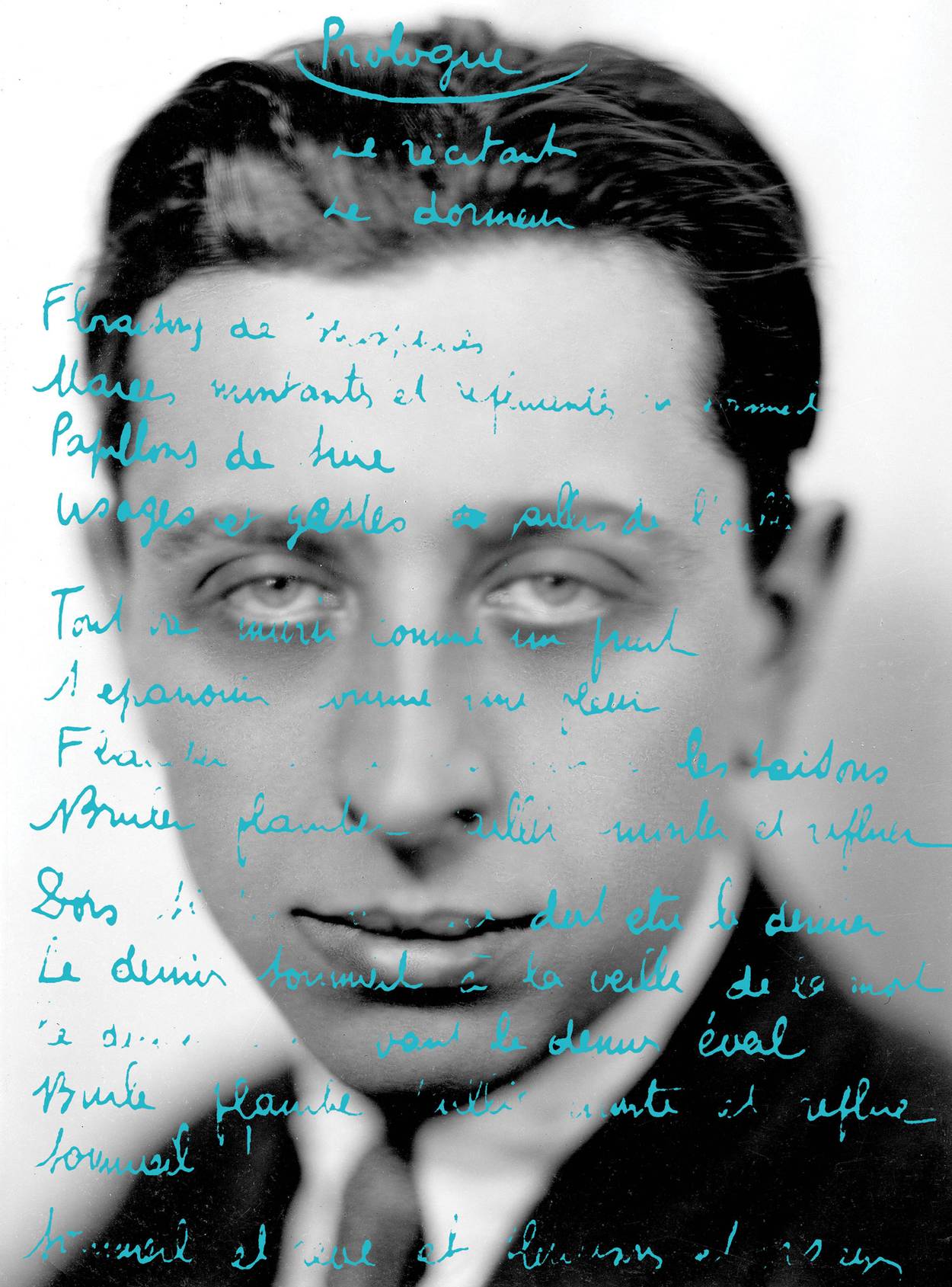

Rivers Crashing Inside

The secular surrealist Jewish poetry of Robert Desnos

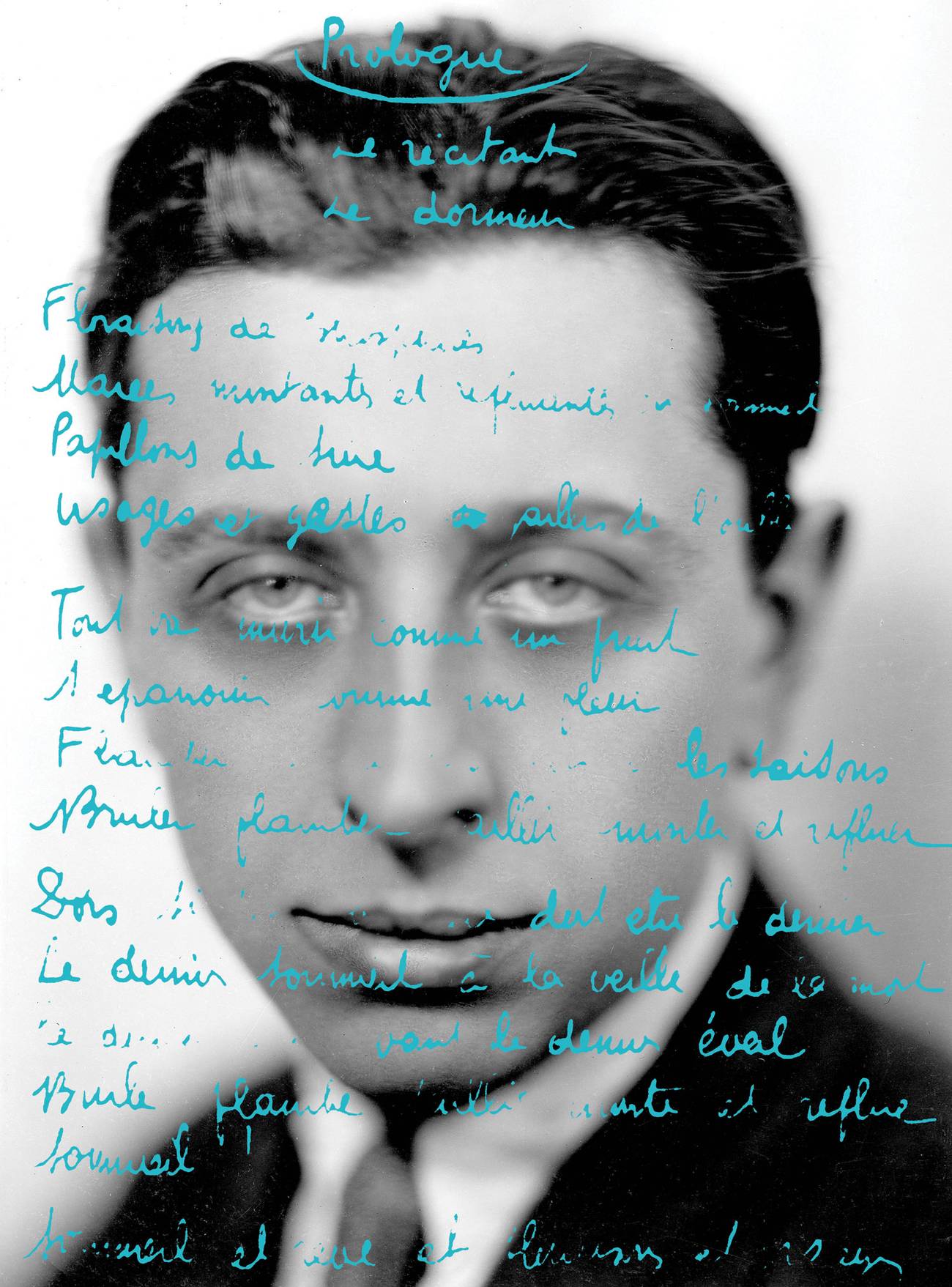

Martinie/Roger Viollet via Getty Images; Keystone-France\Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

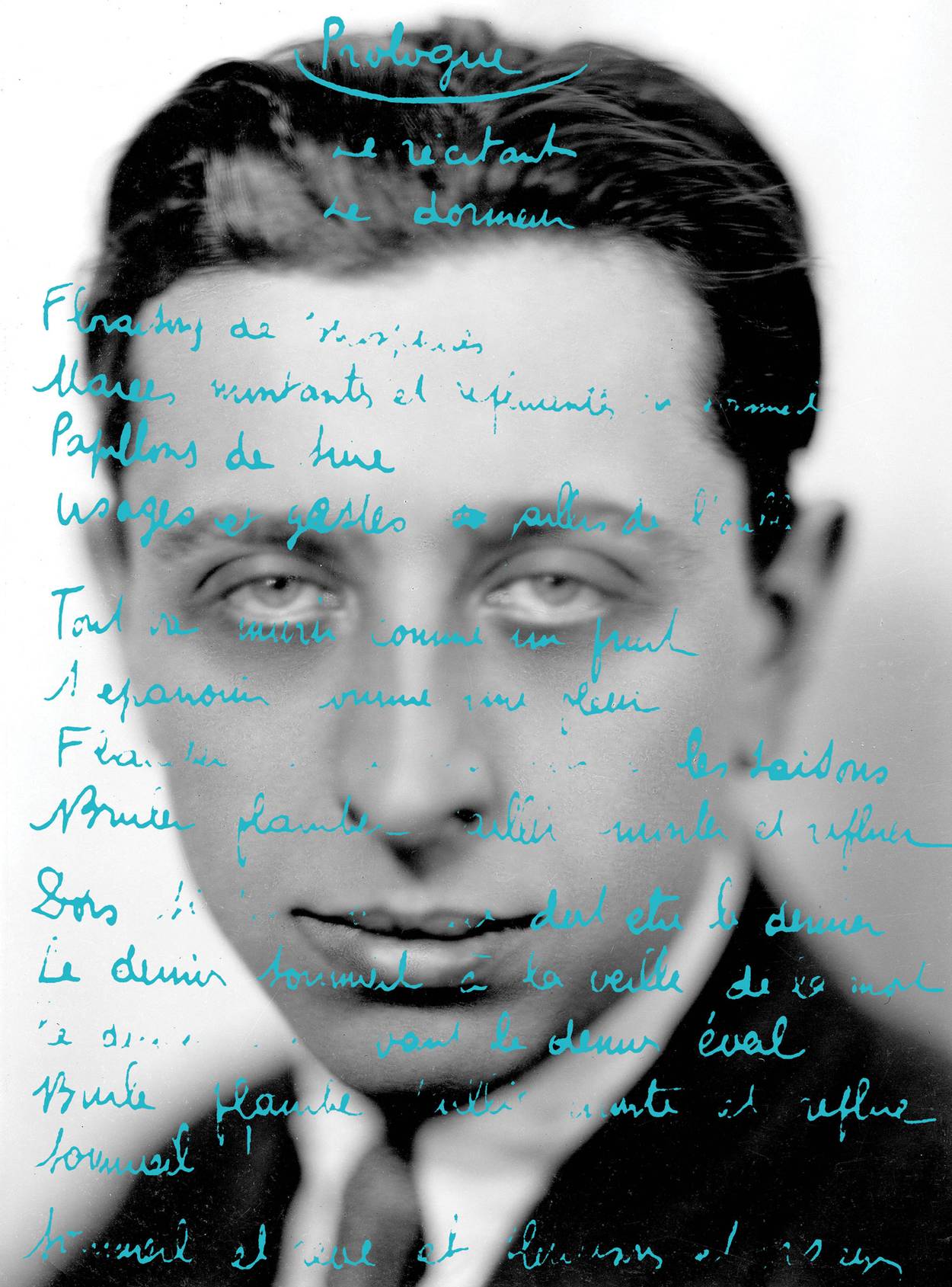

Martinie/Roger Viollet via Getty Images; Keystone-France\Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

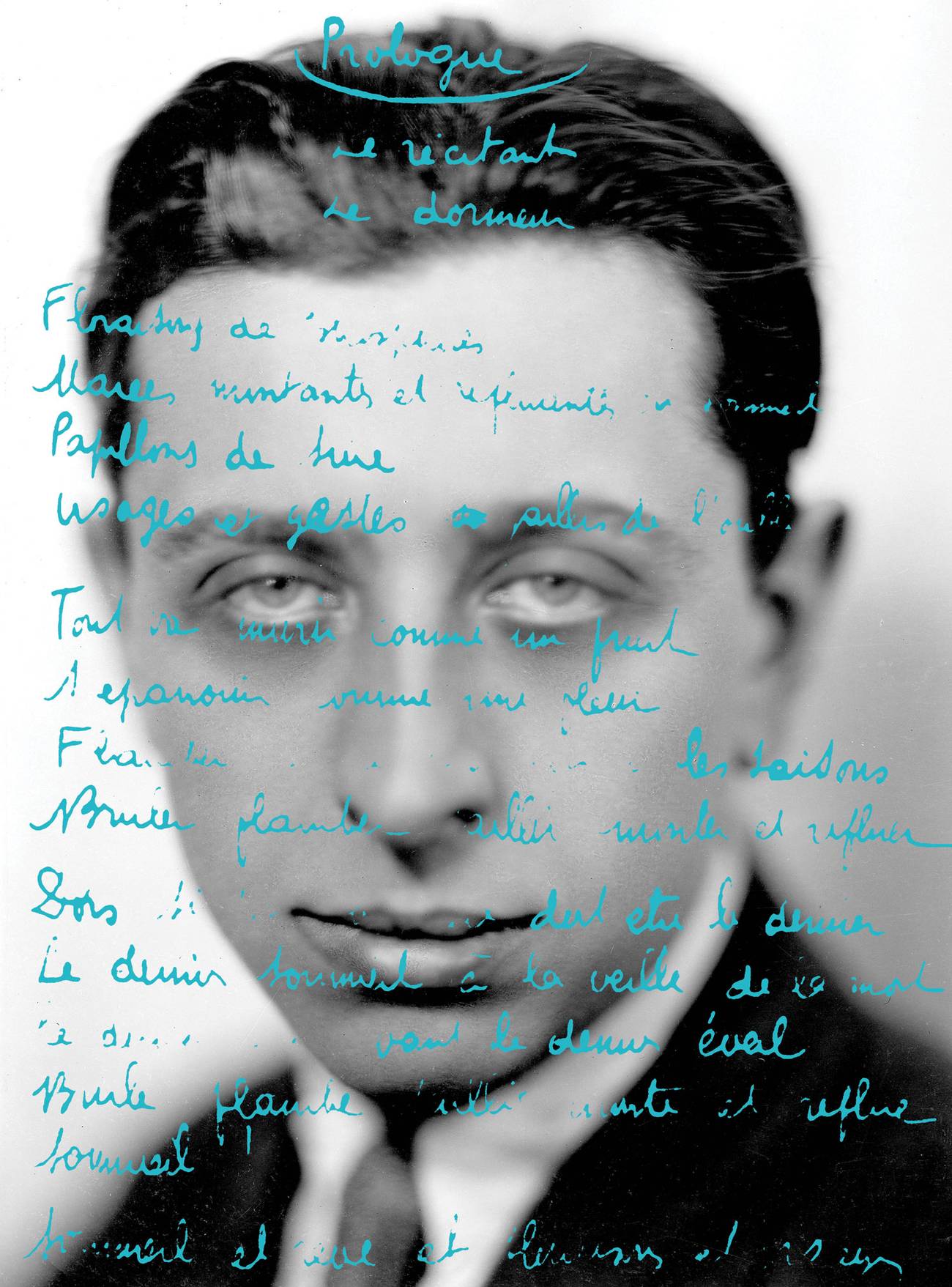

Martinie/Roger Viollet via Getty Images; Keystone-France\Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Martinie/Roger Viollet via Getty Images; Keystone-France\Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

“To really understand it, I had to try to translate it,” said New York poet Lewis Warsh to his friend and colleague David Rosenberg, referring to the work of French surrealist Robert Desnos, and in particular, Desnos’ booklong work called the “Night of Loveless Nights.” Lewis Warsh was soon to become a major voice in an influential avant-garde collective, the New York School; Rosenberg was about to become a renown poet-translator of the Hebrew Bible. Their conversation took place in the early 1970s, when both poets were still in their 20s. In retrospect, Warsh’s seemingly casual phrase encapsulated an important moment in literary history—a kind of a crossroads of literatures, languages, and movements.

It was also, looking back, an important moment in the history of the secular Jewish culture. On the 50th anniversary of the translation, and nearly a century after the poem was composed, Winter Editions has republished this volume, long out of print, with Rosenberg’s excellent afterword, offering us an occasion to revisit the poem, its translation, as well as the surrounding circumstances, the significance of which continue to reverberate.

As artistic movements, dada and surrealism presented a radical break with the tradition of European art. They were also the first major artistic movements that counted in their ranks a significant number of Jewish artists. Robert Desnos was one of them: an iconic poet—as well as, later, journalist, critic, activist, and more—he embodied the ethos of surrealism, or so the movement’s founder Andre Breton wrote in his Surrealist Manifesto: “Robert Desnos, he who, more than any of us, has perhaps got closest to the Surrealist truth … speaks Surrealist at will. His extraordinary agility in orally following his thought is worth as much to us as any number of splendid speeches which are lost, Desnos having better things to do than record them. He reads himself like an open book, and does nothing to retain the pages, which fly away in the windy wake of his life.”

Today, it is difficult to think of Desnos and the “windy wake of his life,” to read even his earliest work, without thinking about the looming fate that awaited him within the two decades of the manifesto’s publication: In 1944, after years of valiant struggle as part of the French Resistance, he was arrested by the Gestapo, deported to Auschwitz, and eventually transferred to Terezin, where he succumbed to typhus in 1945.

Back in the 1920s, however, a son of a well-to-do Jewish café owner, Desnos turned away from his family’s expectations to study literature. He was lauded by his fellow surrealists for pioneering the technique of automatic writing—the mode in which the writer attempts to give up the agency over his work to the flow of the subconscious, and remains largely unaware of the outcome all through the composition process. Automatic writing can be achieved by several means: by writing so quickly that the thoughts break their logical patterns, by writing half-asleep, or under the influence of alcohol or drugs. At surrealist gatherings, Desnos, apparently, would fall into a kind of trance, and without any external stimulations, proceeded to compose.

Not long after the publication of the “Night of Loveless Nights” in the 1930s, Desnos began his career in journalism and wrote for the radio. In a way, this poem was a culmination of Desnos’ involvement with surrealism, as well as the tail end of it. The poem, as Rosenberg writes in the afterword, “invokes every mode from epic to lyric … It’s a solo theater of the blues, an orchestration of despair raised to the level of a post-devil-may-care postwar goodbye to romantic, unrequited love.” The love, that is, for Belgian French singer Yvonne George, who died not long after the publication of the poem. Here’re the two opening stanzas:

Hideous night, putrid and glacial,

Night of disabled ghosts and rotting plants,

Incandescent night, flame and fire in the pits,

Shades of darkness without lightning, duplicity and lies.

Who sees rivers crashing inside himself?

Suicides, trespassers, sailors? Explode

Malignant tumors on the skin of passing shadows,

These eyes have already seen me, shouts resound!

This is hardly a love poem, nor is it a setting for a romantic encounter. This isn’t Paris, nor New York, nor any recognizable location. The lines, rather, belong in a nightmare, or in a dystopian cyberpunk film. The scene is vivid and terrifying, and yet somehow transcendent in its grandeur. This is apocalypse, or a mental breakdown—the kind where no rules of logic apply. “Putrid” and “glacial,” for instance, would seem to be mutually exclusive. The shift across such contradictions gives the poem a sense of a constant, propelling movement, morphing the dreamlike landscape that is nourished by fear and strangeness. The most striking image here, “disabled ghosts,” brings to mind, above all, the war: During World War I, significant masses of French soldiers returned home severely wounded and maimed.

Warsh, already at the time a masterful poet, took liberties with the text, transforming it rather than translating it literally. The opening of the second stanza, “Qui me regarde ainsi au fracas des rivières?” literally would mean something like, “Who looks at me like this in the crash of the rivers?” Instead, Warsh chooses to direct the gaze, and the crash of the rivers inward, and this difference is significant. The question posed by Desnos is spiritual: He is asking who is there to see the poet and the apocalypse unfolding around him. There is a biblical, psalmist resonance in this plea, even as it gives way to hopelessness. Warsh, however, is asking the question of what it takes to be a poet, and answers in the same breath: To be a poet is to witness the crash within. Translating a mere two and a half decades after World War II, the Holocaust, and Desnos’ tragic demise, to Warsh, the spiritual question is no longer relevant.

Having read the translation, back in the 1970s, Rosenberg published it whole in his magazine The Ant’s Forefoot, dedicating the full issue to it. He printed 200 copies and sent them around, mostly to the two poets’ artist friends, the New York school, which hailed the volume’s arrival with great enthusiasm.

In an interview over Zoom, Rosenberg spoke to me from his home in Miami, recalling the conversation with Warsh, and the urge to translate the poem. “It wasn’t something he was doing programmatically in any way,” Rosenberg recalled, adding: “For us, expanding or remaking of conscious awareness, aesthetically—it was actually more politically revolutionary than politics.” In other words, Rosenberg explained, the work was completed in a way that contrasted the reigning academic approach to translation: For Warsh, this wasn’t a job, or even a scholarly exploration, but a rather personal matter, an attempt to understand his lineage, and the trajectory of the poetic tradition he was inheriting, while, at the same time, reworking it.

Reflecting on Desnos’ work, Rosenberg pointed out: “It’s clear that his Jewishness did not affect him very much as a French poet, and that was true for me, and true for Lewis. We hardly thought about being Jewish at all … The Holocaust was such a defining moment in literary consciousness, in artistic consciousness, that we were almost in a new age—that is, also to say that we were rather naive. We did not know a lot of history, real history. We were bound up in artistic history.”

The two poets would eventually grow to discern the political underpinnings of the relationship between surrealist aesthetics and Jewishness of some of its members. What distinguished dada and surrealism from previous literary movements was the cosmopolitanism of the artists: So much art that came before was rooted in the national traditions while, here, the work transcended the literary, and literal, borders. It wasn’t concerned with nationality or ethnicity or religious background: It was all about the “rivers crashing inside,” as the poem had it. This impulse is what eventually led the Nazi movement to coin the term “Degenerate Art” to describe the avant-garde expression that dada and surrealism exemplified. It is easy to see how threatening the new art was to totalitarian, nationalist regimes. This is what Hannah Arendt meant when she wrote, in The Origins of Totalitarianism, that “Intellectual, spiritual, and artistic initiative is ... dangerous to totalitarianism ... more dangerous than mere political opposition.”

Desnos may not have consciously set out to write a political poem, or a poem, associated, in any explicit way, with his ethnic roots: The dream of an overhaul of European consciousness was not unique to Jewish poets. Yet, it makes sense that as a cosmopolitan and multilingual artist, yearning to break away from his marginal, minority status, Desnos craved to transcend ossified categories for the sake of a fresh start. “We study other languages, the signs & mirrors, so that we can inhabit the conversations of people we’ve never met,” wrote Warsh, years later, in his poem “Omen.” This is the conversation Warsh tuned into, even as he also worked hard on the poem’s long and exquisite ride that takes its reader from post-apocalyptic landscapes into eerie love declarations, such as:

I give everything to you, down to the heart of the ghosts,

Submit it to my fatal and delicate torment

Leave in order to disappear in two lines of a book

Without having invoked the evening of lovers.

What is the heart of a ghost? It would seem that the beating heart is the very thing that the ghosts are missing. If ghosts are most vivid and impossible memories that continue haunting us for a long time, the heart of the ghost is perhaps our own heart of hearts, treasured and traumatic memories that make up who we are. Nothing is more personal than that. However surreal and strange, this is an incredibly tender, personal thing to say to a lover. In the original French, it seems that such ghosts will be disappearing into the lines of a book, as if dissolving into the poem; in Warsh’s rendition, grammatically, what is about to disappear is, well, “everything.”

Perhaps it is unfair to read Desnos through the lens of his fate. Yet, it is also true that poetry was always bound up with prophecy, with access to language that was charged enough with meaning to reveal more than its intention. What else can one make of lines like these, that ring with tragedy and hope both:

Escape from the water, the prisons, the gallows,

Goodbye, as one who bruises the morning I depart.

There are no places which have the distance

Of the words: I loved you! murmured from far away.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of Cosmic Diaspora (2020), The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). He has also released two jazz-klezmer-poetry records: Purple Tentacles of Thought and Desire (2020, with Cosmic Diaspora Trio), and Hermeneutic Stomp (2013).