The Century-Old Science Fiction Story That Predicted Our Current Cultural Malaise

Max Beerbohm’s ‘Enoch Soames’ is an ode to those perennially forgotten eccentrics who make civilization possible, and a warning about what happens when they disappear

Sometimes, when the particular moment in time into which you happened to have been born seems dumb beyond relief, time travel is the only option. Watching what we understand to be our civilization tumbling into a bottomless pit of despair, we may be forgiven for wondering if this is just a passing phase and if the future, bless it, is likely to be any better.

The answer, of course, is no.

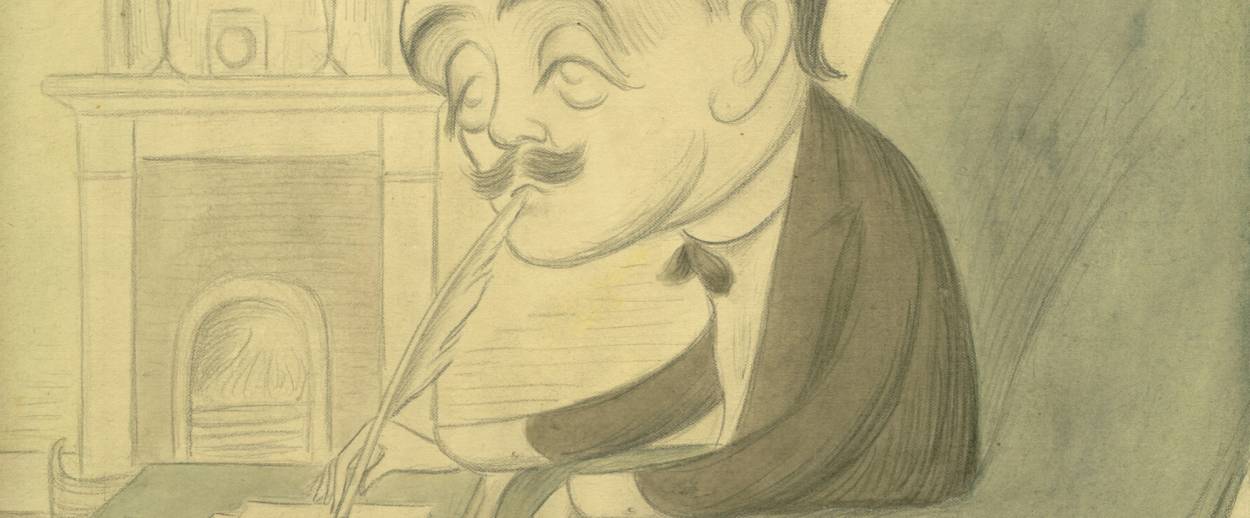

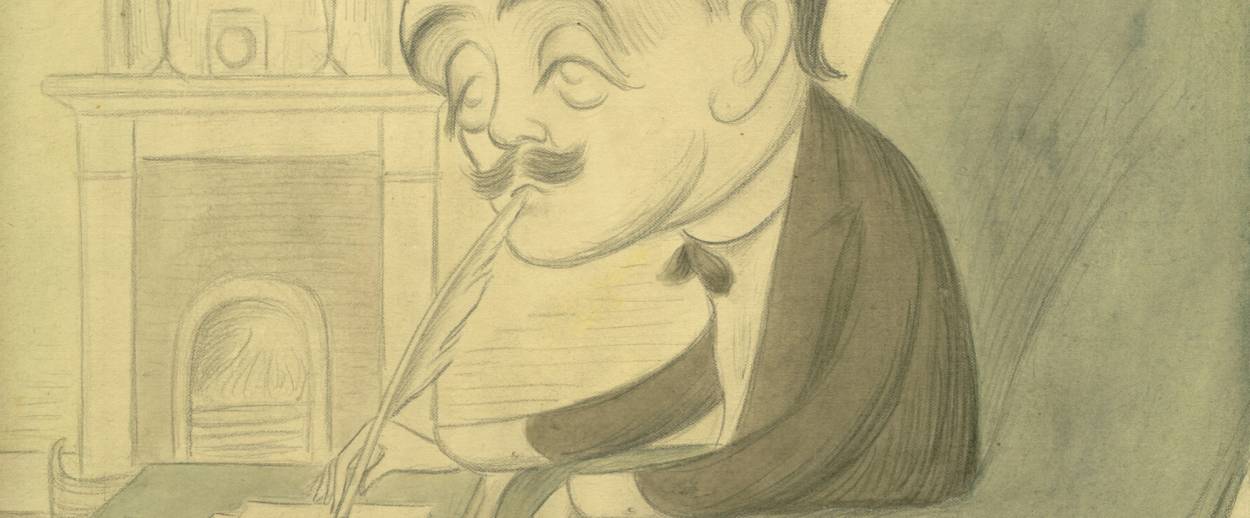

This is the lesson delivered one hundred years ago by Max Beerbohm—caricaturist, humorist, sharp dresser, repressed homosexual, closeted Jew—in a short story called “Enoch Soames.” Its protagonist, the titular Enoch, is a miserable wretch: The only thing more inelegant than his misshapen waterproof black cape is his prose, which, to the modern reader, may evoke the assaults against elegance perpetrated daily at any of our college campuses. Soames, tragically, fancies himself one of the greats, a mind so towering as to gaze down on Shelley and find him wanting. He totters about London, always at the side of whatever smart set happens to be congregating at galleries or cafés or parties, attempting to assert some prominence.

The story’s narrator, Beerbohm himself, observes Soames with awe at first, then with a pity that deepens as Beerbohm’s own literary success grows. And just when you think you’re reading a touching little dramatic slice of fin de siècle bohemian London, Beerbohm turns the tables. Quite literally: As Soames and the narrator are supping in a small and cheap restaurant, the failed writer moans that he would give anything to thrust himself one hundred years into the future, so that he may learn if posterity was any kinder to his reputation than the present day. A gentleman dining nearby eavesdrops on their conversation, pushes his table over, and introduces himself as the Devil. He will send Soames precisely a century into the unknown, he says, in exchange for the usual price mortals pay when they strike a deal with the Morning Star.

Soames agrees—could he really have done otherwise?—and is awarded five hours in the year 1997. The narrator tries to dissuade him, but the promise of seeing his own suffering vindicated by eternal literary glory is too much for Soames to resist. He agrees to the Devil’s terms, and, in a flash, disappears.

When he returns, he is—could it have been any different?—a profoundly broken man. Having rushed to the British Library to look himself up in its catalogue, he finds but one mention of Soames, Enoch. It’s in a book titled English Literature 1890-1990. Or, rather, Inglish Littracher 1890-1990, as the English-speaking peoples seem to communicate now in a phonetically spelled language reduced to its most elemental structures. Looking for himself in that definitive anthology, Soames finds only the following sobering passage and learns that he would henceforth be remembered not as a living human being but only as a fictional character created by his friend Beerbohm:

a riter ov th time, naimed Max Beerbohm, hoo woz stil alive in th twentith senchri, rote a stauri in wich e pautraid an immajnari karrakter kauld “Enoch Soames”−−a thurd−rait poit hoo beleevz imself a grate jeneus an maix a bargin with th Devvl in auder ter no wot posterriti thinx ov im! It iz a sumwot labud sattire, but not without vallu az showing hou seriusli the yung men ov th aiteen−ninetiz took themselvz. Nou that th littreri profeshn haz bin auganized az a departmnt of publik servis, our riters hav found their levvl an hav lernt ter doo their duti without thort ov th morro. “Th laibrer iz werthi ov hiz hire” an that iz aul. Thank hevvn we hav no Enoch Soameses amung us to−dai!

Beerbohm anxiously walks the streets of London, waiting for Soames to reappear. When the time-traveler finally materializes back in the same cheap restaurant, Beerbohm begs him to run away. Soames, he suggests with the master’s sly touch, should abscond to the south of France; even the Devil himself wouldn’t look for him there. But Soames refuses. Somberly, he sits and waits for Satan to show up and claim his due. Eventually, the Horned One pops by and grabs his wretched prey. As Soames is being rushed past the door and on to eternal damnation, he turns to his friend with one parting wish: “Try,” he begs, “to make them know that I did exist!”

What to make of this tragic ending? Beerbohm—ever the humorist, ever the gentleman—ends the story by noting that he’d seen the Devil once again a short while thereafter, and intended to speak to him harshly about how he’d mistreated poor Soames, but, out of habit, merely doffed his hat and walked on by. We readers, however, can hardly do the same thing. Soames haunts us. Unlike Beerbohm the narrator and his fancy friends, Soames refuses to entertain thoughts of escape because art, to him, is no pastime or party trick but a sacrament. We recall, as we see him stoically awaiting his demise, that this is the writer who’d refused to give his collection of poems a title, fearing that a fancy name would distract readers from the difficult truths therein. Like his deal with the devil, it’s a ridiculous way to act, but also one that suggests real commitment to something greater than one’s own career.

That thing, of course, is culture itself, and what truly terrifies Soames about the future may be not only his own nonexistence therein but also the knowledge that our shared artistic pursuits have all collapsed into a heap of phonetically spelled, government-run nonsense. This, for Soames, is hell, and having already been there, he hardly cares about the devil and his dark destination. Flames and pitchforks are luxuries compared to a future in which the fire of creation has died, all art is trivial, and most people dumb.

Which, naturally, brings us back to our particular moment in time, as every good time-traveling story ought to do. What ails us? If we listen to Soames—a grim existentialist prophet and a literary figure, like Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener, who endures because he argues that resistance is as cleansing as it is futile—we know that our problems aren’t just the occasional bloated billionaire demeaning the foundations of our democracy or the frequent drivel on TV we feel compelled to watch, recap, and parse. Our loss is greater: We indeed have no more Enoch Soameses among us today, which means no more monks willing to spend their days in the reading room of the British Museum, studying the foundations of the past while toiling to make meaningful contributions in the present, no matter how silly and self-important they may seem in the process.

Every human pursuit worth a damn depends on these men, on these forgotten Enochs. Journalism needs them to be diligent enough to tap every source and check every statement. Criticism calls on them to embody ancient aesthetic arguments and relive them anew. Art commands them to inflame their hearts and minds until, feverish, they radiate truth and beauty. Government expects them to toil in perpetuity, forever standing just outside the circles of men and women who matter. These Enochs are forever forgotten, but never insignificant; they’re the servants who make culture possible.

And for the past one hundred years, at the very least, they’ve been disappearing at an alarming rate. Today, no one would take the same trouble as Soames and wrestle with Shelley; instead, we share our own solipsistic thoughts and tastes and passions on Snapchat and Tumblr and Instagram. We are always peering at the present, seldom at the past and almost never at the future. Soames grew invisible as he strove to serve culture at large; we, on the other hand, became permanently visible by obliterating it. Traditions, institutions, and the thankless labor required to uphold them struck us as ludicrous as seeing a visitor from the nineteenth century popping by for a spell in the twenty-first. We’d rather doff our hats and just walk on by to the next engagement, the next distraction, the next fun. But we need the Enochs; without them we’re just the hoard, swaying along to its own desires. Thank God, then, we still have one Soames, even if he’s just an immajnari karrakter.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.