Invisible Man: Has the Soviet Philip Roth Found Peace in a Cemetery in Queens?

Sergei Dovlatov’s self-obsession prefigured the grim humor of post-Soviet American Jewish Lit

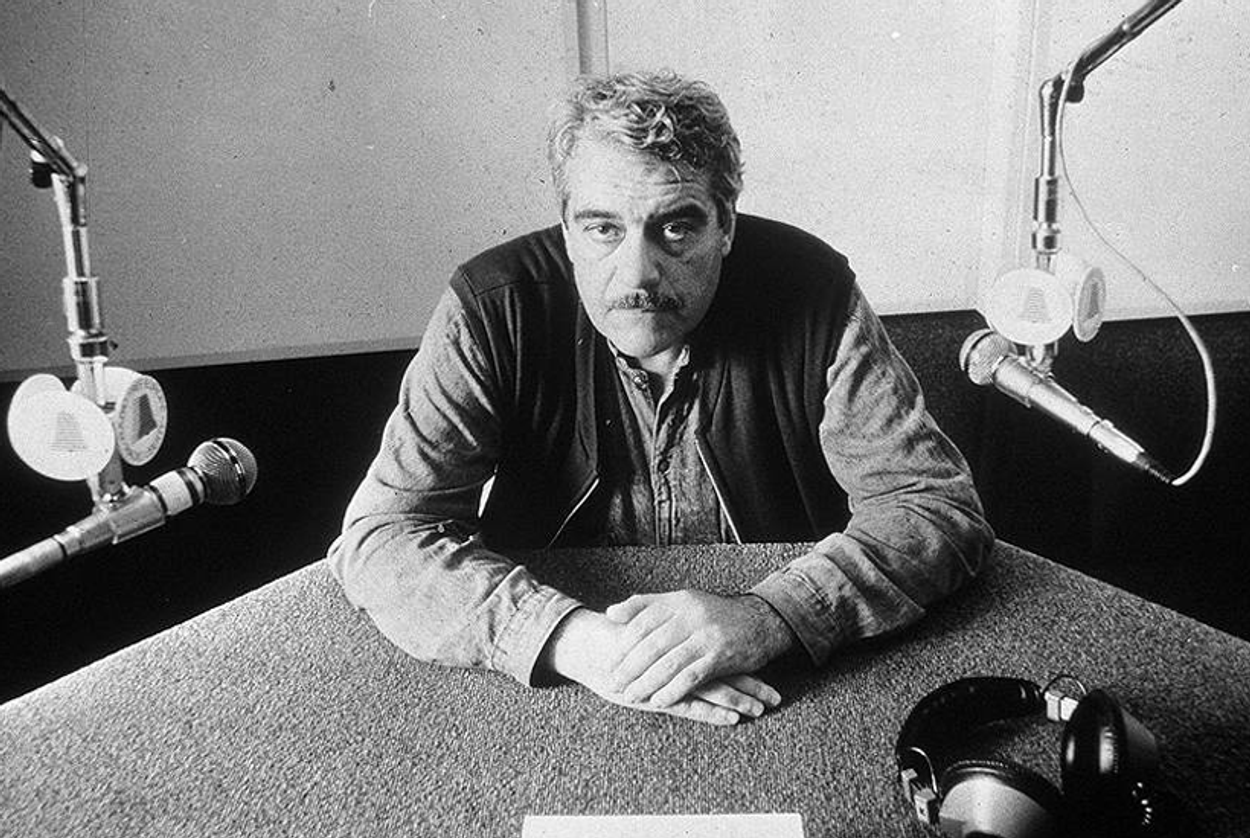

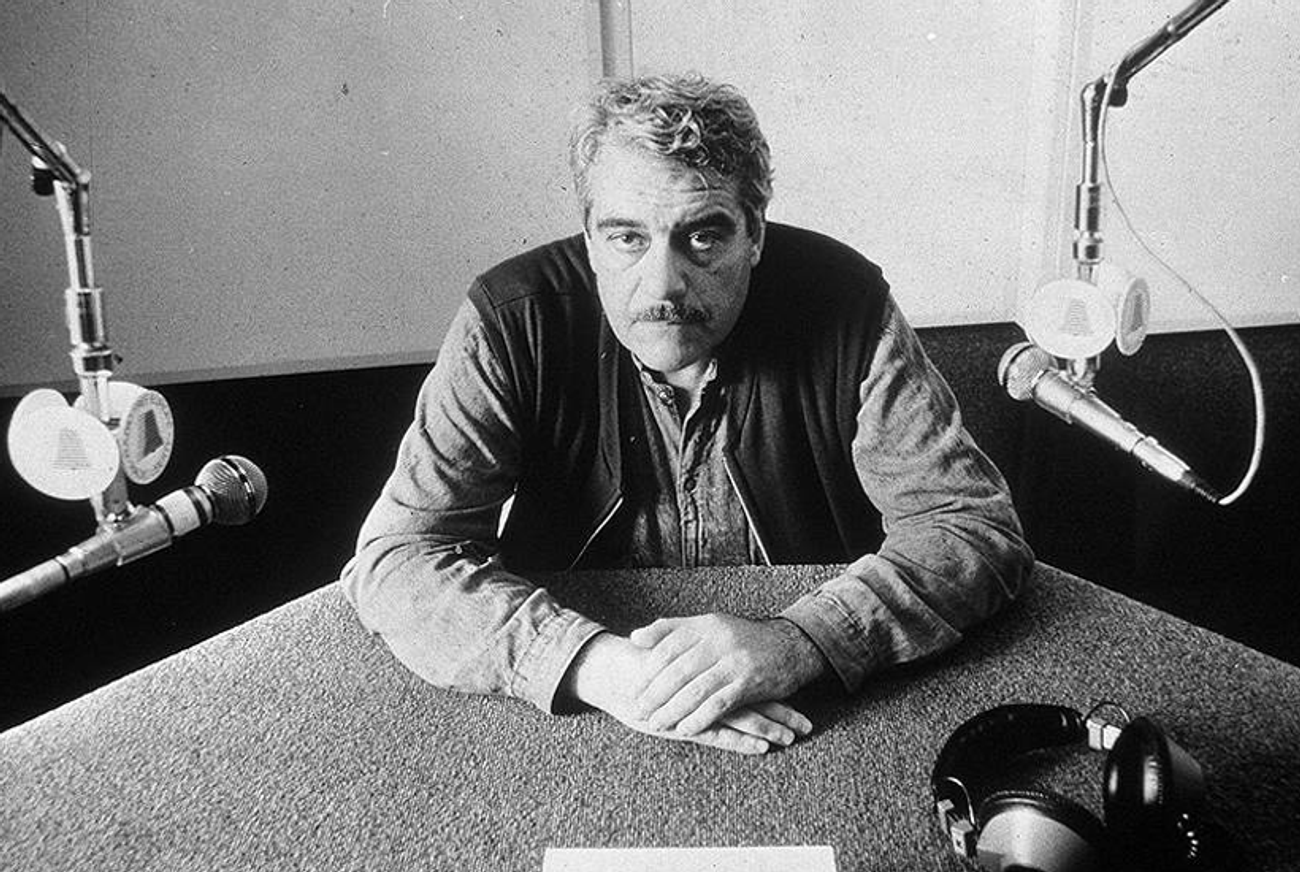

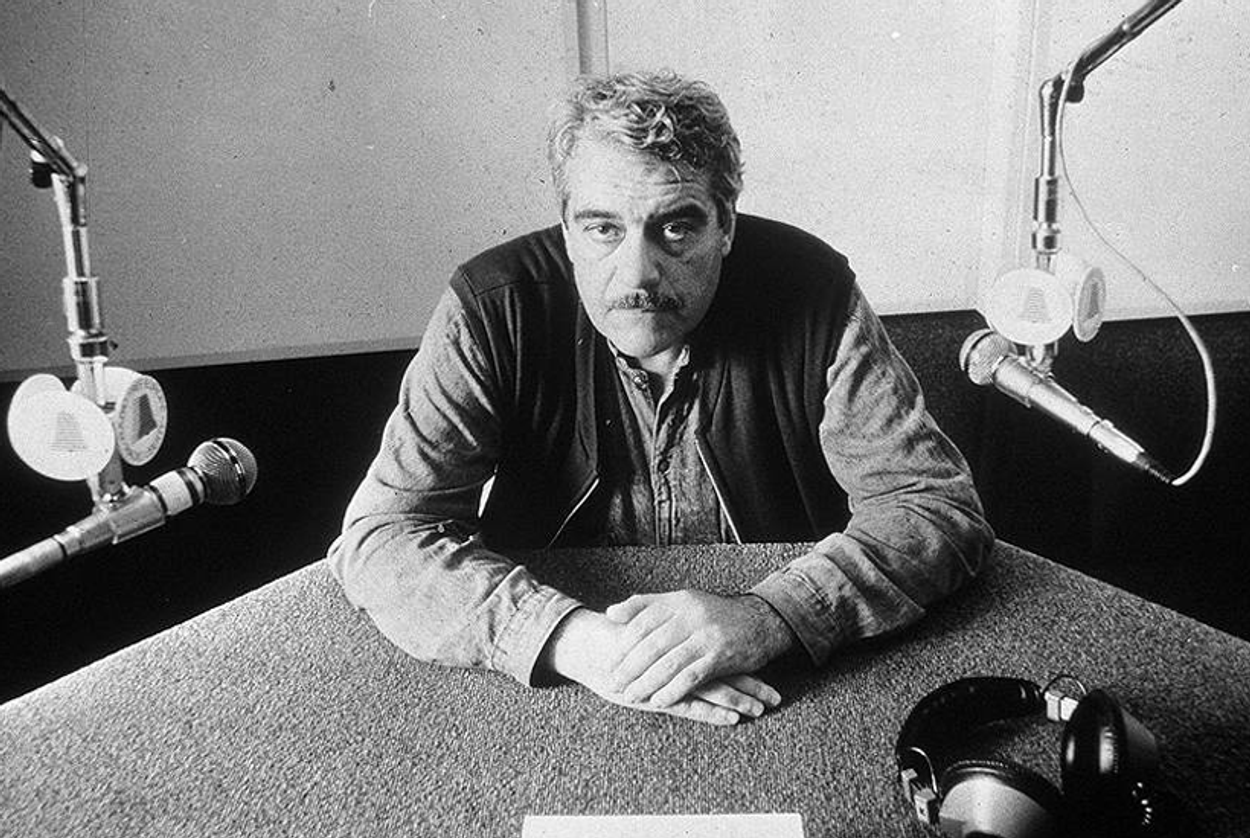

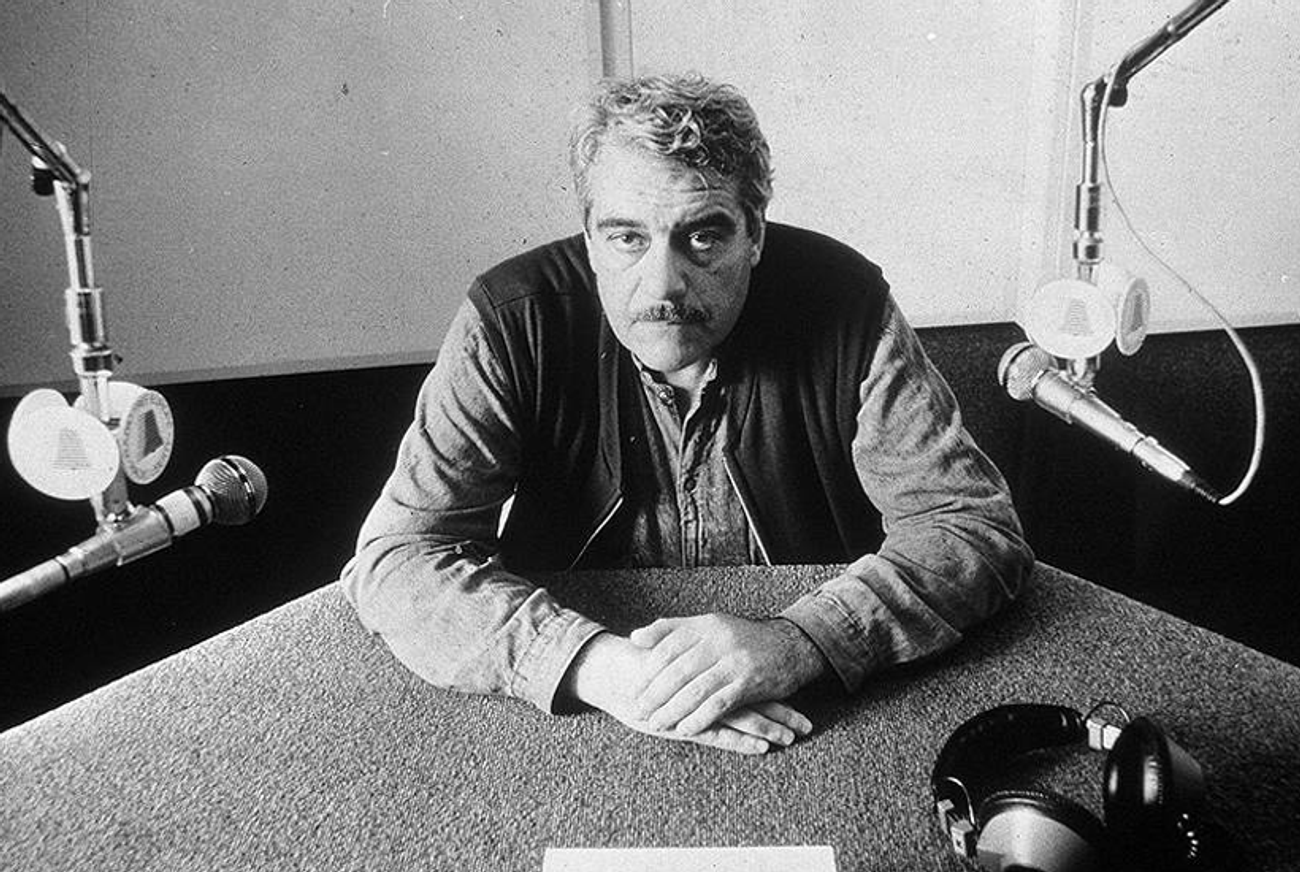

Sergei Dovlatov’s first book was originally published in the United States in 1978 and promptly led Soviet authorities to allow him to leave for the West, where he became briefly famous, edited a Jewish émigré newspaper, and died despondent, unable to write after years of productivity. Out in a new paperback edition this winter, The Invisible Book, made visible the key features of his prose: laconic style, unabashed interest in the self, and an understated and deep interest in moral life.

The Invisible Book contains, among other things, Dovlatov’s actual review of a performance in Tallinn, where he was working as a journalist, by the pianist Oscar Peterson, “the unsurpassed jazz improviser.” Dovlatov loved jazz, as practically did everyone in his cohort in Leningrad in the early 1960s. They loved it because it was American, free, and grounded in improvisation—the very antithesis of the Soviet reality around them. “It’s hard to write about jazz,” Dovlatov notes. “I could talk about Peterson’s use of diatonic and chromatic sequences and polytonal chords; I could talk about the harmonious relationship between the tonic and the sub-dominant, or I could comment on the various relationships between higher mathematics and jazz … but what for?” He could, but more important is Peterson’s “solitary, trembling, tormenting note in the silence …” The punch line comes when Peterson “solemnly” shakes Dovlatov’s hand and exclaims, “This is some kind of record! It’s the first time I’ve been written in such small type!”

The amusement that crosses into the morally ambiguous and the absurd is Dovlatov’s trademark. Yet, like jazz, it’s hard to write about Dovlatov, who insisted on being called a storyteller rather than a writer. According to his Notebooks, “A storyteller works at the level of voice and hearing. A prose writer—at the level of heart, mind and soul. A novelist—at the cosmic level. A storyteller tells about how people live. A prose writer tells about how people should live. A novelist tells about the purpose of their lives.” Walter Benjamin famously defines the storyteller in similar deceptively simple terms, “The storyteller takes what he tells from experience—his own or that reported by others. And he in turn makes it the experience of those who are listening to his tale.”

It’s remarkable that most of Dovlatov’s works have been translated into English while a good deal of 20th century Russian literature remains still unavailable in translation. The most immediate reason is his biography: He became a published writer only after coming to the United States in 1979. Although he couldn’t write in any other language but Russian, translation into English began soon, with publications in the prestigious presses and The New Yorker. Dovlatov’s passion for American literature, music, and cinema was overwhelming; he mused that translations of American literature healed Russian language in the Soviet “jungle.” Yet his debates with and enormous indebtedness to Russian literature never ended—nor did his preoccupation with everything Soviet. Notwithstanding his enormous posthumous fame in Russia, Dovlatov is best seen as an American artist, the Russian-language equivalent of the Yiddish-speaker I.B. Singer.

Dovlatov is a “boiler-down.” This is how Bill Maher recently described Jerry Seinfeld and his series Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. Aesthetically Dovlatov is thoroughly Seinfeldian: His obsession is achieving, maintaining, and replicating the terse precision of style, which boils down experience to the perfectly wrought phrase. Seinfeld’s comedy dwells on the ordinary without compunction, fully aware that anything “normal” is in fact an oddity, or even an absurdity, in contrast to George Costanza—Dovlatov’s true spiritual heir—whose experience of the absurdities of life is as funny, but also pitiful, self-damaging and morally fraught. In Seinfeld’s season 9, Jerry, who has become kind and sensitive, asks George to tell him about his deepest secrets and worries. After George confesses all of them, Jerry is terrified and jolted back into his cheery indifferent self. George, like Dovlatov, carries the absurd within, while Jerry is protected against it.

Like the characters on Seinfeld, Dovlatov’s true one and only obsession is himself, be he called Dovlatov or not. His constant and consistent blending of what actually took place and what he made up destabilizes life and text. Life—“auto-biography”—stops being a mere pretext for literature and usurps imagination rather than vice versa in a way that also recalls Philip Roth, who approaches him in extreme self-absorption. As Jacques Berlinerblau put it, “Philip Roth writes novels about novelists who uncannily resemble Philip Roth. Philip Roth writes novels about novelists who are ‘Philip Roth’… Then, for kicks, Philip Roth proceeds to correct those clodhoppers who surmise he may be writing about Philip Roth.” Dovlatov creates a similar maddening circle and asks us to believe that it is predicated on internal order—an antidote against the absurdity of the chaos of life.

To survive in this life for Dovlatov is to be morally tainted.

Yet, like Roth, Dovlatov is a moral thinker. The origin of Dovlatov’s moral philosophy is in The Zone(1982), the bulk of which was written in the USSR. Based on Dovlatov’s army service as a guard in a prison camp, it blends the grotesque and nightmarish stories about the prisoners with the author’s letters to his Russian American publisher. In one of the letters, Dovlatov lays out his take on human nature, “[A]ny categorical moral position seems ridiculous to me. Man is to man … a tabula rasa … anything you please, depending on the conjunction of circumstances. For this reason, may God give us steadfastness and courage and … circumstances of time and place that are disposed to the good.” This sentiment is the major leitmotif of Dovlatov’s novels and stories and echoes the Talmudic rabbis’ exceptionally sober view of humanity. The rabbis also insist on the neutrality of human soul, which contains an equal amount of the good impulse—yetzer ha tov—and the evil inclination—yetzer ha ra. Thus, each one of us has to decide which component will dominate within.

Dovlatov is not a historical relativist who thinks that America is the same as the Soviet Union. For him, the penal camp equals the Soviet system and mindset; the official and everyday Soviet realms outside the “zone” are similarly repulsive and permeable. In a letter to his father written from the camp, he states, “We live in a bad time in a bad country, where lies and insincerity have become a natural instinct just like hunger and love.” Yet precisely because human behavior is the same everywhere, solely contingent on circumstances, chaos of absurd pettiness and randomness persists everywhere as well. Western freedom cannot eliminate this condition. The interchangeability of criminals and guards, which Dovlatov claims to have discovered in the “zone,” is in fact his lesson from American film noir. In the Invisible Book, he writes, “The police and the thieves have an extraordinary resemblance to each other.” Evocative of the great camp literature by Solzhenitsyn, Shalamov, and Primo Levi, this is a verbatim restatement of noir’s main point: “We all work for our vice,” as the psychiatrist says in The Asphalt Jungle. To survive in this life for Dovlatov is to be morally tainted.

***

Since Dovlatov’s life is inseparable from his art, it is impossible to divorce his life story from the philosophy of his books and their plots. One derives from the other. His was a life of paradoxes: a person who from the very beginning deeply resented anything Soviet, political, social, and cultural, was absolutely determined to become a published Soviet author. When he finally became a successful writer in the United States, a country he admired both as an idea and often a reality, he grew increasingly despondent, hitting the wall of renewed alcoholism and writer’s block in his last year. Nothing changes and nothing’s changed is the quiet motto of Dovlatov’s life.

Born in 1939, Dovlatov belonged to the generation of Joseph Brodsky, which “approached the idea of individualism and the principle of the autonomy of human life more seriously than it’s been approached anywhere and by anyone prior” (Brodsky). While Brodsky felt that this idea and principle are completely incompatible with a professional literary career in the USSR, Dovlatov persisted in his attempts to get into print. His best books—The Invisible Book, The Compromise, Pushkin Hills, and The Suitcase—unveil this grotesque comedy of failure after failure and compromises, such as, for instance, working as a journalist, stuck in between. In the Invisible Book, which recounts the near publication of the collection of his stories—the KGB destroyed the galleys of the book—one editor tells Dovlatov, “A writer should be published, but not, of course, to the detriment of his talent. There’s a tiny crevice separating conscience from baseness. One has to penetrate that crevice.” Dovlatov realizes that this “crevice” contains a wolf-trap where he and his characters often get caught. This “crevice” between good and evil is the encapsulation of his moral philosophy. How to endure it with the least amount of moral taintedness is the question of Dovlatov the man and Dovlatov the writer.

Pushkin Hills, recently translated by Dovlatov’s daughter, offers the best insight into this predicament. Written a year before he left Russia, it is ironically the story of resistance to immigration, which provided the only real practical exit out of the Soviet hell. Describing his work as a tour-guide in the “Pushkin sanctuary”—Pushkin’s estate and the place of his burial—it places the author’s troubles against those of Russia’s greatest poet. In a letter to his Russian publisher in America, regarding the novel, Dovlatov writes, “I would like to portray a writer in the Pushkin sanctuary, whose problems are similar to Pushkin’s: money, wife, art, and power.” Dovlatov is repulsed by the sanctimoniousness of the Pushkin cult—he’d be equally disturbed by the cult around his own name now—and tries to figure out what it meant for Pushkin to be a struggling writer rather than an icon. He thinks of Pushkin who accepted the limitations of human nature and Russian history and, rather than wallowing in tragedy or preaching moral absolutism, treated any human situation with the equal amount of fascination and compassion.

Dovlatov wants to achieve this equilibrium aesthetically—Pushkin’s laconic non-judgmental prose is for him the perfection—morally, and existentially. Yet the last two prove to be hard in the presence of his own self-doubt and reality’s overwhelming insanity, lies, and cruelty. The “crevice” becomes once more the wolf-trap, leading to a permanent friction with life. Paradoxically this is why in Pushkin Hills the narrator is terrified of immigration, demanded by his wife. Masking his indecision as the inability to leave his language, he admits to himself, “all my rationalizations were lies. It wasn’t about that. I simply could not make this decision. … After all it would be like being reborn.” What if life in America would actually be more conducive to happiness, forcing the writer to be “reborn” as a man with a distinctly different view of the world? Dovlatov’s simultaneous American success and failure touch directly on his Jewish problem.

***

Dovlatov was born to a Jewish father and an Armenian mother and so could leave the Soviet Union as a Jew, along with the hundreds of thousands of others who did so from the mid-1970s to the late ’80s. Jewish characters populate most of his novels and stories. He shows that to be a Jew in the Soviet context is to be a constant thorn in the regime’s side. Dovlatov’s attitude toward his Jewishness is twofold: On the one hand, he wants to normalize the Jewish condition. On the other, since the first proves to be impossible due to ubiquitous anti-Semitism, he imagines situations that would allow the Jew to become heroic. In Ours, the story of his family, Dovlatov creates an outlandish Jewish genealogy. His great-grandfather Moses is a peasant born in the Far East rather than in the shtetl. His son Isaac is a Jewish renegade, who despises the Soviet power and physically repels any expression of anti-Semitism. He is a mixture of the biblical Samson, Isaac Babel’s Odessan gangsters, and classic Zionist spirit. “I have a few photographs of Grandpa,”—writes Dovlatov—“When my grandchildren leaf through the family album, it won’t be hard for them to mistake us for one another.”

Not everyone can be the epic grandpa Isaac. It is the ordinary Jews who were on Dovlatov’s mind in America; hence the novel A Foreign Woman and the newspaper The New American. Dovlatov was the major force behind the weekly and its editor-in-chief, sticking with it for two years. The new periodical, he stipulated, was Russian, American, and Jewish—Jewish not because of ideology or religion, but because most of its readers were Jews. Thus, the normalization of the Jewish condition, which could not happen in the Soviet Union, was given a chance in the free America. The result was a mixed bag: Continuously under pressure by readers and sponsors to be more Jewish and more “correctly” Jewish, Dovlatov understood that the Jewish factor was no longer the way out of the norm, but the way in. The conformism and self-censorship he left in the Soviet Union reemerged in a new guise in America. At the same time the newspaper was immensely popular. Many of Dovlatov’s editorial columns discussed Jewish topics, such as Israel, in touching and genuine terms. Through The New American Dovlatov was coming to terms with the unexpected “conjunction of circumstances”: A bit of absurdity and compromise did not preclude the acceptance of professional success.

A Foreign Woman, Dovlatov’s Fiddler on the Roof, takes place in the Jewish Russian area of Queens, where he lived with his family and that now features a street in his name. The novel is infused with this newly found spirit of the gentle embrace of and compassion toward life’s foibles. One of its characters, Fima Druker, becomes a publisher in immigration—“Druker” means “printer” in Yiddish. He publishes only one book: German Jewish writer Leon Feuchtwanger’s novel The Jew Suss (1925). The problem is that there’s a typo: FeuchtwaNger turns into FeuchtwaGner.

By flipping the iconic Jewish writer into the iconic anti-Semite, Dolvatov insists that the Jewish condition cannot be normalized: Hatred of the Jew is inescapable. For a great majority of post-World War II Soviet Jews, Feuchtwanger’s historical novels amounted to a Scripture. They learned from them about Jewish history and how not to be ashamed. In the novel, Feuchtwanger makes Suss, a famous court Jew whose life would inspire the infamous Nazi film, into the paragon of teshuvah: Imprisoned and hounded, Suss returns to his people and God. Comical and disturbing, problematic and emblematic of Dovlatov’s philosophy of the absurd, Druker’s typo gnaws at the warm and fuzzy texture of A Foreign Woman.

According to his letters, A Foreign Woman was the only book Dovlatov disliked writing. Despite his rebirth through immigration, Dovlatov the philosopher could not abide life’s “normalcy.” “Success” in the West opened a familiar “crevice between conscience and baseness.” His novel The Branch, unavailable in English, is about the American crevices and compromises, such as working at the Radio Liberty in New York: Pushkinian lightness and balance again seemed like a remote possibility. In the 1989 confessional letter to Igor Efimov, who published most of his books in the original in the United States, he wrote, “[A]ll my life I lived naturally in the atmosphere of failure, which was confirmed at the end by the concrete circumstances—disillusionment in my creative abilities, problems with health and a pretty grim remainder of the life ahead. … By nature I am a distorter, no matter how hard I tried to present this vice as an artistic activity, it is the truth.” His inability to deal with Jewishness exacerbated these feelings. In another letter to Efimov, Dovlatov admits, “Perhaps it is anti-Semitism, but I am not ready to be around so many full-bloodied Jews, none of whom doubt even for a second that they’re perfect.”

Dovlatov died at 49 in 1990. Soon thereafter his books started to come out in Russia. Perhaps the wisdom and serenity, which mark Philip Roth’s last novels, would have come with age. Yet it is precisely Dovlatov’s inability to be sanguine about life’s absurdity that makes him such a terribly relevant and fascinating writer. Buried among Russian Jews at the Mount Hebron cemetery in Queens, did he acquire there the quiet normalcy he so desperately desired?

Marat Grinberg teaches literature and film at Reed College. His forthcoming book is The Soviet Jewish Bookshelf: Culture and Identity Between the Lines (Brandeis University Press).