The Flagellants of the Western World

Like God, colonialism is invisible and omnipresent, responsible for everything that happens on Earth

What are we to make of the fact that the trial of colonialism has been reopened 60 years after the wave of independence? It’s not as if colonialism has been ignored or suppressed in the schools; indeed, it’s taught in all the textbooks, where, unfortunately, it’s also a beacon for all those who long for the old divisions. Just as there are some who can’t get over the passing of the Cold War, there are intellectuals who have never mentally accepted the independence of territories formerly under French, English, or Dutch control. For a big slice of the left at a loss to understand the world, anti-colonialism serves as a substitute Marxism, and also as something worse.

Anyone can, if so inclined, inhabit the virtual land of slavery and colonialism as hazy concepts, temporary habitats occupied for the purpose of expressing one’s anger or indignation. Invoking colonialism allows one to reinsert oneself into a glorious tradition, though at the cost of epic distortions. Generations of militants, inconsolable at the passing of the old fights, have reclaimed the vocabulary of liberation and are reciting a catechism written by others, as if nothing had happened in the meantime. These heroes are reminiscent of those Japanese soldiers stranded on Pacific islands who still hadn’t heard, at the end of the 20th century, that World War II had ended. Choosing to play the hero, even after the fighting is over, gives you the sad glamour of a lone sniper—without exposing you to the slightest risk.

The West has all of the qualifications for an ideal guilty party, of course. In the New World, it founded a nation on exterminating Indians, enslaving Africans, and segregating races. Back in Europe, it carries the weight of four centuries of colonialism, imperialism, and slavery, even allowing for the fact that European nations led in urging its abolition. But what makes the Western world the scapegoat par excellence is that it acknowledges its crimes, through the voices of its most eloquent consciences, from Bartholomé de Las Casas to André Gide and Aimé Césaire—and passing through Montaigne, Voltaire, and Clémenceau. The West invented the uneasy conscience, making a daily practice of repentance with an almost mechanical plasticity. And this distinguishes it from other empires that struggle to recognize their evil deeds, such as the Russian and Ottoman empires, the Chinese dynasties, and the successors to various Arab kingdoms that occupied Spain for almost seven centuries. Only we Westerners beat our breasts, while many other cultures present themselves as victims or as unknowing innocents.

The Jesuit Louis Bourdaloue, the renowned clergyman in the court of Louis XIV, followed St. Bernard in distinguishing four types of consciences: clear and serene (paradise), clear but troubled (purgatory), guilty and troubled (hell), and guilty but serene (despair). How can we avoid remarking that a substantial segment of the left falls into this last category? In fact, we have rarely seen an elite embrace with such enthusiasm culpability as a cause, to the point of endorsing the flaws of others and crying out, “I’ve got remorse to offer; who has a crime?

The guilty conscience suits us: It’s the alibi for our abdication. It expresses the surprisingly easy coexistence of dread and calm, of denial and good digestion. We wrap ourselves in the robes of the perpetual criminal, the better to keep our distance from the world and its torments. And now the West is weaker than ever—rudderless, leaderless—since the United States withdrew from world affairs.

Significantly, the West has been stigmatized as its role has declined, a phenomenon that diplomats in Munich in February 2020 termed “Westlessness,” or the disappearance of the Western bloc. And now it’s time to give the Western world what it has long deserved. Or so the thinking goes. So the trial of Europe goes on, with Europe itself beating the drum—and America following closely behind, having begun its own odyssey of repentance.

Proud to beat its breast ostentatiously, the Old World assumes the universal and apostolic monopoly on barbarism. Its aim is no longer world conquest but to break with history, which nevertheless persists in showing its head on the continent in the form of Islamist attacks directed from the Middle East, the crisis of migrants flocking to its gates, and the aggressiveness of the neo-sultan Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who is openly threatening Greece, Cyprus, and France, and is recolonizing Libya, which was only yesterday a possession of the Sublime Porte.

But we athletes of contrition believe that we deserve whatever happens to us: The duty of penance is without end and will cease only once the accursed West has been wiped away like a stain from a stainless surface. And yet we have known since Freud that masochism is just inverted sadism, a desire to dominate that is turned against the self.

Europe remains messianic in a masochistic key, militant about its own weakness, an exporter of humility and wisdom. Its apparent scorn for itself is a thin disguise for a major infatuation. The only savagery it acknowledges is its own; it’s a point of pride which Europe denies to others by explaining away their evil actions as products of extenuating circumstances. It sports its malfeasance the way others wear their ribbons and medals.

The so-called decolonial movement aims, among other things, to drive a stake into the heart of the Northern Hemisphere and to bring down its fortresses. The hemisphere deserves to be colonized by those formerly colonized, vanquished by those whom it had defeated. Before the colonial invasions, the story goes, Africa was an Eden that was then spoiled. Although that myth has been debunked by every historian, the presumed destruction must still be paid for. The period of penance is no longer enough: Now what we need to do is to blow up Europe (and then the United States) from the inside—and enlightened Europeans must lend a hand.

One example: The far-left Podemos party demanded in 2016 that Spain apologize to Islam for having retaken Andalusia in the Reconquista and expelling the Muslims. One might have thought the reverse: that northern Africa should extend its solemn apologies to Spain for having occupied it for seven centuries. But no! The liberation struggle went on for several centuries and was Europe’s first anti-colonial war. And it was a fierce one, particularly with the arrival, in 1478, of the Spanish Inquisition against Muslims and Jews, which transformed Catholicism into an ideology of conquest. But in the course of labeling the Reconquista as “fascist and genocidal,” we might have been reminded of the wars of independence of the 1960s, many of which also featured bloodbaths and the expulsion of Jews (to take one example) from the entire Arab world. The myth of idyllic Andalusia is one that cannot stand up to facts or analysis and cries out for a more nuanced treatment.

A distinction must be made between colonialism, which for us moderns is wrong in principle, like fascism and communism, and colonization, which was diverse and complex, both harmful and beneficent, the story of which emerges from the painstaking work of historians who respect facts and nuances. Colonization did not in all cases prevent the establishment of ties or the maintenance of relations of mutual esteem and friendship a half-century after independence. “Colonialism,” by contrast, is a bit like the draft effect of a cloud after a storm: It never ends; like God, it is invisible but omnipresent.

Many intellectuals born in sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, and the Middle East and now living in France or the United Kingdom endlessly accuse Westerners of racism and neocolonialism. The paradox of these thinkers is as follows, it seems to me: By putting Europe in the dock, they are restoring it to the center. First, they are forgetting that of the 27 countries of the European Union, only eight were colonizers, less than a third, whereas the rest were colonized—by Arabs, the Russian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the USSR—and kept in servitude, some until the end of the 19th century, others until 1989. By seeking to marginalize Europe, or more precisely to “provincialize” it (Dipesh Chakrabarty), we keep it as the absolute point of reference. With the result that 60 years after eight countries of Western Europe ceased all colonization, they are as blameworthy as ever.

If Europe is detestable for so many reasons, as doubtless it is, if it combines racism, oppression, and beastliness, why pull out all the stops to come live here? Why do so many brilliant minds seek to teach and publish here? Those minds are driven by the determination to be recognized in the countries whose politics and policies they denounce so vehemently. The philosophers, writers, and celebrated novelists among them are rewarded, invited to speak, and awarded various prizes, yet they persist in vituperation. That strategy might be called seduction by insult: Let me in, so that I may curse you.

It’s a comfortable position, the pleasure of manipulating “white” guilt. And some Europeans delight in being ridiculed this way. Anglo-Ghanaian writer Kwame Anthony Appiah ironically summed up the situation as follows: “Postcoloniality is the condition of what we might ungenerously call a comprador intelligentsia: a relatively small group of western-style and western-trained writers and thinkers who trade in cultural products of world capitalism at the periphery.”

The status of “victim” intellectual exploring the recesses of the Western guilty conscience can be an excellent niche. The relationship of the two roles is invariable: the inquisitor who attacks, and the accused who self-flagellates.

These injections of shame are based on a postulate: Europe (and now the United States) has an inexpungable debt to the rest of the world. No amount of financial damages can compensate for the world’s incalculable loss. So goes the thinking of the “decolonial” intellectuals who have appointed themselves as the moral tax collectors of the planet—and who collect dividends from their compassion. In their eyes, Europe was made possible by the Third World (as we said in the 1960s), and its wealth rightfully belongs to its former colonies. That proposition is eminently contestable—colonialism may have cost the European countries more than it brought in and neither pillage nor theft have ever made for a solid economy, as Spain in its golden age, overwhelmed with its gold fever, attests.

To all of the thinkers who come to the West to find academic legitimacy, one is tempted to say, “Forget about us! Focus instead on building or rebuilding your countries.” The Franco-Senegalese novelist Fatou Diome put it well, while daring to break the taboo: “The refrain about colonization and slavery has become a business.”

Isn’t it surprising that the first nations to have abolished slavery (after having profited amply from it) are also the only ones facing accusations and demands for reparation? In other words, charged with the crime are only the countries that admitted to it—Europe and the United States (where a million lives were lost in the cause of abolition during the Civil War)—and declared the commerce in human beings to be barbaric?

To put it yet another way, while the West hardly invented slavery, it did invent abolition. Note that the slave trade was declared illegal in Yemen and Saudi Arabia as late as 1962 and in Mauritania only in 1980 (where it persists underground). Yet to point out that there were three waves of slavery—the Middle Eastern, which began as early as the seventh century and affected some 17 million captives, which Senegalese historian Tidiane N’dyaye has called a “veiled genocide”; the African, which combined domestic use of slaves with export networks (14 million people); and the Atlantic, which, in a shorter span of time, saw the deportation of nearly 11 million men, women, and children—is still taboo. Any historian who makes that observation runs the risk of being put on trial for revisionism. Meanwhile, we are still waiting for the Arab-Muslim world and a number of African countries to present their first public mea culpa for having hunted Black skins or to reflect on their own racism.

Our expansive consciences, so quick to honor the memory of those shipped off and tortured in centuries past, are strangely mute on the subject of the 40 million to 50 million people subjugated today in China, India, Pakistan, Africa, and the Middle East. It is strange that they should have been so unbothered when, in 2014, ISIS subjected thousands of Yazidis, Christians, and Shi’ites in Iraq to sexual servitude, or when the Libyans reopened slave markets on the outskirts of Tripoli in 2017. Slavery, the worst crime of which human beings are capable, is still among us; it is strange that those who care so deeply about slavery in the past care so little about those who are enslaved.

Postcolonialism is the Swiss army knife of explanations. It can be used to explain the bad situation of North Africans and Blacks in France, “owing to the persistence and the application of colonial approaches to certain categories of the population ... chiefly those originating from the former Empire.” Paris lays claim to the immigrant cities, exploits their wealth, and applies a violent, predatory policy. In the process, the French are turned into colonizers on their home ground who must be expropriated from metropolitan France. We read about the Minguettes south of Lyon or the slums on the north side of Marseille through the lens of the occupied territories; Paris’ La Courneuve is lumped together with the ghettos of Chicago.

We live in a sort of fantastical spatial-temporal telescoping, where eras and continents are superimposed and everything is mixed together. Whenever rioters confront the police, petitions are circulated to demand their withdrawal and to permit the self-administration of the affected area by gangs or radical Islamists. But the fact is that the situation in the immigrant suburbs of French cities involves “a counter-society in the midst of a profound cultural break” (Gilles Kepel), not the subordination for commercial ends that was the trademark of the colonial empires. The colonizers held a country, exploited it, but they did not abandon it to traffickers. Whence the importance of a democratic retaking of these areas, hinging on education, safe schools, and the return of public services, health care, fire brigades—in short, reintegration.

France is often faulted for its abstract concept of citizenship: By emphasizing likeness (or similarity) over difference, it is said to lose sight of all the men and women from other circumstances who are struggling to enter the magic circle of the alike, the similar. The charge is well-founded. And the task should be to understand why all of these people are mobilizing: in the name of what or whom? Is it because of a denied equality before the law that has left them at the threshold of the republic? Or an affront so extreme that it has placed them in a position of absolute exteriority?

To recite the endless list of killings, deportations, exploitations of which our forebears are alleged to be guilty is to enter a bottomless pit full of rancor and vengeance; it is to make today’s citizens pay for the crimes of their predecessors.

The decolonials don’t go this route. Instead of integrating its various minorities, they say, society should adapt itself to them and embrace their messianic vocation. Their past or present suffering supposedly creates for them unlimited accounts receivable. But that sort of thinking neglects the fact that France’s social elevator has been operating for decades, enabling so many citizens originating from Africa, South Asia, the Pacific, and the Caribbean to become lawyers, physicians, entrepreneurs, scholars, scientists, and politicians that their presence is taken for granted and no longer attracts much attention.

To label oneself, as some political groups do, victims of birth is to lay claim to special treatment, to grant themselves a moral free pass that entitles them to jump the queue of ordinary legal and political recourse. Even when one does evil, one remains innocent. But this is a double-edged sword. A feeling of belonging is not built on a dramatized wrong, real or imagined; it is built on a shared collective experience and expanded participation in public and professional life.

Professional victims (and their lobbies) do not make good citizens. No nation can ever be good enough for them if it urges the pardoning of past wrongs, the symbolic allegiance to a spiritual principle born from a distinctive history, and voluntary association with a national community, with all that that entails in the way of learning the language and participating in its culture.

To make history, one must begin by forgetting it, or at least leaving it to the historians in cases where memory, prone as it can be to resentment, divides and condemns. Memory can wake the dead, the tortured; it can thrust them in the face of the living and scream, “How can you keep a cool head? Demand an apology!”

But to recite the endless list of killings, deportations, exploitations of which our forebears are alleged to be guilty is to enter a bottomless pit full of rancor and vengeance; it is to make today’s citizens pay for the crimes of their predecessors. Digging up all the bodies means digging up all the hate, applying the principle of an eye for an eye across a distance of centuries. One example among hundreds: Should Catholics and Protestants continue to hurl abuse at one another, knives out, on the grounds that they killed each other with ferocity for three centuries in France? History consists as much of shared elisions as of shared memories; it includes abolition of the blood debts contracted between human societies.

I hate to harp on the obvious, but decolonization happened. Doubtless imperfectly and leaving countless traces, but, in the end, France, like Britain and Belgium, turned the page. Recent generations have no connection to this period, and their amnesia about it results from their detachment.

Old Europe certainly has blood on its hands and has acted ignominiously on many occasions, but it is one of the few continents to have thought through its barbarism and distanced itself from it. Present-day Turkey, by contrast, still refuses to acknowledge the genocides of the Armenians in 1915 and of the Assyrians from 1914 to 1923. No one is holding their breath while waiting for Moscow to ask forgiveness from the nations of Eastern Europe, which the USSR colonized and pillaged under the guise of friendship between peoples. Communist China does not publicize the mass murders of Mao Zedong, which claimed tens of millions of victims. Not to mention Sunni and Shi’ite Islam, which, unlike the Catholics of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), are nowhere near conducting their own examination of conscience.

History is no longer divided, if it ever was, between sinful nations and angelic continents, accursed races and sacrosanct peoples, but rather between democracies that confess their errors and dictatorships (theocratic or autocratic) that hide them, while cloaking themselves in the trappings of martyrdom. There are no innocent nations, there are only states that do not want to know the truth.

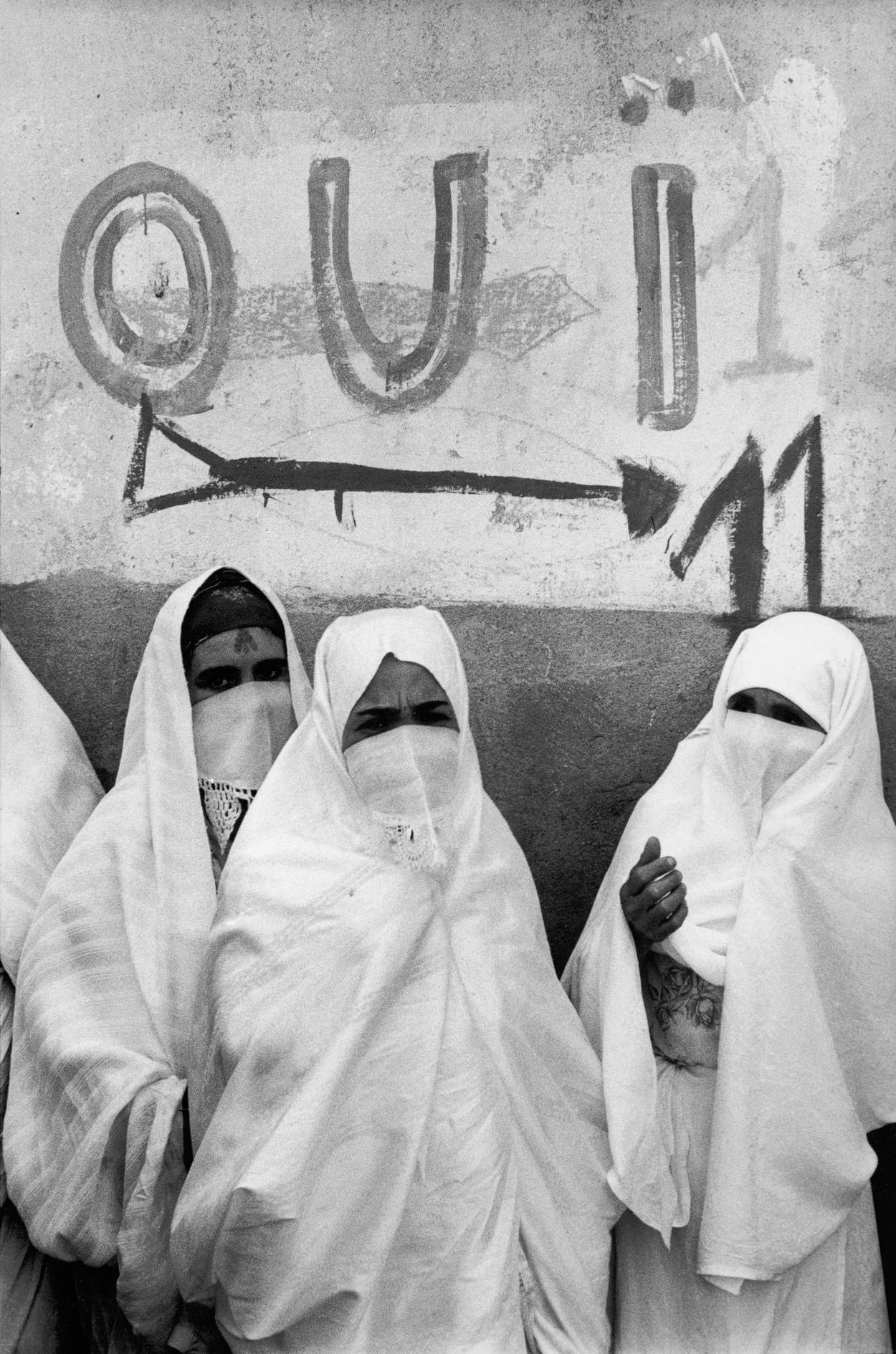

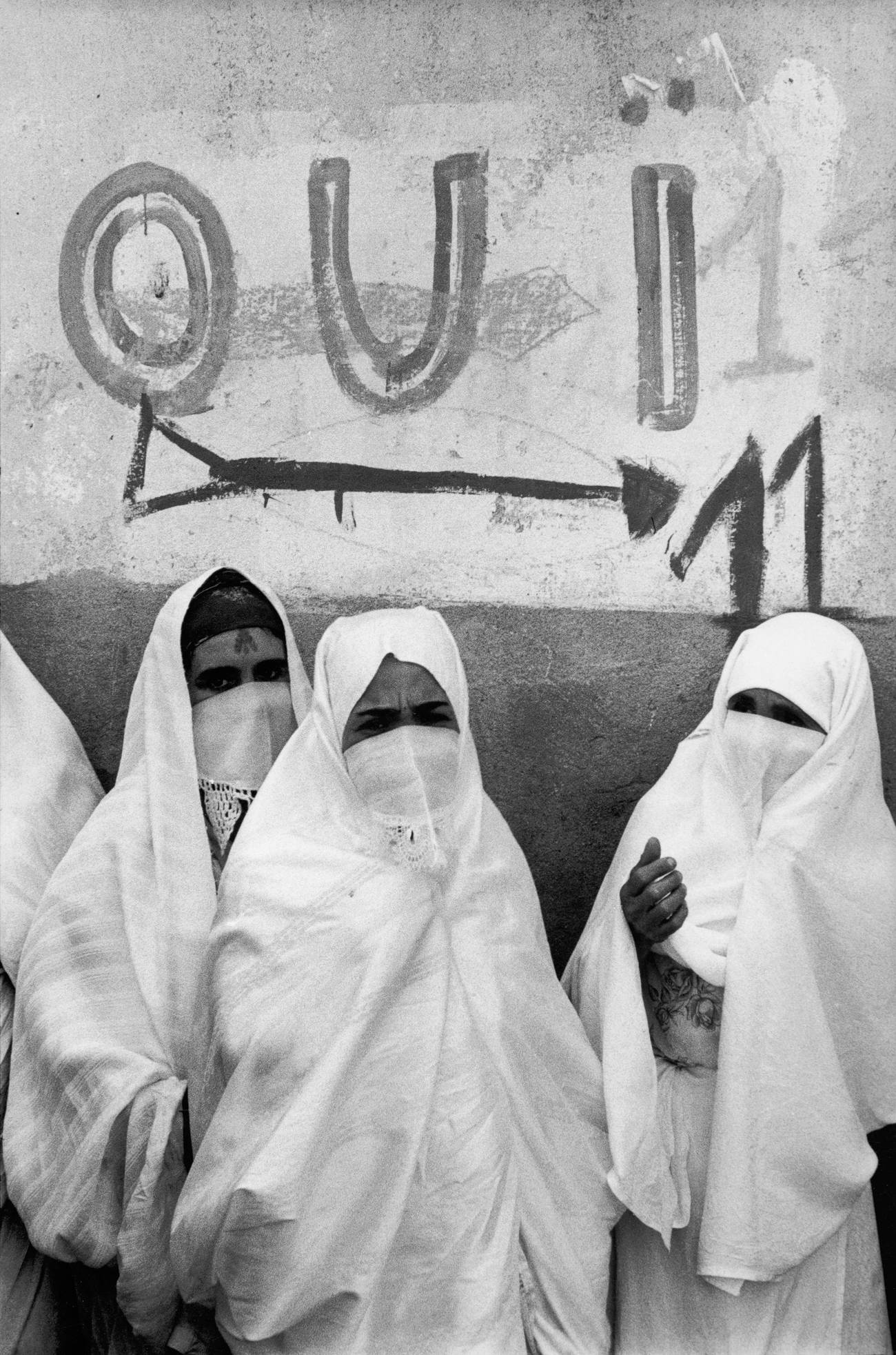

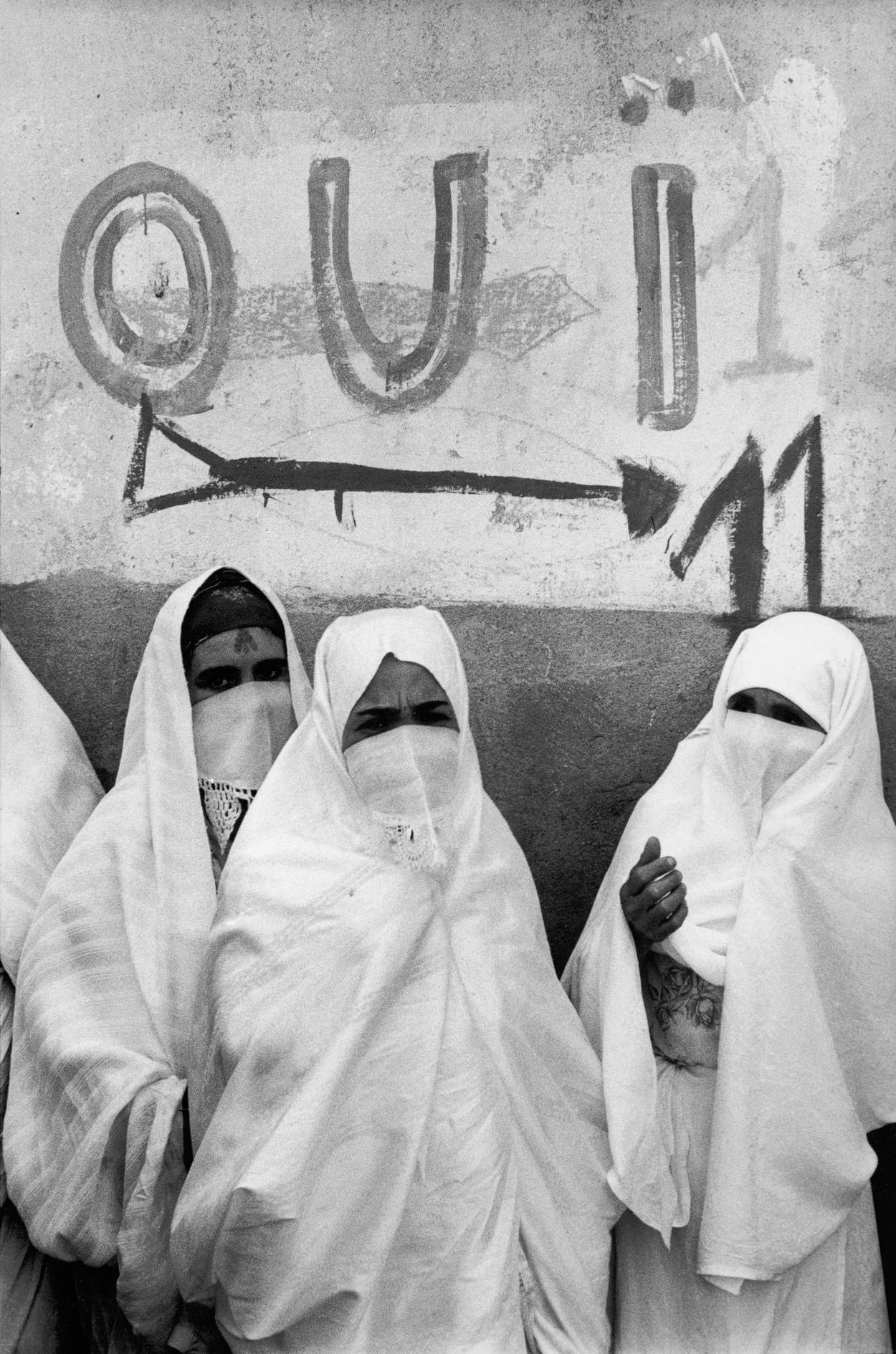

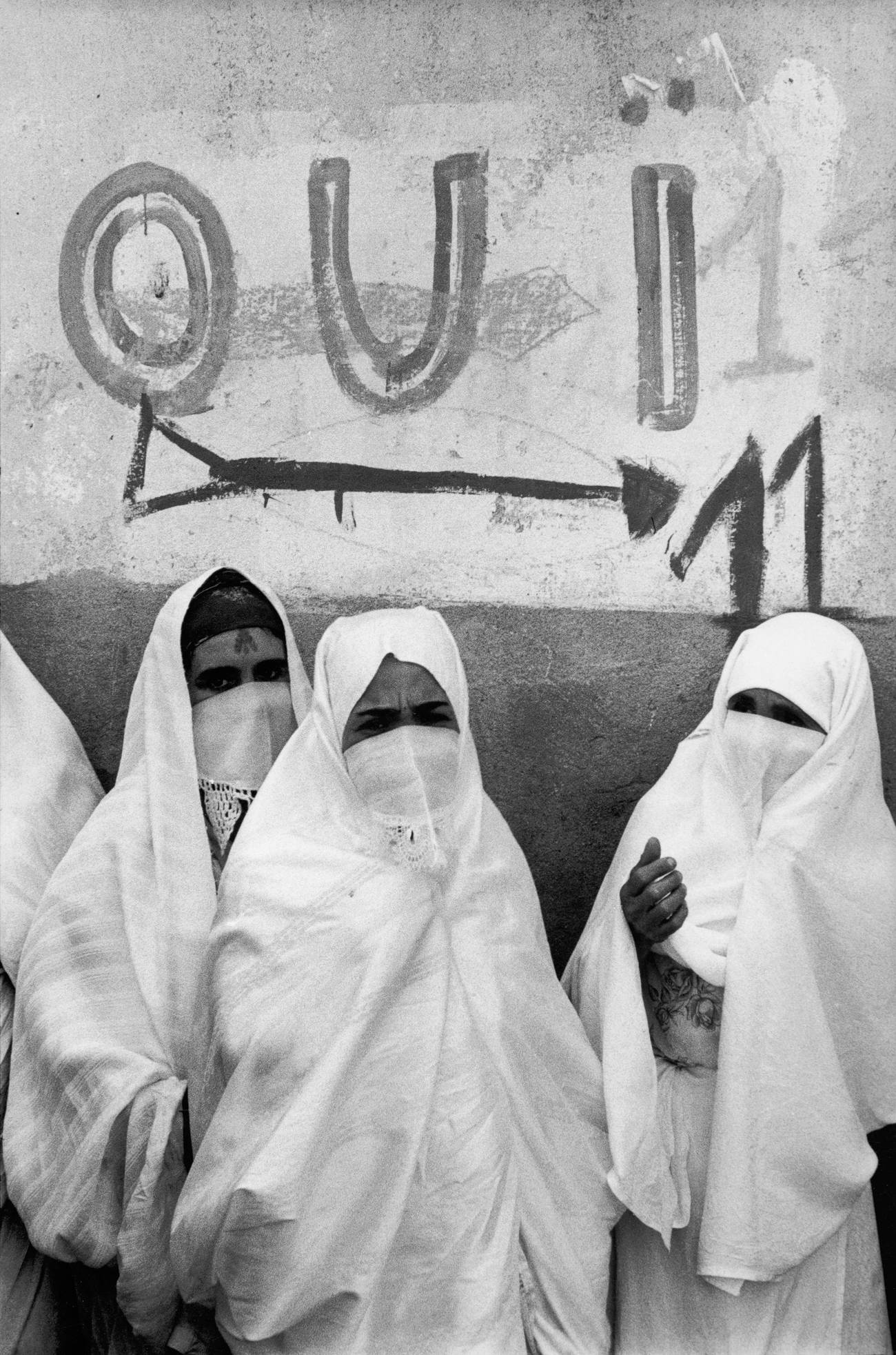

In France, what shapes our opinions is still the memory of two global conflicts from which we still haven’t fully recovered: first, the humiliation of the 1940 defeat; and second, the collaboration of segments of the French elite with the Nazi occupiers and then with Stalinist barbarism. The speed with which metropolitan France said goodbye to the empire, especially Algeria, in the early 1960s—forgetting about hundreds of thousands of pieds noirs (French settlers in colonial Algeria), Jews, and harkis, some forced to leave under the motto of “the suitcase or the coffin,” others shot, slaughtered, or crucified by the former colony’s new masters (the death toll is estimated at 80,000)—proves that the colonial enterprise was probably not as dear to the hearts of the French as some have said.

Decolonization was a veritable liberation for metropolitan France, a casting off of dead weight that coincided with the onset of a 30-year economic boom. We relieved ourselves of the colonies as much as they did of us. No one wanted to die for Tonkin or Mitidja once the revolution in lifestyles and the construction of Europe began in the Old World.

Among intellectuals, the most lucid on the question of Algeria was, as usual, Raymond Aron. The author of La Tragédie algérienne (1957) judged independence inevitable for economic and moral reasons. France was going to have to leave sooner or later and should manage the exit as wisely as possible. But whatever happened, it would be necessary to burn the bridges. It cannot be said often enough that the solution to some problems is to peacefully separate the parties rather than to push them into an unlikely truce that leads to war, which was the heart of the terrible conflict in the former Yugoslavia. Just as divorce was invented to settle differences between couples, you can’t force the citizens of a country to like each other, let alone their neighbors across the border.

President Emmanuel Macron is now considering making an apology to Algeria in the manner of Jacques Chirac recognizing the responsibility of the French state for the deportation of 70,000 Jews to death camps between 1940 and 1944. And why not? The step has its logic and has been mulled over at high levels of government for a long time. On the one hand, France should admit the reality of the dirty war, the terrible violence of the conquest (notably the burnings carried out by generals Cavaignac and Bugeaud), the denial of French citizenship to Algerians on the grounds that they were Muslims, the brutal repression of rebellions, and the French army’s use of torture, which Catholic writer François Mauriac condemned in Le Figaro.

But the apology should not be made without discreetly inviting the other party to reflect on itself. In other words, the Algerians should be urged to ponder the flaws of its “liberation,” to admit their share of dark behavior, the attacks by the FLN, the elimination by its militants of the other nationalist factions (especially Messali Hadj’s MNA), the conflict between rival groups that reached into the center of Paris and dug a “ditch of blood” within the immigrant community (Benjamin Stora), leaving nearly 4,000 dead and 12,000 wounded. Not to mention jihad and the foundational violence of the new republic, which, 30 years after independence, suffered a horrifying civil war that killed nearly 200,000 people.

This is not how things are likely to unfold, of course. Official Algeria prefers to claim for itself the role of the eternal pariah. President Bouteflika, after all, liked to evoke France’s “genocide of Algerian identity” and mentioned the existence of “ovens analogous to the Nazis’ crematoria” into which French troops allegedly threw hundreds of fellaghas. The metaphor of the Holocaust can be re-served with any sauce, especially in countries bottle-fed on anti-Zionism. Recall that Ahmed Ben Bella, Algeria’s first president, wanted to destroy Israel and, in 2006, congratulated himself for Osama bin Laden’s attacks and Hamas’ violence. The essential thing is to continue to point a vengeful finger at France to delay normalization.

Let’s lay it right out on the table: Algeria is the country that could least bear France’s apology, even as it pretends to welcome it. Because that would deprive the regime and its henchmen of the dividend of resentment that is indispensable for unity. It would oblige them to look their own history squarely in the face and to shine some light into the shadowy corners of their independence. France remains an Algerian obsession, whereas the opposite is not true.

To continue to be able to crush their people freely, too many ex-colonies seek in yesterday’s oppression excuses for today’s misdeeds. They are owed everything on account of the wrongs they endured. Apparently the “postcolonial” phase, having begun as it has, seems likely to last longer than colonialism did.

Perhaps a second decolonization, this one mental, will be necessary to change hearts and minds. What we should be asking of one another is to cut the umbilical cord and restart relations on another basis. We should stop reasoning in terms of debts or dependence. We should emphasize partnerships, not grudges, opening the way to solidarity and joint responsibility in serious crises.

Herein lies, perhaps, a spiritual revolution to be accomplished between Western Europe and the African capitals, a revolution that will be no less arduous than the first one. As for the substantive adjectives “decolonial” and “postcolonial,” they have the defect and disadvantage of suggesting a subordinate relationship with the old system, of confusing the rupture with the sequel, the secession with the continuation.

Less fearful than the virulence of our enemies toward us is the violence of the hate we have for ourselves. A segment of our own elites wants Europe to die. The continent has become a collection of divided nations laid out on the chopping board, on offer to the hungriest customers. The buzzards flock in to pull it apart. The division of the spoils has begun, with China, Russia, and Turkey as the top contenders. How many of our cities have already succumbed, at least in part, to the Shariah, gang rule, and erosion of the rule of law?

The situation brings to mind the prophecy of demographer Alfred Sauvy, who, in the last century, was already foreseeing the gradual disappearance of the Old World. He evoked the image of young people coming from elsewhere to close the eyes of old Europeans, beatific and sterile, administering to them a form of extreme unction. After contrition, the white man can look forward to extinction. It is time he took his leave, stealthily quitting the stage of history.

What can we say to that fraction of our intelligentsia who want the West to disappear, persuaded that its destruction will favor climate justice, the revenge of oppressed peoples, and the eradication of poverty? Simply this: after you. If you want to die, go right ahead. But let the rest of us live. Many of us prefer the fragile light of democracy to the shadows of suicide.

Translated from the French by Steven B. Kennedy.

Pascal Bruckner is the author of many books of fiction and nonfiction, including the novel Bitter Moon, which was made into a film by Roman Polanski.