Ofra, the Mayflower of the Settlements

The author of ‘The Hilltop’ revisits the lands and people Amos Oz confronted in the early 1980s to see how far the West Bank settlements have come, and where they are headed

The walls of the first houses of the West Bank settlement of Ofra are now affixed with the ubiquitous blue signs of Israel’s Heritage Conservation Council. “Here the founding fathers of Ofra established the first Jewish settlement in the mountain region,” one reads. “Here important decisions were made and, in order to make those crucial decisions, the public was summoned by the PA system on the roof,” says another. It’s a mythology that is similar to that of Israel’s first kibbutz, just over 40 years after its establishment. What does it mean for Ofra, and for the settlement enterprise as a whole? When a historical building becomes a museum, doesn’t it mean that that history is now settled?

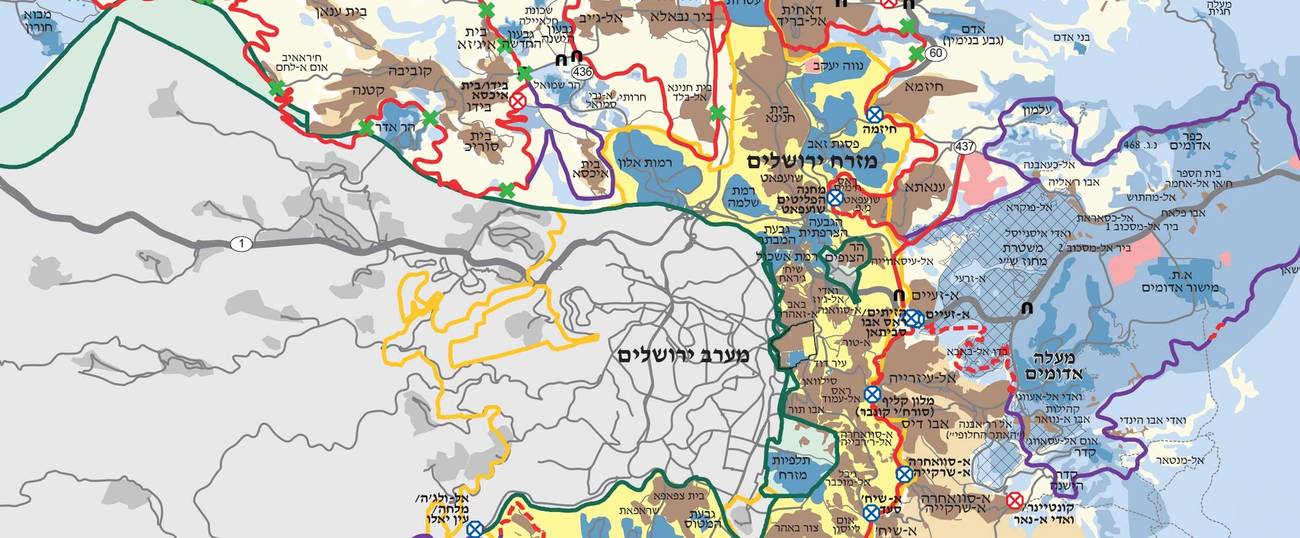

One of Ofra’s first buildings is now a pizzeria. Across the road is Ofra’s enormous religious high school for girls. Opposite it, a drab supermarket. None of these three buildings was there when the novelist Amos Oz visited Ofra in the fall of 1982, but the nearby field school was and it is still operating. The description of the school and its glass-eyed taxidermies starts a chapter of In the Land of Israel, Oz’s landmark book of meetings and analysis around Israel of the time.

Oz’s book of travels through Israel was not only a huge bestseller, but a dazzling admonition by a prophet at the gate. Between Ashdod and Bet-Shemesh, Ofra and Tekoa, Ramallah and Jerusalem, Oz documented a colorful yet disparate jumble of camps, ideologies and geographies, that, taken together, seemed to foretell an irreconcilable future. When the novelist researched and wrote his book in the fall of 1982, Israel was in the midst of what would turn out to be only the first Lebanon War—only a year after the evacuation of Sinai as part of the Camp David peace treaty with Egypt. In 1982, it likely took Oz over an hour to get from Jerusalem to Ofra. He drove north to Ramallah, crossed the city and then drove on the twisting Ramallah-Jericho road through the villages of Beitin and Ein Yabrud, until he reached the settlement. In 2019 it took me 12 minutes, using the new road network that was built as part of the Oslo accord, and bypasses the Arab towns and villages.

Other changes since then: two intifadas, one Oslo accord, the evacuation of the Gaza Strip settlements, mostly right-wing governments. Also, the Jewish Underground, three members of which were, and still are, Ofra residents. The number of settlers, in Ofra and elsewhere, has risen about 25-fold.

Last December seven people were injured in a drive-by shooting by Palestinian terrorists at the Ofra bus stop, and the unborn child of one of the injured women died. A soldier with a machine gun is now posted behind a concrete block next to the bus station. In the most recent Israeli elections, almost 70% of the 1,445 voters in Ofra supported the right-wing-relgious Yemina party, 17% voted for Netanyahu’s Likud, and 10% gave their voice to the extremist Jewish Power party.

***

“I never understood why the book became such a hit,” said Israel Harel, who hosted Oz at the time, and who was one of the central interviewees in that first chapter. “Quite an ordinary report,” he remarks, “there are many others just as good.” However, the evening that Oz made his speech to the settler audience was unforgettable. “There wasn’t a soul outside, everyone was in the dining hall. There was nothing like it before or after in our history, even when great rabbis came, or Hanan Porat, who was the most charismatic leader of the settlement movement, or government representative Yossi Beilin, who came at a critical moment, shortly before the Oslo Accords passed in the Knesset. Amos fascinated us all. Following his presentation, we argued with him all night. I must give him credit for leading this unforgettable experience.”

We met in a crowded café in Tel Aviv at night. Harel is 81 but after a two-hour conversation he had far more energy than I had. Oz described him as “a pleasant, thoughtful man, who speaks without exclamation marks and knows how to listen with a wise heart.” I’ll go with that. When he met Oz in Ofra, Harel was already the head of the Yesha Council, representing all the settlements in the occupied territories of Gaza and the West Bank, and the editor of the settlers’ monthly, Nekuda, both of which he founded and went on to lead for 15 years. He is still one of the quiet leaders of the settler movement and writes a weekly op-ed column in Haaretz, Israel’s prestige liberal newspaper.

He thinks Oz could have been on their side, if not for poet Nathan Alterman’s ego: “After the Six Day War, the Land of Israel movement was founded. I was in my twenties and was invited to join after publishing a couple of opinion pieces. We had the nation’s leading writers—Alterman, Moshe Shamir, Agnon, Hazaz. They drafted a petition and sent me to get signatures. I suggested inviting Oz and A.B. Yehoshua, but Alterman screamed at me, ‘No way!’ It was because these young writers had rebelled against his generation. I told Amos in Ofra, ‘If we had offered, you would have joined.’ He thought for a moment and said, ‘I don’t think so.’ But I do. There were left-wingers who signed and moved to our side, and if those two had signed on I think perhaps history would have looked different, because both became strong and fluent intellectual opponents. It was a mistake.”

Harel stopped speaking with Oz after the latter’s “dark cult” speech, in which he called the settlers, “a messianic, cruel cult, a mob of armed gangsters, criminals against humanity, sadists, pogromists and murderers, who emerged from a dark corner of Judaism.” Oz was probably referring to the extremist violent Jewish Underground and Rabbi Meir Kahane’s supporters, but Harel saw it as an attack on the more mainstream Gush Emunim settler movement. “I never forgave him. It was a violent outburst.”

***

“We played a little trick on them that allowed us to stay here,” Pinchas Wallerstein, the former head of the Binyamin regional council that covers the central part of the West Bank for almost 30 years, told Amos Oz at the time. If Harel is the ideologist, Wallerstein is the wheeler-dealer. “We took advantage of the bad blood between Rabin and Peres, and very senior and important people simply shut their eyes.”

When I visited Wallerstein in Ofra in 2019, his cellphone vibrated with messages concerning his attempt to get hold of permits for an outpost erected by youngsters in the Arava desert. He spoke to Yoel Rivlin, the president’s son, who works in the Settlement Division, with the Nature and Parks Authority, and with the defense minister’s settlement adviser. He called himself, “An Adviser for Complicated Matters.” Earlier this year a biography titled The Wallerstein Route was published, detailing his extensive activities.

‘You think that letting go of the West Bank will pose an existential danger to the state of Israel. I think that annexing these lands will pose an existential danger to the state of Israel.’

“Why did Amos Oz publish this book?” he asked. “He set out to find all the tribes in Israeli society. Theoretically it was a fine idea, to find the unified Israel. But what he discovers is that each and every one is in his own corner, in his hothouse. Oz came to us as a former kibbutz member, for us it was an honor. After all, our mentors and supporters in Ofra’s early days were the kibbutzniks. We were a semi-kibbutz ourselves, with strict unifying rules down to the color of the rooftile, with a communal dining hall and regular meetings of the assembly. Oz represented the romanticism of the sabra, the Israeli-born. We liked him coming despite the dispute. The dispute was only about location. We did not have an ideological dispute with him: a democratic-Jewish state, Zionism. Even centrist leaders Benny Gantz and Ehud Barak do not dispute that. Only one thing changed for me since then: I remember telling Oz that I would stay in Ofra under any circumstances. Not anymore. I am a part of the Israeli society under any circumstances. This is my guiding principle. I will even give up my house for the benefit of the state. My motivation today is to reduce the height of the flames in Israeli society.”

Despite this conciliatory and dignified approach, I must dispute the idea that there is no dispute. The starting point may be similar: settlement, pioneering, villages in the line of fire. However, Oz was quick to recognize this already in 1967, and in 1982 he already made a clear distinction. His speech in the second Ofra chapter of his book phrases in a piercing and still painfully relevant way, the gap between the settler camp and the humanist camp in Israeli society: “You think that letting go of the West Bank will pose an existential danger to the state of Israel. I think that annexing these lands will pose an existential danger to the state of Israel.”

This is the bottom line, and it hasn’t changed. But beyond the “dispute about location,” Oz speaks of the indifference of the settlers to his side’s moral distress, and diagnoses that from their point of view there is no legitimate argument between two opposing perceptions, but a patronizing and arrogant view that claims there are authentic, real, knowing Jews, and across the road rootless, pervert unbelievers. “No one has a monopoly on Judaism,” writes Oz, and defends the pluralists’ right to decide, to import, to oppose—and develop a live, updated culture, universal rather than tribal. “Museum-like civilization” he defined their approach, blaming them for having “moral autism” and being hypocritical toward the world outside Israel. It would be fair to ask if his words are still relevant in light of the far-reaching changes that took place since 1982 in the world, the region, the state. I believe the answer is yes, and even more so now, 37 years later, the gap is the same. Mainly because, however one tries to approach it, we are still occupying another people.

***

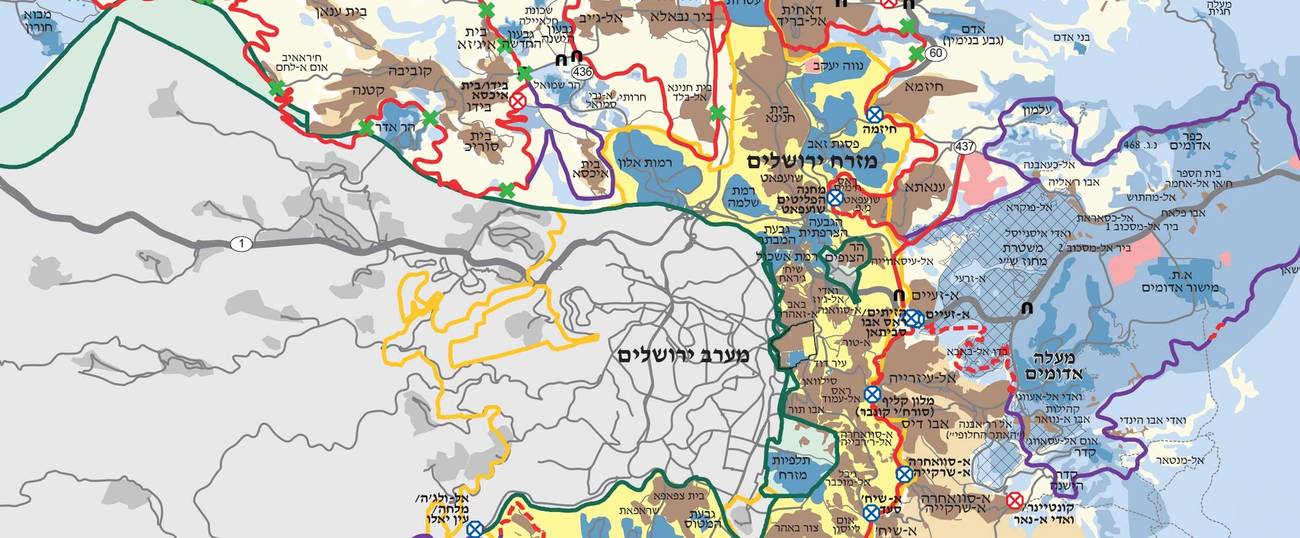

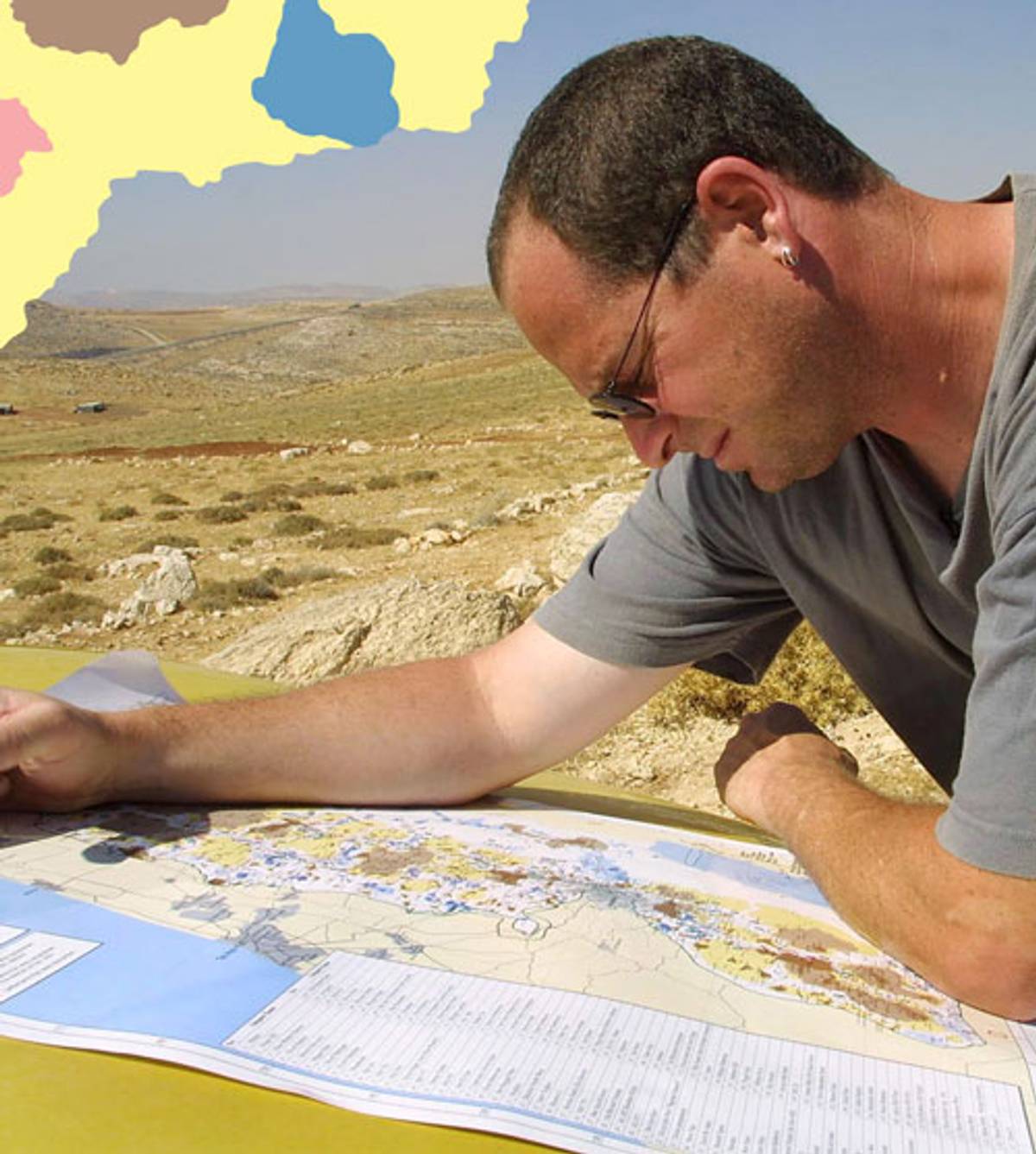

Dror Etkes was a religious teenager in the Ramat Eshkol neighborhood in Jerusalem in 1982. Twenty years later he started documenting the settlements and outposts in the West Bank, first for the Peace Now organization, then for Yesh Din, a legal NGO, and today with Kerem Navot, a nonprofit he founded in 2016. He drove me around in his tiny Chinese-made car. “In 1982 Ofra was situated in Jordanian buildings that were constructed between 1966 and 1967, in an army base that the Kingdom of Jordan expropriated from the Palestinians. The buildings were never completed. Most of the expropriated land, about 60 acres, was never used by the Jordanians. When Ofra was established in 1975, the residents used the military infrastructure that the Jordanians left behind. But in the early 1980s Ofra started expanding into the land of the neighboring villages of Ein Yabrud to the west and Silwad to the north, beyond the expropriated land.

“Apart from the Jordanian area and four more plots acquired over the years by the settlers, the whole settlement is built on land that is privately registered to the people of Silwad and Ein Yabrud. About a third of Ofra is built in the formerly Jordanian area, around 200 houses, and two-thirds, close to 500 houses, is built on private land. Beyond that, Ofra controls 1,160 acres of agricultural or abandoned land, which Arabs are not allowed to enter, despite being its legal owners.

“Note that most of the West Bank is not registered. Jordan only started the registration process and when Israel occupied the land, registration stopped. But the land east and northeast of Ramallah was registered, and its owners are known. So, when you talk about stealing land, Ofra is unmatched. There’s no shortage of problematic places in the occupied territories—Bet-El, Elon Moreh, and others, but in Ofra they really went wild. The place stinks, extremely so.”

Etkes is personally responsible for three major failures in Ofra’s history, the evacuations known as Amona 1, Amona 2, and “the nine houses.” In February 2006 nine houses were evacuated and destroyed in the Amona outpost that sat on the hilltop to the east of Ofra, following an appeal submitted by Etkes, claiming that the houses were built on private land. Israel’s Supreme Court accepted his appeal. In January 2017 the remainder of the Amona outpost was evacuated, 40 houses by this time. (The families were compensated with land and houses in a new settlement called Amichai, specially built for them.) One month later nine houses were evacuated and destroyed in the heart of Ofra’s southern neighborhood. This time it was the Palestinian land owners themselves who appealed, with Etkes following the process closely.

Etkes is very skilled. He changes cars frequently, hides his ginger head and green eyes behind hats and sunglasses. His sensors are working all the time—on the day of our visit he identified a new sheep farm and a few temporary huts that he assumed were built by youngsters during the summer. He drove me to what used to be Amona and is now a closed military zone (nothing stopped us from driving in; only two deer blinked at us curiously), and showed me the foundations of the destroyed houses, with remains of electricity boards and sewage pipes. “They failed,” he said, “because the evidence was strong.”

Was it important for you to act here especially? “In different places in the West Bank they use different tricks, and it’s important to act in all of them, but the case of Ofra is ironic because important people live here. I call Ofra ‘the Mayflower of the settlements.’ It is a successful, rich, established settlement. Its residents have high self-esteem, and rightly so. It produced the most significant leaders in the settler movement. But it is in serious trouble.”

Don’t the three evacuations encourage you? Show that it is possible to enforce the law? “I don’t see it as a success, because the Palestinian land owners still can’t access their lands. Besides, it is only pretense law enforcement. All the houses in the southern neighborhood that surround the nine evacuated houses have the exact same status as them, i.e. are on private Palestinian land. But the state doesn’t move a finger to evacuate them, only because there is no high-court order. It demonstrates how ridiculous the law is here.”

So why do you do this? “I want to force the state to decide on which side of the law it stands.”

***

One of the houses still standing on the demolished street is the Sorek family house. At the beginning of August a terrible tragedy hit the family. Their 19-year-old son Dvir was murdered by a Palestinian in the Gush Etzion region, close to the Mahanayim yeshiva where he was studying. Dvir’s father, Yoav, is a known figure in the national-religious camp, a journalist and thinker who publishes his writing in the periodical Hashiloach, which he also edits.

At the age of 49, Yoav Sorek can be seen as a dominant representative of the next generation after the founders of Ofra, but he has no pretensions to holding such a title. We sat in his garden recently, under an olive tree and next to a small swimming pool. He was a pleasant, soft-spoken man. “I didn’t come here for ideological reasons,” he said. “Twenty-two years ago, my wife and I moved to the Rechelim outpost, a few miles up the road, when there were only three trailers there. It was a little extreme for us, so we came to bourgeois Ofra. It is fun to raise children here, though it could have been similar in a community village within the recognized borders of Israel.”

Born in Rehovot and raised in a right-wing house, he has lived “on the right side of the green line” since he was 15. I think that Amos Oz would have admired his thinking, which calls religious Judaism to recalculate its route. In a long essay, published in the October issue of Hashiloach, he relates to the same division that Oz criticized in that speech in front of the Ofra people, between the fossilized, “museum-like” Judaism and the pluralist, universal, open version.

Sorek does indeed call for a link between the messianic and the realist, the mythical and the universal, but the deeper you delve into his essay, it seems that the complaint is predominantly against the side that disapproves of the mythical and messianic. And when he moves from theory to reality, you read statements like, “The messianic realism of Gush Emunim was not understood,” or “Netanyahu knows that Israel is not ‘just another state.’” However, in conversation, he will honestly admit to the failures of the settlement enterprise: “For most Israelis we are still beyond the dark mountains; we have no sovereignty, no master plan, no government that will naturalize the West Bank.” He will even express ideas that are heard almost only on the left and Palestinian side, like focusing on 1948 and not 1967, and suggesting the rehabilitation of the Palestinian refugees. But he believes in the “Great Jewish Story,” and thinks that secular Zionism is detached from it, thereby seeing the settlements as “a colonialism that sucks—you are left with Amos Oz’s metaphor about us clinging to the board in order not to drown. This is wretched in my eyes, mere survivalism.”

Sorek supports the deportation of terrorist families: “Destroying their houses does little damage. Deportation sends a message that there is no tolerance for those who don’t respect us. The only ones who are left are those who accept our existence. It will decrease the radical element and encourage coexistence.”

But the families did not murder, individual members did. “The murderers did not operate in a void. The mosque, the education system, this is what they grow up hearing. There is an element there that is stronger than the human. We need to concentrate on changing the vector. Once they realize we are here to stay, they will go with us. We should encourage their emigration on the one hand, and their will to join us on the other, including conversion. The key in neutralizing the hostility is to be strong until they come to terms with us.”

I believed Sorek when he told me that he doesn’t hate Arabs and that he educates his children to what he calls “well-meaning nationalism.” But I can’t accept the assumption that the national feeling on the other side is essentially odious. Nor do I accept the patronizing view that we can educate the Palestinians and define who they are and what is good for them.

When I asked him about the nine houses down the road he jumped up and led me upstairs to view the neighborhood. “It’s simple,” he said, “there is the law, and there is morality. The land is private administratively, but not morally. There wasn’t ever a person who thought this land was his. Look over there to the park between the neighborhoods. That land belongs to a friendly Arab and no one touches it. In Amona there were never any Arabs. The place was deserted. They destroyed it for the sake of destruction. Amona was built in harmony, a kind of a Woodstock, wooden houses, integrated with nature. The settlement they built for them instead, Amichai, cut into the mountain aggressively and ruined nature over there. What’s the point? And the nine houses here on our street, it was just a provocation, an action to annoy us. No one will get those plots anyway. It was a waste of millions. Just so that the evacuation vehicles could pass, they paved dirt roads, ruined vines, and no one asked who owned that land. They’ve spilled tons of limestone that ruined nature.

“I sleep well at night because I did not take land from anyone. The fact that the land has no status is due to the weakness of the authorities. I hate being presented as doing something which is against my values. It is not who I am.”

***

Esther Brot is the captain of Ofra’s women’s netball team. Age 34, she was born a few years after Oz’s visit and book. She hasn’t read it. Unlike the experienced veteran founders, who have been repeating their mantras expertly for decades, there was something fresh and authentic about her, even captivating, when we met. Energies of a millennial. Her eyes were big and smiling, her head covering partial and fashionable. She grew up in Ateret, a small obscure settlement, a seven-minute drive from Ofra. Brot and her family were living in one of the nine houses that were evacuated two years ago.

She is an interior designer and we sat in the pretty space she designed in the big house where the family moved after the evacuation, in a street of new houses within the regulated Jordanian expropriation area, opposite those first houses with the blue nostalgic signs. Her three children are around us, eating, playing, watching a movie.

She was a student at the Ofra high school for girls, which is how she got to know the place. She and her husband, Netzach, a lawyer working in Tel Aviv, were looking for a house, “a good place in the middle.” She knew Ofra was a leading settlement, “Great people, thinkers. We bought a house because we knew that if it didn’t work out, we could sell it easily. We didn’t come here to ‘drain the marshes’ [a reference to the early Zionist pioneers]. Obviously, you can’t be a lefty if you live here, but the reasons for the move were definitely comfort, standard of living, the society, and cheap housing.

“All these leaders—what could go wrong? Still, we tried to understand, because it was after the Gaza strip and Amona evacuations, and I remember asking the secretary, ‘What’s the story with the land here?’ I am not adventurous and not delusional. I realize where we live and know that there is always the danger of a peace agreement. But I asked if there is danger beyond that. He assured me there wasn’t.”

She opened a booklet with maps and photos, especially made to tell the story of the nine houses that were evacuated. “There was no one in our neighborhood,” she showed. “My complaint is against the government that didn’t regulate the land. It paved roads but hesitated when it came to ownership. And the leftist groups found their opening.”

A few days after the court appeal was made, they quickly moved into the house, although it was not finished. “The toilet arrived after us, and the rabbi gave us permission to work on a holy day. We had to “get in under the stretcher,” because half a million Israeli shekels were invested in these walls.”

This is “generation 2.5” of the settlers, as Brot called herself. You get under the stretcher not for the land of Israel, but for the half-a-million shekels. She talks about her rights as an individual and as a buyer, not a Jew.

They waited seven years in uncertainty while the appeal made it through the courts, “but everyone thought it would be all right. This is not Amona or the Gaza Strip. There were outrageous government decisions in those places, we thought, but not here. In the end it was worse. Even if the left loses the elections, it wins the bureaucratic system. The left controls the courts and prosecution.”

She said that the height of the humiliation was the realization that her fellow citizens didn’t care. “I was interviewed on a popular show and the host said, ‘you’re cool, why don’t you come back home?’ It was the first time I realized that society does not see me as part of it. I always thought we were protecting Tel Aviv. I didn’t ask for gratitude, but I thought I was part of the nation. That was the crisis for me. The state betrayed me, the court betrayed me, and now society has betrayed me. I feel that the left-wing organizations are not doing it because of their love for human rights, but because they want to trample on my rights.”

Or maybe they are striving to live in a law-abiding state and oppose controlling another people. “I grew up here. This is what I know. I am raising the fourth generation. We are still at war. We can’t leave. Having a border 15 kilometers from the sea is illogical. There is no solution, even Trump hasn’t got one, I’m sorry to disappoint you, but it is a religious war.”

Despite the uncompromising right-wing views that Brot and her fellow interviewees hold, there was something more open in her. She felt that the founding generation believed in an absolute truth, and it doesn’t exist anymore. She met the Darkenu (Our Way) organization, “and I realized there is an ideological left.”

Of the patronizing approach that Oz described she said, “We’ve learned since then, we are less arrogant. Or at least we know that we have to learn.” She has met Palestinians from the area as part of the “Good Neighbors” initiative and says she would be curious to visit Ramallah and Rawabi. When she sees Palestinians at army check posts she understands their feeling of humiliation. What changed her was the evacuation. “It shook my belief. I was religious out of inertia, and that started a process of understanding that the world was more complex. In a good way.”

The process was supposed to reach its peak when Brot was invited by Our Way to give a speech at the annual ceremony commemorating Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, two years ago. “I wanted to talk about unity, but not to apologize. I have criticisms about our project, I remember the contempt whenever Rabin appeared on TV, and that people rejoiced at his assassination. I think we must commemorate him in our schools. You never kill, it’s a simple message that should reverberate loudly. But the good old left-wing Meretz types felt I was stealing their ceremony, how dare I?”

After pressure from the left, her speech was canceled. “Zehava Galon put up a banner on her Facebook page, ‘Unity? No thanks!’ And Mossi Raz called me ‘the Inciter from Ofra.’ Are you serious? This is where Meretz lost me.”

***

I ended the long day in Ofra on an orange plastic chair on the Tel Aviv beach. Beside me sat Yehuda Etzion. Literally a gentleman, with a long white beard, white hair, and a big skullcap. He was part of the first group that started Ofra, and he was there on the night when Amos Oz spoke, apparently shouting and interrupting. He claimed he published a reply in Nekuda, but the next day I couldn’t find it in the library; perhaps the issue went amiss. Etzion was one of the leaders of the Jewish Underground, among those who planned to blow up the mosques on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, and consequently sat in jail for four and a half years. In the first Amona evacuation he was crushed by a police horse and won 35,000 shekels compensation from the state.

What happened since 1982? “Strengthening. Of us, and even more so, of the Palestinian enemy: their villages, the Palestinian Authority, their international recognition. The paradox is that as the power grows on both sides, the balance remains, meaning the fight has not been settled. In 1982 we felt we had succeeded, but who knows what will happen? A political change and we won’t survive. Now we’re stronger but there could still be an agreement that will cause distress.”

What will you do then? “I considered starting a movement called ‘Remain.’ We will stay anyway, you want to go? Go. There was a movement like that, when the population of Tel Aviv was evacuated during the First World War, when painter Nahum Guttman and others announced that they were not leaving. In Nahariya, too, which was out of the partition plan, the council drafted a paper outlining how to operate outside the state. Leaving was not on the cards.

Wallerstein said that to Oz in 1982, but today he told me he changed. “Pinchas wants a total overlap between the state of Israel and the settlers. I don’t. We are friends but are in ideological disagreement.”

Why stay? “It is the land of Israel. Like Hanita that was founded under the foreign governance of Britain. We settle, we are surrounded by Arabs, and yet we remain. The commitment is still there. If the State of Israel fails to govern, strengthen, deepen the roots, it does not oblige us to fail too—they can go.”

Who did you vote for? “I think the last time I voted was in 1977. I have an internal disagreement with the whole system and regime. A regime fits a culture. A vague culture gets a certain political system. At the moment both sides are unfit—the pot and the lid. We need a commitment to the God of Israel and the Torah, and this requires a regime of an Israeli Kingdom. I realize that now it is seen as a far-reaching and inappropriate vision. I feel more a citizen of the nonexistent Israel Kingdom of David than a citizen of Israel, and therefore I don’t participate. It’s OK, I live with the chuckles, even in my own house.”

Etzion sees amazing qualities in the young generation, though he admits his generation was more ideological then the one that followed. “Individual motives have prevailed—the small flower and not the wide field. I pray that the next generation will bring back the group and in a stronger way. I foresee a cultural revolution that will change the nature of Judaism and redeem the world. I call it the Jerusalem Annunciation.” Etzion has been working on planning the Temple, “with an architect and a team,” for the last six or seven years. They are planning the whole city, with the Temple at the center. “We’re dedicating many hours for this. It’s on the computer, waiting. It is something that must happen and will happen. I am careful with time predictions but ‘The Book of Reconstructed Jerusalem’ will be a consciousness catalyst. Like Herzl’s Altneuland was a consciousness catalyst for Zionism before there was anything. It opened minds.”

And what about Ofra? “A fine settlement. We started well and it stayed a nice, good place. The numbers have grown, thank God. But it’s not from ant to elephant, it’s from baby elephant to elephant. One can ask if its DNA has been kept. I think it has, partially.”

***

After many hours with the ideologist, the wheeler-dealer, the philosopher, the angry millennial, and the Temple dreamer, I summarize and generalize: All of them are passionate, undoubting right-wingers, admire the late Hanan Porat, and are devoted to the land of Israel. The Palestinians are invisible to them, but they offer solutions for their problem that somehow always include Jordan.

They have concerns, but also belief and confidence. Yehuda Etzion said, “The balance remains. They brought us down twice in Amona and with the nine houses. But the strengthening of our power means that we can be injured but not easily killed, the Ofra entity is stronger than that. We are durable. Pain, tears, well, OK.”

Israel Harel agreed. “Perhaps we were not flags for the whole nation but we were for a big part of it. We did our best.” He was not worried about the future of Ofra. “The Arabs will not accept Trump’s plan, because they don’t accept any plan. That’s our luck.” And Wallerstein added, “Ofra still leads the worldview of getting the most of what we can. And the consensus is changing in our favor.”

During our conversations I kept thinking about a sentence in David Grossman’s epilogue to the 2009 edition of Oz’s In the Land of Israel: “Again and again I thought to myself, it won’t work. There is no chance that we will ever live a normal life here.”

I don’t believe there is symmetry. I believe that the occupation is less morally acceptable than sporadic Palestinian violence. But I accept the debate. Its existence. Every side deserves to voice its opinion. And the feeling is that still—more than ever—most of the settlers don’t accept the debate. Oz wrote that already in 1982. And it is more extreme, institutionalized, and tolerated today. If anything, Oz was naive in even trying to preach to them that night, in believing that they could be convinced. Knowing the settlers since being a soldier in Gaza in the late 1980s, and later in my researching and writing, I don’t think such a scenario is feasible.

Recently Ofra saw, for the first time in its history, the arrival of a crane. The settlement is about to start building six-story buildings. It looks like it’s here to stay.

Assaf Gavron has published six novels: Ice, Moving, Almost Dead, Hydromania, The Hilltop, and Eighteen Lashes; a collection of short stories, Sex in the Cemetery; and a non-fiction collection of Jerusalem falafel-joint reviews, Eating Standing Up.