Where’s the Semen?

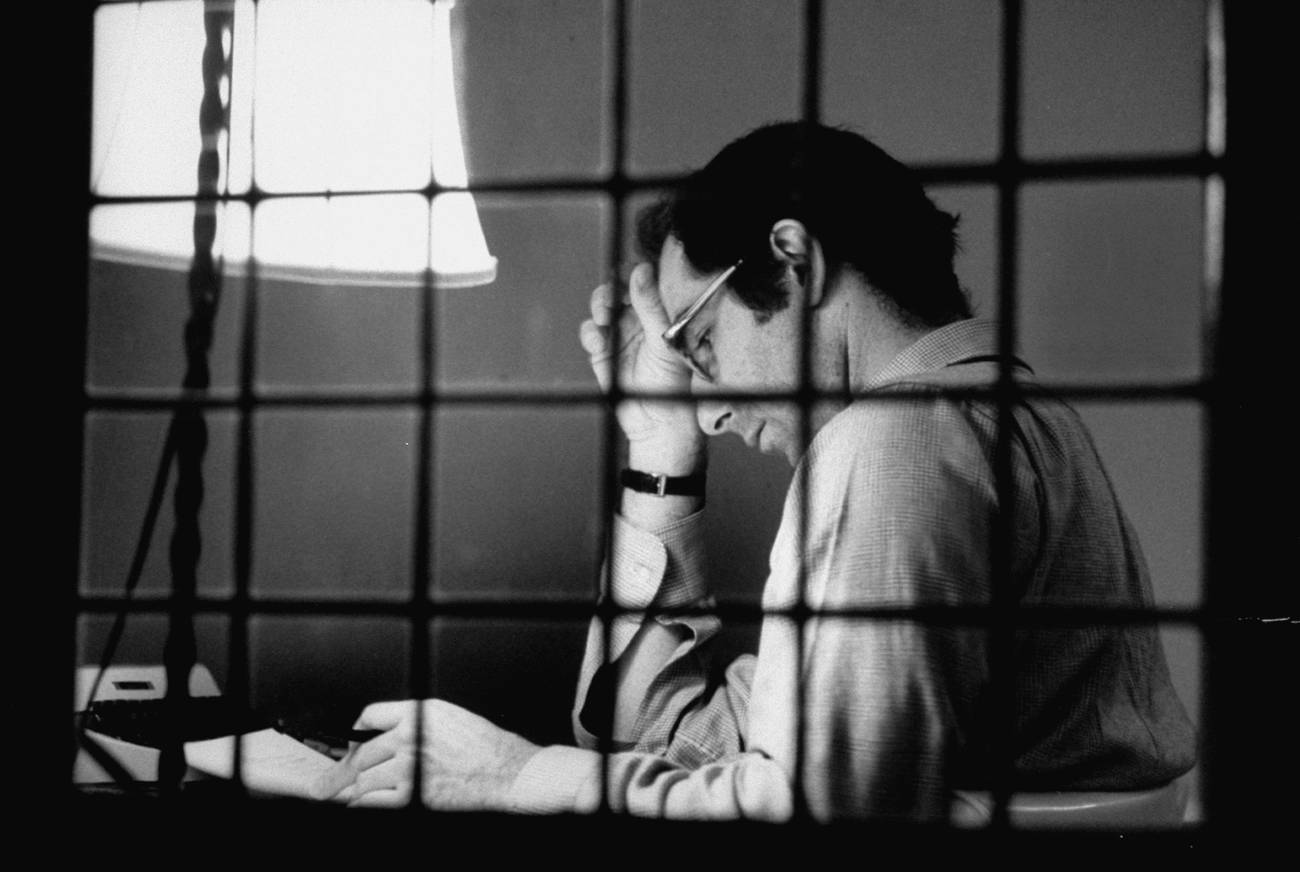

Blake Bailey’s Philip Roth biography finds neat patterns where there should be a mess

Philip Roth didn’t believe in an afterlife, yet he once predicted, with spooky accuracy, what would happen to him after his death. In his masterpiece The Counterlife, Roth gives Nathan Zuckerman a hero’s funeral, replete with fulsome tributes from friends and admirers. For once in his life/death, everyone loves Zuckerman. But at least one mourner is disgusted:

Where was the rawness and the mess? Where was the embarrassment and the shame?

Come on, he thinks:

Shame in this guy operated always. Here is a writer who broke taboos … and they bury him like Neil Simon—Simonize our filthy, self-afflicted Zuck!

This being Roth, the eruption continues:

This unsatisfiable, suspect, quarrelsome novelist, this ego driven to its furthest extremes, ups and presents them with a palatable death—and the feeling police, the grammar police, they give him a palatable funeral with all the … the mythmaking!

Everything in that delightful screed—vintage Roth!—stands out, has potency, but what really leaps out is the sharp word shame. The fighting, the screwing, the egotism—those we’ve seen; with Roth, we expect them. But when we read that “Shame in this guy operated always,” we hear a whispered—or shouted—confidence. We know we’re getting, as Roth so often did, to the heart of things.

Indeed, that was Roth’s unflagging mission, his raison d’etre, though his weapon was less the piercing aperçu than the frothing fulmination. The riff, the rant, the comic tirade—Roth virtually patented them. Is any writer’s voice as insistent, confiding, compelling? For 55 years, Roth needled, hectored, and inveighed: a prophet, a human geyser of talk. “It isn’t what it’s talking about that makes a book Jewish—it’s that the book won’t shut up,” he once said. In one novel, his hero suffers the worst possible fate. “I knew what I was doing when I broke Zuckerman’s jaw,” Roth said. “For a Jew a broken jaw is a terrible tragedy.”

Talk, talk, talk. Portnoy had his famous vice, but what he really couldn’t stop doing was talking. The point of Roth’s awesome outbursts wasn’t mere entertainment, or shock, but the telling of hard, blunt truths—more rude than crude. So it went for nearly every Roth novel. Harsh truths about society; about marriage; about Jews; about everything. “Old age isn’t a battle; old age is a massacre.” “The fantasy of purity is appalling.” “The heart of human darkness is inexplicable.” About the futility of understanding people, Roth was eloquent. Life is about “getting them wrong and wrong and wrong,” he wrote, “and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again.”

Which brings us, neatly enough, to Roth’s biographers, tasked with Getting Roth Right. In 2012, for reasons then unclear, Roth began auditioning biographers (Hermione Lee, Judith Thurman, Steve Zipperstein), eventually settling on Blake Bailey. As a biographer, Bailey specializes in self-destructive authors—John Cheever, Richard Yates, Charles Jackson. Roth, an abstemious sort, hardly fits this profile, but Bailey began conducting interviews and plundering archives. In his life, Roth tended to play the dominant role in friendships, seeking admirers and junior partners, a role Bailey performed eagerly in public. “He was one of the most decent men I have ever known,” Bailey said. That sounds humble and generous, but it should trigger alarm bells: Could Bailey be skeptical, clear-eyed, independent? Or would he become Roth’s Boswell? “I think Philip’s hope is that he would sort of write his own biography by proxy,” Bailey mused.

Nine years later, Bailey has delivered exactly what Roth wanted: a flattering portrait that smooths his edges, justifies his rage, trumpets his decency, and faithfully skewers his enemies. Oh, so many enemies! Most are “exes” of some sort: ex-friends, ex-lovers, a pitiful ex-biographer, the ex-chief-book-critic of The New York Times, and various critics Roth wanted to murder over the years. They get off easy, though, compared to the ex-wives: Claire Bloom, who apparently destroyed Roth’s life several times after Roth’s first wife, Maggie Martinson, had her cruel way with him, sparking murderous fantasies in the enraged, affronted Roth.

As it happens, murder is a leitmotif in Roth’s life: imagining it, craving it, and, surely, provoking the impulse in others. Very little, it seems, kept Roth’s life from spinning into a Patricia Highsmith novel at certain tense moments, all chronicled here. Roth claimed his life was boring—move along, folks, nothing to see here—yet Bailey proves otherwise. Murder aside, there’s rivalry, betrayal, and all the “higher gossip” you could want: mental breakdowns, legal crusades, affairs, eye-popping advances, every prestigious prize (except for The Big One), and a handwriting expert Roth hired to handle a situation too byzantine to go into (for all the messy details, see The Human Stain).

Bailey begins boldly: “Much of what Roth later wrote [after Portnoy’s Complaint] was in reaction to the mortifying fame of this book.” That’s true of Zuckerman Bound, less so, perhaps, of Roth’s other novels. But Bailey sticks to it: “Roth would earnestly come to wish he’d never published Portnoy.” Sudden notoriety left him rattled and besieged. “But then I finally beat them down,” he says of the critics who hated Portnoy’s Complaint. “Fuckers.” To Roth, much of life’s struggle was against various fuckers: hostile critics, like Michiko Kakutani; feckless publishers, like Houghton Mifflin; and his bete noir, biographers. Until meeting Bailey, Roth mainly despised them.

What kind of childhood produced such towering rage? The question looms over any discussion of Philip Milton Roth. Born in Weequahic, New Jersey, in 1933, the youngest of two brothers, he was raised in a tightknit Jewish family. The Newark Roths were working class, never poor, and the household was run exactingly and officiously. Bess Roth was a strict, efficient, somewhat inscrutable woman, not quite Sophie Portnoy, but not quite her opposite. A frustrated (and likely depressed) woman, she doted on Philip, but was also given to locking him out of the house as punishment, waiting until he broke down sobbing before letting him back in. The picture that emerges is an unreliable mother, adoring but anger prone, who could love or crush her sons depending on her mood.

Her foil as a parent was Herman Roth, an insurance salesman who climbed the ranks of Metropolitan Life as high as a Jew could go. As an adult, Roth worshipped Kafka, and no wonder: two sensitive Jewish boys with domineering fathers named Herman. Kafka’s father was a tyrant. Roth’s was a gruff, stubborn, abrasive sort who forcefully imposed his reality on his son. Without getting too Freudian, we can note that Roth spent his career clinging to his own reality, insisting on it. “I’m a realistic writer, concerned with the hard facts of life,” he once said, and admired other realists. “You look the worst right in the face,” he told Saul Bellow, who smartly returned the compliment: “Your capacity for looking things in the face is not inferior to mine.”

So youth was certainly no idyll. Bess and Herman may have lavished attention on Philip, but neither provided what the sensitive boy seemed to need: a reliable source of love and acceptance. Such love as they offered came with a price: strict control. As an adult, Roth would recall being smothered, while also feeling that he, who felt so deeply, didn’t quite belong to the family he was born into.

“Never again to feel such tender devotion—and a desire to escape,” Roth would write in The Anatomy Lesson, deleting the line from subsequent drafts.

And escape he did. First to Bucknell’s green but boring pastures, where he chafed against curfews, parietal rules, and the general prudishness of Eisenhower-era America; and then, when that wasn’t far enough, to the University of Chicago. Thus began a lifelong habit: fleeing one prison—home, school, marriage, fame—straight into another. For Roth’s heroes, serenity is boring—they love their messy, painful quandaries, and will never outrun them. “A life without horrible difficulties … is inimical to the writer,” says Maria to Zuckerman. As Roth himself noted, “I always seem to need to be emancipated from whatever has liberated me.”

Nonetheless, these were fruitful years, and formative ones; in some ways, they determined the course of Roth’s life. At Bucknell he encountered serious literature, devouring Kafka and Henry James (like all great writers, he was a great reader, but K. and J. remained his lodestars). He discovered the joys of satire, intellectual jousting, and, from professor Philip Wylie, cultural elitism. Wylie satirized philistine American culture, expanding Roth’s sense of the sayable (no small gift to a young iconoclast). This type of spectacle—verbal transgression in an adult—left Roth entranced.

And no wonder. The young Philip Roth was angry, excitable, and ambitious. He was also sensitive, nervous, and self-absorbed. And he was joyful company: a skilled comic, a natural mimic, with a specialty in Jewish voices. The label “Jewish-American writer” always rankled Roth—or so he insisted. Privately, he felt differently. It wasn’t just Bellow, Mailer, and Paley he admired, it was Howe, Fiedler, and Kazin, the Commentary crowd. “Shy as I was some months back about being grouped in with a bunch of Jews as a Jewish writer, I suddenly find myself willing to believe that this is something,” he told a friend. There was “a big change,” he reported; “I like to think that literature is being rescued from Nancy Hale and John Updike.”

Roth’s problems—and the biography’s—begin with Goodbye, Columbus, for which Roth won a National Book Award at the preposterously young age of 26. Here were all Roth’s Jewish voices—old and young, naive and shrewd, wealthy and working class—all humanly flawed. (Where did Roth get the audacity? Surely from Bess Roth, his earliest booster and admirer.) Bailey fails to grasp the book’s brilliance; in fact, his grasp of Jewish culture is pretty shaky. His references to tefillin, the “mitzvoh,” and Jerusalem’s “Orthodox Quarter” seem to come from Wikipedia, and his prose—specked with genteel flourishes—is never calibrated to Jewish subjects. Here, Roth’s uncles “sired” children (named Emanuel and Ethel!); Roth finds “sanctuary chez Brunstein” and has “dinner chez Amos Elon.” This is terribly off-key—we’re still in Cheever country, not Jewish Newark or Israel.

The chapters on Roth’s turbulent marriages are awkward in a different way. In the late 1950s, Roth met Maggie Martinson, a slim, attractive, deeply troubled mother of two. The relationship, never stable, would sometimes erupt, yet Roth seems to have trusted her—a rare occurrence in Roth’s life. The pair vacationed together; she edited his fiction. “M. and I are constant companions,” Roth told a friend, “talking, walking, being bored and irritable and pleased almost side by side.” Roth even blamed himself for their problems. “She is a rare person, truly … and if I were a little rarer, I’d not have soured things up so often.”

The portrait here, however, is largely retrospective: Roth looking back in anger. Bailey’s language can be exasperating: At various points, Martinson “snapped,” “snarled,” “erupted,” “hooted,” “burst out,” “berated.” Good lord—did the woman ever say anything? She certainly seems disturbed, but surely mentally ill people deserve more sympathy than this. Bailey managed a coup—finding Martinson’s diaries. But he quotes them mainly to impugn her rather than understand her.

Sure enough, Claire Bloom is portrayed the same way—in crude, depersonalized terms. Bloom is always bursting into tears; she weeps like a character in a Gothic novel. Bailey is happy to quote Roth: “suddenly Bloom was wailing and screeching and wildly running about the apartment.” Later, in the country, “her hysteria erupted in a curious way.” (That’s Bailey this time.) That’s Bloom’s M.O.: She wails, she flails, she decompensates. In one typical moment, she “threw her hands up to her face in horror, began to scream, and ran out of the house.”

Let’s be honest: The sexism here is pretty overt. Crazy wives do exist, but so do awful husbands, and Bailey might have considered how Roth’s cheating, his secrecy, his moodiness (“I know that I am a holy terror to live with if I haven’t been writing steadily”) affected his partners. In both marriages, he seems to have pushed already-fragile women over the edge. In Bailey’s harsh account, Bloom is an arch villain who can’t lift a finger to help her husband. “Almost every morning the spectral, trembling man would descend the stairs, and his wife would take one look at him and burst into tears.” This is the martyrology Roth propounded: “Boy Innocent, Bitch Guilty,” as Roth put it.

These are the weakest sections of Bailey’s book, and the least credible. The issue isn’t Roth’s feelings, which have their own validity, but his memories, so often warped by rage and self-pity. Now would be the time to admit that although I admired parts of this book, I didn’t always trust it. Over and over, I sensed Roth’s heavy hand guiding the narrative, boosting Roth, recasting history.

Why did Bailey, a seasoned biographer, follow Roth’s cues? In 2007, Bailey was asked about choosing a living subject. “I would have a hard time writing a single page without worrying what the consequences might be,” he answered, “and would almost certainly end up diluting the content somewhat.” In Philip Roth, one senses worry and hesitancy. When Bailey interviewed Roth, he was elderly, aggrieved, and somewhat paranoid. He was also, as Bailey admits, quite forgetful, apt to confuse his past with plots from his own novels.

That alone might be reason for skepticism. But Roth was also mischievous, an artful self-concealer. He spent decades fictionalizing his life, teasing readers, setting traps for professional Rothologists. (His memoir, The Facts, is listed as “fiction” by the Philip Roth Society.) Off-balance, Bailey quotes Roth with disclaimers: “so Roth claimed,” “as Roth vaguely recalled,” “to the best of his memory.” Elsewhere, he quotes Roth slavishly: “as Roth later noted,” “as he winningly admitted,” “One may argue, however—as Roth himself did …” Why the credulity? There’s a lot of stenography—and mythography—here.

Indeed, whenever I read something dubious—a marital spat, or the semifictional account of Roth’s Yeshiva University appearance—I checked the endnotes. Sure enough, there was Roth: a late interview, The Facts, or one of his unpublished manuscripts, Notes on a Slander-Monger and Notes for My Biographer, each designed to settle scores and protect his legacy.

A deep connection, which would have left him vulnerable, was intolerable. He couldn’t risk oblivion.

A shame. Here and there, we get glimpses of the excellent biography this might have been. When Bailey is good, he’s very good, a naturally gifted narrator of literary lives. He knows all the biographer’s tricks: sticking closely to lived experience; conveying what’s at stake; showing how the past acts upon the present (something most biographers forget). In his lives of Cheever and Yates, his main vice was messy, overstuffed chapters—what Leon Edel called “ill-digested masses of material.” But here, he writes sculpted paragraphs in smooth, unruffled prose. Most of all, he’s a charming, skillful narrator, which goes a long way in a 900-page book.

Naturally, he’s great at capturing Roth’s charm, that blend of confidence, eagerness, wildness, and playful sadism. A handsome man, rough but refined, with an alluring, unnerving intensity, he had no trouble finding bedmates. (From college students to Ava Gardner.) Not only a magnificent talker, he was, like all great seducers, a terrific listener, eliciting confidences, establishing intimacy (a one-way intimacy) quickly.

The charm could also vanish, leaving a void (“ice cold,” one writer branded him). I recall meeting Roth in 2012, a brief encounter, and watching Roth’s friendly expression tighten into a hard, suspicious glare. It was unnerving. Several years later, at the Jewish Theological Seminary, I watched a frail, red-eyed Roth accept his honorary doctorate, and was struck by how the light left his eyes when he stopped kibitzing and stared wordlessly from the stage while everyone sang “Hatikvah.”

Roth often seemed mystified by his contradictions, the many puzzling schisms in his personality. “How could I be both that and this?” he writes in Operation Shylock. “That” meant kindness, goodness, gentleness—the simple virtues. “This” meant wildness, rapacity. “Studious by day, dissolute by night,” says David Kepesh, defining what passes for a balanced life in The Professor of Desire. His moral counterpart is Zuckerman, plagued with moral envy. “It probably feels very good being so good,” he sighs—a poignant wish to be better than he is.

Dividedness is a metaphysical condition for Roth’s heroes, but it’s also a riddle: What made them this way? What might cure them? But good self versus shadow self is just the start; their divisions have divisions. “The fantasy of purity is appalling,” Roth wrote. But it was also appealing; like Zuckerman, Roth craved “Serenity. Simplicity. Solitude.” He wanted solitude—and companionship. Excitement—and stability. To assault society—and be adored by it. Alone, Roth was intensely self-critical (and self-aware). In public, he struck a closed, defensive stance: Never apologize, never explain.

With so many inner conflicts, a tranquil, contented life was never possible. Indeed, Roth often veered between extremes: “I’m becoming an old guy who seems to need his domestic intimacy more than he ever thought he would,” he marveled to David Rieff in 1987. Soon enough, those pleasures vanished in a mess of overlapping affairs. Roth had a gift for disrupting his own quiet existence, putting his “domestic intimacy” in jeopardy. Inside every stable person, wrote Rebecca West, is an arsonist who wants to “set back life to its beginnings and leave nothing of our house save its blackened foundations.” Roth’s inner arsonist was always reaching for his matches.

What limited Roth’s adventures was the need—powerful and insistent—to write, to create literature. Roth’s work habits were legendary; his discipline, astounding. But it wasn’t just manuscripts he obsessed over, it was book jackets, PR copy, the footnotes of his Library of America volumes. Always hovering, frequently disappointed, he fired agents, ditched publishers, replaced translators, rejected cover designs. Until the guillotine fell, these publishing people liked Roth, though Roth saw their relationships as transactional. His publishers “were management,” Roth once said. “I was labor. I didn’t trust anybody.”

At times, Bailey seems worried that Roth’s coldness, egotism, and lechery might repulse readers, and, as if to tilt the moral balance in Roth’s favor, provides an exhaustive account of Roth’s good deeds. We see lots of menschy Roth, visiting sick friends, though he was always taking notes, filing away details for his novels. “I am a thief and a thief is not to be trusted,” says the Roth character in Deception. There were enough jilted friends for a class-action lawsuit, from furious exes (“You stole my life!”) to fellow writers (James Atlas, Jonathan Brent, Saul Below). Nonetheless, Roth was fiercely loyal: When friends needed him, he showed up. When they didn’t, he showed up anyway.

Of course, there’s something suspicious about such overbearing generosity, which no one could refuse or reciprocate. It demanded recognition; it created an obligation. What comes through clearly in Bailey’s biography is Roth’s narcissism—his fragility and grandiosity, his guile, but most of all, his need to dominate. “There is a predatory side,” Ross Miller says of Roth and his brother. “… they are misogynist.” A striking vignette appears in Janet Hobhouse’s account of her affair with Roth: “he always listened like someone decoding, sensing, processing vulnerability, a place to enter, overpower …”

In light of that, certain mysteries of Roth’s character begin to make sense. Why the attraction to wounded, fragile women? Maybe it was psychodynamically complicated, but maybe not: Dominants seek submissives, narcissists seek admirers, and men who dislike women seek women they can easily dislike. Why all the womanizing, the loveless sex? Surely it was about control and domination, which he seemed to crave in every area of life. “I’ve needed sex in order to be indomitable, briefly deathless,” Roth told Benjamin Taylor. “Deathless” is pushing it, but “indomitable” gestures at something real.

Bailey might dismiss these conclusions; he tends to favor benign explanations over darker ones. Why did Roth marry troubled women? “From earliest childhood Roth had a soft spot for victims of injustice,” Bailey writes—which makes him sound like Louis Brandeis, not Philip Roth. “Roth would always have a weakness for vulnerable young women,” Bailey adds. Wait—who was weak? Seems like it was the vulnerable women, not Roth.

Over and over, Roth is cleansed and defanged (“Our filthy, self-afflicted Zuck!”). When Roth attacks critics, Bailey leaps to his defense: “Lest this seem excessively testy …” Did Roth sleep with students “procured” for him? “Well, it was a different time,” Bailey shrugs. Roth’s sexism? He’s just “fond of ribaldry.” Why not just say he liked offensively sexist jokes? “Rape and baseball: my favorite activities,” Roth told James Atlas after several Mets were accused of rape.

At times, Bailey and Roth seem to merge; Roth’s enemies become Bailey’s. Thus, William Gass is “a vindictive highbrow who resented Roth’s success”; Alfred Kazin is guilty of “generational testiness”; Irving Howe commits “exquisite sanctimony”; Norman Podhoretz is guilty of “humorless Jewish chauvinism,” which is to say, admiring Israel, as is “the angry Zionist” Marie Syrkin.

And on, and on. Ross Miller, Michiko Kakutani, Francine Gray—all Roth’s ex-friends and detractors are hauled out and scolded for their lese-majeste. This is a peculiar book, with a split personality of its own: Beneath the smooth, well-mannered prose, there’s a harsh, sarcastic edge; a spitefulness. Are there multiple Roths here? There are multiple Baileys as well.

You can forgive Bailey some of these sins. With Roth, you’re tempted to look away, or look selectively. Real rage—not the polished, theatricalized rage of novels—is frightening, as are deceit and manipulation. Bailey seems to know that, yet his attempt to sanitize Roth has a certain irony to it. Roth’s credo—“Let the repellent in!”—was firm and fixed: no poeticizing, no aestheticizing. No genteelisms, no euphemisms. As Roth once said, in an eloquent tirade, “We are talking about shit, honey, not everybody’s cup of tea.”

He was talking about language, but also appetite (two things at the center of Roth’s life). Inevitably, Roth’s biography is a story about ambition: thwarted, redirected, and finally realized. There were successes, failures, a long, swooping arc—Roth started as Lenny Bruce and finished as Samuel Beckett. In between were numerous switchbacks, each novel zigging where the previous one zagged.

After Goodbye, Columbus came Roth’s Serious Decade. “I wanted to be deep like Dostoyevsky,” he would say. “I wanted to write literature.” He succeeded, while failing to produce anything distinctive; quite clearly, his natural style was Dionysian, not Jamesian. Voila: Portnoy’s Complaint. “Enough being a nice Jewish boy,” cries Portnoy, speaking for his creator, while vowing to put the id back in Yid. In a single maniac performance, Roth overthrew shame, discretion, “and plain, old monumental fear.” Keeping faith with himself—his deepest, most uncivilized self—meant risking blame and opprobrium. “What’s to be done about that?” he once asked. “That the best thing you do is reprehensible?”

Of course, there’s something suspicious about such overbearing generosity, which no one could refuse or reciprocate. It demanded recognition; it created an obligation.

As Roth expected, his rude, raunchy, liver-defiling novel brought wealth and admiration. Yet Roth fixated on the criticism, the perception that he was wayward: a bad boy, panting after shiksas; a bad Jew, shaming the tribe. “I am sensitive to nothing in all the world as I am to my moral reputation,” says a Roth alter ego. So he was, and would remain. Readers teased him; rabbis scolded him; journalists misjudged him. A sense of siege took hold; it was him against the world. “He was somebody completely focused on one thing: survival,” his friend Judith Thurman said.

How to recover from sudden, unwanted fame? “Literature got me into this, and literature is gonna have to get me out,” Roth later wrote. It would, though not so quickly. After Portnoy, Roth lost his footing. His outstanding quality—that eruptive energy; that monumental life force—was channeled into mediocre works: The Breast, his attempt to outdo Kafka; Our Gang, a cynical book for cynical times, starring Richard Nixon; a loopy baseball satire, The Great American Novel. All landed with a thud, or a racket, vexing Roth’s new admirers. Bailey dutifully chronicles years spent “miserably picking his way between pitfalls of sentimentality and tastelessness.”

Bailey’s middle chapters address Roth’s profound discontent. “People don’t get older, they get enraged,” says an obscure Roth character. In fact, Roth cultivated rage: He nourished it, so it could nourish his writing. But he also suffered painful betrayals by people he trusted and admired. He was duped into marriage. His therapist, a vault of secrets, poured everything into a case study of a narcissistic “playwright” whose mother-rage poisons his relationships. Then Irving Howe, a former admirer, delivered a sucker punch: “The cruelest thing anyone can do to Portnoy’s Complaint is to read it twice,” he wrote. These successive body blows shaped Roth profoundly.

If there’s a single consistent theme in Roth, it’s how little we know, how unprepared for life’s rude surprises. “HOW COULD SHE? TO ME!” wails the Roth character in My Life as a Man (1974). Go ahead, Roth says, delude yourself; pretend you’re prepared; soon enough, you’ll be humbled. Real life is “Error. Error upon error. Error, misprision, fakery, fantasy, ignorance, falsification …” In that sense, we’re all victims, and Roth speaks to our human condition, if such a thing exists. “I don’t understand anything. I took a shower later, repeating those words,” he wrote in Patrimony. Among novelists, Roth is our great epistemologist, our laureate of ignorance. “That’s how we know we’re alive,” he wrote in American Pastoral: “we’re wrong.”

Of course, wrongness was only one idée fixe. Over the years, Roth’s eclectic obsessions included masculinity; the Jewish soul; suffering and survival; remembrance; life’s cruel, chaotic nature; the divided self; the individual versus the family; the individual versus society. Peering inside himself, Roth found whole universes (and grand, mythic themes—hubris, destiny, betrayal). By the 1990s, he’d perfected the trick of grafting personal obsessions onto large historical backdrops.

Private fears and dreads infuse The Plot Against America. Boiling rage at Claire Bloom fuels I Married a Communist. Roth’s sense of persecution drives The Human Stain, set during the Clinton impeachment. His sense of humiliation went into Swede Levov, fallen hero of American Pastoral. (Indeed, Roth’s novel cycle could be titled Humblings.) While looking outward, at America, Roth was always looking inward. He’d simply found the perfect historical correlatives for his private obsessions.

One of which—inevitably—was mortality. In Everyman, he famously wrote: “Old age isn’t a battle; old age is a massacre.” Actually, it’s even worse: Massacres end quickly, whereas dying takes forever, thanks to modern medicine. Between 1967, when his appendix burst at a party for William Styron, and the mid-2000s, Roth endured stents and surgeries, biopsies and defibrillators, winding up with enormous scars across his chest and legs. Who did that to you? one shocked lover asked him. “Norman Mailer,” Roth replied.

Bailey gives Roth a triumphant envoi, yet it’s clear that Roth’s final years were lonely, difficult ones. “Revenge is what I’m entitled to,” says one Roth character, and, likewise, his creator. “The appetite for vengeance was insatiable,” his friend Benjamin Taylor wrote. “Philip could not get enough of getting even.” In fact, Bailey gives us two portraits of Roth: an elderly writer living alone, nursing his grievances, and a literary champion, basking in awards and adoration. The grimmer image—a writer no longer writing, except for emails and long screeds—is probably truer to Roth’s overall experience.

Yet something remarkable happened in those final, desolate years. After a particularly awful breakup, Roth was “almost morbidly lonely,” Bailey writes. Indeed, one notices a sudden change: For the first time, Roth begins apologizing; he acknowledges dependence; he weeps. Something seems to have shattered in Roth, cracked the hard shell of his narcissism. “The tenderness was out of control,” says the narrator of Everyman. After 700 pages of Philip Roth, it’s stunning to watch his defenses crumble as a healthy regression takes place. Fully vulnerable—dangerously undefended—Roth begins “a ramshackle account of his life”; for once, he allows himself to write poorly; his lifelong perfectionism vanishes. It’s a fascinating, if easily overlooked, moment, one I never quite noticed until now.

There’s a tragic quality to Roth, who craved love and intimacy (indeed, his needs seem bottomless) yet consistently alienated and even punished the people who loved him. “I could be his Muse, if only he’d let me,” sighs the Maggie character in My Life as a Man. She gets it in the neck from Roth, savaged in novels and memoirs. “I believe, and I always will, that my place is with you,” Claire Bloom pleaded, only to be kicked aside (and accused of abandonment). Why did Roth choose solitude? Bailey quotes Jonathan Brent, who supplies what might be the book’s deepest insight. Roth is “lost,” he says, because

He lives in kind of an empty world. Not intellectually empty; not artistically empty; but in some deep psychic way. And it’s an emptiness he has cultivated very carefully. Because he can control that world. But it leaves him empty and I think he’s in great need of real love that he can’t find.

Within that empty, protected world, free of distractions and encumbrances, Roth could write alone. (“I’m huddled in my studio, where I really wish I lived,” Roth told Updike; “it’s all I ever wanted, more or less.”) Could it have been otherwise? As Roth sometimes said, he just couldn’t handle domesticity for very long. He was moody and mean—all that unsublimated rage spilled into domestic life. As Kepesh realizes, “I am so constructed as to live harmoniously with no one.” Elsewhere, Roth’s stand-in warns himself: “He who forms a tie is lost, attachment is my enemy.” A deep connection, which would have left him vulnerable, was intolerable. He couldn’t risk oblivion.

It’s possible to feel some sympathy for Roth. As we’re reminded here, every howl of rage was a howl of pain, and Roth’s suffering was as great as the suffering he inflicted. As Roth himself said, “you see the suffering that real rage is.” That rage, that life force, was both blessing and curse—hugely generative, awesomely destructive. “You want to be his friend? Good! Go and be his friend,” someone close to Roth told me. “But you wait—ha, ha, ha, you wait awhile! It’s gonna get smashed. Because that’s what he does. That’s him.”

What’s to be said in the end? Biographers, like detectives, seek patterns; with Roth, the deeper patterns are often hidden. From one angle, Roth is a loyal friend, deeply generous, whose ardor and virtue are Achilles’ heels. If you look differently, shifting the focus and broadening it, you get a much darker portrait of an aggressive, cunning man who needs to dominate people; who loves women but also hates them (“Rape and baseball: my favorite activities”), who needs to vanquish enemies (“to prevail”), who values friends but also exploits them (“I don’t know why anybody has anything to do with me”), who turns his fury into comedy (“Shouting is how a Jew thinks things through!”), but who is, at heart, a narcissist, with a hollowness at his core (“I, for one, have no self”). Blake Bailey is determined to see benign patterns, yet he also reveals, through sheer accretion of detail, the darker ones. Was he deceived? Bewitched by that confident, beguiling voice? If so, he’s in good company. “The man gives nothing. (Yes, except to literature),” Janet Malcolm concluded after 20 years. “He is completely selfish and manipulative. How taken in I was.”

But let’s grant Roth the final word. In his novels, Roth left guidelines for every biographer who might let sympathy cloud his judgment. A writer’s essence is impurity, caprice, venom, obsession, childishness, he wrote; no “pious memorial” would do. “We leave a stain, we leave a trail, we leave our imprint,” he says in The Human Stain. “Impurity, cruelty, abuse, error, excrement, semen—there’s no other way to be here.”

Jesse Tisch is a writer, editor, and researcher. He lives in New York City.