About half way through Jews Don’t Count, the most influential recent book about Jewish representation in Great Britain, British comedian David Baddiel writes, “I kind of think ‘Fuck Israel’. … I don’t care about it more than any other country, and to assume that I have to have a strong position either way on Israel is racist.” Baddiel cites the biggest influences on his own identity as the American Jews Jerry Seinfeld, Saul Bellow, Groucho Marx, and Philip Roth. He concludes, “None of that has anything to do with a Middle Eastern country 3,000 miles away.”

Amid generally glowing reviews, some critics raised an eyebrow at Baddiel’s insistence that Israel had nothing to do with him—or even, by extension, British Jews more broadly. “Baddiel’s affinitylessness with Israel … severely weakens his analysis of antisemitism,” wrote Booker Prize-winning novelist Howard Jacobson. “One cannot claim to grasp the nettle of Jew-hating if the psychology of its most potent contemporary expression … doesn’t interest you.”

Baddiel’s “affinitylessness” can easily be seen as wishful thinking or as evasive: It’s hard to see how Israel, as the world’s only Jewish state and as a magnet for antisemitism, can truly be irrelevant. But his sentiment, so casually delivered, begs the question of whether it is part of a bigger culture of denial, disavowal, and even disinterest where Israel is concerned, and where that culture comes from.

Read more on Jews in England

The numbers do not point to widespread disinterest in Israel among British Jews: While 70 percent are critical of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, and two-thirds feel a sense of “despair” every time settlements are expanded, according to a U.K. pro-peace organiation called Yachad, the number of those who still see Israel as central to their identity has remained high. In 2010, a Pears Institute study found that 82 percent of Jews in Britain say Israel is central to their identity; another survey from Jewish Policy Research, conducted between 2010 and 2022, reinforced this finding. Moreover, the election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party in 2015 forced a nationwide conversation about when, and how, anti-Zionism could shade into antisemitism. The controversy has not died down; this month saw the publication of Israelophobia: The Newest Version of the Oldest Hatred and What to Do About It by Jake Wallis Simons, the editor of The Jewish Chronicle.

Baddiel’s “chill, man” approach to Israel is the polar opposite of the polemics and division stirred up in recent years, in part by Corbyn. The far-left anti-Zionist group Jewdas, founded in 2005, hosted a seder attended by Corbyn and branded Israel “a steaming pile of sewage which needs to be properly disposed of.” Speaking to the media collectively as “Geoffrey Cohen,” it has organized Birthwrong tours to Andalucia to parody the Birthright movement. Yet at the time of the Corbyn seder, Baddiel downplayed the malignancy of this political outfit: “They’re just Jews who disagree with other Jews”.

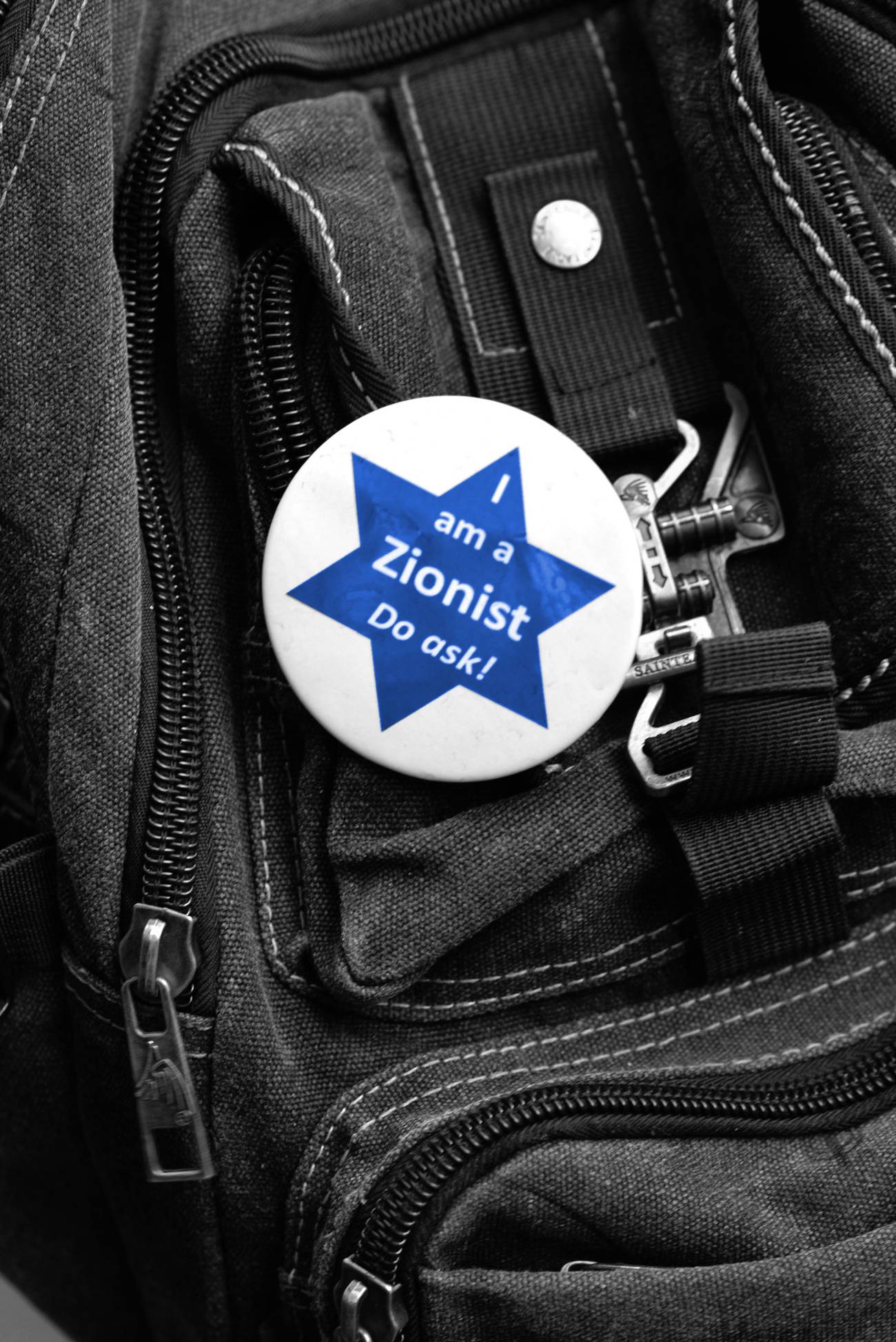

In some ways, the extremism of Jewdas is more familiar, and better understood, than Baddiel’s quiet disavowal. That’s because we associate the defenders and critics of Israel with strong expressions of feeling: The modern history of antisemitism has often been written through descriptions of those on the fringe, including the anti-Israel extremist fringe. In his new book, Harvard professor Derek Penslar refers to Zionism as an “emotional state.” If on the level of ideology Zionism remains highly protean and subject to competing definitions, its animating power comes from “bundles of feeling, whose elements have varied in volume, intensity, and durability across space and time.” The same applies to anti-Zionism, says Penslar: Even those who most loudly decry the state of Israel can’t help but show how much they care about it, often to the point of singular obsession.

What to make, then, of those individuals who take an “affinityless” stance? How is the public distance from Israel related to other denials of Jewishness, such as the psychological type described by Isaac Deutscher as the “non-Jewish Jew,” and the pursuit of assimilation into wider British society? In a 1980s interview with chronicler of Anglo-Jewish culture Stephen Brook, the acclaimed director Jonathan Miller confessed candidly, “I don’t feel the Jews are my people. The whole idea of a people is totally repulsive to me.” He continued, “I have no interest in Israel at all. I mean, I’m interested in not seeing it obliterated, not because of the Jews, but because I don’t want to see any civilized country go by the board. On the other hand, I wish it were a little more civilized.” On visiting the country, he claimed that he only felt at home at an atheistic kibbutz (his wife surmised this was because it resembled Bedales, the liberal boarding school of Miller’s youth).

The growth of anti-Zionist sentiment on the British left was especially acute in the early 1980s, shaped by the condemnation of Zionism as a form of racism in the United Nations General Assembly in 1975, the victory of Likud in 1977, and the fall-out from the first Lebanon War. For the New Left, it became more common to conceive of Israel less in terms of the anticolonial struggle for independence and more as an embodiment of settler colonialism. But there was nothing predetermined about this political realignment. According to historian David Feldman, it was difficult for many on the left to let go of the belief that Israel embodied the victory of the same democratic and progressive values cherished in Western Europe. Although he had resigned from Labour Friends of Israel two years previously, in an interview in 1984, the socialist politician and activist Tony Benn still refused to equate Zionism with imperialism. “I am in favor of a Jewish state,” he told one interviewer, “and I believe the Jews are entitled to have security in Israel.” (By the mid-2000s, Benn was vocally scathing Israel, and he was a prominent patron of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign).

Anti-Israel sentiment also took a long time to surface within the postwar Anglo-Jewish community. Identification with the fledgling state had reached its peak in the late 1960s, after the Six Day War had raised the prospect that Israel might be wiped off the map. For a generation that had lived through the Holocaust, the threat of annihilation, even “a second Auschwitz,” as historian Bernard Wasserstein put it, was a spur to action: There was an outpouring of public meetings, demonstrations in solidarity, and charitable donations (the emergency committee raised £11 million). “Only in 1967 did concern for and identification with Israel’s fate become central to what it meant to be a Jew in Britain,” writes historian Todd Endelman. “It then became the most potent force for keeping Jews within the communal fold, as well as bringing back the estranged and apathetic.” Supporting Israel in its hour of peril mobilized the increasing number of Jews who no longer felt religious identification.

A youth demonstration against Palestinian actions in Israel during the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, London, 1974McCabe/Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

From a longer historical perspective, the cooling of feelings toward Zionism in the 1970s and 1980s returned Anglo-Jewish public opinion to its prewar mixture of passion and ambivalence. While Zionist leader Theodor Herzl received a warm reception among migrants in the East End, the British communal elites on whom he pinned his hopes for funding his grand schemes proved to be uninterested in his appeal. Following a meeting with Alfred de Rothschild in 1902, Herzl wrote in his diary, “How is one to negotiate with this collection of idiots?” Although London was the birthplace of the Zionist Federation and hosted the Fourth Zionist Congress in 1900, the idea of a Jewish home in Palestine remained marginal and divisive among the British Jewish leadership in the years before the First World War.

For the interconnected elite of Anglo-Jewish families known as the Cousinhood, who had dominated communal institutions for decades, Herzl’s proposals seemed at once impractical and dangerously subversive. These representatives of old British Jewish families were immensely proud of the progress made by Jews in Victorian Britain over the decades since emancipation. They were loath to jeopardize these gains by backing a policy that would suggest that Jews were something other than loyal British subjects.

Equally, for the Anglo-Jewish intelligentsia, like historian Lucien Wolf and theologian Claude Montefiore, what was at stake in the debate was the destiny of the Jewish people. Rather than a political nation, the Jews were primarily a spiritual nation whose mission was universal and committed to the emancipation of all mankind. To substitute this for a narrow form of territorial and ethnocentric nationalism could only seem regressive. To Israel Abrahams, a key thinker in liberal Judaism, the very idea of a Jewish, territorial nation-state smacked of a return to the ghetto.

With the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and the creation of the British Mandate for Palestine, the geopolitical situation changed: A new alignment was formed between Zionism and British imperial patriotism. Many, however, were left unpersuaded. Non-Jews fretted over how to square the promises to Chaim Weizmann with promises made to the Arabs, while the administration of the mandate frantically tried to put the brakes on Jewish immigration into the colony. Many of the old Jewish elites continued to view Zionism as a serious threat to their place in Britain—especially in the wake of anti-communist paranoia. The League of British Jews, which they founded in 1917, poured vitriol on the Zionists, but it ultimately folded in 1929.

It is true that on an institutional level, the ideological hold of the Cousinhood was broken in the 1920s and 1930s, as a new cohort of wealthy Jews, the children of migrants from Eastern Europe, seized control of communal institutions. Still, for much of the interwar period, Zionism remained marginal to many British Jews’ sense of identity. In the East End, the growth of socialism directed attention more to bread-and-butter issues, and to the looming threat of fascism, rather than to what was happening in the Middle East. The inroads made by Zionists were largely among newly suburban middle-class Jews and were related to a way of maintaining a Jewish identity against the pressures of assimilation. Although in geopolitical terms they saw their hopes realized, this did not mean that they won the argument. In 1948, when the state of Israel was created after an insurgency against British rule, only approximately 3 to 4 percent of the Jewish population in Britain opted to make Aliyah. The Board of Deputies of British Jews was still so ambivalent that as late as June of that year it averred in a letter in the Times, “We as citizens of this country can have no political relationship with the state of Israel.”

British 20th-century history tells a story of how Zionism passed from the margins to the center of Anglo-Jewish consciousness, only to return to a more uncertain position today.

But the impact of that long period of skepticism, or indifference, in Anglo-Jewish opinion still resonates. For some, a state forged through arms and realpolitik and maintained by security systems seems a far cry from the old dream of Jewish universalism, or a mission to all the gentiles. Another of Stephen Brook’s interviewees in the 1980s, historian Colin Shindler, insisted, “I firmly believe in the old-fashioned idea that Israel, meaning the Jewish people, should be a light unto the nations. It’s part of our history, our heritage, our experience.” He cited approvingly the ideas of Ahad Ha’am—himself an unhappy resident of Edwardian Britain—that Israel should be a Jewish state, in the full cultural and spiritual meaning of the word, not just a state full of Jews.

Today, in a political climate on the left that prioritizes the extraterritorial, the cultural and the identitarian, the very idea of the nation is regarded with suspicion. At a moment in which Israel versus Palestine has become a defining issue for so-called progressives, it is not surprising that some British Jews are looking to escape its grip. Perhaps it has become harder to believe that any nation-state, including a Jewish state, can be a vehicle of redemption, as a preoccupation with the universal overrides attachments to Jewish particularity.

If in the mid-20th century the struggle between Zionists and anti-Zionists was waged within communal hierarchies, it is now being fought on social media and in the alternative spaces of civil society. A new generation of egalitarians and spiritualists seek alternative forms of association, such as Grassroots Jews and Kolot Ha’Kahal, the Sephardic Egalitarian Minyan, and Kehillah (founded 2002), which features community leaders defined as Mizrahi, Latinx Jews, Asian Jews, Jews of color, non-Jewish family members, and “Jews by choice.” Such groups embody a turn away from Jewish particularity toward the more universalist notions contained in “inclusivity”—of being “a light unto nations”; even if it’s all happening in the kitchens of north London. Along with, and in some sense because of, the resurgence of anti-Zionism, post-Zionism, and non-Zionism, Zionism remains a central pillar of Anglo-British identity, though 75 years after Israel’s founding, perhaps the biggest problem with that term is the lack of clarity about what it means.