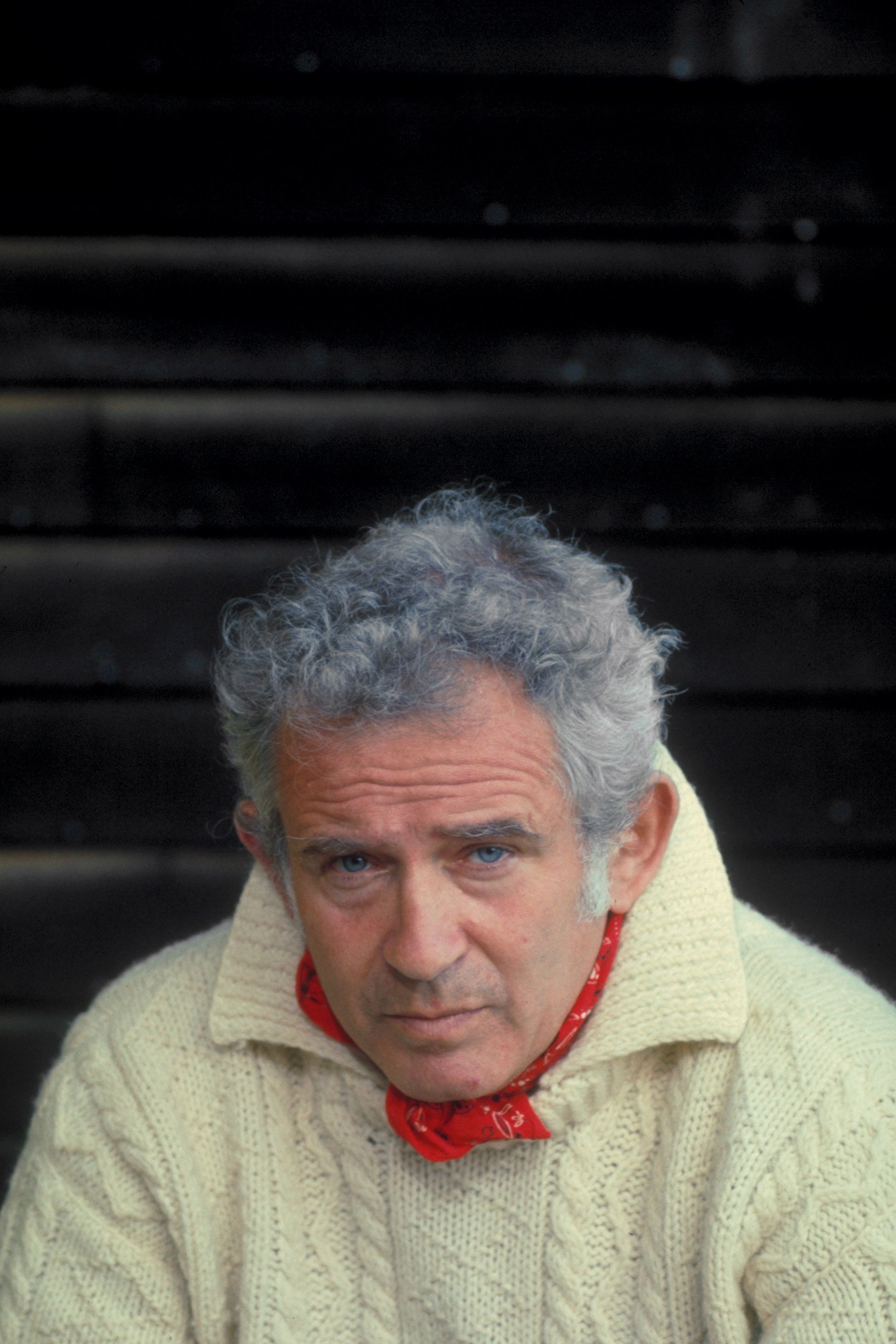

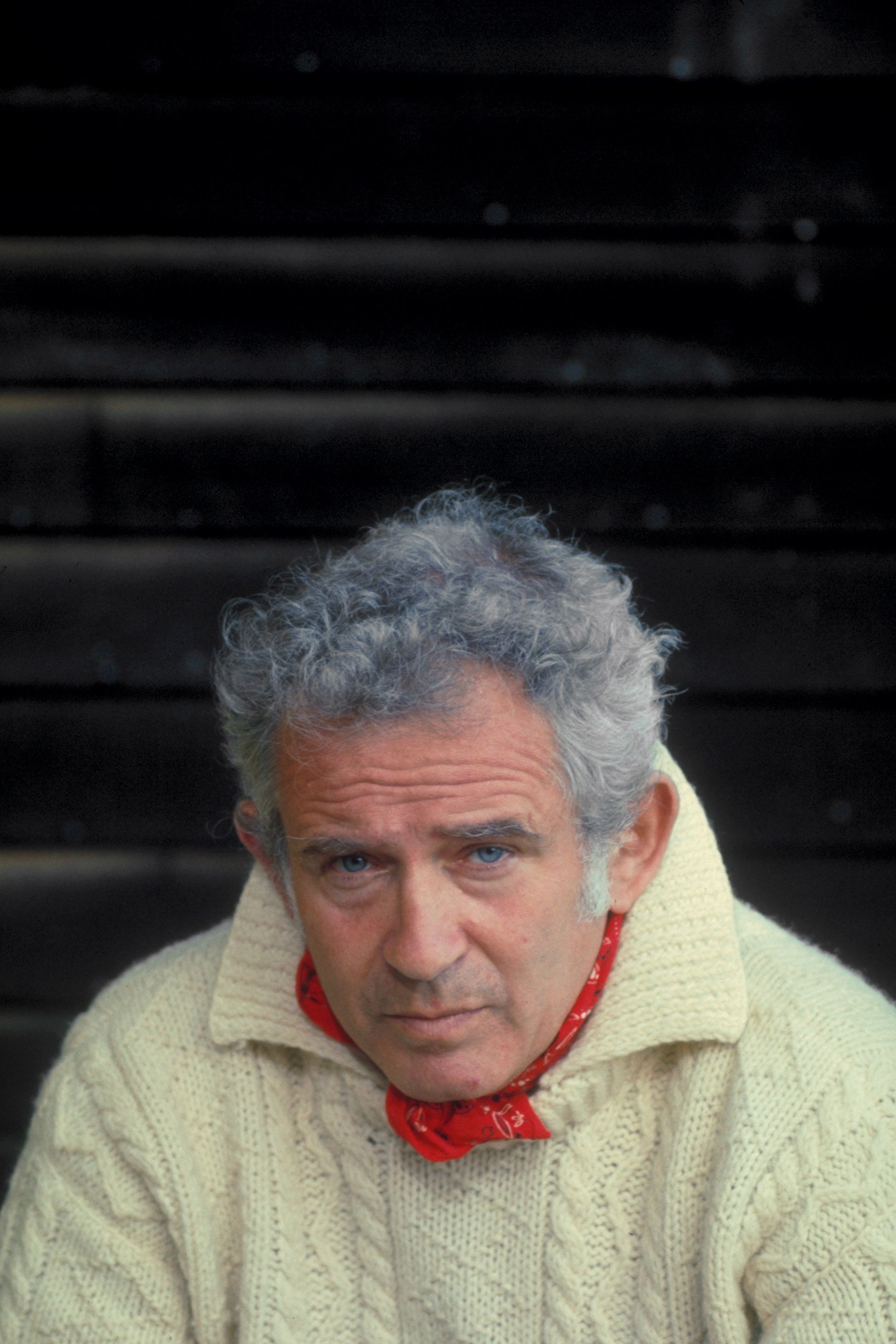

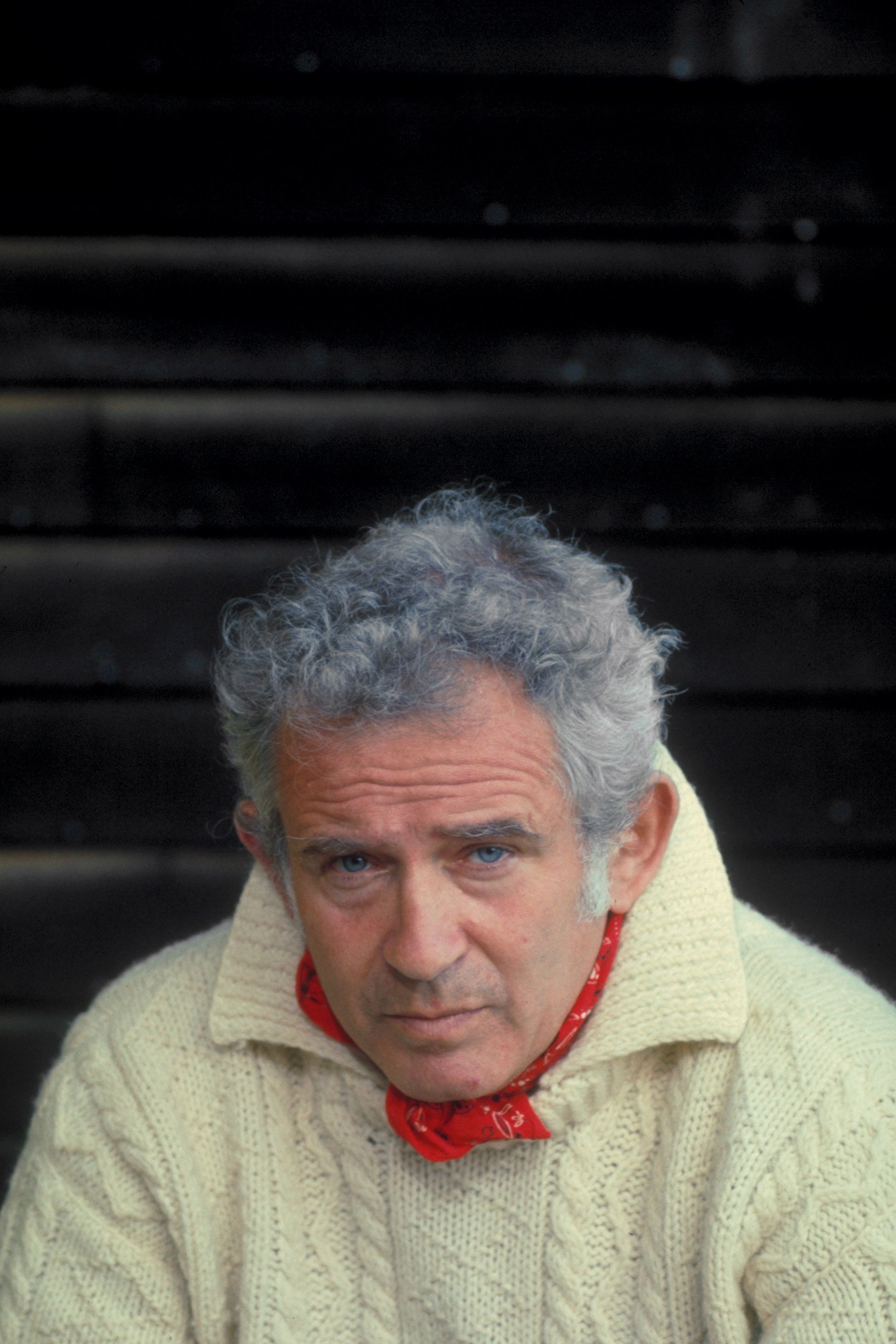

Let’s All Celebrate Norman Mailer

The most swaggering and macho of Jewish writers illuminated postwar America like no one else

Today would have been the 100th birthday of the greatest American voice of the ’60s, and the most truly American Jewish writer.

Norman Mailer was born on Jan. 31, 1923, in Long Branch, New Jersey. His mother gave him the Hebrew name Melech: king. She was prophetic. For decades, Norman Kingsley Mailer ruled the literary world. No writer was more famous in his day than the pugilistic Mailer—a colossus on the New York literary scene, author of bestselling novels, a frequent guest on TV talk shows and a high-profile reporter for glossy magazines. At his frequent best, he illuminated postwar America like no other writer.

These days Mailer’s macho bluster, sexist gibes, and ferocious ego offend contemporary sensibilities. May his name be blotted out! But Mailer amply deserved his stardom. He could be crude, silly, or even brutal, but more often he hit his targets. Mailer told hard truths about male violence, fought against conformity, and denounced the nightmare reign of technology. By embracing the twinned ideas of God and unreason that constitute the nuclear core of humanity, he drew upon a mighty source of energy that was simply not available to his more modern, right-thinking, constipated peers.

Mailer hung out with the Beats in the ’50s, took his place among the New York intellectuals in the ’60s, and cavorted with celebrities. He tried to punch McGeorge Bundy at Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball, ran for mayor of New York, and directed some crappy, jerry-built movies. (The best of them, Maidstone, is memorable mostly for the scene where Rip Torn attacks Mailer with a hammer.) For decades he lived among the bohemian riff-raff in Provincetown, and he wrote a peculiarly lurid mystery novel set there, Tough Guys Don’t Dance.

Mailer was one of the earliest and loudest opponents of the Vietnam War. He drew our attention to the barbaric conditions in America’s prisons. He condemned the public housing projects that turned Black neighborhoods into urban hellscapes. He warned against “the cold majesty of the Corporation,” which has now taken over our world, turning human problems into algorithms and personal identity into a consumer choice.

Mailer spearheaded the New Journalism, where the reporter’s ego strides into the limelight. No one but Mailer could have given us such diamond-hard portraits of American politicians, from Barry Goldwater and Eugene McCarthy to Mayor Daley. He knew their faces, their manners, and their inner tensions like no one else. He reported on political conventions, moon landings and heavyweight boxing, and wrote about Picasso, Marilyn Monroe, and graffiti artists. His portrait of JFK, “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” helped Kennedy win the 1960 election, or so Mailer thought.

In his rapturous mode, Mailer produced cascading depictions of the Chicago stockyards, the hippies at the Pentagon, and, late in his career, the orgies and mystical rites of the Egyptian pharoah’s court in Ancient Evenings, an epic queer fiction that melds together sex, magic, religion, and politics. His writing mirrored his life, and vice versa. By the end of his life Mailer had been married six times and had nine children. He was a family man who was also a very busy writer and a highly practiced adulterer. In his brazen way, he could be unusually self-reflective, putting his shortcomings on display in a way that is foreign to today’s self-righteous polemicists.

Mailer first made his name at the age of 25, in 1946, with his WWII novel The Naked and the Dead. Mailer had been in combat, briefly, in the Pacific. The novel is flawed, with a clumsy structure and too many characters. But Mailer has a sharp eye for the exhausting rituals of wartime, the endless hauling of heavy machines through the jungle, the swollen corpses of the Japanese enemy. Near the end of the book, Mailer becomes an expert satirist. He shows how the American military brass prize a cold mastery that damages the soul. A few years later Mailer would look for an antidote to the rigidity and repression he saw all around him in the conformist ’50s, which was forecast by the novel’s sadistic General Cummings.

The Library of America has just reissued The Naked and the Dead, an edition that includes a selection of letters Mailer wrote to his first wife during the war. Many of the letters are revelatory. On Aug. 8, 1945, he reacted to the news of the atomic bombs dropped on Japan. Mailer the trudging, wearied army soldier shared little, he said, with bomber pilots, devoted as they were to the machine:

Flyers are the same way as sailors. They fight too in an abstract way in an abstract fluid. Their lives are also comfortable, lonely and horny, and again death is the devastating, incomprehensible thunder clap. Those are lives with no other stench than the smell of gas and metal and lubricating oil. They do not know that latrines and bodies and swamps are something hard to differentiate.

And the personification they give their machines nauseates me. It is the substitute for the loneliness and horniness, but it is also so frightening. We have come to the age when we love machines and hate women. The next step is religious awe, and the atom bomb looks like the last deity, the final form line of entelechy.

Mailer loved to provoke. He was overconfident, vainglorious, and a boaster, but also troubled by his unruly impulses and ideas. He expressed the trouble in his fiction, where he gave the unruliness full rein.

Take Sergius O’Shaugnessy, the hero of Mailer’s early story “The Time of Her Time” (1959), who is determined to give his Jewish girlfriend an orgasm. He finally pushes her over the edge by saying into her ear, “You dirty little Jew.” But the story is really about the cracks in the masculine ego. The girl has the last word. At the end of the story, as she leaves Sergius, she says to him, “You do nothing but run away from the homosexual that is you.” Mailer’s Sergius praises her for this wounding thrust: “And like a real killer, she did not look back, and was out the door before I could rise to tell her that she was a hero fit for me.”

Mailer’s actual response when called a homosexual was considerably more agitated. On Nov. 19, 1960, Mailer threw a party. He had planned to announce his candidacy for mayor that night, but it didn’t work out that way. Instead he got so blind drunk that, someone said, he didn’t even know his own name. He kept going out into the street and picking fights with strangers. Back in the apartment, his second wife, Adele Morales, told Mailer he was a ”faggot.” And so he drew a penknife and stabbed her twice, close to the heart.

Adele always said that Mailer had stabbed her during a psychotic break. He spent 17 days in Bellevue. But he refused to plead insanity. The assault, he knew, was his “offense against God.” He worked out what that meant in his later books about violent men, notably The Executioner’s Song (1979), his largest masterpiece, which like the best of his writing was a work of nonfiction.

Those who visit Mailer’s attic study in his Provincetown home ascend a flight of rickety stairs to the small desk where he did his writing. Even in his final days, when he used two canes, Mailer climbed the stairs to sit down to work. (Michael Lennon, Mailer’s biographer and friend, movingly evokes this period in his recent book Mailer’s Last Days.) On the wall by the staircase hangs a sign: “Bellevue,” where Mailer spent three weeks after the stabbing. He never forgot the results of his reckless violence.

Mailer was not just exhibiting maleness in his work, as critics often charged. He was also showing the costs that masculinity exacts. At times, though, he celebrated aggression, as in his 1957 essay, “The White Negro,” which became a Beat scripture.

The style of “The White Negro” can be clotted and overheated—Mailer was apparently taking speed when he wrote it—but the essay is a true child of the Emersonian tradition. Like Emerson, Mailer denounces soul-killing conformity. The ‘50s were awash with “the wrong kind of defeats,” which, Mailer says, “attack the body and imprison one’s energy until one is jailed in the prison air of other people’s habits, other people’s defeats, boredom, quiet desperation, and muted icy self-destroying rage.”

Striking back at the Eisenhower era’s death-in-life was the hipster, who has a psychopath’s jittery energy and is able to use it creatively, “set[ting] out on that uncharted journey into the rebellious imperatives of the self.”

The heroic image of the Black street criminal in “The White Negro” was applauded by the likes of Eldridge Cleaver, whom Mailer helped free from prison. But here Mailer got things wrong. Black jazz musicians, not inner city thugs, supplied the models of African American style taken up by the Beats.

In “The White Negro” Mailer wrote,

Any Negro who wishes to live must live with danger from his first day, and no experience can ever be casual to him, no Negro can ever saunter down a street with any real certainty that violence will not visit him on his walk.

Here Mailer romanticizes and misleads. Not every Black person lived on the edge, even in the 1950s. Some of them lived in the suburbs.

Mailer explored the ecstatic unleashing that violence supplies in the lurid hardboiled novel An American Dream (1965), acclaimed by Joan Didion and Germaine Greer. Mailer depicts a wife murderer who gets away with it. Not only that, he buggers the German maid—a reflection of Mailer’s experience in Berlin, where he was able to celebrate his victory over a German prostitute who was so enthused about his sexual powers that she refused to take money from him.

An American Dream, full of swashbuckling Mailerian rhapsodies, reads like a Jim Thompson pulp fiction dressed up for a fancy dinner. One critic called it “a wild battering ram of a novel,” and so it is. When Stephen Rojack, the hero, murders his wife, Mailer’s book vibrates with perverse, terrible exhilaration. But in the end the novel’s action is too over the top, the dream too absurd. Both sublime and silly, An American Dream is a tour de force that defeats critical judgment.

Perhaps no other great novelist has produced such conspicuously bad books side by side with his great ones. The Deer Park is a misfired fable of Hollywood where every character seems bloated and unreal. Why Are We in Vietnam? is a near-unreadable hash. The narrator’s Texan slang sounds irritatingly fake, and though it poses as savage and satirical, the novel seems merely ridiculous. Mailer was always best when he drew directly from life. His purely fictional characters seldom convince the reader.

Mailer was a rebel by nature. After attending Mailer’s 1962 debate with William F. Buckley Jr., the 25-year-old Abbie Hoffman wrote that Buckley stood for “all the rah-rah baloney, the genteel and gentile power structure ... Buckley represented the empire, and Mailer was challenging the empire as a hip ethnic street fighter. That was extremely appealing to me.”

But Mailer had deep criticisms of the counterculture, and they were good ones. Reporting on the Yippie uproar in Chicago’s Lincoln Park during the 1968 Democratic convention, Mailer knew that such a barbaric yawp could never get very far, because it terrified the American burghers who needed order and security. Lured by the Yippies’ wild energy, Mailer also felt threatened by it.

Mailer saw into the deep fissures of ’60s America. Some of these divisions are still here today, like the one between a progressive, college-educated elite and an underclass that cares far more about bread-and-butter issues than about the involuted theorizing of elites. He saw how ferociously white working-class America hated the hippies who opposed the Vietnam War. There was a huge gulf in experience between the working class and the university-bred student protesters, who had never fired a gun, fixed a car, or gotten into a fight over a girl.

Mailer explained the late ’60s better than anyone, because he knew the actions of the radicals were foolish as well as profound.

Mailer explained the late ’60s better than anyone, because he knew the actions of the radicals were foolish as well as profound. He wrote two books on the clash between the antiwar youth and middle America: The Armies of the Night (1968), which won both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize, and Miami and the Siege of Chicago, his report on the 1968 political conventions.

Even as he griped about Women’s Liberation, Mailer admitted he had been schooled by the women. The Prisoner of Sex, which sparked a sensation when it appeared in the pages of Harpers in 1971, displays an unexpected regard for feminist insight. The male conceit that men were tough and women weak and sentimental, Mailer knew, was a total fraud. Women walking down the street, Mailer realized, were starkly exposed to the eyes of men, and, he confessed, “any man feeling so stripped of his skin would be suffering an unholy mix of narcissism and paranoia.”

Town Bloody Hall, that grand hoot of a documentary by D.A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus, shows the outnumbered Mailer squaring off against a passel of feminist firebrands. The lioness in the pack was Germaine Greer, who told the press that she had come to debate Mailer because she wanted to sleep with him (“I’d really like to help that man”). Mailer turned down the rock-star gorgeous Greer, perhaps out of fear.

Mailer argued that the feminist avant garde technologizes women, reducing the mysteries of sex to an engineering puzzle. Ti-Grace Atkinson wanted to free women from the womb—she hoped that babies could be made in test tubes. For Mailer this was technology trying to rule human nature. He rejected the outsourcing of sex, since for him eros was a confrontation between a pair of live human beings.

In The Executioner’s Song, Mailer honed in on the dance of sex and death through the stormy relationship between a killer and his girlfriend. Here he measured the damage done by the rebel stance he had earlier touted and fantasized about. Gary Gilmore’s rebelliousness is dismal and doomed, and leads to two senseless murders. But when sent back to prison he deepens. Gilmore’s letters to his girlfriend, Nicole Baker, which Mailer quotes at length, astonish us with—it must be said—their wisdom. Nicole, a tough, fascinating woman, is just as fully drawn as Gary.

Like Mailer, Gilmore believes in reincarnation, and says he is paying a debt from a past life. His demand to be executed makes him a figure of some nobility, and the night before he faces the firing squad is not unlike the Last Supper. Yet we never forget Gilmore’s evil, whose roots seem obscure both to him and to the reader.

Written in a spare style that continues for over 1,000 pages, The Executioner’s Song builds on itself, offering a panoramic view of hundreds of characters. Mailer dignifies even the most minor-key or benighted people, letting us hear each voice separately—the book is a symphony of free indirect style. In The Executioner’s Song, Mailer achieved a Tolstoy-like equanimity. His characters get their due, all of them. For once, Mailer himself doesn’t appear in the book.

Mailer called The Executioner’s Song, which won the Pulitzer, a “true-life novel.” Oswald’s Tale (1995) is a companion piece, also with a large cast of characters surrounding the killer. Mailer gives us Oswald through the eyes of his wife, Marina, whose story occupies much of the book, but we also get a strong taste of how Oswald saw himself. Disillusioned with both Russia and the U.S., Oswald wanted to promote his own eccentric third way, neither capitalism nor communism. So he decided to kill the president, thinking this cataclysmic act would shake the world and draw people to his homemade ideology. Oswald acted alone, says Mailer, though Jack Ruby did not—Mailer argues that Ruby obeyed Mafia directives when he killed Oswald.

When he murdered JFK, Oswald damaged America’s being, and he did it for an insanely self-aggrandizing purpose. The wound remains open to this day.

Oswald was the opposite of Gilmore, an ideologue rather than a spiritual seeker, and so completely unable to think of himself as guilty. Like Hitler or Lenin, Oswald believed he was the heroic catalyst for a new era, but he was just the victim of his own delusion. Mailer’s Gilmore, by contrast, was a thinker, though he never faced the true depth of his guilt. With Gilmore, a disturbingly real hero-villain, Mailer presented a riposte to all the outlaws and rebels celebrated by American culture, who are mere thrilling fictions next to the thing itself, the killer who decided to die for his crimes.

While writing The Executioner’s Song Mailer became tragically involved with a prisoner who had started writing to him, Jack Henry Abbott. Impressed by Abbott’s writing, Mailer helped free him from jail—or so he thought—and found him a publisher. (Mailer didn’t know that Abbott had actually been let out because he snitched on a fellow inmate.)

On one singular weekend in 1981, Abbott’s much-heralded book about prison life, In the Belly of the Beast, landed on the cover of The New York Times Book Review, while Abbott murdered a young waiter in the East Village. I was a few blocks away at the time, an undergraduate at NYU, where I had just read The Executioner’s Song for an English class. One of my closest friends knew Richard Adan, the waiter that Abbott killed. Mailer’s plea that Abbott be given a light sentence for his crime was a grave error, based on his mistaken sense that Abbott the writer had a higher claim than the public that needed to be protected from him. The Abbott affair continued to plague Mailer, who believed he shared the guilt for Abbott’s release and his murder.

Mailer has not usually been seen as a Jewish writer. He said many times that his stint in the army allowed him to escape his middle-class, nice boy, Jewish upbringing. But while writing for the Village Voice, the ultimate American Jewish publication which Mailer founded with Dan Wolf, Mailer became a fan of Buber’s Tales of the Hasidim, and later on he acquired a Soncino Talmud. Introducing his novel about Jesus, The Gospel According to the Son (1997), Mailer remarked that Jesus was “extremely Jewish. He worries all the time, he anticipates, he broods upon what’s going on, there’s an immense sense of responsibility.” Mailer’s profoundly anxious and aware Jesus is the antithesis of his Oswald, the psychopath who never doubted his grandiose, rash impulses.

According to Judaism, Mailer writes, you never get rescued by God “without paying something in return,” an idea that harmonizes with Mailer’s belief in karma and reincarnation. Remembering what you owe cuts against the belief in bold action and carefree daring so ingrained in American myth, and the trust in hipster originality that Mailer started with in “The White Negro.” Mailer now argued that you can’t make yourself up anew or cut yourself free of the past.

Mailer called himself a left conservative, and with this, too, he argued against the grain in a particularly Jewish way. During his quixotic campaign for mayor of New York City in 1969 (endorsed by Bella Abzug and Gloria Steinem!) Mailer advocated seceding from New York state, banning cars from Manhattan, and “compulsory free love in neighborhoods that vote for it.” He sketched his left conservative philosophy: “Speaking from the left, it says a city cannot survive unless the poor are recognized, until their problems are underlined as not directly of their own making.” And from the right, Mailer argued, “Man must have the opportunity to work out his own destiny, or he will never know the dimensions of himself, he will be alienated from any sense of whether he is acting for good or evil.” The social system has damaged people, Mailer knew, but every person, no matter how disadvantaged, must “work out his own destiny,” using personal courage alone.

Courage was a key value for Mailer. Courage meant the strength to take risks, including physical ones. Mailer saw how boxers incarnated courage. Men had died in the the ring, and Mailer was at ringside during the fatal knock out of Benny Paret, the most famous ring death in boxing. His admiration for Muhammad Ali was immense. Ali, then Cassius Clay, stepped into the ring with Sonny Liston, the most frightening man in boxing, and years later Ali in Zaire decided, maybe at the last minute, Mailer thought, to go for the rope-a-dope against George Foreman, the hardest puncher on the planet.

Where the great boxers staked their bodies, Mailer’s courage was intellectual and moral (as was Ali’s, too, he knew). Testing others and himself, and frequently picking fights, Mailer struggled honestly. He stuck to his ideas about America and the world, about men and women, in the face of counterarguments from the left and the right, without ever losing his will or abandoning the fight. He was of nobody’s party but his own—and ours. Let’s celebrate him.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.