Philip K. Dick’s Last Great Obsession

The Dead Sea Scrolls blew the sci-fi writer’s mind

That our perceived daily reality is an illusion is the idea most commonly associated with Philip K. Dick. It is the central theme of his many novels and stories. This constant questioning of our own perception of the world has even generated an adjective “Phildickian.” In that view the reality we perceive is a manipulated, artificial one, manufactured by sinister forces.

PKD, as he was known to his fans, has become a cult figure since his death in 1982 at age 53. In the last decade of his life Dick was immensely popular among science fiction readers and conspiracy theorists, and in the early 1980s his work captured the attention of Hollywood and his ideas influenced millions. Films based on PKD’s books included Blade Runner, Total Recall, A Scanner Darkly, Minority Report, and, most recently, the television series The Man in the High Castle, which imagines a post-World War II United States ruled by uneasy agreement between Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. In 2000, Emmanuel Carrere, Dick’s French biographer, wrote, “We are now living in Philip K. Dick’s world, a virtual reality that was a fiction in the past.” At a time when conspiracy theories about sinister Russian bots deciding elections and COVID-19 being manufactured in Chinese labs or as a part of a vast U.S. government conspiracy have become normalized on both the left and the right, it seems only right to pay tribute to the master.

Author of some 40 novels, and over a hundred short stories, Dick was a tireless and an indefatigable writer. Acknowledged during the last decade of his life as a great genre writer, he is now considered simply a great American writer. The Library of America has published three volumes of PKD’s novels. One of those volumes, Four Novels of the 1960s, which included both The Man in the High Castle and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, was the fastest selling title in the Library of America’s history.

Fueled by large doses of amphetamines, PKD could turn out a novel of a few hundred pages in two to three weeks. From the time he dropped out of UC Berkeley in 1947, PKD was determined to support himself through writing, and avoid all other gainful employment. For a decade he managed to make a modest living from his sci-fi novels. Amphetamine use, and the use of barbiturates and opiates to enable him to sleep, took a terrible toll on his physical and emotional well-being.

After what his psychiatrist described as a nervous breakdown, and Dick described as a set of mystical experiences, PKD joined the Episcopal Church and declared himself a “serious Christian.” He sought answers to existential questions in the scriptures of the great religious traditions. In his study of Jewish and Christian traditions he was inexorably drawn to the visionary, mystical, and apocalyptic. In the Hebrew Bible he focused on Isaiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel, and in the New Testament on the Gospel of John and the Book of Revelations.

Of the post-biblical writings, the Dead Sea Scrolls fascinated the novelist the most. It was his study of those texts, discovered in what is justifiably called ‘the greatest archaeological find of the 20th century” that led him to write his last novel, The Transmigration of Timothy Archer. The novel imagines that after the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls another cache of scrolls is found in the Judean desert: The “Gnostic Scrolls of the Essenes.” The narrator is drawn into the search for the secrets of these scrolls though his friendship with Timothy Archer, the bishop of San Francisco.

In a letter to his acolyte Claudia Bush, Dick shared his excitement about the actual Dead Sea Scrolls—and what he imagined they contained:

The contents of the Qumran scrolls would contain all the elements I’ve been entertaining in my mind ... The Essenes sent teachers to the various cities ... these teachers concealed their Essene background and training. Jesus Christ is the best known example (The Qumran scrolls indicate he was indeed “a secret Essene”). ... Nobody knew the sources of these teachings until the Qumran scrolls were recently found; No wonder Jim Pike and other theologians went crazy with excitement—saw Christianity in an entirely new light. ... Its in my head because I was Jim’s friend and so forth, as I’ve said. From the Qumran scrolls he got all this synthesis of the wisdom of Antiquity and then he died and then he “came across” to me and now I’ve got it.

Interest in the Dead Sea Scrolls led PKD and other spiritual seekers of the 1960s to identify the scrolls with the so-called Essene Gospels. These writings, published as The Essene Gospel of Peace, were a counterculture bestseller, available in many “head shops” and “metaphysical bookstores.” That these “Gospels,” which presented Jesus as an Essene, were an early 20th-century forgery was of little interest to those seeking “alternative scriptures” with which to subvert the claims of organized religion.

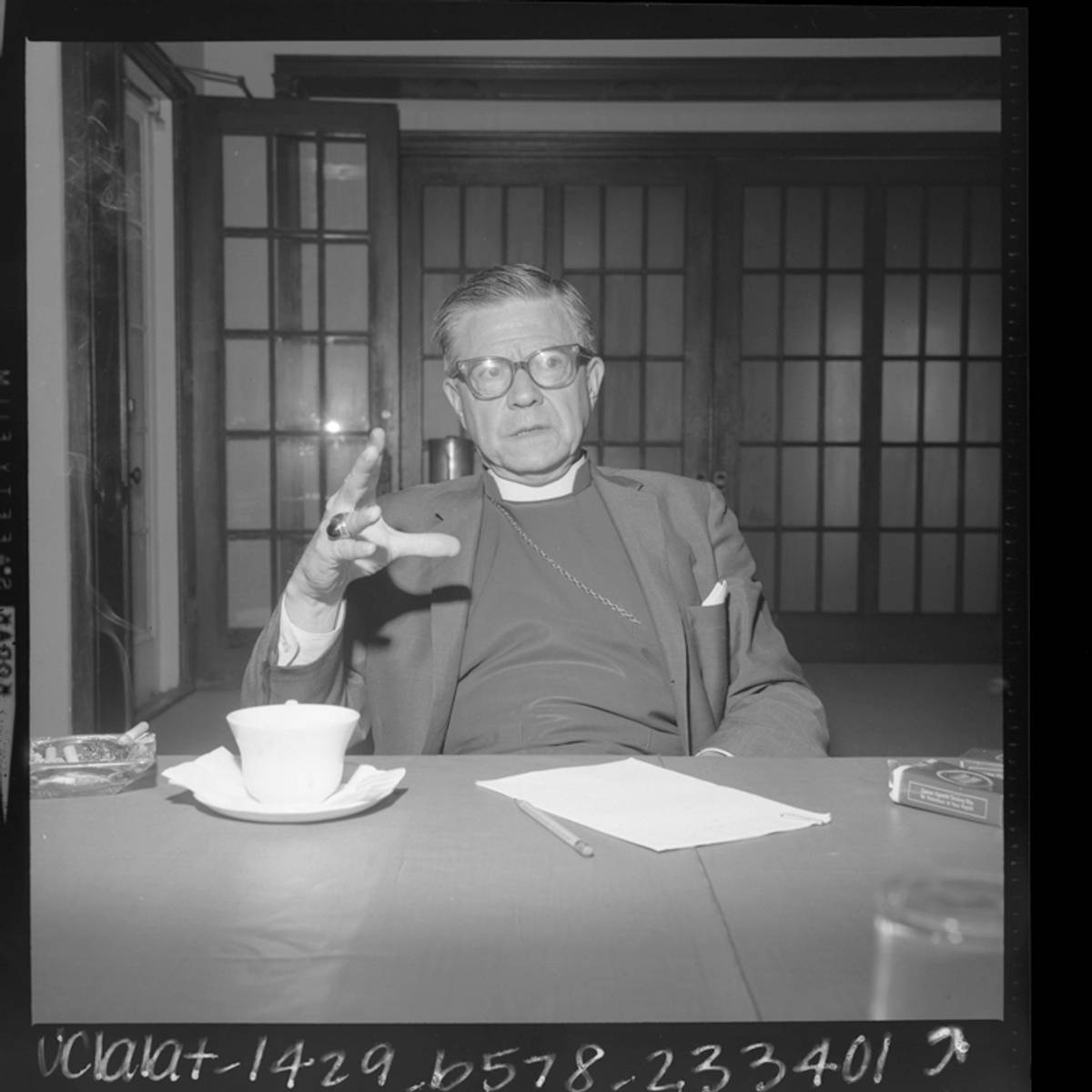

James Pike, the Episcopal bishop of San Francisco (the Timothy Archer of the novel), and Philip K. Dick formed a close friendship that began in the 1960s. They were a most unlikely pair. Dick, scruffy, paranoid, and addled by drug use, lived in bohemian squalor in rural California. Pike, obsessively neat, impeccably groomed, and very ambitious, lived in a magnificent residence in San Francisco. What they shared was a fascination with the occult, and with the Dead Sea Scrolls. Pike was an early advocate for civil rights, gay rights, and women’s rights. He was also an ardent Christian Zionist—a term that today conjures up Evangelical enthusiasts for Israel. But in the 1950s and ’60s it had a different valence: Zionism was supported by many liberal Christians, and Pike, like theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, was among the most committed American Christian clergy advocating for Israel. In the early 1960s, Pike visited Israel twice.

In 1965, Pike made his third trip to Israel. He invited his 20-year-old son, James Jr., to join him on that pilgrimage, which included a climb up Masada. Reflecting on that climb, Pike wrote, “I felt transported into a plane of hope where time is no longer significant and courage is the motivating force. It was a kind of psychedelic experience without drugs.” Pike said that for both himself and his son, the Masada climb tied them to Israel’s “heritage of courage and hope.”

In 1968, I was living in LA and experiencing California counterculture in all of its glory and vapidity. When I left California later that year, and went to live in Israel, a nation still basking in post-Six-Day War euphoria, I imagined that I had left the counterculture, the novels of PKD, and the ideas of Bishop Pike behind. I was mistaken.

In the summer of 1969, I was serving as a combat medic in the IDF. With a dozen other soldiers, I was stationed in a former Jordanian Army camp in the Judean desert. Early on a weekday morning the field radio operator told me that our commanding officer, who was traveling that day, wanted to speak to me, to “Goldman, the American.” With some trepidation I took the radio phone and heard him say that an American komer (Christian clergyman) and his wife were lost in our area of the desert. The clergyman was a VIP, and all efforts were being made to find him quickly—especially as the temperature that day was over 100 degrees.

Had I heard of this lost American, Bishop James Pike? the officer asked.

Yes, I said, he really was a VIP: The Episcopal bishop of California, host of a popular American TV program, and a name known throughout the United States.

“OK,” he said. “Now I see what the fuss is all about, I’m sending transport to you. Choose three men to join the area search. You have to stay at base with the unit.”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

The soldiers in my unit did not find James Pike. The following day a police patrol near Bethlehem was alerted to his whereabouts by his wife, Diane Kennedy. She told the police that after getting lost on a desert track, she and James went off in different directions in search of water and help. She had found her way to a police outpost; But Pike was lost. His body was found three days later. Wandering in the desert, Pike fell off a cliff and died. He is buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Jaffa.

A decade after Pike’s death, PKD was compelled to write a novel about him. The late clergyman was the subject of Joan Didion’s caustic essay, “James Pike, American.” Featured in her collection The White Album, the essay presented Bishop Pike as an exemplar of all that had gone wrong in the Golden State. “The man was a Michelin to his time and place,” Didion wrote. “He carried his Peace Cross through every charlatanic thicket of American life. ... The sense that the world can be reinvented smells of the Sixties in this country, those years when no one at all seemed to have any memory or mooring, and in a way the Sixties were the years for which James Pike was born.”

Dick may have been thinking of his friendship with James Pike when he said that he was embarking on another novel and wanted “to write about people I love, and put them into a fictional world spun out of my own mind, not the world we actually have, because the world we actually have does not meet my standards.”

The Transmigration of Timothy Archer is loosely based on James Pike’s life, disappearance, and death. It was written in 1981, the year before PKD died. The Library of America described it as “by turns theological thriller, roman à clef, and a disenchanted portrait of late 1970s California life.”

Dick’s portrait of the bishop is not a loving one. Rather, it is quite critical, though not as harsh as Didion’s. In the book, Timothy Archer travels to Israel to research the recently discovered “Gnostic scrolls.” He is convinced that these scrolls will reveal the secret origins of Christianity in their original Essene form. This quest leads to Archer’s search in the desert, and to his death.

The Israel that PKD was obsessed with both in his last novel and his diaries and letters, was the Israel of the second century BCE, not the modern State of Israel. But he was well aware of modern Israel and its diplomatic and military situation, and often expressed his opposition to Israeli military actions. In June of 1981 Dick wrote an impassioned and detailed letter to TV journalist Ron Hendren of the Today show. Hendren had defended the Israeli air strike on Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor. “I am a Quaker,” Dick wrote, and “I deplore military ‘solutions.’” Having stated his pacifist position, Dick frames his critique in political terms, rather than pacifist ones:

What Sunday’s air strike really boils down to—and I think you pointed to this in your commentary today, but perhaps only by implication—is that the balance of power in the Middle East must be kept in Israel’s favor in terms of nuclear weapons, since Israel is one small country surrounded by many hostile Arab countries. But it is Israel’s tragedy if she alienates world opinion and finds herself standing alone; she will have engineered the very thing she fears and suspects: an implacable, hostile ring around her, much as Germany experienced after World War One. The problem with paranoia in individuals and in nations is that it brings about the exact conditions that it suspects; paranoia is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Israel must not taunt the world with the fact that she is militarily capable of destroying any and all nations who might attack her because there is always the chance that this boast will be tested precisely because it is made.

For Dick, who was intermittently aware of his own paranoid tendencies, to accuse others of paranoia was a very Phildickian exercise. But that is what we might expect from a writer who said that his favorite joke was the story of the fellow who went to a psychiatrist and said that he suspected his wife of putting something in his food that made him paranoid.

Shalom Goldman is Professor of Religion at Middlebury College. His most recent book is Starstruck in the Promised Land: How the Arts Shaped American Passions about Israel.