The Riegner Cable, and the Knowing Failure of the West To Act During the Shoah

When and how did authentic information about the Holocaust first become known?

When and how did authentic information about the Shoah first become known? The question has been discussed in detail in my book The Terrible Secret and in Breaking the Silence (Laqueur and Richard Breitman). In the 30 years that have passed, additional information has become known. News about Hitler’s decision to destroy European Jewry and its implementation percolated out of the Nazi-occupied countries in various ways. The information came from individuals and groups including the Bund and Orthodox Jewish organizations. The central document was Gerhart Riegner’s cable sent to Washington on August 10, 1942. The general picture as presented in the 1980s need not be revised; specific issues have been clarified, others, on the contrary, are now less clear than before. My intention in the following essay is to point to some aspects that deserve further investigation.

Riegner, a native of Berlin and a lawyer by profession who was thirty years of age at the time, represented the World Jewish Congress (WJC) in Geneva. He had received the information through two intermediaries (Benno Sagalowitz, the press officer of the Swiss Jewish community, and Isidor Koppelmann, a businessman) from a German industrialist whose name he had sworn never to reveal. Riegner did in fact have to reveal it to the American diplomats in Switzerland, who made it a condition for transmitting his cable to Washington. However, these Americans were the exception. In a letter to me dated Geneva, September 21, 1984, he writes, “May I remind you, however, of our gentleman’s agreement. Somewhere you will have to say that up to this date I refused to identify the German source.” Riegner subsequently mentioned the name in his 2001 autobiography—once. He also mentioned it in a long interview with the German weekly Der Spiegel in October 2001.

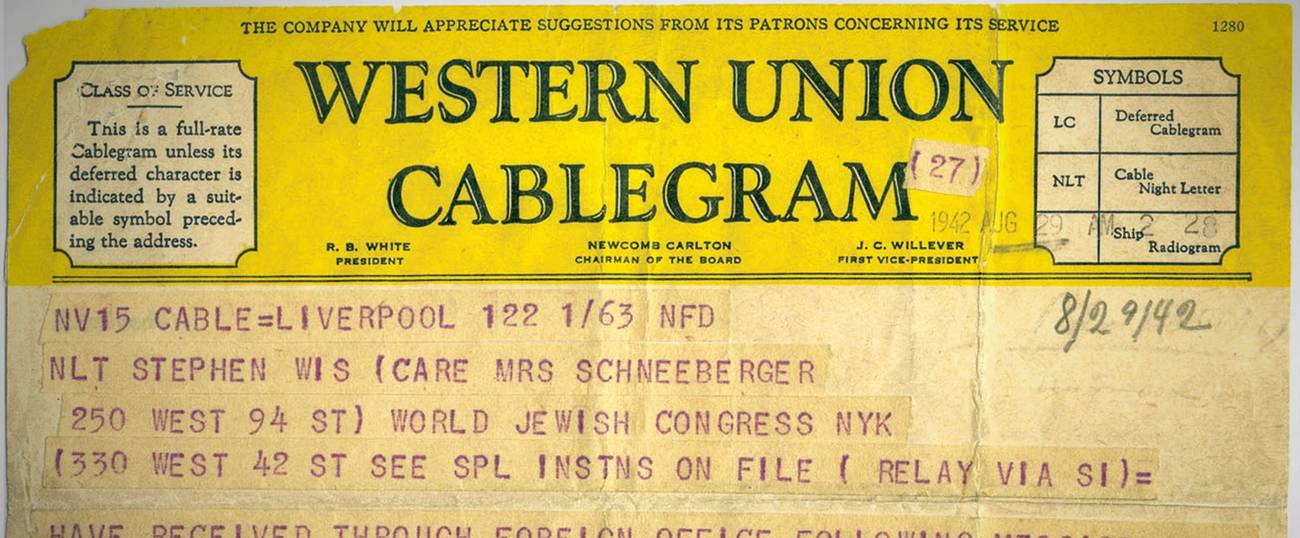

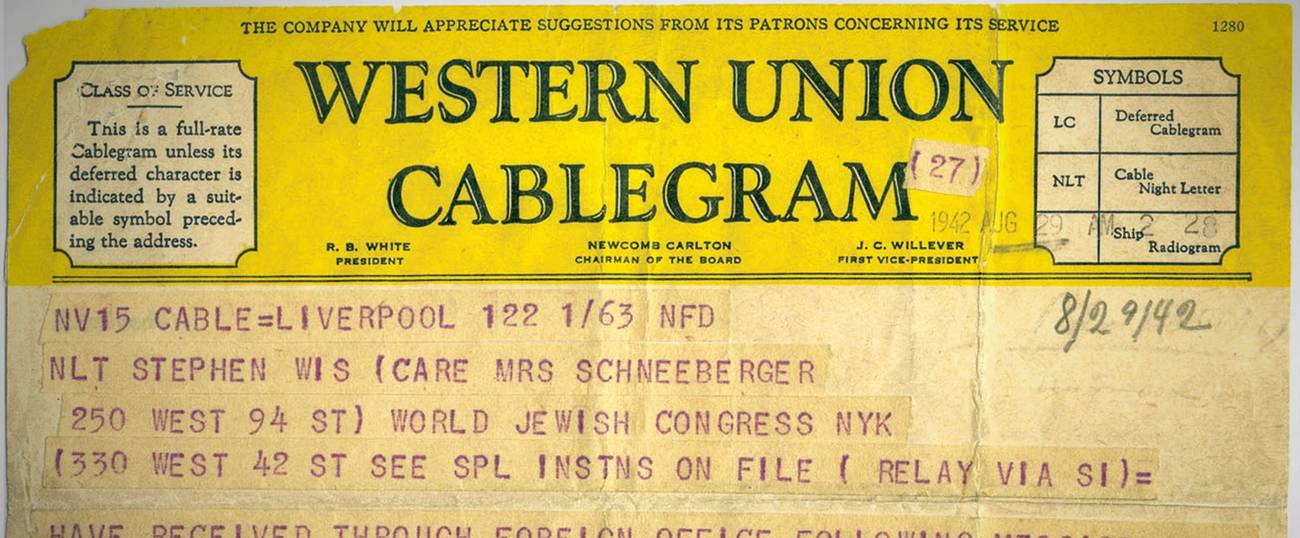

Click the image to read front of Riegner Telegram. (Courtesy of American Jewish Archives)

Breitman and I had written that there were not many interesting jobs for young émigré lawyers at the time in connection with Riegner being offered the position of representing the WJC at the League of Nations. Riegner in his letter says, “It was not that I was looking for a job. I had still a fellowship (in Geneva) which had just been renewed for another year. The real reason: I felt I could not refuse to cooperate in the fight against Hitler with the only Jewish group which tried to fight him.”

Riegner mentions in that same document that news about mass killings of Jews had reached him well before the summer of 1942. He specifically mentions reports on several thousand Jews being killed in Westpreussen (broadly speaking, the region south of Danzig), tens of thousands killed in various Polish towns, and killings by injections and in mobile gas vans. When Riegner and Lichtheim met Bernardini, the papal nuncio in mid-March 1942, they reported inter alia on eighteen thousand Jews shot in eastern Galicia and of massacres in Romania (Jassy?) and elsewhere.

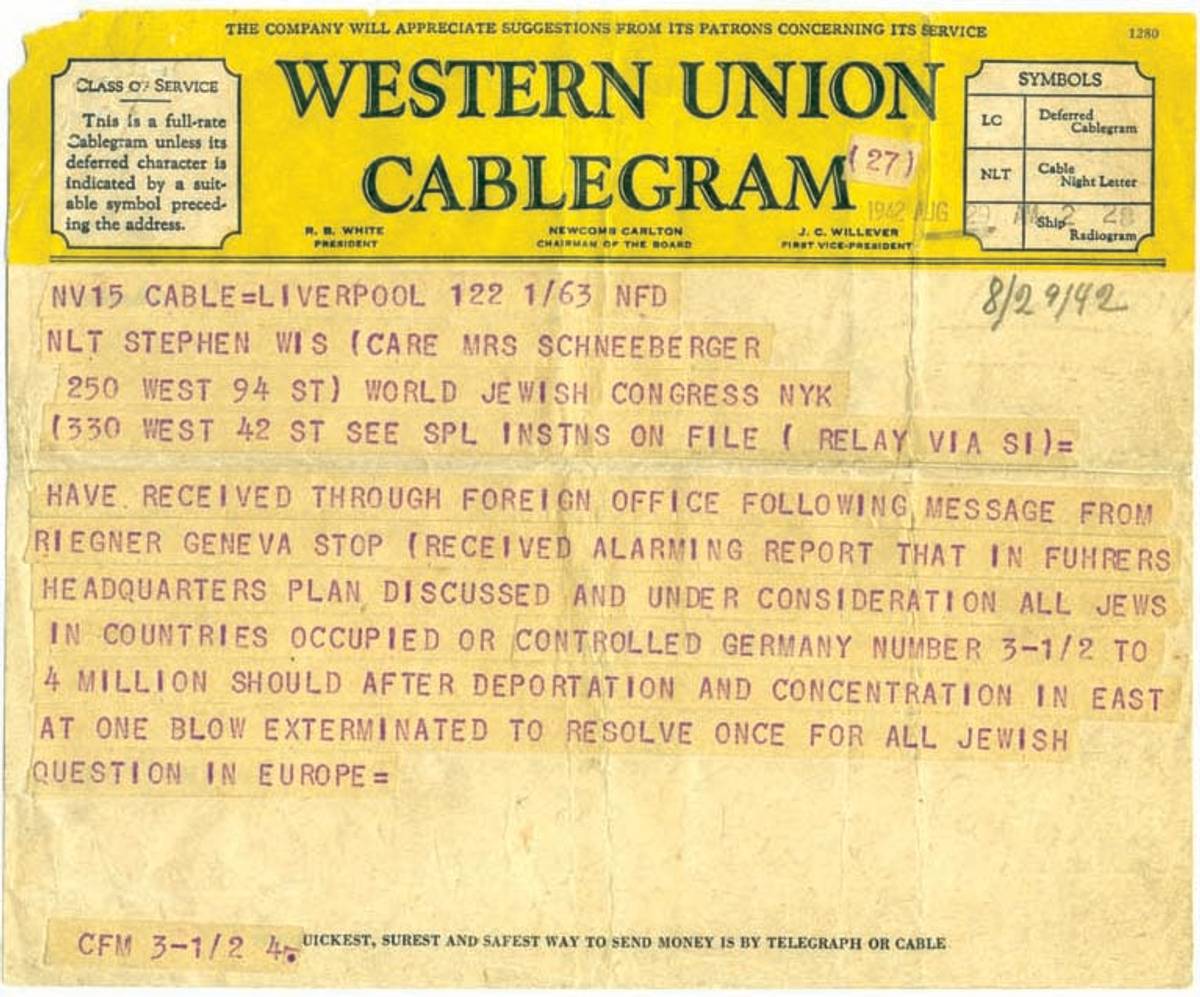

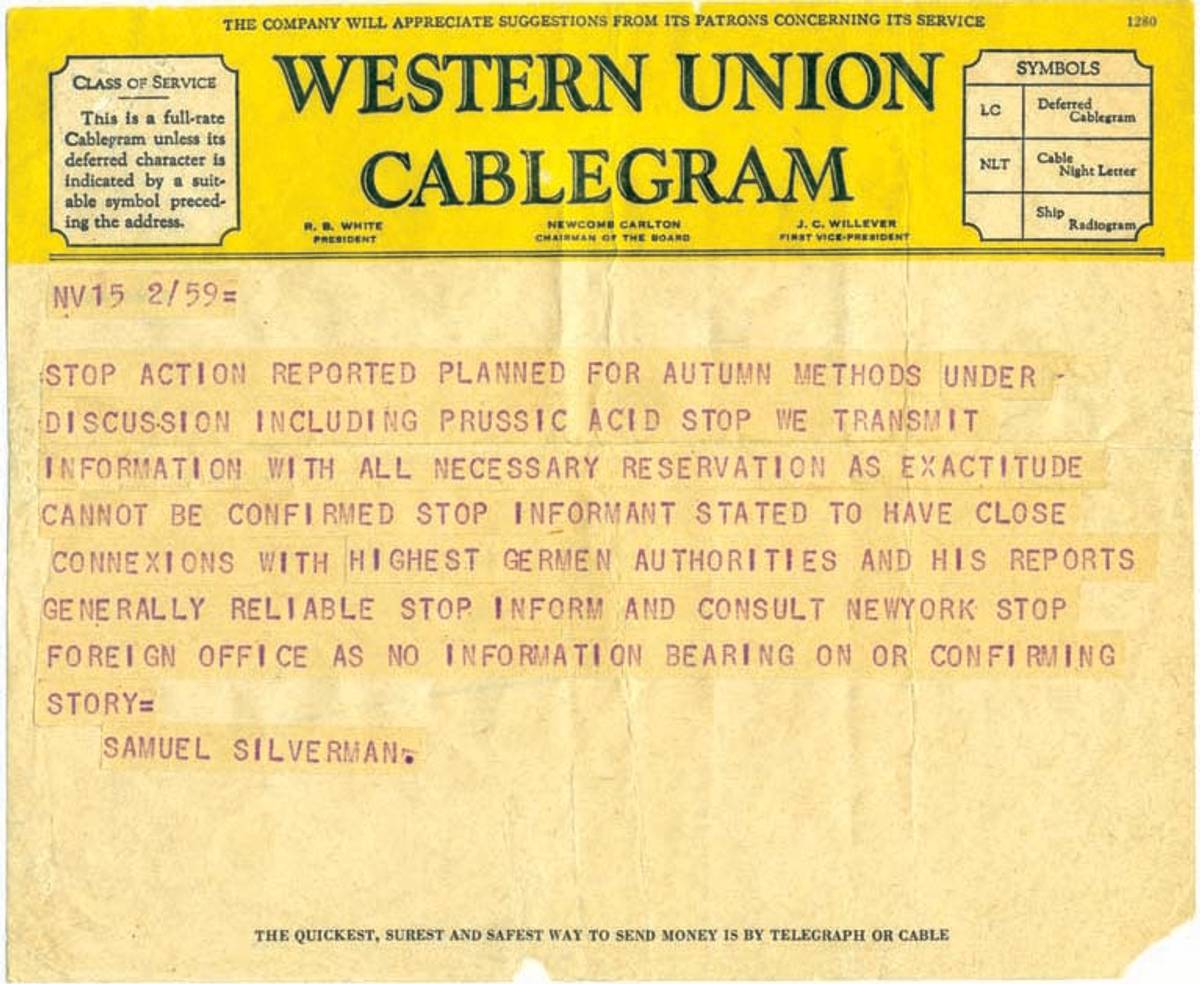

Click the image to read back of Riegner Telegram. (Courtesy of American Jewish Archives)

Riegner died in 2001 at age ninety. A few years earlier he had written his autobiography, titled Niemals Verzweifeln: Sechzig Jahre für das jüdische Volk und die Menschenrechte, which dealt with the events of summer 1942 in only a few pages, however. He continued to work for the World Jewish Congress after the war. He was active in relations with the Catholic Church, but also with the emigration of Jews from various North African countries. In view of the paucity of information published by Riegner in later years, his 1984 four-page letter to me mentioned earlier is of particular interest. Some of his corrections are indeed minor—the authors had described him as a bespectacled young man, whereas Riegner says he came to need glasses only later in life. We had written that Lewandowski, the most eminent composer of synagogue music in Germany, was Riegner’s maternal grandfather, whereas in actual fact he was the brother of his great-grandfather—but he, too, was a cantor.

Other information is of considerable historical interest. Riegner reported, for instance, that there were two versions of his cable. The longer one, which was not dispatched, contained the following:

Furthermore known here that from Paris 28,000 Jews were to be arrested and deported on 16/7 stop several thousands succeeded escape so that arrestations concerned about 14,000 stop equally several thousand Jews arrested in province especially Tours Poitiers stop at same time general terror started leading among others to plundering biggest Paris synagogue rue Victoire stop from non occupied zone Jews ten thousand foreign Jews will be delivered to Germany transports of first three thousand Jews taking place from six to ten August stop simultaneously large razzias Lyon Marseille Toulouse stop since 16/7 daily big deportations transports Dutch Jews starting from Holland stop Berlin Vienna announce equally increased deportations :stop middle July only 15,000 Jews remained Prague 33,000 whole protectorate stop 40.0000 [sic] Jews aged 65 to 85 already concentrated Theresienstadt stop from Slovakia 56,000 Jews deported already

The longer version, obviously composed hastily, is rendered here typos and all. Most of the details contained were accurate; to give but one example: The roundup of Paris Jews at Vel d’Hiv (Opération vent printanier—Operation Spring Breeze) had taken place two weeks before Riegner’s meeting with the American diplomatic representatives. The deportation of Jews from Westerbork in Holland began in June 1942. The destination of the deportations was not clarified. In Holland, the official version was that those deported were to be used for work in Germany. But since those deported included small children and others clearly incapable of participating in war work, the official version often was met with disbelief even at this early stage.

Riegner had received the information that led to his cable from Isidor Koppelmann, the Basel businessman who had been the liaison with the German industrialist Eduard Schulte, whom he had met on several occasions earlier on. While some details were inaccurate, it was essentially (in Christopher Browning’s words) an astonishingly accurate piece of wartime information. The basic difference between the Riegner cable and the various other reports was briefly this: The former maintained for the first time that there had been a decision at the highest level of the Third Reich to annihilate European Jewry. The others reported local cases of murder, deportation, and other forms of persecution.

Where did Schulte’s information originate? In all probability the informant was production manager Otto Fitzner, his number two at Giesche, the mining company of which he was the director. Fitzner was a veteran Nazi and close to Karl Hanke, the supreme Nazi leader in Silesia (Fitzner’s role is now being investigated by scholars in Germany). The issue of the killing of the Jews and Auschwitz came up at the very time of Himmler’s inspection tour in Auschwitz in July 1942. The Giesche office was very close to Oświęcim-Birkenau; its very name has been preserved to this day—Giszowiec, a suburb of Katowice. It was founded as a working-class community. The history of this community, which was meant to be patterned after British garden cities, and the history of the Giesche Corporation has recently been studied in detail by well-known Polish journalist Malgorzata Szejnert. Szejnert mentions in some detail Schulte’s initiative in summer 1942, basing her information not only on the Laqueur Breitman book, but also on documents in Warsaw archives. Her main topic, however, is the Black Garden; and while she deals with the politics intruding on industrial activities, it could be that further searches in Warsaw archives might lead to new information concerning Fitzner and Schulte.

Schulte died in Zurich in 1966 and left no written records about his activities. What we know about him is based on Breitman’s research in Washington archives and my interviews in Zurich and elsewhere with some of those who had been in contact with the industrialist at the time. Dora, Schulte’s second wife, was unwilling to discuss the activities of her husband, about which she apparently knew little. Schulte’s older son Rupprecht, a classmate and friend of mine, cooperated willingly; we met repeatedly in San Diego, where the younger Schulte had settled, and in London. The information that emerged was integrated into Breaking the Silence. The following generation—one of Schulte’s grandchildren became a professor at the University of Alaska, another an FBI agent, a third went into farming in Britain—expressed much interest in the activities of their grandfather, but they had no information that had not been revealed hitherto.

If it had not been for the Fitzner-Schulte channel, the information about the intention to exterminate European Jewry probably would have become known outside Germany within a number of months, because, as Peter Longrich and others have shown, the knowledge was widespread among the Nazi leadership and a secret so widely known was no longer a secret and could not be hidden.

What of those in the West who were in a position to know at least some of the truth and who had heard about the Riegner report? In the preparation of my work I interviewed a fair number of those who had been in intelligence during World War II or had access to information because of their position in government. I encountered a defensive attitude in many cases. George Kennan, who had been in Germany until early 1942, wanted to know exactly what was meant by the term “Holocaust.” William Hayter, a British diplomat located in New York at the time (later ambassador in Moscow and still later warden of New College Oxford) suggested that I should ask Isaiah Berlin, who also had been on a mission in New York at the time. Berlin was not amused when I related this to him. His mission to New York had been on very different lines. I interviewed Walter Eitan (Ettinghausen) in Jerusalem, an Oxford don, later the first secretary general of the Israeli foreign ministry. He had worked in Bletchley during the war, the intelligence center in which the intercepted German communications were decoded—the British having broken most of the German codes. But Eitan refused to cooperate, stressing that he had been sworn to secrecy. I pointed out that several of his former bosses had published books about their work in the meantime—but to no avail.

The old school tie helped in a few instances: Gideon Rafael (Ruffer) had been a fellow kibbutz member; during the war he headed a small institute near Haifa, which debriefed arrivals from Nazi-occupied Europe. There were a few hundred such cases, Palestinian citizens who happened to be in Germany when the war broke out and were subsequently exchanged. But the information from these sources was, as a rule, of a local character. They could not know about decisions by the Nazi leadership. In later years the mukhtar of Kibbutz Hazorea became Israeli ambassador to the Court of St. James and the United Nations.

Arthur Schlesinger, who had been in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), was one of the few who expressed amazement in later years that he and his German Jewish colleagues in the OSS had paid so little attention at the time to the fate of the Jews. So did Raymond Aron, who also was privy to that information except concerning France.

There was, I believe, no conspiracy of silence, but there was a great deal of ignorance concerning the character of Nazism and its intentions. Those looking for prophetic (and correct) estimates of the objectives of the Third Reich are better advised to consult the long valedictory cable (April 25, 1933) of Sir Horace Rumboldt, British ambassador in Berlin, than the estimates of Herbert Marcuse, Franz Neumann, Otto Kirchheimer, and other members of the Frankfurt School who had joined the OSS.

Franz Neumann wrote Behemoth at the time, the “definitive analysis of the Third Reich” in the words of C. Wright Mills, who reviewed it. It dealt with profit motives and the general economic structure of the system, the relations between industrial and banking capital, and other important issues. But it was hardly likely to shed light on the fate of the Jews or other victims of the regime, for there was no obvious connection between profit motives, the economic structure of the regime, industrial capital, and Auschwitz. According to Neumann, racism and antisemitism were substitutes for the class struggle. The Jews were extremely valuable as scapegoats for all the “evils” in Germany, and therefore, the Nazis would not embark on a policy of “total extermination of all the Jews.”

How to explain that a paleoconservative such as Rumboldt, wholly unaffected by modern social theory let alone neomarxism, was a better guide to Nazi policy, not only with regard to the Jews? Was it mainly because this was an unprecedented phenomenon? Why was Nazi Germany and its intentions widely, and for so long, misunderstood? This is yet another issue that deserves more careful consideration than it has been given so far.

Richard Lichtheim represented the Jewish Agency in Switzerland during the war and closely collaborated with Riegner. He was a highly educated man, but deeply pessimistic with regard to Nazi designs in general and the fate of the Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe in particular.

This was very much in contrast to most of the Germany experts in the foreign ministries and the intelligence services in London and Washington. When the Riegner cable reached Washington and London, these experts rejected it: Undersecretary Sumner Welles, who tended to take it a little more seriously, was in a minority. In the view of the experts, it did not make sense. If Jews were deported to the East, surely it was the Nazi intention to make them work for the war effort rather than to kill them.

In some cases open antisemitism may have been involved. Breitman and Lichtman report that Morgenthau called Breckinridge Long (a Kentucky horse breeder and assistant secretary of state) an antisemite to his face. But ignorance was probably a more important factor than antagonism toward Jews.

Furthermore, intelligence had been tasked, and among their assignments the fate of the Jews figured low. The main task was to gather information that would lead to the defeat of the enemy. But with all of this, how can one defend the order by the State Department no longer to transmit cables from abroad by private individuals or nongovernmental organizations, an instruction that clearly was intended to suppress information such as that conveyed by the Riegner cable, which had been a distraction as far as the State Department was concerned.

The British, it will be recalled, did not exercise such censorship; the Riegner cable was handed to Sidney Silverman, member of parliament, whereas Stephen Wise, who was the addressee in the United States, was never informed. It would be interesting to know exactly who gave the order to withhold information, both in the case of the Riegner cable and the general order a few months later not to transmit such information in the future.

Internal censorship in the case of some of the media has been explored. It would be unfair to single out the New York Times for almost suppressing the Riegner-Wise report (it carried a brief story in the middle of the paper); other American media did the same, except for the New York Herald Tribune, which carried it on page one. True, the owners of the New York Times were more than a little self-conscious about the Jewish ownership of the paper and acted accordingly.

Naturally, the Jewish media in Palestine acted differently. But it would be a gross exaggeration to claim that the public and the leadership of the Yishuv understood the full meaning and implications of the information from Europe and did all that could be done to save human lives.

In the transmittal of information on the Shoah, Carl Jacob Burckhardt is another personality whose important role has not been sufficiently investigated. Burckhardt hailed from an old Basel patrician family; he was a history professor who wrote a three-volume Richelieu biography. He was a friend of Hofmannsthal, Rilke, and other leading contemporary writers.

Burckhardt also served as a diplomat during the Second World War and thereafter. He met Hitler as well as many other leading Nazis, including those such as Himmler and Heydrich directly connected with the murder of European Jewry. On two occasions, Burckhardt played an important role in the present context. He was well-informed about events inside Nazi-occupied Europe, but refrained from informing his fellow members on the executive board of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). And he was strictly opposed to taking any action designed to save Jewish lives. The official excuse was that those killed by the Nazis were civilians, whereas the Red Cross was dealing only with military personnel. From a purely legalistic point of view, the argument was correct; to its honor it should be added that the Red Cross has not always acted in accordance with purely legal considerations. Burckhardt shared the social antisemitism of the upper-class Swiss; it did not prevent him from being on friendly terms with individuals of Jewish origin such as Hugo von Hofmannsthal or Leopold Baron von Adrian (an Austrian diplomat and grandson of Meyerbeer)—provided they were leading cultural or aristocratic figures. All in all, his anti-Jewish feelings were less pronounced than those of his famous ancestor (the Renaissance historian) who had written that he refused to go to the theater because of the presence of the Jewish riffraff. In a letter to his friend, Adrian Burckhardt wrote that he had known some “pure Jews with the highest moral standards.” But he still found it difficult to generate any sympathy, let alone help for the German Jews (this was written in 1933) because the German Jews had produced a degenerate Berlin culture that was deeply amoral. There had been, perhaps, some minor transgressions committed by the Nazis. But if German Jews needed help, the rich Jews could take care of them—those who arrived in their fine cars and stayed in the best hotels in Switzerland. “Fine cars,” “best hotels”—this was hardly an accurate description of the living conditions of those escaping Nazism that year.

Burckhardt, who was vice chairman of the ICRC during the war (he became chairman in 1944), did virtually nothing to help Jews in Europe. He was well informed through various contacts, but did not bring up the issue in the meetings of the ICRC executive board, even though some of its members would have supported such a move. This is on the authority of Prof. Favez, the official historian of the ICRC in wartime.

There was one interesting exception when Riegner and Lichtheim handed over their cable to Leland Harrison, the chief U.S. envoy in the Swiss capital. He insisted on confirmation by a trustworthy outside source, and since Burckhardt’s German contacts were well known, he was particularly eager to hear from him. The Jewish representatives contacted Burckhardt through an academic colleague, Prof. Paul Guggenheim, and surprisingly, while asking for the strictest secrecy, Burckhardt confirmed Schulte’s message; he had heard from a contact in the German Foreign Ministry and one in the War Ministry (and also from a German diplomat in Switzerland) that there had been a decision on the highest level “to make Nazi-occupied Europe ‘judenrein.’ ” This was the official term used at the time for the deportation and the murder of the Jews.

A few weeks later Burckhardt was contacted by Paul Squire, the American consul in Geneva, who sought his confirmation once again. But on this occasion he was noncommittal; perhaps he was afraid that he had gone too far at the earlier meeting. In any case, it was remarkable that on at least one occasion he was willing to share information with foreigners that he had refused to give to his own colleagues. One can only speculate what his motives were.

Switzerland was in a precarious situation in 1942; the Swiss could not know that Hitler had no intention of invading their country. Clearly there was no wish to provoke Nazi Germany. But it also is obvious that for whatever reason Burckhardt, the Red Cross, and some Swiss leaders went well beyond what prudence and caution demanded. Burckhardt tried to intervene in some individual cases; he tried to help Jochen Klepper, a non-Jewish German actor married to a Jewish woman. But he gave up when he was told that this was futile. Klepper, his wife, and his daughter committed suicide in 1942.

After the war the ICRC came under much criticism for its unwillingness to make public, however cautiously, the known facts about the murder of the Jews. In response, Swiss professor Jean Claude Favez was appointed by the Red Cross to write a report. Favez criticized me for inaccuracies in The Terrible Secret, which was adding insult to injury because the Red Cross archives had refused me access. But the Favez version, in turn, came under attack from the ICRC executive board—he had not sufficiently considered the pressures and threats from Nazi Germany that

Switzerland faced during the war. Eventually, more than fifty years after the event, the ICRC through the head of its archive (not the president of the International Red Cross) admitted that the activities of the organization (or rather their absence) had been less than honorable.

***

More attention should be given to the efforts to suppress this information and the lack of action; who precisely were those mainly responsible? But the question also arises—what if the information had been widely broadcast, what if those responsible for the mass murder (many of whose names were known) had been threatened with punishment as war criminals—what impact would it have had on the Nazi campaign of annihilation?

The timetable of the destruction of European Jewry has to be read side by side with the chronology of the war. During the summer of 1942, when most of the Polish Jews as well as those from the Baltic countries, Germany, and so on, were killed, the war went well from a German point of view. The great change in the fortunes of the Third Reich came only with Stalingrad and the invasion of North Africa and Italy during the winter of 1942–43. It is very unlikely that Hitler would have desisted from his campaign or that his orders would have been disobeyed by his underlings even if maximum publicity had been given to the mass murder. According to estimates, 80–85 percent of the Jews under Nazi rule already had been killed by February/March 1943. True, the Nazi leadership tried to prevent information on the murder from reaching the outside world. Thus, the police general Daluege gave an order that the figures on those killed should no longer be transmitted even in coded form. The Nazi leadership would have been annoyed if the facts of the mass murder had been widely broadcast; they would have taken stricter measures to maintain secrecy, but Auschwitz and the other death factories would not have been dismantled. After the spring of 1943, the situation changed; Mussolini was overthrown, the German Army in the east was retreating all along the front. The Battle of Kursk was lost, the Ukraine reoccupied by the Red Army; the Soviets had reached the old border with Poland and Romania. The Germans were in constant retreat in Italy; massive air attacks on German cities undermined German morale, and the belief in a final victory was rapidly vanishing. There was growing pessimism even among the military leadership.

At this very time hundreds of thousands of Eastern European Jews were still alive—the Łódź ghetto was still in existence, as was the Kovno ghetto, and half a million Hungarian Jews were still alive. If a somewhat higher priority had been given to saving these remnants, tens, perhaps hundreds of thousands of Jews could have been saved. A week before the events described here, there had been a military coup against Hitler that almost succeeded. The destruction of the Jews had been very high on the Nazi list of priorities, but from 1943 on this changed; they were fighting for their survival.

Elsewhere I have described two extreme cases of missed opportunities in which human lives could have been saved with a minimum of effort. This refers to the deportation of Jewish children from Paris on July 31, 1944, less than a month prior to the liberation of the city. More bizarre (and tragic) was the deportation of the Jews from the islands of Rhodes and Kos. Kos is very close to neutral Turkey, 2.5 miles to be precise, half of it in Turkish territorial waters. It could be reached by a good swimmer and, of course, by a rowboat, however small. Rhodes is not much farther away from the Turkish mainland. And yet a few German soldiers rounded up some 1,800 Jews (of which 160 returned) and began their deportation to Auschwitz.

For the Germans this was a logistical nightmare—Rome was in Allied hands. The Balkans were in flames, and the Allies had absolute sea and air superiority in the Mediterranean. It would have taken about one hour to reach the Turkish mainland by rowboat; it took the convoy twenty-four days to reach the death camp. No massive Allied operation would have been needed to intercept the convoy, no substantial diversion of resources from the war effort of the Allies. Two motorboats and a handful of soldiers with a few Bren guns probably could have done it. The German captain might have been persuaded to surrender without a fight. But no such attempt was made. It seems unlikely that the German garrison would have made a tremendous effort to chase the Jews of Rhodes and Kos had they disappeared overnight. The Germans knew that the days of their stay were numbered—in weeks, perhaps days. The convoy had to pass through Yugoslavia; it might not have been difficult to persuade the local partisans to disable the railway lines. Perhaps it was not all the fault of the politicians and diplomats who sabotaged rescue attempts; there was no Jewish organization or leadership.

Was it just a matter of a few isolated cases? In 1944 hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews were still alive. It has been suggested that the idea that Auschwitz could have been bombed is tantamount to Monday morning quarterbacking, that the difficulties were great, that many of the inmates of the camps would have been killed. However, the transports to Auschwitz would have stopped for a certain period of time, perhaps a long period if the attacks had been repeated.

Opinions are divided, and the technical issues involved are outside the framework of this essay. The same is true with regard to the bombing of railway lines leading to the camps, and above all, tunnels and bridges. They too could have been repaired, but it would have slowed down the transports—by days and weeks, perhaps even months, and this at a time when the Allies from East and West were advancing rapidly.

If no such attacks were made, it was not because it was deemed technically impossible, but because the fate of those concerned had very low priority. The issue of bombing quite apart, yet another aspect of this situation was seldom discussed. The victims of the deportations were not quite aware of their fate, which was certain death in the gas chambers. Had they known this, it is almost certain that at least some would have tried to hide or escape.

At the same time, many of those engaged in conducting the transports would almost certainly have done their work with less eagerness had they been warned that they might be held personally responsible—and this at a time when the outcome of the war was no longer in doubt.

Could such warnings have been issued to victims and perpetrators alike? Allied radio stations had a near monopoly in many of the regions affected. In the case of Rhodes, there were powerful Allied radio stations in Egypt, Cyprus, Palestine, and Southern Italy. Broadcasting was not the only means of issuing warnings. But no such warnings were given. No one can say how many lives would have been saved; all we know is that the attempt was not made.

***

Adapted from The Individual in History: Essays in Honor of Jehuda Reinharz edited by ChaeRan Y. Freeze, Sylvia Fuks Fried, and Eugene R. Sheppard. Copyright Brandeis University Press, © 2015. Reprinted by permission.

Walter Laqueur was head of the Institute of Contemporary History and Wiener Library in London and concurrently university professor at Georgetown University.