The Second-best Photographer

A family portrait becomes an act of betrayal

In 1952, my older sister, Bailey, won a scholarship to the University of Michigan. Though only a three-hour drive, Ann Arbor could hardly have felt farther from our working-class neighborhood in Grand Rapids. We lived near furniture factories, where many of our Polish neighbors worked. We liked our neighbors but didn’t necessarily trust them. European memories persisted. We were their Jews; they were our goyim. When I walked to school, I would wave to Pani, the old woman who swept her porch every morning. She waved back and called me, “zhidu,” little Jew.

Bailey moved into the Martha Cook dormitory, which she told us was for “serious girls.” Long distance phone calls were expensive, but we called her every Sunday night. Bailey’s roommate was from Denver, and she met lots of people from Chicago and Detroit. She had learned to type legal documents and talked of becoming a lawyer. “It’s not that hard,” she said. I was in sixth grade, and when Bailey returned home from Ann Arbor for the summer, I tried to read the books she had brought home, books on policy issues and the French Revolution. In only one year, Bailey had become sophisticated. The rest of us would need to catch up.

One morning that summer, Bailey took me and our sister, Matkey, aside and revealed her plan: We were going to hire a photographer to take portraits of the three of us. The photos would be a 25th anniversary gift for our parents.

I thought it was a good idea and assumed Mr. Sandler would take the photos. Whenever our family celebrated a special occasion, Mr. Sandler would arrive with his camera. I’d guess it was a 35 millimeter, but, at the time, I thought of it as a serious professional instrument, like a microscope. He even had a special lens for closeups. When it was time to take the photos, Mr. Sandler told us where to stand and raised his camera before his long pale face.

I loved Mr. Sandler’s visits. He smoked a pipe and had an accent—not the Polish and Yiddish accents I was accustomed to but an Irish accent—a pipe-smoking Irish Jew! He was a friend to us all, a friend who told us stories about Dublin and its Jewish mayor, a friend who wouldn’t accept any payment other than some of my mother’s baked goods. Out of his own initiative, he’d shown up to my elementary school graduation to photograph me. Bailey was close with his daughter Maureen. Of course, we’d ask Mr. Sandler to take the photographs for my parents’ anniversary. How could we ask anyone else?

Bailey looked at Matkey and me: “Van Dyke will take the photos,” she said.

That Bailey knew of a second option for a photographer was not, in itself, surprising. When it came to professionals, our family tended to have two of each: a best and a second best.

Our best doctor, Dr. Schnor, was responsible for major organs—in particular, the gallbladders that plagued my mother and grandmother. He had a medical degree from Vienna and an expertise in thyroid disorders. He spoke English, German, and Polish, but not Yiddish, so I would accompany my grandmother to his office as her translator.

Dr. Schnor took no appointments. If you wanted to see the tall slender Austrian who kept gray stubble on his chin and prescribed a warm bath for every ailment, you had to wait. I would sit in a cracked leather chair in his crowded waiting room trying not to stare at the old women, goiters bobbing beneath their chins like small animals. When he was finished examining my grandmother, Dr. Schnor put her pills into a small paper envelope and licked it shut.

After the Korean War, a new doctor came to Grand Rapids, our first Jewish doctor. Dr. Farber immediately became our second-best doctor. We knew that he wasn’t as good as Dr. Schnor, but because he was Jewish, we presented the young physician with our less critical ailments—the sore throats and ear infections and the occasional bout of constipation.

Both doctors made house calls. Dr. Schnor’s visits were brusque and direct. He accepted payment but no refreshment beyond a glass of ginger ale. With Dr. Farber, it was never just a medical visit. He arrived late in the day, after office hours. When he had the time, he stayed for a meal. That second-best doctor put away gefilte fish, latkes, chicken—my mother and grandmother served him as if he was our guest at a Seder. By the time he finished and patted his lips with the corner of a cloth napkin, we had almost forgotten the ailment.

We also had best and second-best dentists: Dr. Deleifide, a Protestant tooth extractor, and Dr. Feldman, a modest man whom we visited when we didn’t really need a dentist. We had two carpenters—both called “Bob” by my grandmother—and two house painters, Ed, who spoke Polish but swore in English, and Everett Cooley, who couldn’t paint well but came from Boston—to us it was like coming over on the Mayflower.

We required two of each professional, I now see, because there were two of each of us: a shtetl Jew and an American. We loved America, but we praised her best in Yiddish, our second-best language.

Bailey understood that Matkey and I needed an explanation for why Mr. Sandler would not be taking our photographs. The next morning, she walked us downtown to a photography studio. Through the plate glass window, we looked at photos of handsome people standing or lounging near Michigan elm trees. At the bottom of each photo there was the same slanted signature, “Van Dyke.”

“He’s an artist,” Bailey said. She directed our gaze to one of the framed photos. I saw five bodyless faces of children—each one shining and surrounded by a glowing white halo. “It’s called a montage.”

I asked why Mr. Sandler couldn’t take our pictures. It wasn’t just that I liked Mr. Sandler, our family valued loyalty. When Ted Johnson lost the lease on his Standard gas station and opened a Texaco station a 20-minute ride across town, my father drove the distance to buy gas from our friend. When a new A&P supermarket opened on Stocking Street, we didn’t stop going to Walt’s Red Rooster on Front Street or the IGA store a block from our house.

“Mr. Sandler can’t do a montage,” Bailey said, still gazing at those beautiful people in the window of the Van Dyke studio. “For their 25th anniversary, they deserve an artist.”

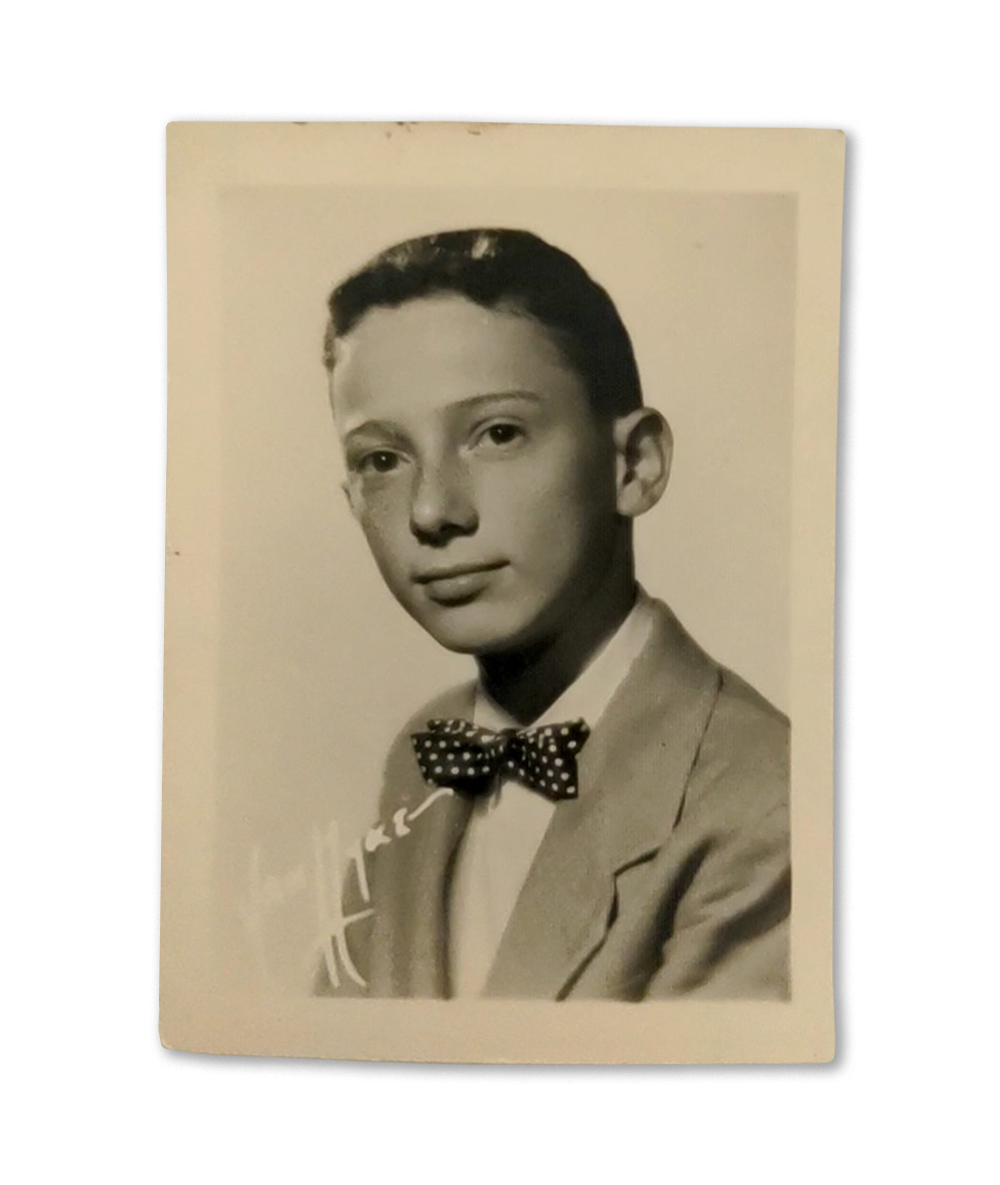

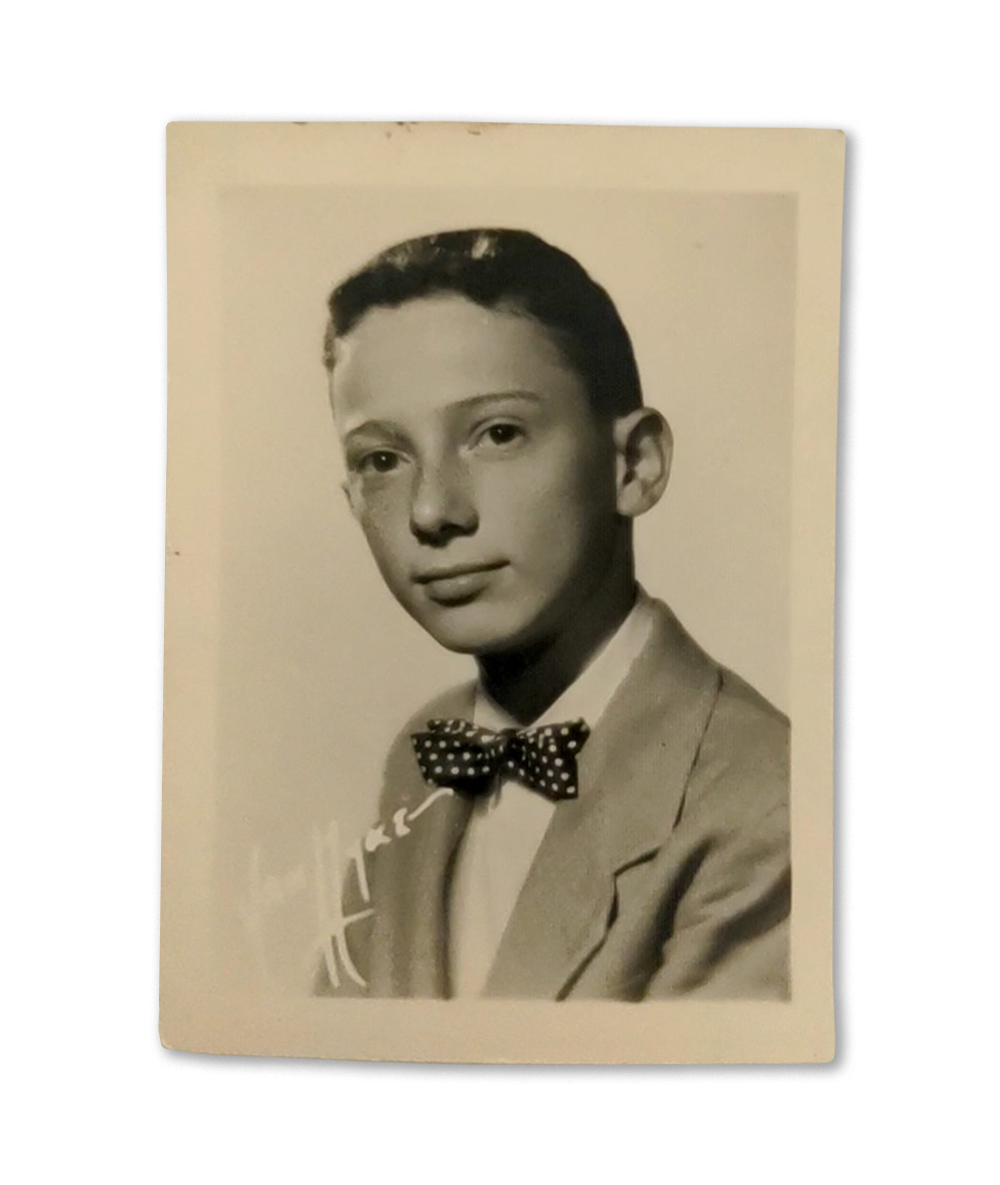

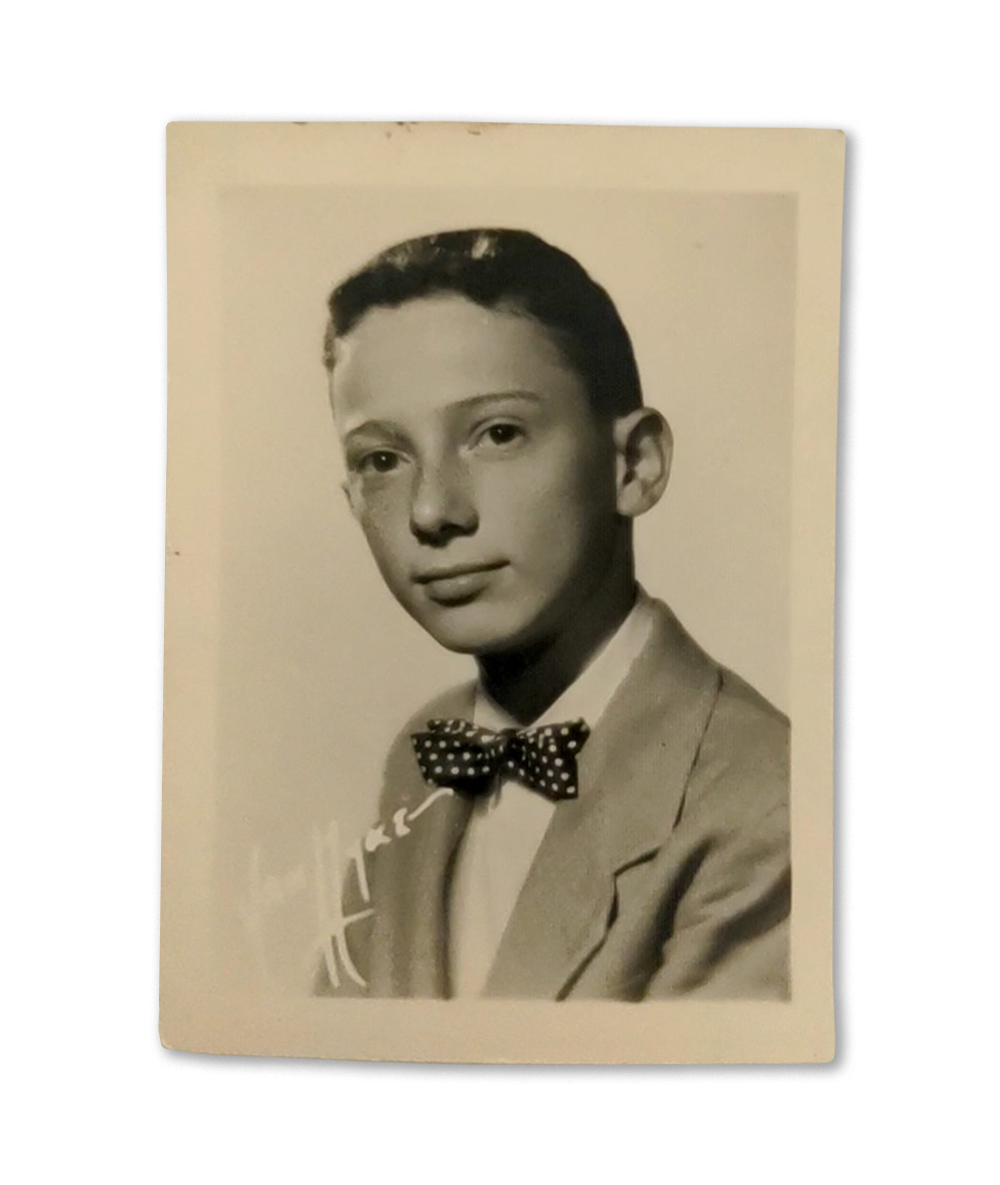

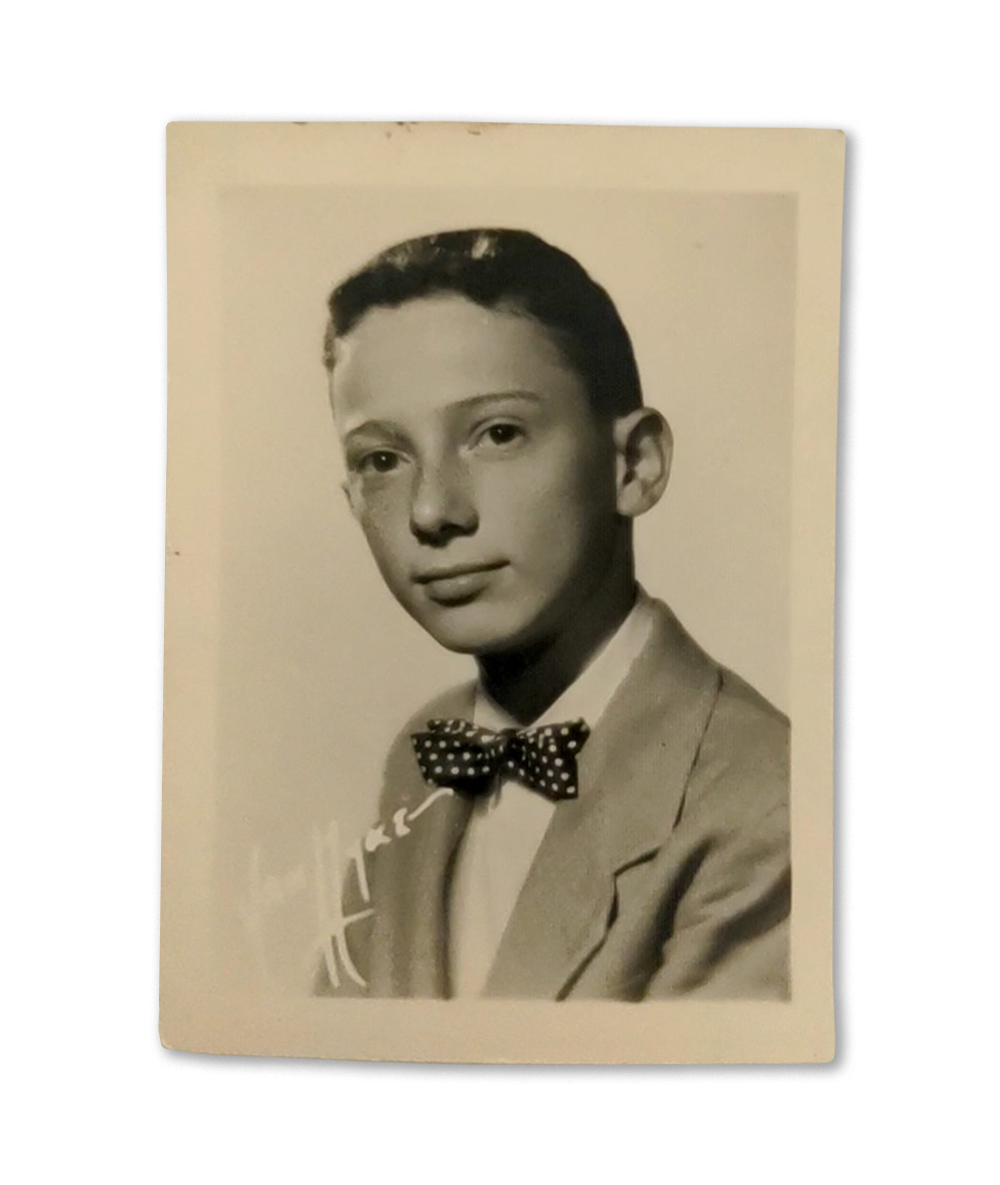

I didn’t argue. I didn’t know anything about a montage or an artist. Bailey had not brought back any books to explain these things. A few days later, I took a bus downtown to that artist’s studio, carrying my tan suit jacket in a paper bag. Bailey said I could wear blue jeans because nobody would see my lower body. Van Dyke made me sit up straight, he folded my hands, one over the other, and coaxed me into degrees of smiling.

I don’t remember how we presented that gift to my parents. Did my father take off his long-billed cap and bifocals to squint in pride? Did my grandmother finally agree that photographs were worth taking? Did my grandfather slow down enough to bask in the beauty of his grandchildren? And did anyone notice that the missing part of our montage was the eye of Mr. Sandler, who had photographed all the other significant events in our lives?

From time to time, Mr. Sandler would stop by, as close friends do. He didn’t have to announce himself or call in advance. He just parked his dark green Pontiac and rang the doorbell. And when he did, what a panic ensued. My mother went into action: “Quick! The picture!” she’d yell, and one of us would jump on the nearest chair, grab Van Dyke’s work of art and slip it behind our 16-inch Philco TV. Sometimes the gray-gold corner of the French provincial frame peeked out. If she had time, my mother threw a cleaning rag over it.

We acted as if everything was normal. We drank coffee and ate sponge cake and talked about the Jews of Dublin and Grand Rapids, about President Eisenhower and the Rosenbergs espionage trial. But we knew what we had done. “Quick! The picture!” was our admission of guilt. We had chosen art over friendship, betrayed the second best for the best.

Sixty years later, after my mother died and we were packing up her things, I spotted the montage on the floor of her living room. The frame was still intact, the glass cracked at an oblique angle all the way down. There I was, my 11-year-old head and a fragment of my tan suit visible just above Van Dyke’s slanted signature. Matkey’s head, just above mine, Bailey’s at the top: three American children, as portrayed by an artist, leaping into the middle class, face-first.

Max Apple is a short-story writer, novelist, and professor.