Richard Siegel and ‘The Jewish Catalog’

The lead author of the field guide to late 1960s and ’70s countercultural Judaism died last week

I did not know Richard Siegel. I met him once briefly, I think in Los Angeles, but I did not know the man. His death last week passed largely unremarked in the major centers of American Jewish life. But for anyone who lived in any one of the many margins of Judaism from the late 1960s through the early 1980s his influence was enormous and unmistakable.

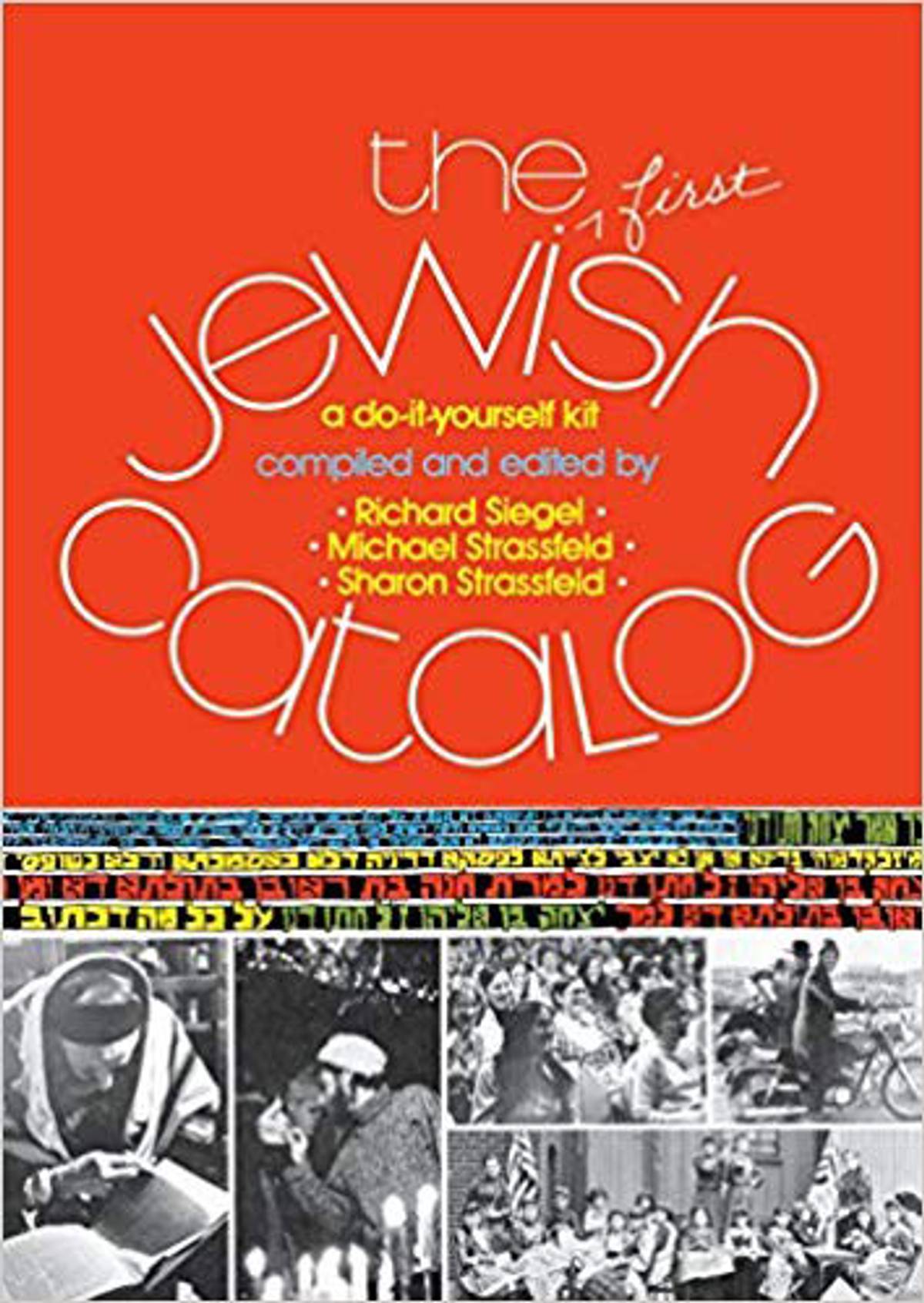

Siegel is perhaps best recognized as one of the three authors of The Jewish Catalog: A Do-It-Yourself Kit. Zalman Schachter-Shalomi once called The Catalog the Mishna of Jewish renewal. Or of countercultural Judaism more generally. The two other co-authors of the first volume, Michael Strassfeld and Sharon Strassfeld, went on to illustrious careers in the Jewish community. (Two other volumes appeared over the next half decade.) But The Catalog was born in Siegel’s mind. Eventually, Richard moved on as well, working largely in the Reform movement with a connection to Hebrew Union College, and philanthropic institutions like the National Foundation for Jewish Culture, which might seem somewhat ironic in that he co-authored the quintessential protest book against Jewish institutional life as it existed in the late 1960s and early ’70s.

The scattering of the generation to which Richard belonged is captured quite succinctly in Bob Dylan’s “Tangled up in Blue.” “All the people we used to know / They’re an illusion to me now / Some are mathematicians / Some are carpenters’ wives / Don’t know how it all got started / I don’t know what they’re doin’ with their lives.” Some Jews of that generation entered the more religious, even Haredi world, as an expression of their counterculture commitments. Some moved to Israel. Some headed to academia, some left the Jewish world altogether, and some became Jewish professionals. Richard did the latter, and injected a spirit of renewal and counterculture into the banal assimilationist mainstream of American Jewish life.

The Catalog, like many other iconic texts, had inauspicious, even humble beginnings. Siegel and a classmate at Brandeis University, George Savran, came up with the idea as part of their master’s thesis at Brandeis in the late 1960s, in those heady days when Herbert Marcuse was teaching his Frankfurt School radicalism to students such as Abbie Hoffman and Angela Davis. Jewish Studies at Brandeis, and America more generally, was just getting underway. Student protests against Vietnam had escalated, student strikes at Harvard and the takeover of Columbia University generated student activism nationwide, and the country was jolted by two assassinations in one year, 1968: Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.

Many radical Jewish newsletters circulated around college campuses; Maoists, anarchists, feminists, socialists, pacifists, Zionists, black nationalists were each voicing their protests. Woodstock and the moon landing, with the iconic photo of earth hanging in space, only a month apart in the summer of 1969, were societal and scientific bombshells. The Weather Underground, a breakaway faction of the SDS, was founded in 1970 and began to engage in violent actions to “bring the war home.” In short, society seemed to be unraveling and also exploding with creativity at the same time.

Jewish youth were deeply a part of this new revolutionary activity. Jews for Urban Justice, The Radical Zionist Alliance, The Jewish Liberation Project, The Brooklyn Bridge Coalition, Flame, Genesis II, Ramparts, The Jewish Defense League, and many other Jewish student organizations were engaging in protest activities against Vietnam, for civil rights, women’s rights, Soviet Jews, and many other causes. The Six-Day War in 1967 generated intense Jewish engagement with Israel. On the spiritual front, The House of Love and Prayer in San Francisco, the Aquarian Minyan in Berkeley, Havurat Shalom in Somerville, Massachusetts, The New York Havurah in Manhattan, Ezrat Nashim in New York, Fabrangen in Washington, D.C., and P’nai Or in Philadelphia began to challenge the nature of rabbi-led congregations and conventional synagogues and served as gathering points for radical Judaism to express itself in religious experimentation. Figures such as Shlomo Carlebach, Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, Art Green, Arthur Waskow, Paula Hyman, Max Ticktin, Aviva Cantor, Everett Gendler, Judith Plaskow, among many others served to translate the radical politics of the time into an organic Jewish frame and context.

What this nascent and somewhat diffuse group of young Jews lacked was a text that expressed their collective aspirations. This is the lacuna filled by The Jewish Catalog when it appeared in 1973. The Catalog became the book all the disparate expressions of Jewish radicalism of that period could call their own. George Savran had left the project for graduate school, and would eventually become a professor of Hebrew Bible at Indiana University and then at the Schechter Institute in Jerusalem. Siegel and the Strassfelds took the master’s thesis and made it into a countercultural manifesto modeled on Stewart Brand’s 1968 Whole Earth Catalog.

‘The Jewish Catalog’ was a ritual guide, a cookbook, a telephone directory, a source for essays on Hasidism, Zionism, halakha, and ecology, among many other things

The irony of Schachter-Shalomi calling it the Mishna of Jewish renewal is that in many ways it was the inverse of the Mishna. The Mishna was a compiled text of early rabbinic teaching that sought to exercise the authority of the rabbinic elite to dictate the “how to” of exilic Jewish life. The Catalog was more of a hodgepodge of musings, including cartoons and rudimentary graphics, depicting a Judaism for the counterculture, a Judaism without authority, a Judaism against authority. Included are directions on everything from how to bake your own matzo to tie your own tzitzit, and build a sukkah. It provided its reader with addresses of countercultural Jewish venues around the globe, including Chabad Houses, Hasidic rebbes in Jerusalem, and kosher vegetarian restaurants worldwide. It was a ritual guide, a cookbook, a telephone directory, a source for essays on Hasidism, Zionism, halakha, and ecology, among many other things. In addition, in the spirit of the then-popular Europe on 5 Dollars a Day, The Catalog was a guide for Judaism on the cheap for the anti-establishment backpacking seeker, whether they were travelling in Europe or south Brooklyn.

I first encountered The Catalog in the late ’70s when I was making my way from a macrobiotic communal house in the mountains of northern New Mexico in a tiny town called Galisteo to the ultra-Orthodox neighborhood of Mea Shearim. My fellow travelers and I found it refreshing. It was the kind of synthesis we were looking for as we attempted to move from one counterculture to another. It made Judaism recognizable, and attractive, and also radical and anti-establishment. At that time, I viewed it mostly as a way station, as I had my sights set on the Haredi world where I thought I could live the most radical life of alterity.

Many years later, after I realized the Haredi world was not what I hoped it would be, or could be, I encountered The Catalog again, this time as a scholar of Jewish mysticism and American Judaism. It was only then, with the benefit of some scholarly distance, that I realized what a precious document it was. I saw its limitations as well, its Orientalist view of Eastern European and Mizrahi Jews, its tepid critique of what would become the occupation, its Zionist romanticism, and its very gentle nod toward feminism. It was 1973 after all, and many of those kinds of critiques would be born later. The Catalog did suffer from the nostalgia that was dominant in those years but it held fast to the radicalism that brought a generation of Jews from suburban synagogues to a revived Jewish devotional life. It was a kind of Mishna, if by that we mean a guidepost to Jewish life and practice. And I knew then it would transcend its generational context.

One day recently I was sitting in New York’s Washington Square Park playing banjo. Next to me sat a young couple in their 20s. I saw they were intently reading a book together. I looked over and saw it was Ram Dass’ Be Here Now, which was published in 1971, two years before The Catalog. When I got up to leave I turned to them and said, “I see what you’re reading and I wanted to tell you I read that when I was your age and it makes me very happy to see that you are reading it now.” They smiled. I would say the same thing seeing 20-somethings reading The Catalog.

Whether he knew it or not, Siegel was composing an artifact of an era that would extend far beyond its intended audience. In the 1970s The Catalog was ubiquitous on Jewish bookshelves next to Irving Howe’s The World of Our Fathers or Shlomo Carlebach’s early LPs. In the spirit of both fun and serious protest The Catalog was closer to Allen Ginsberg than Rav Soloveitchik with the spirit of Ram Dass and the Baal Shem Tov and the storytelling of Nachman of Bratslav. The Catalog made Judaism seem fun, and spiritual, and serious, and organic, and radical (which in those days was a badge of honor). It became the text of Jewish counterculture, that which a generation pointed to and said “this!” And it’s still here.

The idea of The Jewish Catalog was perhaps akin to “Blowin’ in the Wind,” a song that took Bob Dylan about 15 minutes to compose. I am quite sure Siegel could not have imagined that almost 50 years later we would still be talking about this book. For all of the achievements of Siegel’s later career in the world of Jewish education and philanthropy, including projects together with his wife, Rabbi Laura Geller, one of the preeminent Reform Rabbis in America, now emeritus rabbi of Temple Emanuel in Beverly Hills, it seems clear to me that his place in American Jewish history will be defined by The First Jewish Catalog. He gave us a gift that defined a generation and has served as an inspiration to others. May his memory be a blessing to all who were touched by him.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Shaul Magid, a Tablet contributing editor, is the Distinguished Fellow of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College and Kogod Senior Research Fellow at The Shalom Hartman Institute of North America. His latest books are Piety and Rebellion: Essays in Hasidism and The Bible, the Talmud, and the New Testament: Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik’s Commentary to the Gospels.