The Philip Roth Archive

A fan’s obsessive rummage through the letters and papers of the writer who died two years ago today reveals a playful, funny, brilliant man

Philip Roth was 23, fresh out of graduate school and the Army, when he began wooing The New Yorker in earnest. Several years earlier, he had pitched the magazine a story (“and I’d just as soon forget about that,” he admitted later). When the inevitable rejection came, Roth licked his wounds and tried again. And again, and again. There were rave rejections, terse rejections, a few acceptances, as Roth established his reputation elsewhere. Ever hopeful, Roth pitched a section of Portnoy’s Complaint—his finest work, he thought. His editor disagreed. “I’m awfully sorry,” the man replied, returning the manuscript to Roth’s agent. The story was shapeless, and, worse, uninspired. “It’s basically pretty familiar,” the editor sniffed. Thanks, Mr. Roth. Please try again.

I’m a Philip Roth fan from way back, not a completist—someday I’ll finish When She Was Good—but pretty close. That Roth suffered the typical young writer’s fate—frustration, unsuccess—came as news to me when I began poking around Roth’s archives. Indeed, surprises abounded. His complex friendship with John Updike. His remarkable generosity to younger writers, whom he supported and encouraged—all quietly, without any fuss. Roth even let one penurious scribbler squat in his studio, rent free, for several months.

How well do we know Philip Roth? Too well? Or not well enough? Roth’s 27 novels, so personal seeming, are arguably the greatest source of a certain kind of information about Roth: his obsessions, his defenses, how he processed the world. But that tower of fiction is only a fraction of Roth’s writing. Like many authors, Roth has a hidden oeuvre, the scattering of letters, notebooks, and drafts whose existence is known mainly to archivists. To the curious, they’re irresistible, a vault of hidden knowledge promising closer contact with Philip Milton Roth.

Exploring Roth’s papers, reading his private letters—neatly typed, carefully punctuated, packed with pungent humor—felt nothing like normal archival sleuthing. For starters, it’s almost impossible to be bored in Roth’s company. In the quiet, claustral atmosphere of reading rooms, Roth’s playful and uproarious letters had me cracking up. Roth’s singular voice, that thing which “begins at around the back of the knees and reaches well above the head,” as Roth’s alter ego, Nathan Zuckerman, put it, was ever present, clear and compelling as the voice in Roth’s novels.

At times it was like eavesdropping on the liveliest book-chat I’ve ever heard. At times, like a visit to slightly deranged dentist. The exuberant Roth, playful and profane, was frequently present, but so were his many doppelgängers. The sane and civilized Roth, a font of wry, erudite banter about authors. A slightly unhinged Roth, spouting a kind of mad sanity about society’s bogus conventions. And the wrathful Roth, cursing moronic reviewers and feckless publishers. Writers contain multitudes, but few were as multitudinous as Roth. For every life, a counterlife. For every Roth, a counter-Roth.

There was also, among those numerous Roths, a troubled and tormented Roth, prone to rages and depressions, whose inner conflicts made life nearly unbearable. A Roth, in other words, like a distraught character from a Philip Roth novel.

Roth’s biography may be familiar in its outlines: a tender if claustrophobic childhood in Weequahic; an unhappy year at Rutgers, then a harried escape to Bucknell University; a grand literary debut in 1959, followed, 10 years later, by the grander success of Portnoy’s Complaint.(In between, Roth went quiet, writing two well-mannered novels in thrall to Henry James.) Roth was uncomfortably famous after 1969, and, seeking refuge, bought an old farmhouse in Cornwall, Connecticut, where he spent half of the next 46 years. Roth was married twice—peacefully, then tumultuously, to Margaret Martinson, and then to Claire Bloom, whom he followed to London in the 1970s. When England’s charms wore off (“I feel like I’ve been a P.O.W. in London for 11 years,” he told John Updike), Roth left the country, and, soon, Bloom. Roth’s final decades, before his 2011 retirement, were almost staggeringly productive, ensuring his place among the exalted postwar novelists: Bellow, Updike, Morrison, DeLillo.

Roth’s ambition and confidence were evident early. In August 1956, Roth met William Shawn, the quietly formidable New Yorker editor, and handed him a story, “Conversion of the Jews.” It was a friendly if awkward meeting, as a letter in The New Yorker archives attests. Young Roth was flustered; Shawn wondered if Roth considered himself “too avant-garde” for his magazine. Roth recovered. He wrote hopefully to Shawn that September—had the editor, by any chance, read his story? “I would be most interested in your comments, if you would care to make any.” As for the charge of being avant-garde: “what I wanted to say, I think, is that I like to think of myself as not avant-garde, or rear-guard, or New Yorker, or Partisan Review, but as Myself.”

Fear of being misunderstood—misread, misjudged—plagued Roth for decades, and it’s striking to see those worries present so early. The 20-something Roth was anxious, but canny enough to make his anxiety disarming. “At the risk of sounding like a nervous writer, I want to suggest an ad in the New Yorker,” he wrote his publisher, Houghton Mifflin, showing characteristic assertiveness. Judging by his letters, Roth was anxious about almost everything, from writing (“I want to work, but it’s frightening”) to the sight of idle expats (“make me nervous; they don’t work enough”) to money (“I hate to depend upon my writing for my living”). It was the plight of “basically nervous types like us,” he told Ted Solotaroff, an early friend and confidant, to back out of literary arguments.

Even then, literature was Roth’s life; he was one of the lucky ones who discover his calling early. Of course, writing was also difficult, almost impossible. “Frankly, I hate to work on anything—especially this novel, which is tough and tricky—at a too lively speed,” he told his editor in 1958 (the novel would be scrapped). So it would remain for decades. Producing a novel, for Roth, was a gradual, almost glacial, process, rife with false starts and endless revisions. Few writers produced as much brilliantly polished prose as Roth, but few tossed out as many reams of manuscript. Within Roth’s oceanic archives at the Library of Congress—the first port of call for many Roth researchers—is a mountain of discarded drafts, a testament to his lifelong graphomania and his stubborn perfectionist streak.

I was lucky. I had a job that required frequent travel, and thus provided what I thought of as free research grants to cities with excellent archives, where, with the help of patient archivists, I found a smattering of Roth’s letters and manuscripts. Planning these side trips was simple—call ahead, schedule an appointment, request materials online. Bring a laptop, camera, and an air of seriousness. Planning these expeditions around work junkets added a frisson to the experience. This may not be how Robert Caro does his research, but for me, it worked just fine.

I was curious about Roth’s methods—how real life was molded, transmuted, into narrative art. Roth loathed the C-word—confessional—and bristled at accusations of autobiography. He was writing fiction, he always insisted. Nevertheless, his letters reveal how cleverly and omnivorously he exploited personal experiences. It all went into “that great opportunistic maw, a novelist’s mind,” he wrote in The Human Stain. Everything was material. What doesn’t kill you becomes grist for your next novel.

One source of material was other novelists. Recall the sentence quoted earlier about a writer’s distinctive voice? It was written by John Cheever, in a letter to Roth, and copied verbatim into The Ghost Writer. With similar audacity, Roth turned Saul Bellow into the vain, oft-married Felix Abravanel (“alimony the size of the national debt”). But neither author gave Roth an entire novel; that distinction went to Irving Howe, who famously retracted his praise of Goodbye, Columbus in 1972. The following year, in an act of profound chutzpah, Howe asked Roth for a favor—an editorial supporting Israel. The whole contretemps, including Roth’s furious three-page reply, went into The Anatomy Lesson, where Howe is “Milton Appel,” a shrill, sanctimonious critic.

“Borrowing” is the writer’s prerogative, but I wondered if Roth felt any qualms about cannibalizing the lives of friends, girlfriends, ex-wives. “I am a thief and a thief is not to be trusted,” says the Roth character in Deception. In his letters, Roth was thoughtful but unapologetic about his borrowings. “The ethics of disclosure—no easy answers,” he wrote Solotaroff in 1983. “Great pain. But disclosure IS WHAT IT’S ALL ABOUT. IT’S WHY WE LIVE. DISCLOSE IT. TELL IT.”

I thought about Roth’s injunction in the archives, and later, as I contemplated writing about Roth. “Disclose it. Tell it.” Those words should be emblazoned above any researcher’s work desk, along with “Be skeptical” and “Verify.”

“But it’s awful to do it,” Roth added a moment later—“it’s just fucking hideous.” Research is exciting—secrets lurk in letters and diaries, and the thrill of discovery is intense. And yet, a feeling of moral queasiness is hard to avoid. Rifling through an author’s archives, we can easily imagine our own cherished privacy being violated—our letters read, our secrets revealed. Karmically, it seems unwise.

Feeling sympathy for your subject, even while violating his privacy, is part of the peculiar experience of archival research. So I thought while reading Roth’s candid early letters (now browned and flaking) about his aloof mother and abrasively stubborn father. This wasn’t the family Roth remembered in his memoirs, nor was it the “intensely secure and protected childhood” he claimed for himself in Weequahic—“a serene, desirable, pastoral heaven.” Nostalgia, of course, is both a love for the past and a contempt for the present, and I started to wonder about Roth’s state of mind in the late 1980s, when he wrote those memoirs. It couldn’t have been an easy time for Roth—and, indeed, it wasn’t.

Roth suffered serious depressions in 1987 and 1993. “Depression is a misnomer,” he wrote Solotaroff in October 1993. He had been virtually incapacitated. “I’ve never known anything like it. … It was terror, inexplicable, persistent, and overwhelming, and instead of going away it got worse and worse.” The grim experience overlapped with, and perhaps precipitated, the collapse of his 17-year relationship with the actress Claire Bloom. In Roth’s letters to Bloom—a bundle of which were retrieved from Boston University’s archives and ceremoniously unsealed by an archivist—trace the arc of their relationship, from an early, avid courtship to a Grand Guignol conclusion. Here was the miserable, paranoid Roth, eager to punish Bloom for her supposed perfidies and reclaim every last dollar he had given her. “It comes to over $400,000,” he wrote Bloom in the fall of 1993. “Just send a check.” With a vindictive flourish, he demanded $62 billion, one for each year of her life.

Setting the Bloom letters aside, I soon moved to a less fraught, but no less fascinating, collection that included Roth’s letters to Irving Howe. Reading the Roth-Howe exchange about Israel, I tried to imagine Roth’s unwritten editorial. Roth was hardly a Middle East expert, but what he lacked in knowledge he made up for in enthusiasm. Roth was fascinated with Israel—“a whole country imagining itself, asking itself, ‘What the hell is this business of being a Jew?’” he wrote in The Counterlife. Roth’s two Israel novels feature numerous voices, a Jewish jamboree, but the one voice conspicuously missing is Roth’s. While shuffling from archive to archive, I wondered what I might find about Roth’s personal politics.

In the quiet, claustral atmosphere of reading rooms, Roth’s playful and uproarious letters had me cracking up.

Answer: not a whole lot. Roth visited Israel several times, first in 1963, for a conference on Jewish identity, and again in the 1980s. “The country played a significant role in my imagination as a writer—in a good sense,” he once said. From the moment Roth arrived, he was bewitched. “The Holy Land is real and full of Jews,” he reported to Solotaroff, marveling at the simple fact of being surrounded by Jewish policemen, truck drivers, and dishwashers. Twenty years later, Roth discovered a vastly different Israel with many of the same charms. “I lead a tidy life, but have a strong taste for disorder and its excitements, and there’s plenty of that there,” he told Solotaroff. Passions ran high; everyone had six opinions; the political stakes were stratospheric. “It’s what Prague was to me in the early ’70s—finally a place where everything matters,” he told Solotaroff. In some ways, it was the antidote to American culture. In Israel, Roth escaped “the trivialization of everything that I keep feeling back home.”

For all of Israel’s excitements (“It’s like the ’60s there all the time”), the country’s political battles didn’t captivate Roth. His letters are almost bereft of references to Menachem Begin, the Knesset, and the Israel-Palestine conflict. Instead, he veers persistently toward the American scene. Roth’s politics can be opaque; he seems to elude the classic categories of liberal and conservative. Yet Roth’s letters reveal a motley of passionate, heterodox opinions, of eclectic likes and dislikes.

Like H.L. Mencken, he felt a reflexive contempt for sham, hypocrisy, and philistinism. Unlike Mencken, he took no delight in the grotesque American spectacle. He couldn’t stand “pricks like Nixon running the dignity of the place into the ground,” he told Solotaroff. Roth’s response to Vietnam was to propose a nationwide protest of professors. (“The idea is to shut down as many of the universities in America as possible,” he wrote Robert Silvers, pitching the quixotic but earnest idea.) Roth’s anger and anguish, his sadness at seeing American ideals trampled, traduced, betrayed, come through in many of his political letters. Roth often sounds furious. But he also sounds heartsick.

He reacted to personalities as much as policies. Donald Trump was “a massive fraud, the evil sum of his deficiencies.” George W. Bush was “a real putz,” more hapless than malevolent. The elder Bush—“a fake without any redeeming characteristics”—was almost as odious as Gerald Ford, whose pardon of Nixon displayed “moral ignorance, blundering authority, and witless, arbitrary judgement.”

Roth saved his greatest contempt for “smilin’ Hitler,” Ronald Reagan, whose election marked the nadir of “media stupidity and cynical commercialism.” There was something sinister about his vacuity, Roth thought—a hidden malevolence. When Reagan visited Bitburg cemetery, where 2,000 Nazi soldiers were buried, Roth was incensed. “His moral and historical ignorance is hardly surprising but appalling nonetheless,” he wrote Elie Wiesel, applauding Wiesel’s “strong, outspoken opposition” to Reagan’s outrageous decision.

Though consistent in his loathing of Republicans, Roth was hardly a right-thinking liberal. By temperament, he was a cultural conservative, a proud elitist who found American culture debased and philistine. (In his interviews, Roth can sound

like Alan Bloom raving about “the threat to a civilized America” and “the intellectual situation for thinking Americans.”) Roth was disdainful of all political orthodoxies: If one wanted complex, nuanced truths, one went to literature, not the dumbed-down realm of politics. There, one found pieties and platforms, distortions and simplifications.

Roth was a serious secularist, an ardent disbeliever. “I have no religious turn of mind, none,” he wrote Solotaroff in 1985, rejecting his reverent criticism (“Here we belong to different minyans”). Roth’s contempt for religion seemed to increase over the years, turning quite strident, but he also had a sense of humor. “When God wants to say fuck, he says it through me,” Roth jotted on a Post-it note in his archives.

Roth’s hostility to political correctness, his target in The Human Stain, was intense. Must we be “nice” all the time? Must we censor offensive thoughts? When the scholar Edward Hoagland was accused of homophobia, Roth was furious. “Talk about dull and predictable, not to mention narrow, puritanical, philistine, wrongheaded, hysterical, dogmatic, prescriptive, and humorless—enough to be consigned to Hades in a world where there was any human justice,” he raved to Janet Malcolm. “It is old-fashioned American philistinism, idiocy in the face of any complicated human utterance, terror of irony, comedy, satire, criticism, etc—AND FUCKING SELF RIGHTEOUSNESS.” For her part, Malcolm was surprised by Roth’s ferocious outburst. “Why are you yelling at me?” she responded.

One of Roth’s favorite themes was dividedness; his novels offer a typology of clashing selves. The guilty vs. free self. The calm vs. anarchic self. The humble vs. self-dramatizing self. Roth may be our laureate of inner conflict, and not just for Portnoy’s Complaint. His great novel Operation Shylock (working title: Duality) is a case study that might be titled The Chaos of Conflicting Desires in a Completely Un-integrated Personality. The book’s epigraph sums it up: “the whole content of my being shrieks in contradiction against itself.”

On occasion, Roth divided his oeuvre into two shelves by two different authors. “Good Philip” (as we might call him) was well-behaved—“sane and brainy and generous.” He wrote civilized novels that everyone could embrace without being pricked or unsettled. Novels like The Ghost Writer and The Counterlife.

Philip #2 was his rowdy doppelgänger. He wrote caterwauling novels like My Life as a Man and that great comic conniption, Portnoy’s Complaint, the kind of book that, as Roth once put it, “won’t leave you alone. Won’t let up. Gets too close.”

Which Philip was the real Philip? The one closest to Roth’s core?

“I like that you like me most … at my most demented,” Roth wrote Gore Vidal in 1975. “I’ve been dying to hear somebody say that for years—and it pleases me no end that it was you.”

Yes, he acknowledged, some readers preferred quiet, virtuous Philip to his Dionysian opposite. But he didn’t have to like it. “I’m starting to despise the fact that these people like the book,” Roth told his editor, David Rieff, after The Counterlife was published. “That’s what their fucking approval is all about,” Roth fumed. “They can shove it.”

Roth’s letters capture other divisions, other polarities. After a decade living with Claire Bloom, Roth seemed settled and content. “I’m becoming an old guy who seems to need his domestic intimacy more than he ever thought he would,” he wrote Rieff in 1987. It didn’t last. Soon Roth was craving excitement, plunging into affairs, disrupting his own quiet existence. Roth seemed to seesaw between extremes—calmness and chaos—without a default setting. Roth was “too apt to fall in love,” Benjamin Taylor writes in his recent memoir of Roth. “Then, having fallen in love, he needed to escape from the presumed monogamy that love entailed.” By the evidence of Roth’s letters, that pattern persisted throughout his life.

Roth’s relationships with women will surely get exhaustive treatment in forthcoming biographies. So will the misogyny in his novels, but those conversations have always tended to be simplistic. In some ways, Roth turns gender stereotypes around: Roth’s men, with their operatic problems and refusal to ever shut up about them, conform to the female stereotype of being overemotional, while Roth’s women, notably Drenka, in Sabbath’s Theater, are every bit as vulgar, appetitive, and reckless as the most archetypal males. Not all Roth’s women, of course—there are too many castrating wives, screaming harpies, and barely legal sexpots. They may have agency and desires, but they’re seldom as intelligent or well-rounded as the men.

Roth’s feelings about feminism were conflicted. He resented accusations of misogyny (“the flaw in my humanity which is rapidly replacing the anti-semitism that critics used to worry about so,” he wrote John Updike in the late ’70s). It was silly, he often said—how could he generalize about half the world’s population? Once, after hearing himself called a “male chauvinist pig” on the radio, Roth vented his anger to Solotaroff. Hadn’t anyone read Letting Go? He had written it to “blatantly demonstrate the misery the women are now speaking up about!”

Roth’s letters aren’t free of casual sexism and crude comments about women. “We’re entirely too lax with ours,” he told James Atlas after a trip to Morocco. “You don’t realize how many pounds of fire wood a woman can carry on her back until you see it with your own eyes.” Yet a respect for the feminist movement also comes through. Roth deplored the anti-feminism of England’s Spectator magazine, and he supported second-wave feminism’s demand for autonomy and independence. In less defensive moments, he considered himself a sympathetic ally. In crankier moments, he deplored the stridency and hollowness of feminist rhetoric.

There is misogyny—no getting around it—in Roth’s novels, yet it can be hard to differentiate from a more generalized misanthropy and a jaundiced view of coupledom. If you think Tinder ruined romance, read Roth and take heart. “Dating is hateful, relationships are impossible, sex is a hazard,” a woman complains in The Dying Animal. “The men are narcissistic, humorless, crazy, obsessional, overbearing, crude, or they are great-looking, virile, and ruthlessly unfaithful, or they are emasculated, or they are impotent, or they are just too dumb.”

Reading Roth’s published interviews, I often wondered just how trustworthy Roth was on the topic of Philip Roth. A sly spirit infuses Roth’s memoir, The Facts, which offers a completely plausible portrait of Roth’s early adulthood … and then debunks it, or complicates it, with a mischievous coda.

Reading Roth’s letters, you realize—surprise, surprise—how boldly and mischievously Roth rewrote personal history. While making whistle stops on the Roth trail, I sometimes thought of Dylan, Whitman, Springsteen—our great American self-mythologizers. There’s some evidence that Roth belongs in their wily and audacious company.

Take Roth’s account of the Yeshiva University fracas of 1962. The young Roth, still comfortable in public, had appeared on a panel, “The Crisis of Conscience in Minority Writers of Fiction.” Roth recalled the event in the most dramatic terms: an attack verging on an auto-da-fé. The large audience accused him of ethnic treason, of anti-Semitism: Would he write similar stories in Nazi Germany? Roth tried to protest—“But we live in the opposite of Nazi Germany!”—but was drowned out. Beholding the melee, his fellow panelist Ralph Ellison tried to intervene, asking, “What’s going on here?” When Roth attempted to leave, angry students circled him, screaming “You were brought up on anti-Semitic literature!”

The yeshiva fiasco has a prime place in the Roth mythology. “That night at Yeshiva was a slaughter,” David Remnick wrote. Actually, it wasn’t. The event was civilized; the crowd, appreciative. Roth arrived primed for battle—he would “take the smug bastards on,” he told Solotaroff, referring to the event organizers, and though he expected “a lot of shit from the audience,” he planned to return fire. The first half of his plan went smoothly. “A good part of Mr. Roth’s speaking time was devoted to an attack against detractors of his work,” the student newspaper reported.

But the audience wouldn’t be baited. The event proved uneventful; nearly all the assaults happened in Roth’s imagination. Clearly, Roth needed this—the trauma that stoked his anger; the anger that fueled his writing. As Roth once put it, “A writer needs his poisons”—the stimulating angers that set his pen in motion. Roth’s enemies, those unwitting muses, certainly stoked Roth’s anger, but they couldn’t do it alone. Some of Roth’s “poisons” were self-administered.

The art of cultivating enemies is on display in Roth’s early letters. I took my shortest research trip—three subway stops on the 5 train—to the 42nd Street branch of the New York Public Library, where Roth’s letters to The New Yorker were waiting on a tall metal cart. The tempest over Roth’s 1959 story, “Defender of the Faith,” prompted Roth to request all the angry letters The New Yorker received. Roth’s editor balked, fearing they would damage the young writer’s psyche, but finally relented (“I’m still not sure that you’re wise to ask to have them,” he sighed). Years later, Roth would recall his persecution by hostile readers and rabbis, but the truth was, Roth had their number. “I’m being accused of anti-semitism,” Roth informed his publisher after Goodbye, Columbus came out. “I wonder if it might not be profitable to pour some gas on the fire,” he added, suggesting an advertisement in The New Yorker, where his detractors were bound to see it.

On the subject of enemies, Roth added a grace note in his memoir. “They boo you, they whistle, they stamp their feet,” Roth wrote; “you hate it but you thrive on it.”

Roth hoodwinked everyone, including his biographer, with his tale of ravening Yeshiva University students. How many other tall tales were foisted on unsuspecting journalists? The allure of authors’ letters—apart from the voyeuristic thrill of eavesdropping on a private conversation—is the illusion of honesty and intimacy. Here, we think, is the author himself, open and unguarded. Reading Roth’s letters offers an additional frisson because of Roth’s penchant for secrecy and disguises.

Of course, the illusion is just that: an illusion. Letters are a performance, too, despite the appearance of artlessness. It was a performance that Roth sometimes grew tired of. “I hope this wasn’t insufficiently droll,” he told Atlas in one particularly sober letter. “I know what you expect of me, but I just can’t keep that going day in and day out.” Like all performers, Roth felt obligated to be entertaining.

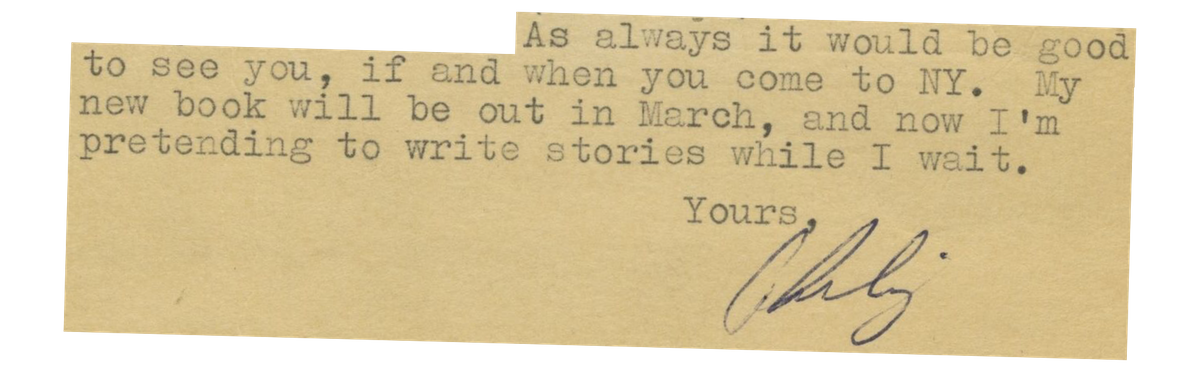

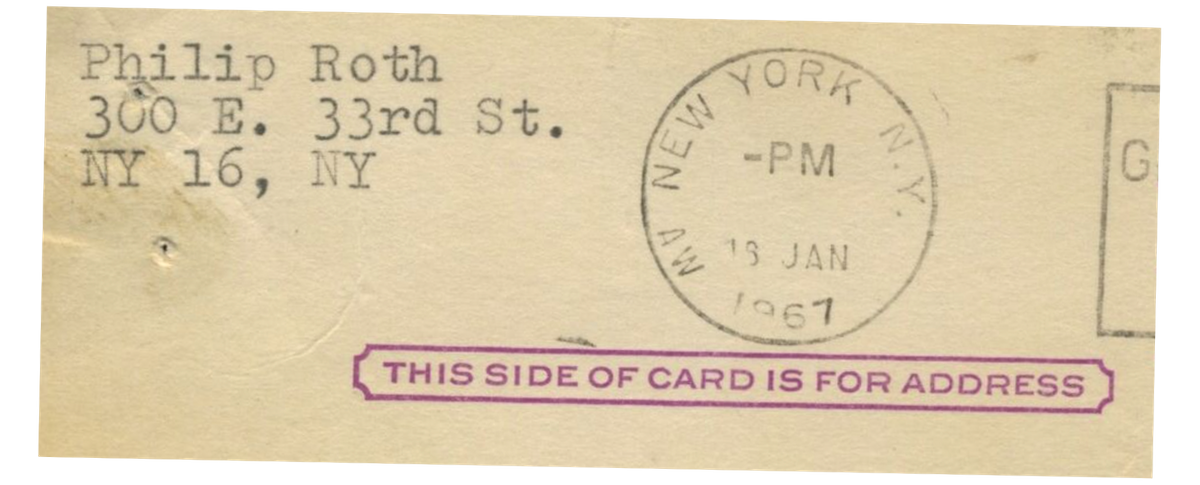

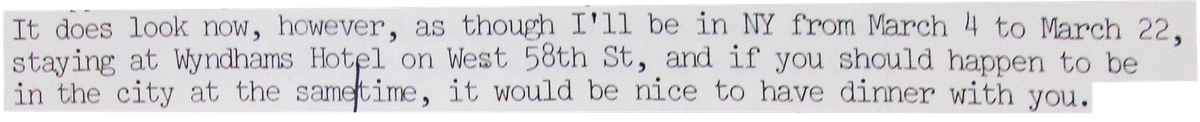

Both of those qualities—drollness and sincerity—characterize Roth’s letters to John Updike, which reside at Harvard, Updike’s alma mater. Conveniently, so do several other collections in which Roth makes a cameo—the Gore Vidal collection and the Houghton Mifflin collection, the latter offering a rare peek at the pre-famous Roth, circa 1958. At the time Roth was a fledgling enfant terrible, while the precocious Updike was writing Rabbit, Run, the first in his celebrated cycle.

Reading Roth’s letters, you realize how boldly and mischievously Roth rewrote personal history.

Their relationship is hard to categorize, not a friendship, exactly, nor merely an acquaintance. For all their similarities—two literary grandees of the same generation, both precocious, prolific, obsessed with male desire and waning potency—they were strikingly different. Religious and secular. Serene and intense. High style and vernacular. Whereas Updike poured out novels, Roth, a plebeian laborer, assembled them brick by brick. To say that writing was pleasure for Updike and torture for Roth is to overstate things only slightly.

The Roth-Updike letters reveal a deeper, more complex relationship than I had known about. Despite their differences, Roth admired Updike extravagantly, both as a novelist and a critic. “There’s no other writer (which is to say no one at all) in America whose high opinion means more to me than yours,” Roth wrote Updike in 1988. Roth pored over Updike’s reviews of his books, taking them to heart even when he didn’t agree: “take a look at page 181 of The Anatomy Lesson,” he urged Updike in 1984. “My answer to the last paragraph of your review.”

Somehow, despite their mutual respect and occasional get-togethers, the friendship never deepened. Roth’s half of the correspondence is warm and funny (another difference: Roth was far funnier), his fondness tinged with envy. “Reading you when I’m at work discourages me terribly—that fucking fluency!” Roth wrote Updike in 1978. That wasn’t the only source of envy. “He knows so much, about golf, about porn, about kids, about America,” Roth told David Plante. “I don’t know anything about anything.” Indeed, one picks up on a subtle antagonism to Roth’s joshing. “Poor Rabbit. Must he die just because you’re tired?” he needled Updike in 1990. More than once, Roth bristled at Updike’s criticism. He couldn’t understand Jewish novels; he had no comprehension of Jewish history or the Jewish psyche. “We are in history up to our knees,” he told an interviewer, dismissing Updike’s review of The Anatomy Lesson.

To some degree, both men were guarded and self-protective. Updike’s shield was amiability; Roth’s was humor and flattery. Of the two, Roth seemed more eager to pursue a deeper friendship. Roth professed “affectionate sympathy and something even more than that” to Updike in 1991, yet sensed a certain resistance, a studied aloofness, on Updike’s part. Any chance for friendship was ruined by Updike’s incisive criticism of Roth’s novels. Reviewing The Anatomy Lesson, Updike complained of “the grinding, whining paragraphs” and suggested that “by the age of fifty a writer should have settled his old scores.” That rankled. In 1993, Updike delivered several sharp blows to Roth’s ego in the process of criticizing Operation Shylock (final verdict: Roth was “an exhausting author to be with”). The final blow came in 1999, when Updike, writing in The New York Review of Books, endorsed Claire Bloom’s vindictive memoir of her relationship with Roth. That did it: Roth was furious; the men never spoke again. Late in life, his wounds somewhat healed, Roth would claim to regret their estrangement. “I think you are next after Gordimer,” he wrote Updike in October 1991. Of course, neither would follow Gordimer, which proved another lasting connection between the men—America’s greatest nonwinners of the Nobel Prize.

From Harvard, I took a quick (self-funded) trip down I-395, to Yale, where Janet Malcolm’s papers had been deposited without much fanfare in 2012. That they’re available at all is a bit surprising: Malcolm, famously private, wrote frequently about the moral hazards of journalism and biography. Her papers are a feast for researchers, including, as they do, letters to and from J.D. Salinger; recordings of Malcolm interviewing profile subjects; and Malcolm’s manuscripts, with Roth’s comments scribbled in the margins. I arrived on March 11, just as Yale restricted library access over fears of the coronavirus. An archivist gave the standard spiel, with an epidemiological twist: No pens, no jackets, no close contact with other researchers.

Soon, downstairs, in the still atmosphere of the reading room, the Malcolm collection began to materialize: six gunmetal gray boxes containing drafts, notebooks, and audiocassettes, along with Roth’s letters to Malcolm. Earlier that week, I had been reviewing a different set of Roth letters and marveling at Roth’s single-mindedness. A substantial portion of Roth’s letters from 1956-2007 are concerned with literature—opinions, interpretations, recommendations. A dozen interesting syllabi could be assembled from Roth’s recommendations; his tastes roamed from Kafka to Updike to his European contemporaries. “Do you know Danilo Kiš, a Yugoslov writer?” he wrote Atlas, recommending A Tomb for Boris Davidovich. For 15 years, Roth curated Penguin’s “Writers from the Other Europe” series, resurrecting lost classics and anointing foreign authors. It’s possible that no one besides Susan Sontag was a louder champion for underappreciated European writers.

Roth could be an astringent critic, especially of dull writing (“What an earnest and deadly flogging of a dead latka,” he told a friend after slogging through an essay on “the death of the Jewish novel”). He could be almost as blunt when reviewing friends’ manuscripts, as the Malcolm papers reveal. “I gave you the kind of reading I give myself,” Roth told Malcolm after taking a scythe to her draft of The Silent Woman. The manuscript, littered with blunt, incisive notes—“weak”; “pretentious”; “you’re protecting yourself”—shows the full force of Roth’s intelligence brought to bear on the project of editing. “Janet! Have you lost your mind?” Roth scribbled in thick blue marker next to a passage about J.D. Salinger and copyright law. Below that, in screaming caps, is a plea to “THINK THIS THROUGH” before publishing (Malcolm ignored him; the passage remained).

In a more general (and gentler) vein, Roth prodded Malcolm to let loose, to not constrain herself. “There is a devil in you called Jana and she should be encouraged, prodded, rewarded at every turn.” Some variety of this advice went out to many writers, especially young, inhibited writers. Roth had come to see his own early writing “as having to do with that attempt to be fully sublimated, or civilized,” he told Solotaroff. Now he sang the virtues of being uncivilized. “The more playful, the more astute—law of kindergarten, law of life,” he told Malcolm. No less an eminence than Saul Bellow received the same advice: “it might have benefited from being written more freely and openly,” Roth wrote Bellow regarding his novella The Actual.

Something of a life-philosophy emerges from Roth’s letters. Roth can sound like Nietzsche, exhorting friends to “live dangerously,” or like Henry James (“Live all you can”). “To hell with a peaceful life. Seize the day,” Roth told Atlas, pushing him to attempt a biography of Saul Bellow. (Roth would regret it: He couldn’t stand “the atrocious Atlas book,” he later wrote.) A second Rothian principle was ignoring criticism, being utterly impervious. “Write what you want the way you want,” he ordered Atlas, and let the chips fall where they may (“which may be on your head,” he added, “but so what again?”). Caring too much was foolish and inhibiting. “Fuck ‘em,” he told Atlas more than once.

Surely Roth was speaking to himself, too. A bad review, Kingsley Amis said, should spoil your breakfast, but not your lunch. Roth had no such rule, nor any patience with reviewers. “It’s fucking hopeless, even when they like you,” he wrote David Rieff after The Anatomy Lesson was blandly praised (“I can’t read another idiotic word about the book”). Roth’s crusade to stop caring—perhaps the great struggle of his writing life, besides writing itself—lasted decades. Ignore the critics, he told friends. Be aloof. Salvation lies in not caring. Yet Roth’s tendency was to fixate, to relive the past. “What must it be like to let things go?” he asked Malcolm. He could strive for indifference, he told Solotaroff, “But publication turns me into a cocker spaniel, too easily pleased and too easily hurt.”

Moments of tenderness in Roth are like acts of kindness on the New York subway: rare, and most surprising for being rare. The great revelation of Roth’s letters is what a generous, sympathetic, solicitous friend he was. Whether that was innate to him or something he cultivated over time is hard to say, but he seems to have found greater reserves of empathy and generosity after the searing experience of Portnoy’s Complaint.

Roth’s greatest sympathy went to friends in trouble: depressed, embattled, or simply stuck. “You’re taking the Atlas shit like a champ,” he wrote Saul Bellow after Atlas’ rancorous biography was published. “You’re in the clear.” To Janet Malcolm, besieged by a libel lawsuit, he was a stalwart. “You will be vindicated in court, it’ll be grueling and punishing along the way, but you will be vindicated,” he wrote her in 1991. With young male writers, Roth was comfortable in the alpha role, offering support and wisdom. He surely saw parts of himself in the hypersensitive Atlas, eyeing his reputation, worrying over criticism. “Life is up and down. You suffer again, and you’ll be happy,” he told Atlas, forlorn after leaving The New York Times.

In a way, Roth’s darker side—his anger, self-loathing, and narcissism—went into his novels, while the best of him—his sympathy and solicitude—went into his correspondence. “Philip Roth has in fact everything but one thing: a generous spirit,” the critic Joseph Epstein once wrote. One can certainly get that impression from Roth’s novels, but his letters belie the accusation. Roth relished opportunities to be helpful and generous. He just didn’t channel that generosity, that largeness of spirit, into his fiction, and it was never part of his sober and intimidating public persona.

In the Roth archives, I thought frequently about biography. Roth was highly conflicted about biographers; he often lumped them in with journalists, those shameless snoops, and their sources, those babbling yentas. “Sore point,” he conceded to Atlas, the literary journalist. It wasn’t just “the sticky gossip” of journalistic profiles that offended Roth; it was “seeing it taken seriously, simply because it happens in the context of such intelligent writing about books.” So a writer had affairs and personal meshugas. Who cared? Literature was what mattered—the writing, not the writer.

High-minded though that sounds, Roth wasn’t a purist; like all readers, he enjoyed voyeuristic glances into writers’ private lives. “When you admire a writer you become curious. You look for his secret,” he wrote in The Ghost Writer, capturing neatly the allure of biography. As for having his own “sticky stuff” exposed, that was another matter entirely. Why would Roth, so desperate to keep his private life private, ever appoint a biographer? After firing his friend Ross Miller, he selected Blake Bailey, turning over reams of material, including private correspondence. Did vanity cloud Roth’s judgment? Was he desperate to keep producing books after he stopped writing them? Or was he attempting to safeguard his reputation? “He was not looking for a Boswell to fix him to the page,” Taylor writes in his memoir, “but for a ventriloquist’s dummy to sit in his lap.”

Roth had his own advice for biographers. In both The Counterlife and Deception, he warns against the simplifying, sanitizing, legendizing impulse. Writers are capricious; their nature is “impurity”; their vices are “fixation, isolation, venom, fetishism, austerity, levity, perplexity, childishness, et cetera.” A ruthless biographer could confront those “impurities,” but there remains the problem of interpretation. In the gospel according to Roth, we’re all brilliant misinterpreters of each other: We project; we idealize; we overlook; we misconstrue. Getting people wrong is second nature. Life is about “getting them wrong and wrong and wrong,” he once wrote, “and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again.”

Roth’s fatalism could serve as a warning—or a challenge—to future Roth scholars. “Think you can figure me out?” Roth seems to be saying. “Forget it.” After reading Roth’s letters, I would agree: Roth is a minefield for biographers. His memory was phenomenal, but he also remembered plenty of things that didn’t happen. Roth lied for the usual reasons—to make himself more interesting; to preserve a benign self-image; to conceal shameful and humiliating secrets. The lesson for biographers: You can’t be skeptical enough. Nothing in Roth’s memoirs or interviews should be taken at face value.

Beyond that is the problem of Roth’s multiple selves. Readers prefer coherent subjects, but Roth simply wasn’t coherent. To a biographer, it may make sense to think of Roth not as a single person, but a handful of people: The generous, solicitous friend. The rage-filled novelist who thrived on antagonisms. The charmingly exuberant performer. The avid, life-devouring Roth. The abstemious, solitary Roth. And, not least, the self-absorbed narcissist, who, of all the Roths, may be hardest to stomach. “The man gives nothing. (Yes, except to literature),” Janet Malcolm concluded. “He is completely selfish and manipulative. How taken in I was.”

Reading Roth’s letters unquestionably brings you closer to Roth, and if the view isn’t always pretty, a hard, honest glance is still salutary. Someday, perhaps, some enterprising editor will collect those letters, hundreds, perhaps thousands of them, and assemble a Selected Letters. It would be a wonderful challenge. Roth is scattered, archivally speaking, around the country, but the collections are easy to locate, and a legion of helpful archivists stand ready to guide curious researchers.

So here’s to the final volume of Roth’s Library of America series: Roth’s correspondence. In a sense, it will keep Roth alive, preserving the brilliant, prickly, secretive, charming, generous, cruel, exuberant, paranoid, manipulative character that was Philip Roth. It will spare him a gentle embalming by posterity.

Jesse Tisch is a writer, editor, and researcher. He lives in New York City.