The Ontology of Pop Physics

A slew of popularizing science books delve into the basic mismatch between being and human being

The World According to Physics, by the British physicist Jim Al-Khalili, looks less like a book that belongs in the science section of Barnes & Noble than one you might find in a hotel nightstand. There is no dustjacket, just the handsome blue cloth covers embossed with silver lettering, like a Bible. The title is self-consciously New Testament, following the formula of the Gospels according to Mark, Luke, Matthew, and John. And on the back cover, in lieu of the usual blurbs from fellow science writers, there are phrases of the kind that adorn proselytizers’ pamphlets: “The Knowledge We Have Revealed,” “The True Nature of Reality, Illuminated.”

These design choices help to surface a tension found in most popular books about physics and cosmology—a genre I started to read avidly a couple of years ago. Though they are explicitly anti-religious, such books function as religious texts. We turn to them in the same way that people once turned to collections of sermons or scriptural exegeses, in search of the fundamental truths that structure our world. Those truths used to be derived from divine revelation—Moses’, Jesus’ or Muhammad’s; for educated people today, regardless of our formal religious affiliation, they mainly derive from science. And like our ancestors, we are in need of experts who can mediate between the complexity of truth and our own limited capacities—even if a great deal gets lost in the process.

The modern genre of pop cosmology began with the big bang of Stephen Hawking’s 1988 megabestseller, A Brief History of Time. Since then, world-class physicists like Michio Kaku, Steven Weinberg, and Freeman Dyson, who died earlier this year at the age of 96, have earned wider fame by writing popular accounts of fundamental physical concepts: time and space, matter and energy, the origin and destiny of the universe. In Brian Greene’s new contribution to the genre, Until the End of Time, the table of contents alone could blow your mind, with chapter headings like “Origins and Entropy,” “Particles and Consciousness,” “Duration and Impermanence.”

These subjects are now a part of physics, but they used to belong to metaphysics. That term was coined in the first century CE by an anonymous editor of the works of Aristotle, who used it to refer to a treatise that students should learn after studying his Physics—in Greek, ta meta ta physica literally means “after the Physics.” Aristotle referred to the subject as “first philosophy,” because it dealt with the most primary of all subjects: being itself, what he calls “being as being.” What does it mean to say that something is? How do things come to be and how do they change? Is the cosmos eternal or does it have a beginning and an end?

Other intellectual disciplines deal with pragmatic questions: Political philosophy is about how to govern, ethics is about how to live. But metaphysics, Aristotle says, is the highest form of thought because it has no aim other than pure knowledge. “We do not seek it for the sake of any other advantage; but as the man is free, we say, who exists for his own sake and not for another’s, so we pursue this as the only free science, for it alone exists for its own sake.”

Aristotle lived in the 4th century BCE, and his metaphysical teachings dominated Western thought for the next 2,000 years. They were so convincing that Jewish, Christian, and Muslim thinkers all looked for ways to reconcile their holy books with Greek metaphysics. The classic Jewish example is Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed, written in 1190, which comes very close to saying that the world has always existed—as Aristotle teaches, and Genesis most definitely does not.

If we could clone Maimonides today, it’s likely that he would grow up to be a physicist rather than a rabbi. That’s because questions about metaphysics (though not necessarily about politics or ethics) now receive better answers from science than they ever did from religion or philosophy. Starting in Europe in the 17th century, the scientific revolution rejected the Aristotelian idea that there is a sharp divide between physical knowledge, which is practical and empirical, and metaphysical knowledge, which is ideal and speculative.

Thanks to the scientific method, the modern world was able to actually resolve debates that in the ancient world simply went around and around. As Al-Khalili says, “through rational analysis and careful observation, we can now claim with a high degree of confidence that we know quite a lot about our universe.” We now know that matter is made of atoms, as Democritus guessed but couldn’t prove, and we even know what the atoms are made of. We know that the stars obey the same laws of motion as objects on earth, as Galileo and Newton showed, and aren’t made of a unique element, as Aristotle believed.

What does it mean to say that something is? How do things come to be and how do they change? Is the cosmos eternal or does it have a beginning and an end?

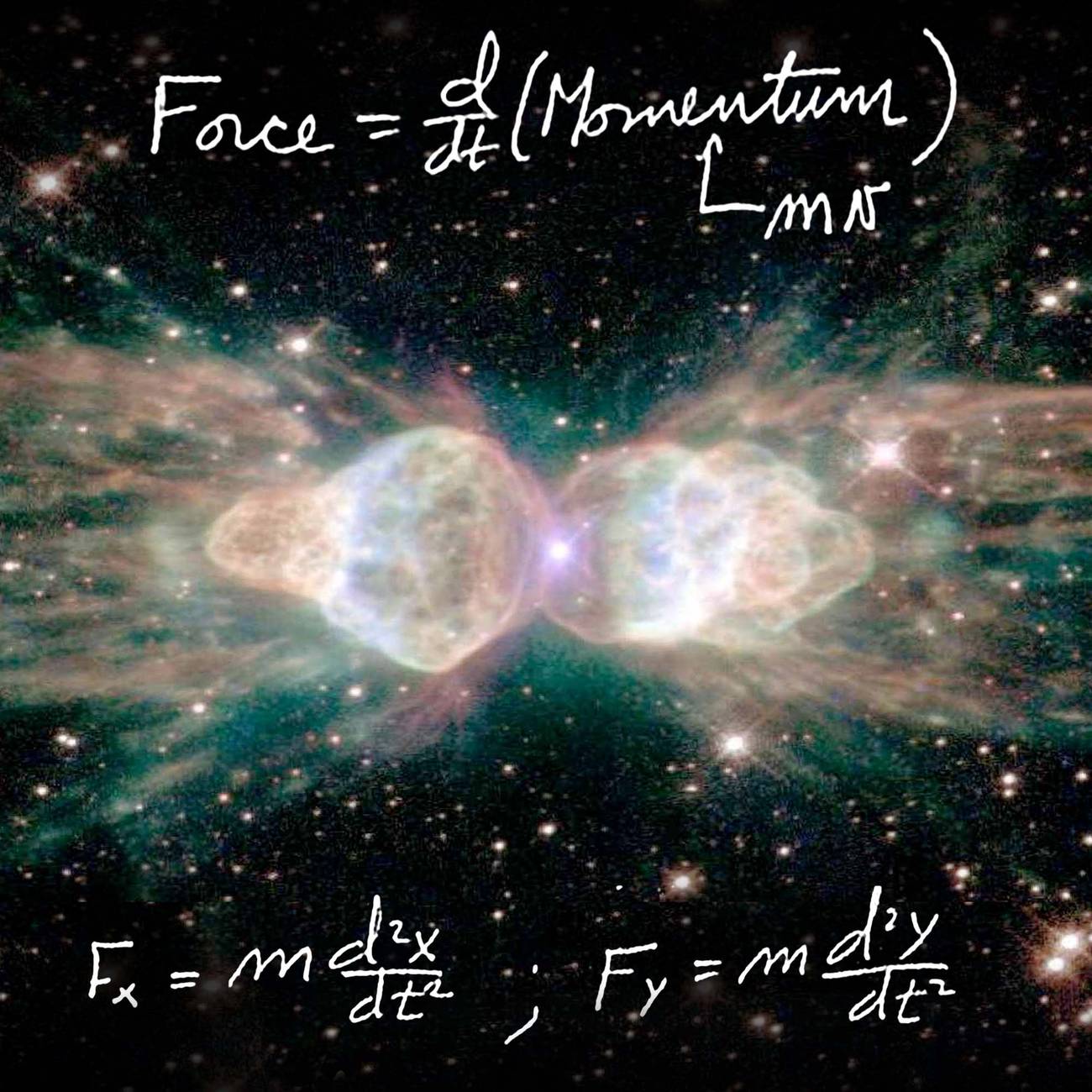

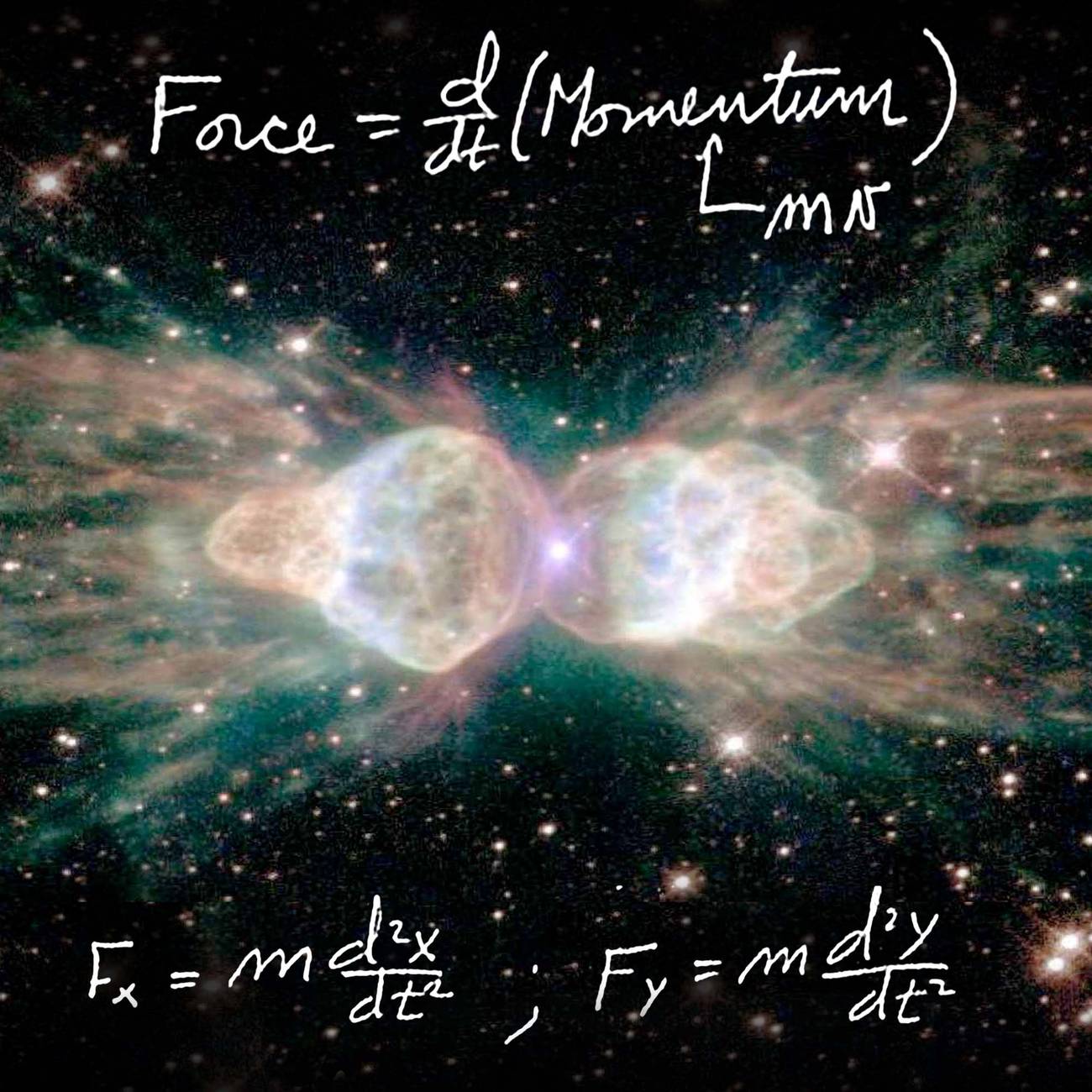

But when Al-Khalili says that “we know quite a lot about our universe,” the pronoun is equivocal. He knows quite a lot, because he has a deep mathematical understanding of the topics he discusses—thermodynamics, relativity, string theory. But the reader of The World According to Physics and similar books doesn’t actually come to know these things, because they are not susceptible of being taught in this format; they can only be loosely paraphrased. A real introduction to physics—like the famous lectures delivered by Richard Feynman at Cal Tech in 1963, which became a standard textbook—is all equations. As Galileo said 400 years ago, the book of nature is written in the language of mathematics. (Look, for example, at this page from Feynman—and that’s from early in the course, the eighth of 115 lectures.)

An introduction to physics that contains no equations is like an introduction to French that contains no French words, but tries instead to capture the essence of the language by discussing it in English. Of course, popular writers on physics must abide by that constraint because they are writing for mathematical illiterates, like me, who wouldn’t be able to understand the equations. (Sometimes I browse math articles in Wikipedia simply to immerse myself in their majestic incomprehensibility, like visiting a foreign planet.)

Such books don’t teach physical truths; what they teach is that physical truth is knowable in principle, because physicists know it. Ironically, this means that a layperson in science is in basically the same position as a layperson in religion. The Kuzari, Yehuda Halevi’s 12th-century work of Jewish apologetics, uses a similar argument to justify belief in miracles. When we read in the Torah that manna rained from heaven to feed the Israelites in the desert, for instance, our natural reaction is to be skeptical. But Halevi writes that the miracle is “irrefutable,” because it “occurred to six hundred thousand people for forty years.” We ourselves have never seen manna from heaven, but other people say they did and we have to trust them. So, too, we ourselves could never understand Schrodinger’s equation describing the state of a quantum system, but we trust other people who say they do.

The great difference, of course, is that science proves the truth of its account of the world by its ability to change the world, which religion cannot do. In the Talmud, for instance, the sages lay down rules for how to end a drought by fasting. First, community leaders undertake a daytime fast three days a week; if that doesn’t work, the whole community joins in; if there’s still no rain, everyone must fast for seven days and go into mourning. These are attempts to convince God to change the weather by demonstrating the desperate need of the Jewish people. But the Talmud’s procedure tacitly admits its own uselessness: Fasting doesn’t change the weather, which is why you have to keep doing it until the weather changes.

Modern science also can’t conjure rain out of a clear sky. As Al-Khalili explains, weather remains one of the most difficult subjects for physicists because of “the sheer complexity of what we are trying to model and the number of variables we would need to know very precisely—from temperature to variations in the atmosphere and the oceans to air pressure, wind direction and speed, solar activity, and so on.” But he emphasizes that “this does not mean that such knowledge couldn’t in principle be known.” Even if we don’t know all the causes of weather patterns, we know what doesn’t cause them—for instance, the anger of an offended deity.

This is an example of the kind of sacrifice that science asks us to make when it comes to metaphysics. Traditional metaphysics understood the world in categories drawn from human experience. For religion, that meant the world is governed by a God who shares the same kinds of motivations we do—who inflicts droughts out of anger and can be appeased by submission. For philosophy, it meant the world has the same kinds of instincts we do about what is natural and fitting. Aristotle believed that a stone falls to the ground because it naturally wants to be reunited with the element of earth, while flame rises because it naturally wants to rejoin the element of air.

The price of admission to modern science is recognizing that we can’t understand the world just by thinking about it, because our ways of thinking are suited to understanding human being, not “being as being.” Instead, we have to humble ourselves before being—to pay close attention to what it actually does, not what we think makes sense for it to do.

Nothing demonstrates this more clearly than quantum physics, which in the early 20th century forced physicists to discard their basic intuitions about how the world works. Through Two Doors at Once, a 2018 book by Anil Ananthaswamy, illustrates the strangeness of quantum physics by focusing on the famous “double-slit experiment,” which involves shining a beam of light at a metal pierced by two parallel slits, behind which stands a screen that registers where the light strikes it.

As the English physicist Thomas Young showed in 1803, the pattern that builds up on the screen is a band of light and dark regions, proving his theory that light is a wave. As the wave of the light beam passes through the slits, it splits into two waves that interfere with each other, creating light patches on the screen where their crests add together and dark patches where a crest and a trough cancel each other out. The same phenomenon can be seen in waves on the surface of water.

In the 20th century, however, Einstein found that in order to explain how light interacts with electrons, light can only exist in discrete amounts, or quanta (the origin of the phrase “quantum physics”). These particles of light came to be called photons, and with more advanced scientific equipment it became possible to perform the double-slit experiment by firing just one photon at a time at the plate. This causes individual points to appear on the screen behind it—just as you would expect if light is not a wave but a particle.

But if you continue to send one photon at a time through the slits, something uncanny happens: As the individual points accumulate, they build up a band of light and dark regions, just as when waves of light pass through the slits. The only way to explain this is to say that light is both a wave and a particle—which means that, at the most fundamental level, nature violates what Aristotle called in the Metaphysics “the most indisputable of all beliefs … that contradictory statements are not at the same time true.”

Feynman said that the double-slit experiment induces a “perpetual torment that results from your saying to yourself, ‘But how can it be like that?’” The word “torment” is strong but apt, because in defying our intuitions about space, time and logic, modern physics shows that there is a basic mismatch between being and human being. Physics revokes the metaphysical promise of the Bible, which says that the world was created for man to rule it, and also the promise of philosophy, which believed since Protagoras that “man is the measure of all things.”

Popular physics writing is best understood as therapy for this torment—as metaphysical self-help. In Until the End of Time, Brian Greene makes this aim more explicit than most such writers. “We are ephemeral. We are evanescent,” he acknowledges in the book’s last chapter, “The Nobility of Being” (not a subject Feynman has much to say about in his CalTech lectures). But Greene moves quickly into affirmation: “How utterly wondrous it is that a small collection of the universe’s particles can rise up, examine themselves and the reality they inhabit, determine just how transitory they are, and with a flitting burst of activity create beauty, establish connection, and illuminate mystery.” It’s the same soothing tone a doctor uses to calm a child who’s about to get a shot.

By writing about concepts like quantum entanglement and cosmic background radiation, physicists are trying to help us acclimate to a modern metaphysical reality that remains permanently new and challenging, even though its essence has been clear for centuries. That’s because we are all born with an instinct to find human meanings in the universe. The scientific revolution isn’t a historical event that happened a few centuries ago, but a process that takes place in the life of every person who learns scientific truth.

The final irony, however, is that this piety toward the truth is itself a legacy of the old, religious metaphysics that science rejects. For why would we be so intent on living in the truth, even at the cost of our own happiness, unless truth is a commandment, a mitzvah? In the end, Nietzsche wrote in The Gay Science, “it is always a metaphysical faith on which our faith in science rests—that even we seekers after knowledge today, we godless anti-metaphysicians, still take our fire from the flame lit by a faith a millennium old … that God is truth, that the truth is divine.”

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.