Holiday Books

High Holiday prayerbooks of every stripe

Even covering eight–10 titles each week, On the Bookshelf doesn’t always mention every book of Jewish interest that has been published. In the hopes of atoning to wronged authors and readers, On the Bookshelf’s Yom Kippur column will highlight a selection of such neglected titles. If you’ve noticed a deserving book that has been published since January 2010 but has gone unmentioned in Tablet Magazine, nebekh—use the search box, above, to double-check—please email [email protected] with the title. Thanks!

Among its other distinctions, the new Rosh Hashanah-Yom Kippur prayerbook produced by the Conservative movement, which will be used for the first time during the upcoming holidays, is almost certainly the first such book to be introduced with a book trailer and therein touted as a “game-changer.” Edited by a committee led by Rabbi Edward Feld and titled Mahzor Lev Shalem (Rabbinical Assembly, 2010), the book draws inspiration from its 1972 predecessor, including alongside the traditional prayer service many tidbits of poetry and spiritual reflections from modern and contemporary writers and rabbis such as Abraham Joshua Heschel, Leo Baeck, Martin Buber, and Lawrence Kushner. Among other noticeable features are the “bowing sign” indicating when to lean forward, and an English translation that attempts to avoid “arcane or baroque language” and to be “as gender-neutral as possible, while remaining faithful to the intent and meaning of the original”: as such, it translates “אָבִינוּ” as “our parent,” not “our father,” and “אָבִינוּ מַלְכֵּנוּ” as, er, “Avinu Malkeinu.”

The Rabbinical Assembly intends Mahzor Lev Shalem to appeal broadly: As Feld notes in the trailer, “What this book represents is Conservative Judaism as a big tent, and welcoming everybody into the tent.” Whether or not anyone accepts that invitation, the mahzor shows how attentive Conservative leaders have been to the success of Artscroll. As Jeremy Stolow notes in his recent study Orthodox By Design, Artscroll’s editors espouse rigid Orthodoxy—don’t expect any pussyfooting about God’s maleness from them—but market prayerbooks especially to those with minimal knowledge of Jewish texts and practice. Thus, the Seif Edition (Artscroll/Mesorah, 2000), a fully transliterated mahzor, sells itself with the tagline, “Can’t read Hebrew yet? It’s for you!” And the Schottenstein Edition (Artscroll/Mesorah, 2004) centers on an interlinear translation, preventing those who want to read both the Hebrew and English from looking like spectators at a tennis match. (And, yes, both are available bound in alligator skin, perfect for a newly frum wild game fetishist.)

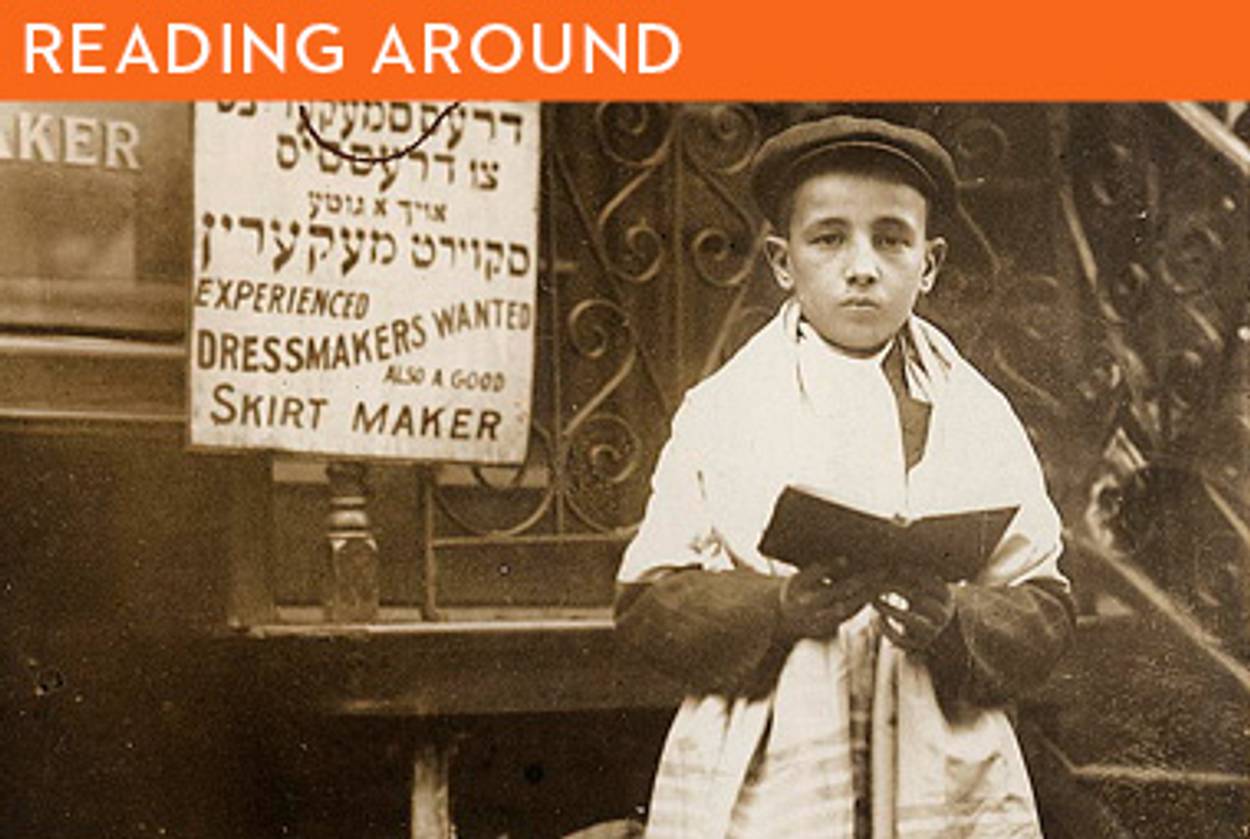

Mahzor Lev Shalem has other precedents: In Hebrew, poet Yonadav Kaplan’s Mimekha Elekha (Miskal, 2004) includes an even wider range of modern texts alongside the traditional Rosh Hashanah liturgy, with poems by Bialik, Leah Goldberg, and others, as well as quotations from political and literary figures like Ben Gurion or Haim Sabato. Offering a “gender-neutral translation” that goes even further than the Conservatives have, Ronald Aigen’s Mahzor Hadesh Yameinu (2001), meanwhile presents a Reconstructionist take on the liturgy, “reflecting a religious humanist theology.” Even at the reasonable price of $30, Mahzor Lev Shalem cannot quite undersell Mahzor Kol Bo (Star Hebrew Book Co., 1932), which is free for download from the National Yiddish Book Center and can easily be imported as a PDF file onto an iPad for convenient e-davening—though Kol Bo’s instructions and commentaries, in Yiddish only, may not appeal quite as widely in 5771 as the book’s lack of a price tag and digital format.

***

One constituency generally not catered to very well by standard holiday prayerbooks: little kids. To address this gap, a few children’s mahzors have been published in the last decade. The Yom Kippur Children’s Machzor (Gefen, 2006) includes photographs of clay sculptures “that reflect passages from the prayer” made on the occasion of her bat mitzvah by a 14-year-old Israeli girl. And the Reform movement offers Gates of Repentance for Young People (CCAR, 2002), which includes trippy, full-color illustrations and encourages older children to get into the spirit of impending judgment that suffuses the days of awe by recalling “a time you showed a report card to your parents.”

Much more common, though, are children’s picture books that eschew liturgy in favor of imparting basic facts and the spirit of the rituals, like Susan Schnur and Anna Schnur-Fishman’s new Tashlich at Turtle Rock (Kar-Ben, August, ages 5–9), with illustrations by Alex Steele-Morgan. The story features a girl named Annie, her family, and, predictably enough, some breadcrumbs and a creek. Don’t expect pap from this particular mother-daughter team, though: When Schnur, a rabbi who serves as editor at large for Lilith, talked to another one of her daughters and a couple of the young woman’s college friends about their dating life recently, it resulted in what the Jewish Week’s Gary Rosenblatt called “one of the most enlightening and disturbing articles on Jewish life that I’ve read in awhile.”

***

Nancy Rips aims for heartwarming rather than disturbing in High Holiday Stories (Frederick Fell, September), which puts the Jewish shmaltz back into the formula perfected by Chicken Soup for the Soul. Based in Omaha, Rips bills herself as “Nebraska’s book maven” and has assembled 101 anecdotes of holiday observance and cheer that shuttle from India to Iraq and Los Angeles to Houston and vary in subject from repentance to humor.

***

It’s not news that the tale of the akedah, or sacrifice, is at the center of the Rosh Hashanah ritual: After all, every shofar blast is a reminder of that hapless ram, caught in the wrong thicket at the wrong time, who took Isaac’s place on the altar. More surprising is the central place of that narrative in modern Hebrew culture, as traced by Yael Feldman in Glory and Agony: Isaac’s Sacrifice and National Narrative (Stanford, September). Feldman treats more than just Isaac’s story—she also considers the martyrdom narratives of Ishmael, Jephthah’s daughter, Iphigenia, and Jesus—and ranges from the dawn of the 20th century to the present, exploring the rich interplay between religious mythology and modern art, philosophy, and politics.

Josh Lambert (@joshnlambert), a Tablet Magazine contributing editor and comedy columnist, is the academic director of the Yiddish Book Center, Visiting Assistant Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and author most recently of Unclean Lips: Obscenity, Jews, and American Culture.

Josh Lambert (@joshnlambert), a Tablet Magazine contributing editor and comedy columnist, is the academic director of the Yiddish Book Center, Visiting Assistant Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and author most recently ofUnclean Lips: Obscenity, Jews, and American Culture.