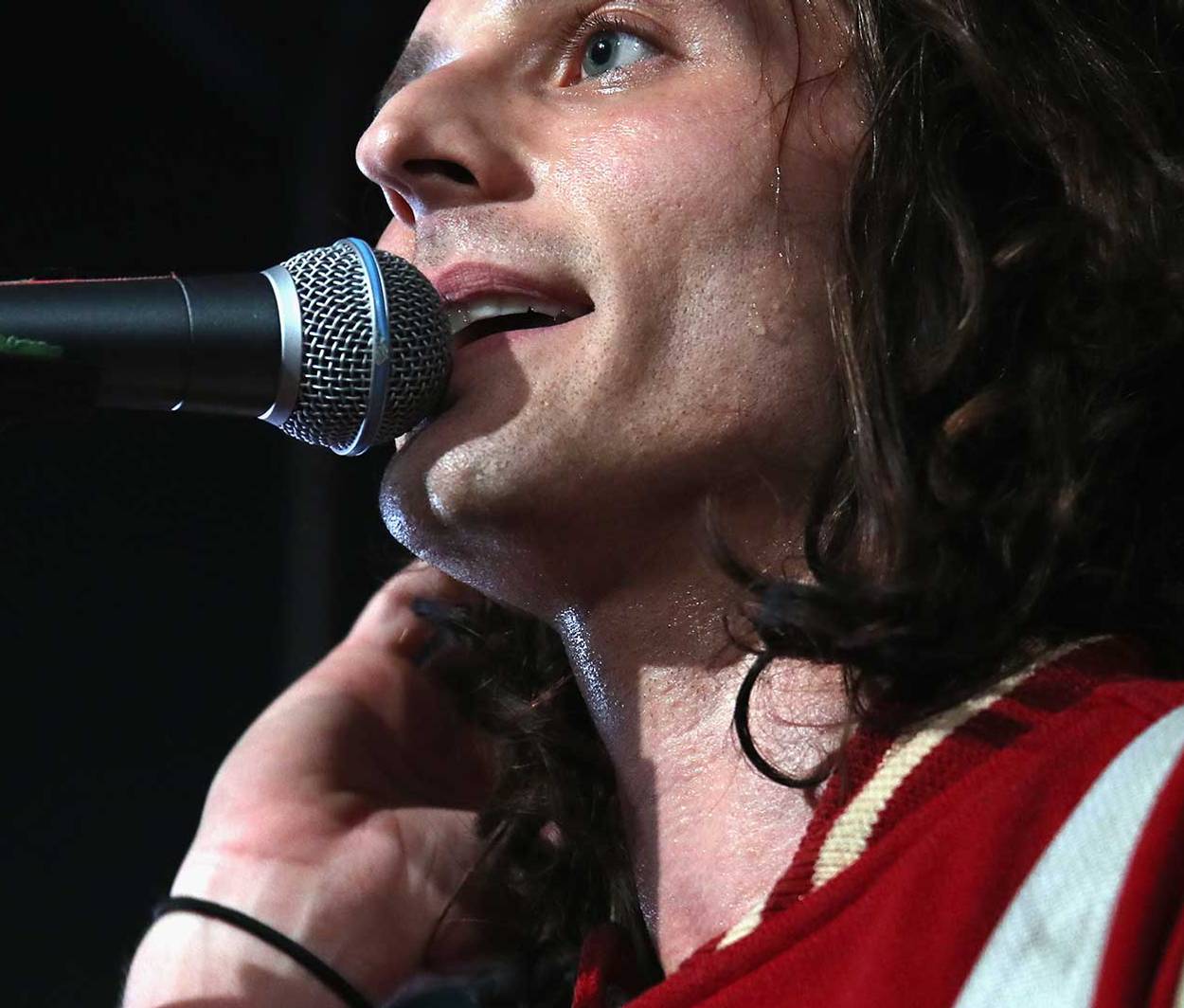

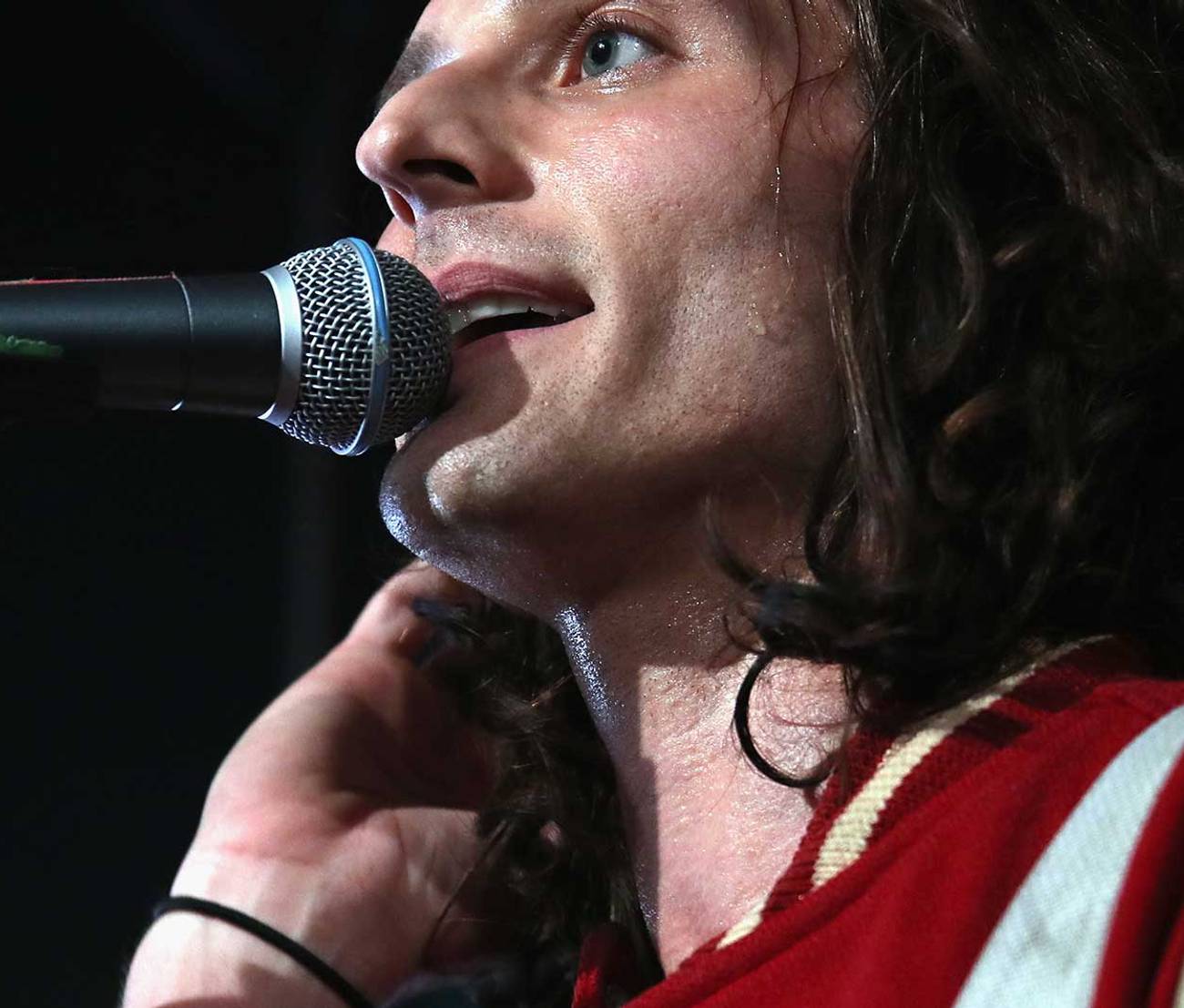

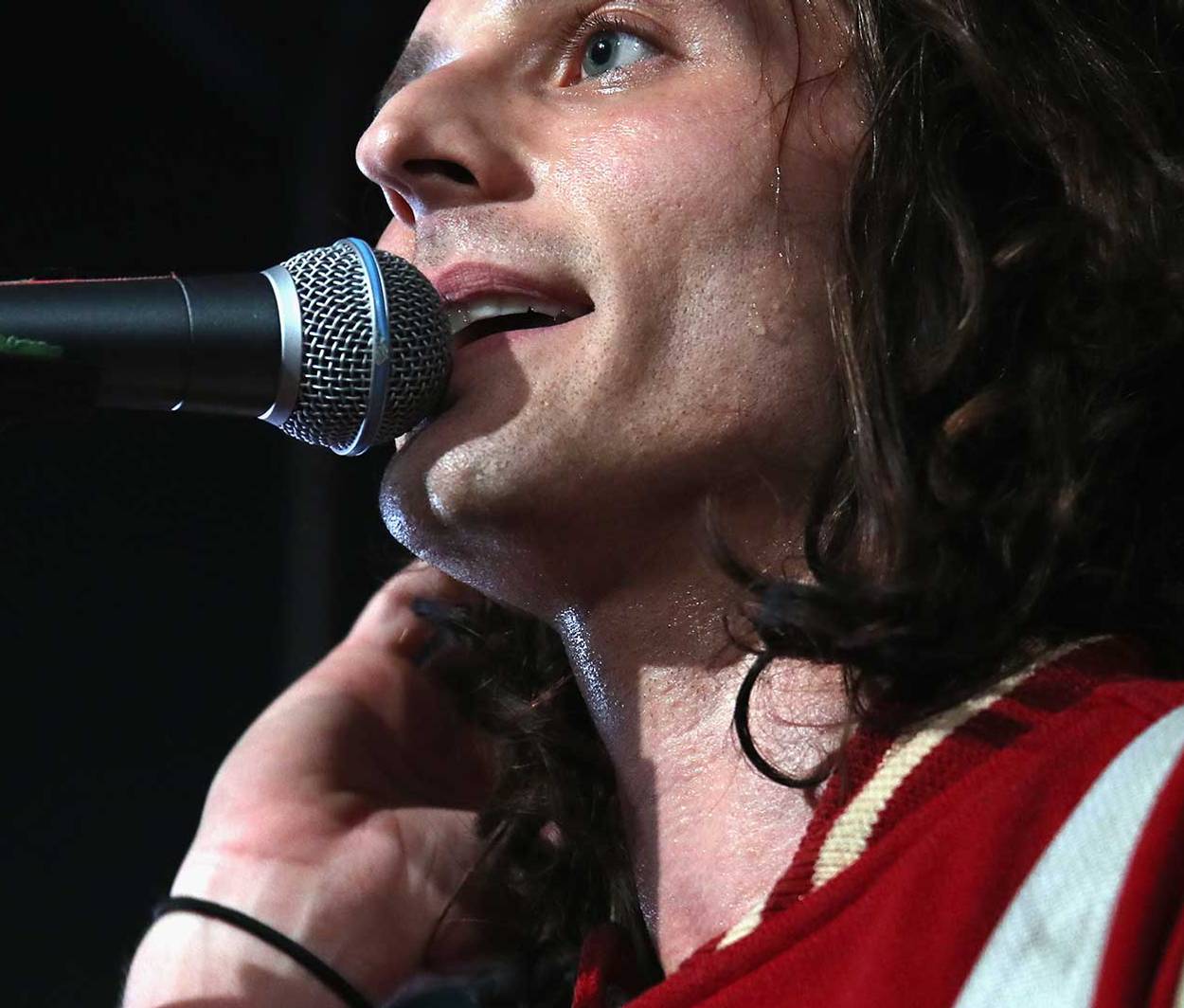

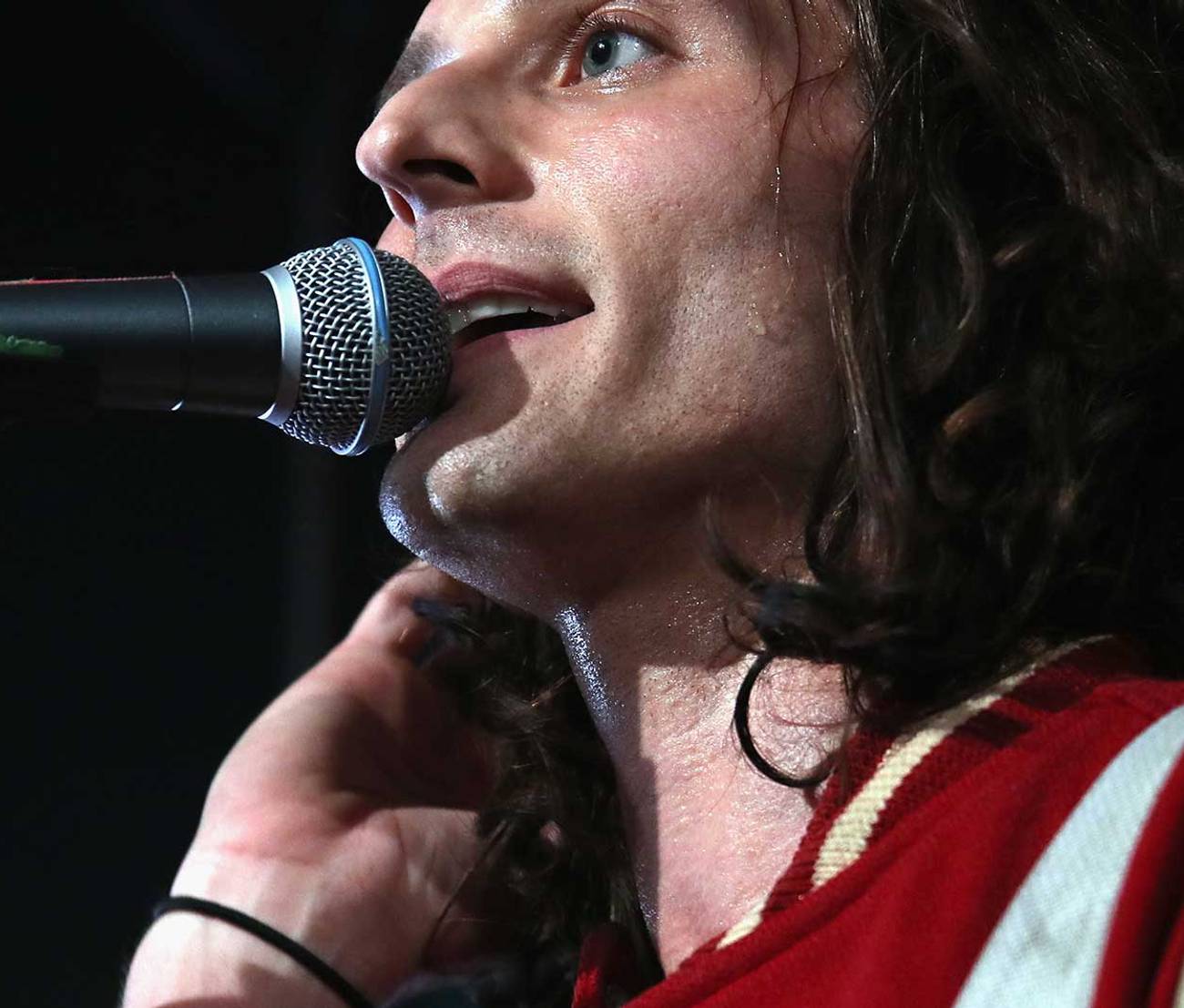

Q&A with Nick Valensi

The greatest living Jewish rock guitarist speaks about the Strokes, CRX, his North African Jewish father, his French mother, the import-export business, and getting his first Guns N’ Roses tape from Sam Goody

Even when they first started playing teenage bar gigs in Manhattan in 1999, the Strokes were already a throwback to a cultic time when rock bands offered meaning to tight-knit groups of believers who studied liner notes and publicity stills with Talmudic intensity and argued the minute differences in the inflection of individual notes in live and recorded versions of songs. The Strokes were A students. They mimicked the Velvet Underground, of course, with dashes of Oasis and the Stones, while practicing Axl Rose’s snake dance in the mirror. They understood rock as music and as fashion. What saved them from seeming like a calculated retro-nostalgia trip was the immediacy of their sound, which was anti-pop. They knew that rock ’n’ roll music was dirty, gut-level music that you listened to high or drunk, while making out with someone in a club.

Almost two decades later, it seems pointless to recount the history of the Strokes, other than to say that, in retrospect, they turned out to be almost as influential as the bands they admired. They made some great records, and they opened the doors for Jack White and other die-hard rock ’n’ rollers who snuck in just before the internet killed the music by destroying its mythology-cum-business model and reconfigured the music business as a shiny 99-cent jukebox for preteens and squares, courtesy of Apple.

But back to the Strokes. Having a favorite member of the Strokes was part of the package, the same way it was for the Beatles or the Stones or the Monkeys. My favorite was Nick Valensi, the giant, curly-haired guitarist who never did a solo project and whose dense, fluid style spoke to me through some common set of musical references that made it easy for me to imagine that we had grown up in the same place listening to the same records. Having spent some part of my later formative years in Paris, I even imagined that there was something French about his take on rock guitar: a cool distance that was both encyclopedic and whimsical. His wife, Amanda de Cadenet, was an accomplished photographer who in a previous life had been by far the most beautiful and seemingly the nicest of the very beautiful and often-photographed wives of Duran Duran, a band I loathed as a teenager. Duran Duran raised the specter of pop eating rock ’n’ roll, which was music that you had to truly feel to understand. The fact that the Duran Duran’s girlfriends were undeniably hot, and kept me up at night, only made me hate them more. It was possible, therefore, that Nick Valensi, in addition to being a guitarist for the Strokes, and a musical soulmate, was also an agent of rock-historical justice.

Just how prescient I was in at least some of my suppositions was revealed to me in the waning days of pre-Trump America, when I had lunch with Nick Valensi at a health food place in Los Angeles as he put the finishing touches on his first record without the Strokes, New Skin, which was released on Oct. 28, 2016. What follows is an edited version of our conversation about his father, Guns N’ Roses, France, his probation officer, his wife, his kids, singing lead, Jewish guitarists, and the mysteries of import-export.

Nick Valensi: The Strokes only do a handful of shows a year, which feels like a special thing. I like that, and it’s important to me that it stays that way. But at the same time, I started feeling like it would be really nice to just get on stage, even if it’s in a club with 300 or 400 people, you know. I actually wanted that. I wanted to have people right there, an audience right in front of me, as opposed to 40 or 50 feet away from me, on some big festival stage.

You’re a guitar kid.

Yeah. Growing up as a kid, I knew that I wanted to play guitar. And I learned it early on. And I always identified with the guitar player in the band, you know. I wasn’t looking at Axl and wishing I was him. I was looking at Izzy and Slash.

That’s a particular type of kid, right?

The same way it’s a particular kid who looks at Axl or looks at Kurt Cobain, and is like I want to be that guy.

So being a lead singer on your own record must feel a bit weird.

I resisted singing for a long time. It was just never an urge that I had. And then, about 2, 3 years ago, something came over me and I got the bug really bad to get on stage and start performing and start playing. I’ve been writing songs for a while, but always with another first voice in mind, always with the intention of having someone else sing on it. And I guess it just dawned on me that I had to sing on the new batch of songs that I was writing if I didn’t want any obstacles in the way of kind of going on tour and playing live.

What else was going on in your life that you suddenly felt like you wanted to hear your own voice?

It wasn’t specifically about my voice, to be honest with you. It was about feeling like I wanted to get back in the game. The singing thing was a hurdle to overcome for me because, like I said, I never really wanted to be a singer. I wanted to get on stage and just fucking do this. So I thought, “well, I gotta sing, I gotta fuckin sing.” So I started learning how to sing, and practicing, like singing into my laptop or headphones everyday, learning how I wanted to sound, learning what I wanted to say.

How weird was it for you as you’re coming up with a riff and then fucking around with the parts of a song, putting it all together in your head and maybe putting those elements down on tape, to imagine that the voice was going to be your voice, no one else was going to be that instrument for you? I can imagine that could freak you out.

It’s still a little weird, you know. I think everybody has that thing where when you hear your voice back, it sounds unpleasant. And I’m still dealing with that feeling inside a little bit. But just going off what other people say, other people seem to like it.

I was pleasantly surprised, to be truthful.

That’s the feedback I’ve been getting, which is good, you know. I’ve wanted to pleasantly surprise people. And at some point it kind of turned into working on this record that was initially meant to be a vehicle to go on tour. At some point, it started to feel like maybe it was more than that and actually like a cool recording. And you know, I started to feel like, shit, my voice is sounding alright!

Those are some pretty fucking good songs. But why shouldn’t they be good, right?

Right, yeah—and then that feeling kept on getting cemented, with Columbia Records being interested, so it’s been like, “Wow, shit, this is turning out to be bigger than I ever thought it would be,” which is great.

Tell me about that feeling of being a little kid and wanting to play the guitar so bad. What drove that?

I, you know, I’m, I’m probably an anomaly, in that I was that kind of kid who literally at 6 years old knew what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. And it was, play guitar in a band, a rock band.

Where did you hear a guitar?

My dad. My dad played. My dad passed away when I was 9, when I was young, really young. But my dad always had a guitar in the house, so from the time I was born there were instruments in my house. My dad wasn’t a professional musician by any means but he was—

Expressive.

He played guitar. I always remember there being an acoustic guitar in my house. And then it was around the age of 6 that I saw the “Welcome to the Jungle” video on MTV.

Haha.

And that was it for me. I got my uncle, who was like kind of a cool uncle, I told him about this thing that I had seen on television. He was like, “Oh yeah, I know that band, they’re huge right now and they’re blowing up.” And he was like, “We can go to the Sam Goody.” You remember Sam Goody?

Yeah, sure.

He said, “We’ll go to Sam Goody and we’ll get you the tape.” And I was like, I love that. So after school, he took me, he bought me the cassette tape. And at first, I was listening to it in my house. But then I got to track 2 and realized there was like a bunch of F-bombs, curses all over that record, and weird sexual innuendo that I couldn’t even really comprehend.

So that was my thing that I listened to on headphones, in the Walkman. I remember going on like family vacations to wherever, and just being like a 6-year-old kid inside my Walkman the whole fucking time.

It’s sweet because no one’s guessing what’s going on inside that little kid’s head. “You’re in the jungle, baby!”

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Tell me about your parents.

My father was born in Tunisia. He was a Sephardic Jew. Tunisian-born and raised. He ended up moving to Paris to go to university, and then after university, he ended up moving his whole family from Tunisia to New York. There was a kind of mass exodus of North Africans in the ’60s to Miami, New York, Los Angeles, all over.

Did he identify with French culture, Arabic culture, Jewish culture?

All three of those, very strongly.

Mhhm.

My dad was really, deeply religious.

Right.

We grew up going to synagogue every weekend. And on high holidays, even the kids had to fast, while my mom would be like sneaking us stuff.

Haha.

I think my father identified first as Jew. And then, Arab or French, probably 50/50 between those two, I would guess. But I was 9 when he passed away, so for me to say—

—that you knew him—

Yeah. I barely knew the guy. As an adult, there’s more stories that you hear from relatives and stuff.

Did he raise you with that Sephardic North African culture?

I don’t know what part of, like our Sabbaths, for example, in terms of the food we were eating, I don’t know what part of it is like all Sephardic Jews eat stuff like this, or what part of it is specific to my weird Tunisian Jewish family? But there was like weird stuff like fuckin’ egg cakes with chicken in ’em and shit.

My wife is a Sephardic Jew, from Greece.

Oh is she? I remember my grandma making—I loved it as a kid—it was basically like a fucking cake, like a savory cake made with eggs, chicken, and noodles. Do you know what that is?

I will ask my wife. Did your grandma make that awesome North African spicy fish?

Yeah, she made a great fish. She made great roast chicken, too.

Where is your mom’s family from?

My mom is from the south of France. She was born into a Catholic family and converted to Judaism upon meeting and falling in love with my father in the mid-’70s in New York. So she is a French woman, who grew up on a vineyard in the south of France, close to Bordeaux, all wine farmers and shit. She grew up there, and she ran away from home when she was about 16, moved to Boston, then fucked around for a little while then moved to New York. Ended up meeting my dad, and my dad was, like I said, deeply religious and his family was as well. And they dated for a few years, they fell in love.

He really wanted to marry her but he couldn’t do it unless she was willing to kind of go through this whole thing and become Jewish. And she did!

Do you think that was, in the end, a happy thing for her? Was it a sad thing? Emotionally, how did you feel she related to that choice?

Well, it’s hard for me to speak on her behalf, but I’ll try. I think that she grew up being a little bit traumatized by religion in general, like a lot of people.

Yeah.

So I don’t know that it’s something that she would have done without falling in love with my dad, this devout Jewish guy. But for her, I guess love trumped whatever else was going on and she was willing to do it. It’s probably pretty telling that after my dad passed away, all of our Saturday trips to shul and our Friday night Sabbath and that stuff tapered off within a few years.

Did you miss it as a kid?

No.

That was him, but now he’s gone?

I think it was like that, yeah. You know, I grew up being close to my uncle, who bought me that GnR tape. He was my father’s brother, and he was also a pretty devout Jew. And my father’s side of the family, who all moved to New York with him at the same time, they all lived within a couple blocks from me growing up—as opposed to my mom’s family who all stayed in France. She actually ran away from home.

There is something pretty radical about a French woman of that time and place being like, “I’m going to fall in love with the double other.”

With this Arab Jew.

Right.

I know. Dude that’s—

Hot.

Yeah, it is fuckin’ hot. That’s bad. And yeah, her family was pretty bummed about it for a long time.

What did your father’s brother, that side of your family, what did they do for a living?

I don’t know. I grew up with a kind of family that, a lot of the time, I didn’t know what they did for a living. When I would ask, and they would say, “Oh, we import things and we export things.”

Import-export.

And I never knew exactly what that was. Still, to this day, I don’t know. But I’m pretty sure it was shady.

Right.

So I don’t have a good answer to your question. Basically, I’m pretty sure that it was some illicit, illegal shit. But I don’t know exactly.

The whole culture of import-export among Sephardic Jews is some deep shit. I think there’s a lot of kids from New York in the ’70s and ’80s whose parents gave them that same answer: Import-export. Now shut it.

What my dad did throughout the ’70s and most of the ’80s, I really don’t know. But at a point, I want to say ’84, ’85, he went straight, so to speak, and opened up a French restaurant with my mother, Cafe Bonjour on 67th and Lex. After my dad got lung cancer and passed away in ’90, my mom had to shut down the restaurant for a little while for some tax shit. There was loads of weird shit going on with my dad. But she kept the restaurant opened up under a different name. And still has it.

How did you get through your dad dying as a little kid?

That’s a good question. Barely. I wasn’t lucky enough to be provided with help dealing with the inevitable emotions that a kid will have when losing a parent. There weren’t a lot of people who walked me or talked me through that. So what ended up happening to me was, I went through my adolescence pretty shut down emotionally.

Did you listen to music a lot?

Yeah. I listened to music a lot and a smoked a lot of weed.

I can remember at that age having family problems, and feeling like there was no safe place to be, which is really scary when you’re little.

A lot of kids go through that.

Right?

It’s tough.

It’s a part of my life that I hadn’t really thought of that much but now I have a 10-year-old son who’s the age that I was when my parents were going through that shit.

Yup. I have 9-year-old twins. And my kids are at the age I was when I lost my dad.

Isn’t it intense to look at those little kids, you do your best to make sure their life is so perfect, and then to imagine that’s what you were then, when those formative emotional experiences happened and crashed your whole inner world?

Fuck, yeah. To think that’s what I was, and then to think a year later, the most traumatizing thing in my life happened. I was getting into all kinds of trouble by the time that I was 11, stuff that 11-year-old kids have no business getting into and knowing about.

What did you do when you were 11?

I got into drugs and alcohol, you know. I got arrested a few times. I got arrested when I was 11 for trying to take another kid’s money and his bus pass. At the time, the bus pass was such a hot commodity.

Ride anywhere for free.

I tried to take this kid’s bus pass and like a couple of bucks that he had. And long story short, I got fuckin’ arrested. And had to go to family court and had to have a probation officer for a year. It was a crazy, crazy thing to do to a kid.

But that must have been boss in school though, being the kid with a probation officer.

No, it wasn’t. I had to go to a probation officer once a week and it was fuckin’ awful. It was all the way downtown, by City Hall. It was a fuckin’ drag. It was really bad.

You were like, “Maybe I’m not cut out to be a hoodlum.”

I am definitely not cut out for a life of crime. Definitely not.

And at what point did you get serious about music?

I was always serious about music, to be honest. I guess maybe a more revealing question is like, “What are the times when you weren’t into it?” Because there were a couple of points in my life, maybe right around the time that my dad passed away as a matter of fact, where I put the guitar down for a year or two. Just put it down. Not that I didn’t play sometimes, you know. I mean, I’d play some songs. But it wasn’t something that I was pursuing seriously.

There’s probably only one or two instances in my life where the guitar wasn’t something I was consumed by.

It’s funny, when I listen to you play, you can hear that omnivorous head you bring to your instrument, there’s just so many quotes from different guitarists and different licks. It’s really heady and dense, while you keep it very fluid and dexterous at the same time. It’s like you’re just saying, “I know you are thinking this is like this other song, so I’m going to quote that other song for two notes, so we’re all on the same page, and then I’m moving on with the thing that I am doing right here and now.”

Right.

It’s not imitative note-for-note, it’s almost scholarly and Talmudic, in some fucked-up, ADD-obsessive way. And conversational.

Wow.

Yeah. I find with so many guitarists I hear now, their actual frame of reference is pretty narrow. Really they’re interested in simply completing the bare-bones logic of the track.

No, I’m not like that.

You’re very heady and you’ve got a very, very broad frame of reference within the genre. So listening to you play is also like having the best conversation about all the guitar-driven rock that you liked and that I liked and listened to when we were growing up.

Well, first of all, that is a massive compliment, so thank you. I’ve listened to a lot of music, so I have a pretty good vocabulary there, I guess.

It comes from being that guitar kid, and being serious about it. And having that be your main language.

Yeah. The thing about being a kid and knowing so clearly what you want to do is that you have really no other options from an early age. So, I’m not a dummy by any means. I ain’t no fuckin’ dummy! But I was not interested in school at all. I was a pretty good student up until third grade. After third grade, it was bad. I just wasn’t interested.

But every once in a while I’d connect with an English teacher or a social studies teacher, I’d connect and get an A, and I’d learn a lot of cool stuff. And then next year, the different teacher comes in and it’s like, I’m out. I’m not into it. And that’s probably because I had this conviction that I’m going to do music. I never wanted to do anything else, so I never really pursued excellence at anything else.

Having that one thing you’re obsessed with can be hard. But to be honest, I think it’s the best goal that humans can have. To pursue excellence. Being good at five things, getting good grades, go to law school, at a certain point you lose track of yourself and become a widget.

You see kids who, they, you know, they’re graduating high school, going into college, don’t really know what to do. OK, well, we’ll get you into a liberal-arts school, and you’ll go and you’ll have four years, you’re going to figure out what the fuck you want to do. And then, after the four years, they get out with their bachelor’s degree in liberal fucking arts, and they still don’t know what they were ever passionate about. You get people who were 25, 30, 40 years old, who were, like, doing a thing that is not their thing, so maybe they will try something else. And when I see that, that’s when I feel really grateful.

I had to explain to my kids that just because we skipped the Seder this year doesn’t mean we’re not Jewish, because being Jewish is more something that’s in your bloodline.

I thank God this thing struck me and I just knew, because I’d hate to be in limbo like that.

I have a ton of friends who have a job, a good job, pays well, and you know they’re doing alright. They go to work and clock in and they clock out, but it’s not what they really want to be doing. And then when you ask them, what do you want to be doing? They don’t really know. And that seems really hard.

I feel like you just wrote a Ray Davies song.

[Laughs.]

Do you spend much time in France? I love it there. There’s something French about your playing, too. Le Rock.

Growing up, I did spend a lot of my time in France. Every summer from, literally from the year I was born, I’d get shipped off to France. I’d be there from the day that school let out until the day before or a couple of days before it started. So I’d spend about three months out of every year in the south of France, on a vineyard, chasing snakes and riding mopeds and fucking drinking wine.

It’s a total flip, right, from the rent-controlled apartment on Second Avenue. They’re polar opposites.

Oh, it was so weird, man. And when I was growing up, I knew that not everyone had an existence like that. I was a little embarrassed of it, I guess.

You know, when you’re a kid, and your parents are both immigrants, there’s kind of this weird, not shame exactly, but you just want to kind of fit in with the other kids, to have a normal American family. And my family was anything but American or normal. So there was kind of a weird feeling about really exposing who your family is. It wasn’t something that I was keen to advertise to my friends at public school in Manhattan.

Right.

It wasn’t until adulthood, actually, that I was able to reflect on that, and think, how fucking cool, you’re a kid who got to grow up in Manhattan and then you’d go to fuckin’ Bordeaux?

Do you spend time in France now?

Not a lot. I love going to France. But I guess between the ages of 18 to 26 or 27, I traveled so much on tour so I just don’t travel that much anymore, to be honest with you. Traveling often feels like work to me, and I am, at heart, a homebody.

Me and my wife, sometimes we’ll have disagreements about this because she likes to travel and she wants the family to travel. And of course I understand that, and I see the value in it. But I’m kind of like, well, I’ve been there and done that, and now I don’t want to go to fuckin’ Europe this summer, I like it here, in our house.

My parents are both French speakers, they grew up in Montreal, and I spent some time working in Paris. I publish my stuff there. I feel connected to those readers, especially recently, even though I hardly think of myself as French. But culturally, I am part French, I guess.

Yeah. Well, you know, I don’t think you have to pick one or the other. I identify more as an American person, but my mom’s from France. I have a whole side of my family there and I spent a lot of time there, formative years growing up. So I’m not going to disavow that culture, but at the same time I don’t need to—what’s the right word?—embrace it wholeheartedly, at the expense of something else. There’s an in-between.

Do you speak French?

[In French] Like a 6-year-old child who is learning the alphabet and reading baby books.

You speak French-Canadian French.

[In French] Parisian waiters have said so, certainly.

Right. I do still get the Parisian waiters who, I’ll go into a restaurant and I’ll order in French and I guess my accent isn’t up to snuff for them and they answer in English. I feel like, “Fuck you. Let me order my coffee in French. I spent all my summers here when I was a kid. I’m just doing my best, man.”

I took my daughter to Paris this summer because she’d never been. And the cool thing is that all those waiters were suddenly so nice to me. It turns out that waiters in Paris are incredibly considerate and nice to you if you have a reasonably well-behaved child who speaks even three words of French.

Is your daughter reasonably well-behaved?

Yeah, she is now. She found art. Drawing, studying, learning some technique, and knowing she can be good at something, has given her confidence, which she lacked when she was really little.

Humans get bitchy and mean when they’re not confident, when they feel shitty about themselves.

We went to MoMA one day, and I always played this game with them like, What are your three favorite paintings in this room?

That’s a good way to get the kids talking.

Right? And my son, who is super-bright, but a reader, not so visual, was like, I like the one with Napoleon on a horse, or whatever. And my daughter’s like pointing at the Rothko and a Klee. Then we did a few more rooms and suddenly I was like, she likes all the shit that I like because she has that head. So I was like, “Do you like the paintings?” And she’s like—

“Yeah, I like them a lot.”

So I was like, “Would you like to learn to draw?” And she was very happy about that idea.

Wow. My daughter takes art lessons as well. It’s good. How old is she now?

She’s 7.

Cool. That’s great. My daughter is the same way. And is taking art classes over the summer for her technique and stuff but also they go to the museum and talk about shit at the museum, so there’s like art history, art appreciation, art technique. She’s pretty good.

My son’s obsessed with sports. Obsessed.

Are you any good at sports?

You know, I’m all right.

Really?

Ok, I’m not good. It’s not something that I was ever really that interested in. As a kid, I played a little bit of basketball growing up, but you know, I’m a fucking giant so I could always get rebounds and kind of block people out.

But he’s got the skill, physical grace that I never had. I’m way more clumsy than this kid.

You’re an All-Pro guitarist, man. You’re coordinated enough.

Yeah, but that’s different, you know. That’s like a fine-motor thing.

And what’s weird about me is that I can play guitar pretty well. But then my kid will ask me, “Can you undo this double knot?” and that fuckin’ drives me crazy. I have to call my wife in for the double knot.

You trained all your muscles and your attention toward that one goal.

It’s weird, it’s weird. My wife talks about it a lot. She’ll ask me to take off her necklace at the end of the night or whatever, and my fucking fingers, literally, I can’t grasp the thing. That’s weird.

How do your kids connect to all places that you’re from, that your wife’s from? Do you present that all to them in some kind of frame?

We don’t really curate that. I mean, my kids, they know their grandma is from France and speaks with a pretty thick French accent. And my wife’s mom and father are both from England. How they identify with French culture or Jewish culture or British culture is not something that has been particularly important to us, to be honest with you. That’s not something I think about.

Do the kids think about it?

I’ve had conversations with them about Judaism because, you know, they asked me. We speak about Judaism and Jewishness pretty regularly. We’ve had that conversation many times.

There was a time when they were like, “Oh well, because, you know, Dad, you’re Jewish.” And I had to be like, “Well, you know, no, because we all are, really, because we’re a Jewish family.” I had to explain to them that just because we skipped the Seder this year and just because we don’t go to synagogue every Saturday doesn’t mean we’re not Jewish, because being Jewish is more something that’s in your bloodline. You don’t really choose to be Jewish or to not be Jewish.

It took them a second to wrap their heads around like, “Oh, OK, we’re Jewish, but we don’t really do many of the Jewish things.”

The thing that I’ve felt with my kids that disturbs me is that there’s an energy around the Jewish thing that’s heightened now. If you say the word “Jewish” to someone, you can see there’s some big internal reaction. It’s not normal to them.

But that’s been going on for decades, I feel. You grew up in Brooklyn Heights, right? Did you go to private school?

Yeah.

So you probably went to school with other Jews. I was the only Jewish kid in my elementary school. Literally. Puerto Rican, Irish, Italian, yeah some Asian kids also, who probably didn’t get it any better than I did.

Kids were mean to you about Jewish shit?

There was a lot of that, yeah. When you’re the only Jewish kid in the school, it becomes a thing and then you just try to keep that quiet. Inevitably that’s what ends up happening. But it’s weird to grow up in New York City and to be the only Jewish kid in your school. Where is everyone else?

I feel like there might be some particularly religious people that grow up learning that Jews killed Jesus Christ. And that’s not what Jewish kids are taught growing up, obviously. So there was a point in my tween, pre-adolescent years where I dealt with that too. Your fucking people killed Christ. And I was like, “Wait, what?” I haven’t heard about this. Is that a fact? Hold on a second, let me take this to my parents, let me take this to my rabbi.

We pretend that that shit doesn’t happen anymore because we want to feel normal. Except it happened to you. It happened to me. It’ll happen to your kids and my kids, in whatever form. That’s the truth.

It’s been going on for millennia.

Why should it stop just because we want to be normal?

Yo, does Tablet Magazine do a lot of pieces on musicians?

I wish we did more. But it’s my wife’s joint, you know.

Do you know why?

You tell me.

Because there’s not a lot of Jews in rock music.

Well, the one out here who has been really nice to us is Leonard Cohen, who is a sweet person, and a great songwriter.

He lives here? I would love to meet him. I’m a huge admirer. I’ve loved his shit literally since I was 13, 14 years old.

I will do my best to hook you up. But he’s been very sick recently. I hope he will be OK.

And there’s Bob Dylan, of course. He’s Jewish.

Sure. And who else do we have? David Lee Roth?

Diamond Dave.

Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley.

Right.

Who else have we got?

Um. Pete Townshend isn’t Jewish, despite his nose. Slash isn’t Jewish, either.

Just the fact that we’re struggling here tells you that there’s not that many.

Especially there aren’t that many great Jewish guitarists. Mike Bloomfield.

Mike Bloomfield, yeah, I didn’t even know he was fucking Jewish.

He was a real-ass Jew.

I did not know that.

If you’re looking for greatest Jewish guitarists.

Well, I would like to carry that mantle.

It’s yours.

No one else is here to take it.

David Samuels is the editor of County Highway, a new American magazine in the form of a 19th-century newspaper. He is Tablet’s literary editor.