Ring of Truth

The Metropolitan Opera’s new Siegfried, part of its ambitious Ring cycle, exposes the greatness—and the limitations—of Wagner and his admirers

Even those of us who cannot hear Wagner without recalling the Nuremberg rallies should make an effort to understand why Wagner changed the world. The young Gustav Mahler, often cited as a composer with a Jewish sensibility, heard Wagner for the first time and wrote, “I understood that the greatest and most painful revelation had just been made to me, and that I would carry it unspoiled for the rest of my life.” No other artist changed so many lives or so drastically changed the course of the culture. Writer Roger Scruton says that Wagner’s Ring is “surely the greatest drama composed in modern times”—fatuously in my view, but his view is widely held.

“At the beginning of this century there were people called Wagnerians,” Hitler said in 1943. “Other people had no special name.” He was right. Wagner did not invent the main themes of post-Christian culture—follow your bliss, invent your own identity, do your own thing, all you need is love—but he softened us up to accept them in the intimate dimension of music. We continue to emulate him, above all in film. If we find Wagner in the original tedious, it is because the Star Wars series, the Harry Potter films, and a hundred other imitations have corrupted us with Wagner Lite.

Like Caliban, Wagner set out to people this isle with Siegfrieds. He succeeded: Luke Skywalker is the most obvious knockoff, down to the battle with and redemption of the father figure. (Wotan almost says, “Siegfried, I am your grandfather!”) Harry Potter is a younger Skywalker, except that unlike Siegfried, he doesn’t murder Dumbledore. The most popular English novel of the 20th century, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, is modeled on the Ring cycle, although Tolkien intended his epic as an antidote to Wagner rather than an imitation.

With the third installment of its new Ring cycle, the Metropolitan Opera has set a high-water mark for opera, featuring director Robert LePage’s theatrical wizardry and a strong cast. LePage devised a 45-ton mechanical set for his Ring cycle, which debuted last September with the first opera of the tetralogy, Das Rheingold. It required extra reinforcement for the Met stage, the most expensive thing the Met has ever undertaken; estimates of the cost of this cycle range up to $40 million. Much as one might wish that the Met had spent that money on Mozart and Verdi, the result is a marvel, despite occasional mechanical glitches including one in a subsequent Siegfried performance. Fortunately the big machine worked flawlessly at the Oct. 27 premiere. The set looks like a row of parallel planks, set at a 30-degree angle to the audience. As the prelude begins, the planks rotate to right angles, and we see the forest floor magnified in three-dimensional projection, with worms and insects crawling over the tree roots; it rotates again and transforms itself into the primeval forest. The Nibelung dwarf Mime takes the infant Siegfried from his dying mother Sieglinde, along with the shards of the sword Nothung. With another rotation, we see Mime’s cavern smithy next to a shimmering pool fed by a small waterfall. The morphing stage and the high-definition projections are magical.

But it is not just LePage’s shape-shifting set that lures us into the enchanted forest; it is Wagner’s music. The rhythm of a tapping anvil grows as if from primal chaos in the timpani and low winds, while a rising figure in the brass—it is the music of the Nibelung hoard—builds to a climax. Under the baton of a James Levine, the longtime Met music director now sidelined by injury, it is chilling; conductor Fabio Luisi made it sound like the Nibelungen waltz, but we will save the bad news for last.

The good news is that the Met offered the strongest cast for Siegfried in many years, headed by Jay Hunter Morris in the title role. The young heroic tenor from Texas can summon the requisite vocal brass when required but has a convincing lyrical side as well. And I cannot recall a Siegfried who looked and acted the part so well. He compares well to the leading interpreters of my lifetime: René Kollo, Siegfried Jerusalem, Jess Thomas, and James King. Opposite Morris was Deborah Voigt, one of the great dramatic sopranos of our time. The Welsh baritone Bryn Terfel sang Wotan beautifully, as he always does. Gerhard Siegel as Mime, Eric Owens as Alberich, and Patricia Bardon as Erda sang and acted wonderfully in their respective roles.

It was good enough to recall the Jewish joke about the old woman who receives a letter from her son containing horrendously awful news. “But does he write beautiful Hebrew,” she sighs. “It’s a pleasure to read.” Wagner’s news is that the West will burn, and murderous thugs like Siegfried will run wild. But the Met presented it so beautifully that it was almost a pleasure to hear.

Mime has raised Siegfried to kill the dragon Fafner, who sits upon the hoard of the Nibelungs, including on a magic ring that can make its owner master of the world. Wotan, the god of laws, had stolen the hoard to pay the giants who built his fortress, Valhalla, and the Nibelungs want it back. But Mime cannot forge the shards of Nothung. The young Siegfried will do so himself and kill Fafner as well as Mime and go on to claim as his bride the Valkyrie Brünnhilde, who lies sleeping on a mountain surrounded by magic fire.

Siegfried will overthrow Wotan with the words, “All my life an old man has stood in my way,” and replace the rule of law with the rule of unrestrained impulse, which Wagner calls love. He and Brünnhilde (who is Wotan’s daughter) shall be the redeemer and redemptrix of the world, replacing the old order of covenants with the new order of do whatever feels right. Everybody dies at the end, but they do so following their bliss.

To understand Wagner’s convulsive impact on the culture, one must hear his work in the theater. We have become accustomed to what he called Gesamtkunstwerk, or the total work of art, through film, which holds us captive and controls our visual and auditory perceptions. Wagner demands that we subject our senses to his control for many hours. (Siegfried begins at 6 p.m. and, with two intermissions, ends near midnight.)

The destruction of the covenantal world by impulsive strength, Wagner’s great theme, also involves an even subtler change in our perception of time. Western classical music subordinates individual events to a musical goal, and our perception of time depends on our progress to that goal. In the hands of the great composers, time itself can be compressed or distended for expressive reasons, but it always remains intact. In the Ring cycle, the thread of time spun by the Nordic fates, or Norns, figuratively breaks to herald the end of the old order. Wagner uses musical sleight-of-hand to evoke the illusion of a break in the continuity of time as well.

Wagner’s music usually is explained through his use of leading motifs, or Leitmotiven, short musical phrases that refer to characters or concepts. (The Wagnerheim website guides the interested listener through each use of these motifs in the cycle.) Darth Vader’s “Dum, dum-dum dumb, dum, dum-dum” and Indiana Jones’ “dee-de-dee-dee, dee-de-dee” are the idiot grandchildren of the Ring. There is something in this procedure of the handworkers’ staging of “Pyramus and Thisbe” in Midsummer Night’s Dream, in which one actor holds up brick and mortar to show that he is playing the Wall, and another holds a lantern and horns to show that he is playing the Moon.

If Wagner did nothing better than this, we would laugh off his music as a curiosity. But he was far cleverer than the musicologists. His musical aim is to subvert our sense of purpose. Part of this he accomplishes through what he calls “endless melody,” in contradistinction to classical form. The trouble is that if a melody has no end, it doesn’t have a middle, either, or any intermediate parts. “Endless melody” risks becoming an endless blah; Nietzsche wrote that the technique leads to “the complete degeneration of rhythmical feeling” and “chaos in the place of rhythm.”

But Wagner, again, is cleverer than this. He stitches together short musical numbers that point to a tonal goal, but he changes track before the goal is reached and heads in a different direction. Wagner, that is, creates expectations in the way that an audience familiar with classical form had come to expect, but artfully subverts them. To succeed, Wagner’s manipulation of musical time requires an audience that knows classical form.

A canny conductor maintains a high degree of metrical flexibility throughout, a sense of rhythmic ambiguity such that the Wagnerian change-up pitch appears as a smooth transition. Luisi, newly appointed the Met’s principal conductor, seemed uncomfortable with the score, especially in the first act. He conducted each segment with metronomic regularity, shifting abruptly into the next one; perhaps he was afraid of losing control of the orchestra and hung on to the beat all the more tenaciously. The overall effect resembled a potpourri of incomplete waltzes, polkas, foxtrots, and tarantellas more than endless melody. Luisi relaxed a bit during the second and third acts; this was the opera’s opening performance on Oct. 27, and the Italian conductor, replacing the great Wagnerian Levine, might have been nervous.

The Ring cycle’s pivotal moment comes when Siegfried shatters his grandfather’s spear, traverses the magic fire, and awakens the sleeping Brünnhilde. “The whole world exists just to ensure that two such beings may gaze on each other,” the composer wrote, and the cleverest music in the cycle is reserved for their first encounter.

Siegfried’s kiss is accompanied by a grand orchestral gesture on a B-major 7th chord, preparing a quite conventional resolution to E minor, that is, the sort of cadence from the 5th scale degree to the tonic that we hear in every piece of Western music. But Wagner has a trick up his sleeve: The E-minor chord, blown in a grand fortissimo by a steroidal brass section, isn’t a resolution at all. The top note of our E-minor chord in the brass choir resolves upward to C (pianissimo in the strings with harp accompaniment), so that we hear the E-minor triad not as a tonic chord, but as passing motion to C major. (Click here for my audio explanation with musical examples at the piano. Readers unfamiliar with musical terms might skip the explanation below and listen to the audio example instead.)

That is a piece of musical sleight-of-hand worthy of Siegfried and Roy. After first hearing it, we reinterpret what we have heard; the E-minor triad was not a point of resolution, as Wagner had tricked us into hearing, but only the preparation for something else. The real tonal goal, C major, is announced grandly in arpeggios in the harps (Wagner wanted six; the Met had four).

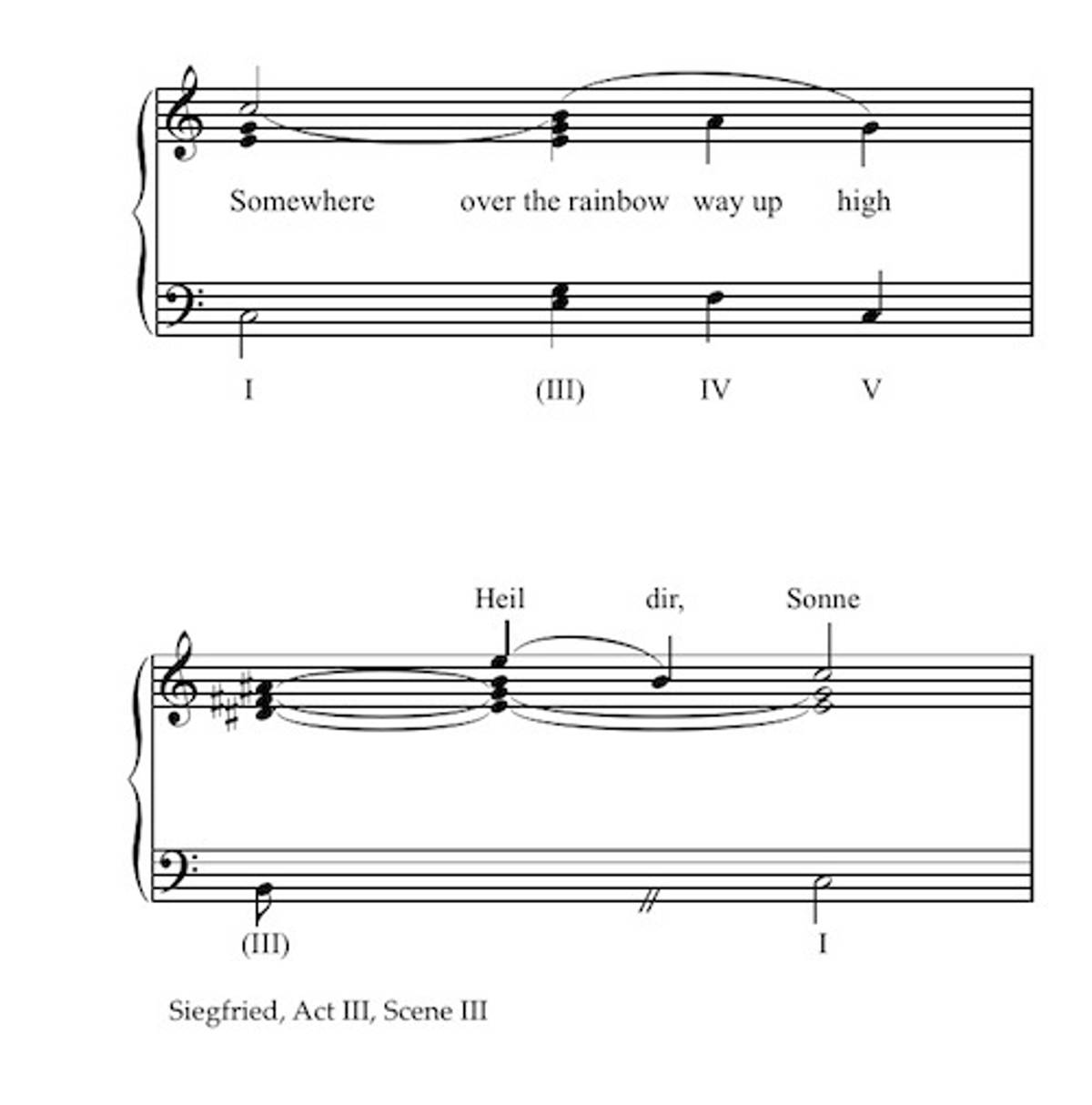

In Western music, we expect the leading tone (the 7th step of the scale) to rise to the topic (“si” rising to “do”) to achieve stability. Reversing the direction of the leading tone (with “do” falling to “si”) is a conventional gesture in popular music. We hear it in songs like “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” “Puff the Magic Dragon,” and “Both Sides Now.” It evokes nostalgia; instead of “going home” to the tonic as “si” rises to “do,” we move away from home, so to speak.

Wagner’s climatic gesture is something like “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” in reverse. We thought we had arrived at one tonal goal (E minor), but to our surprise, we find ourselves in a different place altogether. Wagner evokes in purely musical terms a sense of waking from sleep. As the leading tone rises to the tonic in its delayed resolution, we return from dream to reality.

Wagner’s grandiose gesture, laboriously prepared, twice repeated, and underscored by the full resources of his orchestra, stops time dead in its tracks: At the C-major tonality on “Sonne,” we have to stop and reinterpret where we are. Exultation in the moment replaces dedication to a goal. Of course, Wagner had to cannibalize the musical techniques of goal-oriented music in order to subvert it.

Siegfried and Brünnhilde have something in common with Siegfried and Roy: Once you know how the trick is done, it’s much less fun to watch. The better I understand Wagner’s music devices, the less I want to hear the music again, and I present this brief example in the hope that it will spoil your appetite as well.

Why, then, did the young Mahler and so many other arbiters of culture get so gooey over Wagner? The young Mahler felt his life changed; the mature Mahler said, “There is Beethoven and Richard, and after them, nobody.” W.H. Auden called Wagner “perhaps the greatest genius that ever lived.” And Wagner’s great apostle in the English-speaking world, George Bernard Shaw, said, “Most of us are so helplessly under the spell of his greatness that we can do nothing but go raving about the theater in ecstasies of deluded admiration.” Hitler had a lot of company. One can sit such people down at the piano and show that a single late Schubert sonata has more tonal originality than the whole Wagner corpus, to no avail. They will continue in their ecstasies of deluded admiration.

The reason so many clever people adore Wagner, I suspect, is the same reason that I raved about him as an antinomian adolescent: Wagner makes sensuous their desire to be free of the constraint of covenants, to give themselves to the moment rather than dedicate themselves to goals. In that sense Wagner is far more revolutionary than Marx, who read Aeschylus and Shakespeare at home: Wagner asserts the right of strength to remake the world according to caprice. Wagner delivered the cultural message of the 20th century more vividly than anyone else. That is why you should not miss the Met’s brilliant Ring cycle. But try not to enjoy it.

David P. Goldman, Tablet Magazine’s classical music critic, is the Spengler columnist for Asia Times Online, Washington Fellow of the Claremont Institute, and the author of How Civilizations Die (and Why Islam Is Dying, Too) and the new book You Will Be Assimilated: China’s Plan to Sino-Form the World.